Benjamin Franklin and the Kite Experiment

We all know the story of Franklin’s famous kite-in-a-thunderstorm experiment. But is it the true story?

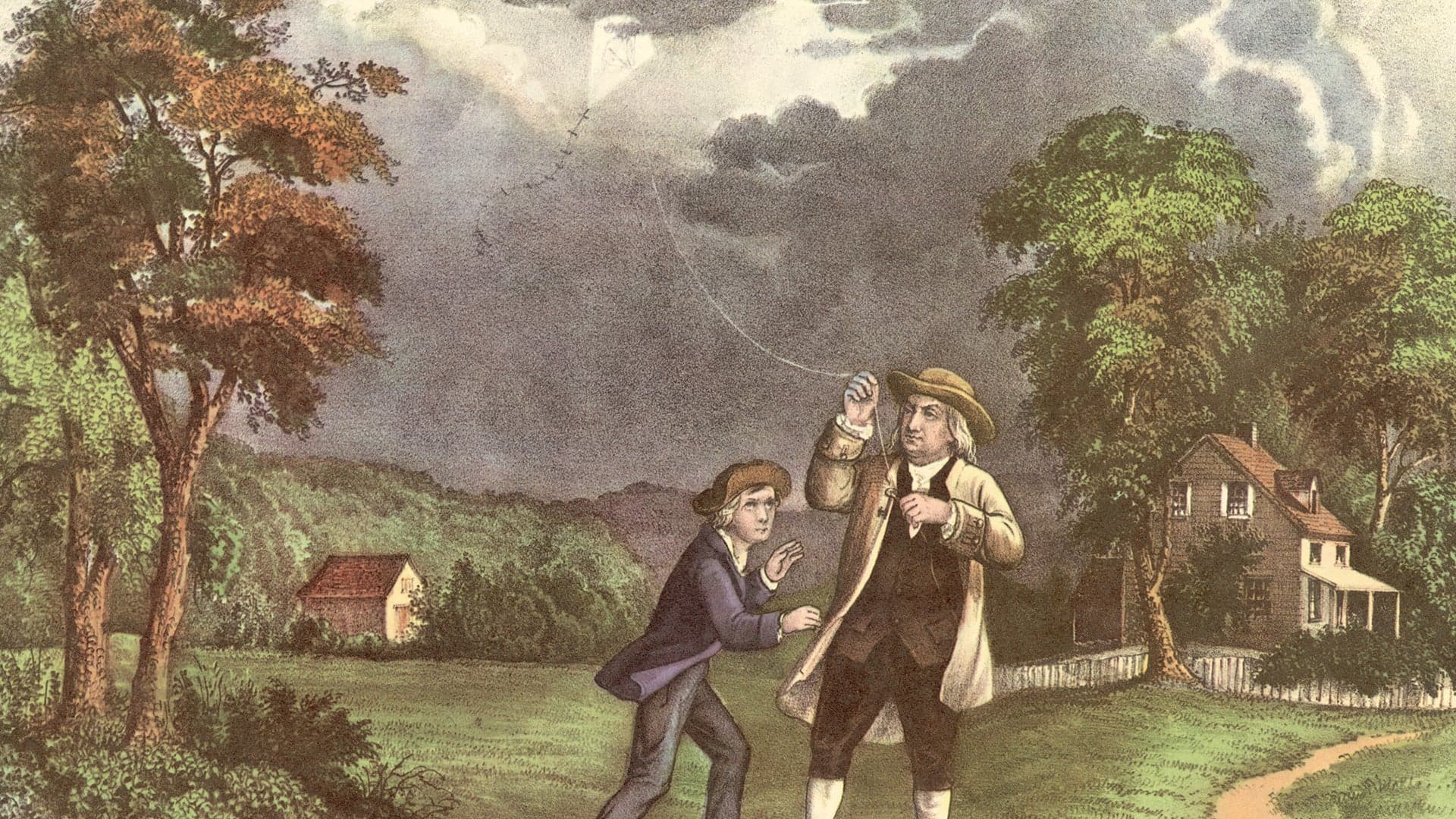

On a June afternoon in 1752, the sky began to darken over the city of Philadelphia. As rain began to fall and lightning threatened, most of the city’s citizens surely hurried inside. But not Benjamin Franklin. He decided it was the perfect time to go fly a kite.

Franklin had been waiting for an opportunity like this. He wanted to demonstrate the electrical nature of lightning, and to do so, he needed a thunderstorm.

He had his materials at the ready: a simple kite made with a large silk handkerchief, a hemp string, and a silk string. He also had a house key, a Leyden jar (a device that could store an electrical charge for later use), and a sharp length of wire. His son William assisted him.

Franklin had originally planned to conduct the experiment atop a Philadelphia church spire, according to his contemporary, British scientist Joseph Priestley (who, incidentally, is credited with discovering oxygen), but he changed his plans when he realized he could achieve the same goal by using a kite.

So Franklin and his son “took the opportunity of the first approaching thunder storm to take a walk into a field,” Priestley wrote in his account. “To demonstrate, in the completest manner possible, the sameness of the electric fluid with the matter of lightning, Dr. Franklin, astonishing as it must have appeared, contrived actually to bring lightning from the heavens, by means of an electrical kite, which he raised when a storm of thunder was perceived to be coming on.”

Despite a common misconception, Benjamin Franklin did not discover electricity during this experiment—or at all, for that matter. Electrical forces had been recognized for more than a thousand years, and scientists had worked extensively with static electricity. Franklin’s experiment demonstrated the connection between lightning and electricity.

The Experiment To dispel another myth, Franklin’s kite was not struck by lightning. If it had been, he probably would have been electrocuted, experts say. Instead, the kite picked up the ambient electrical charge from the storm.

Here’s how the experiment worked: Franklin constructed a simple kite and attached a wire to the top of it to act as a lightning rod. To the bottom of the kite he attached a hemp string, and to that he attached a silk string. Why both? The hemp, wetted by the rain, would conduct an electrical charge quickly. The silk string, kept dry as it was held by Franklin in the doorway of a shed, wouldn’t.

The last piece of the puzzle was the metal key. Franklin attached it to the hemp string, and with his son’s help, got the kite aloft. Then they waited. Just as he was beginning to despair, Priestley wrote, Franklin noticed loose threads of the hemp string standing erect, “just as if they had been suspended on a common conductor.”

Franklin moved his finger near the key, and as the negative charges in the metal piece were attracted to the positive charges in his hand, he felt a spark.

“Struck with this promising appearance, he immediately presented his knucle [sic] to the key, and (let the reader judge of the exquisite pleasure he must have felt at that moment) the discovery was complete. He perceived a very evident electric spark,” Priestley wrote.

Using the Leyden jar, Franklin “collected electric fire very copiously,” Priestley recounted. That “electric fire”—or electricity—could then be discharged at a later time.

Franklin’s own description of the event appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette on October 19, 1752. In it he gave instructions for re-creating the experiment, finishing with:

As soon as any of the Thunder Clouds come over the Kite, the pointed Wire will draw the Electric Fire from them, and the Kite, with all the Twine, will be electrified, and the loose Filaments of the Twine will stand out every Way, and be attracted by an approaching Finger. And when the Rain has wet the Kite and Twine, so that it can conduct the Electric Fire freely, you will find it stream out plentifully from the Key on the Approach of your Knuckle. At this Key the Phial may be charg’d; and from Electric Fire thus obtain’d, Spirits may be kindled, and all the other Electric Experiments be perform’d, which are usually done by the Help of a rubbed Glass Globe or Tube; and thereby the Sameness of the Electric Matter with that of Lightning compleatly demonstrated.

Franklin wasn’t the first to demonstrate the electrical nature of lightning. A month earlier it was successfully done by Thomas-François Dalibard in northern France. And a year after Franklin’s kite experiment, Baltic physicist Georg Wilhelm Richmann attempted a similar trial but was killed when he was struck by ball lightning (a rare weather phenomenon).

After his successful demonstration, Franklin continued his work with electricity, going on to perfect his lightning rod invention. In 1753, he received the prestigious Copley Medal from the Royal Society, in recognition of his “curious experiments and observations on electricity.”

By Nancy Gupton. Published June 12, 2017.

- Buy Tickets

- Accessibility

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Daily Schedule

- Getting Here

- Where to Eat & Stay

- All Exhibits & Experiences

- Wondrous Space

- Body Odyssey

- Hamilton Collections Gallery

- Science After Hours

- Events Calendar

- Staff Scientists

- Benjamin Franklin Resources

- Scientific Journals of The Franklin Institute

- Professional Development

- The Current: Blog

- About Awards

- Ceremony & Dinner

- Sponsorship

- The Class of 2024

- Call for Nominations

- Committee on Science & The Arts

- Next Generation Science Standards

- Title I Schools

- Neuroscience & Society Curriculum

- STEM Scholars

- GSK Science in the Summer™

- Missions2Mars Program

- Children's Vaccine Education Program

- Franklin @ Home

- The Curious Cosmos with Derrick Pitts Podcast

- So Curious! Podcast

- A Practical Guide to the Cosmos

- Archives & Oddities

- Ingenious: The Evolution of Innovation

- The Road to 2050

- Science Stories

- Spark of Science

- That's B.S. (Bad Science)

- Group Visits

- Plan an Event

Did Benjamin Franklin really discover electricity with a kite and key?

Did the founding father really discover electricity?

On a dark, stormy summer night in 1752, Benjamin Franklin flew a kite with a key attached to the string waiting in anticipation for lightning to strike. The dramatic bolt would harken the discovery of electricity (or as Franklin called it "electrical fire") … or so the story goes.

But is there any truth to this tale? Did Franklin really discover electricity by getting zapped by a lightning bolt during this experiment?

Though most people know Benjamin Franklin — an American founding father, legendary statesman and the face of the U.S. $100 bill — for his political contributions, Franklin was well known in his time as a scientist and an inventor: a true polymath. He was a member of several scientific societies and was a founding member of the American Philosophical Society. As a result, he stayed informed on the most pressing scientific questions that occupied learned people of his time, one of which was the nature of lightning.

As for the kite-and-key experiment, most people are aware of the version in which the metal key acted as a lightning rod, and Franklin subsequently "discovered" electricity when lightning struck his kite. However, several details about this experiment are unknown, including when and where it happened. Some historians even doubt that it took place.

Related: Did Benjamin Franklin really want the turkey to be the US national bird?

For starters, it's a common myth that Franklin discovered electricity. Electricity had already been discovered and used for centuries before Franklin's experiment. Franklin lived from 1709 to 1790, and during his time, electricity was understood as the interaction between two different fluids , which Franklin later referred to as "plus" and "minus." According to French chemist Charles François de Cisternay du Fay, materials that possessed the same type of fluid would repel, while opposite fluids attracted one another. We now understand that these "fluids" are electrical charges generated by atoms. Atoms are made up of negatively charged electrons orbiting a positively charged nucleus (made up of protons and neutrons).

It was unknown prior to Franklin's experiment whether lightning was electrical in nature, though some scientists, including Franklin, had speculated just that . Page Talbott, author and editor of " Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World " (Yale University Press, 2005) and the former president and CEO of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, said that Franklin was particularly interested in this question because lightning strikes had caused disastrous fires in cities and towns where houses were made of wood, which many homes in the U.S. were at the time. "By attaching a key to the string of a kite, thus creating a conductor for the electrical charge , he was demonstrating that a pointed metal object placed at a high point on a building — connected to a conductor that would carry the electricity away from the building and into the ground — could make a huge difference to the long-term safety of the inhabitants," Talbott told Live Science in an email. In other words, by creating a lightning rod, Franklin was helping to protect wooden homes and buildings from being directly struck by lightning.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lightning rods are metal rods placed at the top of structures, connected to the ground with a wire. If lightning strikes the building, it will likely strike the electrically conductive rod instead of the building itself and safely run through the wire to the ground.

Here's how the experiment worked; standing in a shed, Franklin flew a kite, made of a simple silk handkerchief stretched across a cross made of two cedar strips, during a lightning storm. The tail of the kite was made of two materials — the upper end attached to the kite was made of hemp string and attached to a small metal key, while the lower end, held by Franklin, was made of silk. The hemp would get soaked by the rain and conduct electrical charge, while the silk string would remain dry because it is held under cover.

As Franklin observed his flying kite, he saw that the hemp strands stood on end as they began to accumulate electrical charge from the ambient air. When he placed his finger near the metal key, he reportedly felt a sharp spark as the negative charges that had accumulated on the key were attracted to the positive charges in his hand.

A few publications at the time reported on the experiment. "[Franklin] published a statement about the experiment in the Pennsylvania Gazette , the newspaper he published, on October 19, 1752," Talbott said. He then sent the text of this statement to a patron of the American Philosophical Society named Louis Collinson; Franklin had spent the last few years communicating his theories and proposing his experiments concerning lightning to him.

Franklin referred to the experiment in his autobiography, and other colleagues in Europe wrote about it as well, Talbott said. Notably, the experiment appeared in the 1767 book " History and Present Status of Electricity " by Joseph Priestley, an English chemist. Priestley heard about the kite-and-key experiment from Franklin himself around 15 years after the fact, and in his book, he wrote that it occurred during June 1752. However, exactly when the experiment came to Franklin and when he did it is a matter of debate.

There are some historians who doubt whether Franklin actually did the experiment himself, or merely outlined its possibility. In his book " Bolt of Fate: Benjamin Franklin and His Electric Kite Hoax " (PublicAffairs, 2003), author Tom Tucker stated that Franklin wanted to thwart William Watson, a member of the Royal Society of London and a preeminent electrical experimenter. Watson had sabotaged the publication of some of Franklin's previous reports and had ridiculed his experiments in the Royal Society, Tucker wrote. Could Franklin have felt pressured to invent the kite story to get back at Watson?

— What happened to the 'vanished' colonists at Roanoke?

— Did Elizabeth Taylor really have violet eyes?

— How far away is lightning?

Tucker also noted that Franklin's description of his experiment in the Pennsylvania Gazette was phrased in the future conditional tense: "As soon as any of the Thunder Clouds come over the Kite, the pointed Wire will draw the Electric Fire from them..." Franklin could have simply been saying that the experiment could, in theory, be performed. Given that his statement has a few missing details — Franklin didn't list a date, time or location, for example — it's possible that the American diplomat did not perform the experiment himself.

However, some historians remain unconvinced that the experiment wasn't carried out, pointing to Franklin's great respect for scientific pursuits . Franklin experts, such as the late American critic and biographer Carl Van Doren, also point to the fact that Priestley specified the month in which Franklin performed his experiment, suggesting that Franklin must have given him precise details directly.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jacklin Kwan is a freelance journalist based in the United Kingdom who primarily covers science and technology stories. She graduated with a master's degree in physics from the University of Manchester, and received a Gold-Standard NCTJ diploma in Multimedia Journalism in 2021. Jacklin has written for Wired UK, Current Affairs and Science for the People.

24 brain networks kick in when you watch movies, study finds

Content funding on Live Science

Canada wants your help to name its 1st moon rover

Most Popular

- 2 Meet 'Chameleon' – an AI model that can protect you from facial recognition thanks to a sophisticated digital mask

- 3 Space photo of the week: James Webb telescope spots a secret star factory in the Sombrero Galaxy

- 4 Can you get high from poppy seeds?

- 5 Mass extinctions make life 'bounce back stronger,' controversial study suggests

- Short Biography

- Who was Ben Franklin?

- Why is Benjamin Franklin on the $100 bill?

- Google Plus

Kite Experiment

Flying a kite in a storm was perhaps Benjamin Franklin’s most famous experiment that led to the invention of the lightning rod and the understanding of positive and negative charges. The connection between electricity and lightning was known but not fully understood. By conducting the kite experiment Franklin proved that lighting was an electrical discharge and realized that it can be charged over a conductor into the ground providing a safe alternative path and eliminating the risk of deadly fires.

Erecting iron rods

Iron rod experiment conducted by French scientist Thomas François Dalibard.

Franklin hypothesized that lightning was an electrical discharge. Before he thought of conducting his experiment by flying a kite, he proposed erecting iron rods into storm clouds to attract electricity from them. He also suggested that the tips of the rods should be pointed instead rounded so that they could draw electrical fire out of a cloud silently. Franklin speculated about its usefulness for several years as he was unable to perform his experiment since he thought it had to be conducted from a higher ground. Philadelphia has a flat geography and at the time there were no tall structures, he was anxiously waiting for the construction of Christ Church that was being built on a steeple to conduct his experiment.

Franklin wrote his proposal for the iron rod experiment in a letter to Peter Collison who was a member of the Royal Society of London. Collison presented Franklin’s hypothesis to the Society who ridiculed and laughed at his idea failing to recognize its significance. A year later when the French translation was published it attracted the interest of French scientists Delor and Dalibard, who separately and successfully conducted Franklin’s experiment calling it the “Philadelphia experiment”.

Franklin was recognized by the Royal Society of London and in scientific circles all over Europe, becoming the most famous American in Europe.

Flying a kite

Franklin kept himself and the end of the string dry to protect himself from being electroshocked.

Franklin had not heard of the success of his experiment in Europe before he conducted the same experiment with a kite. One day in June 1752, it occurred to him that he could test his hypothesis by flying a kite instead of waiting for the church to be built. With the help of his son William he built the body of the kite with two crossed strips of cedar wood and a silk handkerchief instead of paper as it would not tear with wind and rain. They attached a foot long sharp and pointed wire to the top of the kite as a conductor and at the bottom end of the string where it is held they attached a silk ribbon and a metal key. A metal wire connected the key to the Leyden Jar.

Franklin kept dry by retreating into a barn; the end of the string was also kept dry to insulate himself. When the stormed passed over his kite the conductor drew electricity into his kite. The kite was not struck by lightning but the conductor drew negative charges from a charged cloud to the kite, string, metal key and Leyden jar. It appears that he knew enough about grounding to protect himself from being electroshocked. When he moved his hand near the key he received a shock because the negative charge attracted the positive charge in his body.

This is the description of the electric kite experiment in Franklin’s own words from the Pennsylvania Gazette dated October 19, 1752.

As frequent Mention is made in the News Papers from Europe, of the Success of the Philadelphia Experiment for drawing the Electric Fire from Clouds by Means of pointed Rods of Iron erected on high Buildings, &c. it may be agreeable to the Curious to be inform’d, that the same Experiment has succeeded in Philadelphia, tho’ made in a different and more easy Manner, which any one may try, as follows.

Make a small Cross of two light Strips of Cedar, the Arms so long as to reach to the four Corners of a large thin Silk Handkerchief when extended; tie the Corners of the Handkerchief to the Extremities of the Cross, so you have the Body of a Kite; which being properly accommodated with a Tail, Loop and String, will rise in the Air, like those made of Paper; but this being of Silk is fitter to bear the Wet and Wind of a Thunder Gust without tearing. To the Top of the upright Stick of the Cross is to be fixed a very sharp pointed Wire, rising a Foot or more above the Wood. To the End of the Twine, next the Hand, is to be tied a silk Ribbon, and where the Twine and the silk join, a Key may be fastened. This Kite is to be raised when a Thunder Gust appears to be coming on, and the Person who holds the String must stand within a Door, or Window, or under some Cover, so that the Silk Ribbon may not be wet; and Care must be taken that the Twine does not touch the Frame of the Door or Window. As soon as any of the Thunder Clouds come over the Kite, the pointed Wire will draw the Electric Fire from them, and the Kite, with all the Twine, will be electrified, and the loose Filaments of the Twine will stand out every Way, and be attracted by an approaching Finger. And when the Rain has wet the Kite and Twine, so that it can conduct the Electric Fire freely, you will find it stream out plentifully from the Key on the Approach of your Knuckle. At this Key the Phial may be charg’d; and from Electric Fire thus obtain’d, Spirits may be kindled, and all the other Electric Experiments be perform’d, which are usually done by the Help of a rubbed Glass Globe or Tube; and thereby the Sameness of the Electric Matter with that of Lightning compleatly demonstrated.

In 1753 Franklin published an article in Poor Richard’s Almanac describing how to secure houses from lightning.

It has pleased God and his goodness mankind, at length to discover to them the means of securing their habitations and other buildings from mischief by thunder and lightning. The method is this: Provide a simall iron rod but of such a length that one end being three or four deet in the moist ground, the other may be six or eight feet above the highest part of the building. To the upper end of the rod fasten about a foot of brass wire, the size of a common knitting needle, sharpened to a fine point; the rod may be secured to the house by a few small staples. If the house or barn be ling, there may be a rod and point at each end, and a middling wire along the ridge from one to the other. A house thus furnished will not be damaged by lightning, it being attracted by the points and passing thro the metal into the ground without hurting anything.

You may also like

Experiments with electricity, inventions and improvements.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : June 10

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Benjamin Franklin flies kite during thunderstorm

In the summer of 1752—possibly on the 10th of June— Benjamin Franklin flies a kite during a thunderstorm to collect ambient electrical charge in a Leyden jar, enabling him to demonstrate the connection between lightning and electricity. (Scholars debate the June 10 date , but agree it likely happened sometime in June of that year.) It is one of his most famous—and mythologized—experiments.

Franklin became interested in electricity in the mid-1740s, a time when much was still unknown on the topic, and spent almost a decade conducting electrical experiments. He coined a number of terms used today, including battery, conductor and electrician. He also invented the lightning rod, used to protect buildings and ships.

Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, to a candle and soap maker named Josiah Franklin, who fathered 17 children, and his wife Abiah Folger. Franklin’s formal education ended at age 10 and he went to work as an apprentice to his brother James, a printer. In 1723, following a dispute with his brother, Franklin left Boston and ended up in Philadelphia, where he found work as a printer. Following a brief stint as a printer in London, Franklin returned to Philadelphia and became a successful businessman, whose publishing ventures included the Pennsylvania Gazette and Poor Richard’s Almanack , a collection of homespun proverbs advocating hard work and honesty in order to get ahead. The almanac, which Franklin first published in 1733 under the pen name Richard Saunders, included such wisdom as: “Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.”

Whether or not Franklin followed this advice in his own life, he came to represent the classic American overachiever. In addition to his accomplishments in business and science, he is noted for his numerous civic contributions. Among other things, he developed a library, insurance company, city hospital and academy in Philadelphia that would later become the University of Pennsylvania.

Most significantly, Franklin was one of the founding fathers of the United States and had a career as a statesman that spanned four decades. He served as a legislator in Pennsylvania as well as a diplomat in England and France. He is the only politician to have signed all four documents fundamental to the creation of the U.S.: the Declaration of Independence (1776), the Treaty of Alliance with France (1778), the Treaty of Paris (1783), which established peace with Great Britain and the U.S. Constitution (1787).

Franklin died at age 84 on April 17, 1790, in Philadelphia. He remains one of the leading figures in U.S. history.

Benjamin Franklin’s Kite Experiment: What Do We Know?

Surprisingly little.

11 Surprising Facts About Benjamin Franklin

The United States’ original renaissance man created some unusual inventions—and was a passionate swimmer.

The Eventful Life of Benjamin Franklin

The Pennsylvania scientist and diplomat signs both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

Also on This Day in History June | 10

In brutal reprisal, Nazis annihilate Czech village of Lidice

“where the wild things are” author maurice sendak is born, this day in history video: what happened on june 10, six‑day war ends, norway surrenders to germany, nelson mandela’s first major political statement from prison is published .

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

First Salem witch hanging

British vessel burned off rhode island, alcoholics anonymous founded, italy declares war on france and great britain, general westmoreland gives farewell press conference in saigon, joe nuxhall makes mlb debut at 15, tolstoy disguises himself as a peasant and leaves on a pilgrimage, last episode of “the sopranos” airs, famous scene from "gone with the wind" filmed.

Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

The kite experiment, 19 october 1752, the kite experiment.

I. Printed in The Pennsylvania Gazette , October 19, 1752; also copy: The Royal Society. II. Printed in Joseph Priestley, The History and Present State of Electricity, with Original Experiments (London, 1767), pp. 179–81.

Franklin was the first scientist to propose that the identity of lightning and electricity could be proved experimentally, but he was not the first to suggest that identity, nor even the first to perform the experiment. 4 For many years pioneer electricians had noted the similarity between electrical discharges and lightning, and in 1746 John Freke in England and Johann Heinrich Winkler in Germany separately advanced the idea of identity and suggested theories to account for it. Franklin’s later adversary the Abbé Nollet wrote to the same effect in 1748. 5 Franklin and his Philadelphia collaborators, working independently, also observed the similarities, and in his letter of April 29, 1749, to John Mitchell on thundergusts he took as the basis for his entire discussion the hypothesis that clouds are electrically charged. 6 In the “minutes” he kept of his experiments he listed under the date of November 7, 1749, twelve particulars in which “electrical fluid agrees with lightning,” and noted further that “the electrical fluid is attracted by points,” but that it was not yet known whether this property was also in lightning. “But since they agree in all other particulars wherein we can already compare them, is it not probable they agree likewise in this? Let the experiment be made.” 7

However obvious the suggestion of such an experiment may now seem, no one had made it before. Herein lies Franklin’s principal claim to priority in this great discovery. A test of lightning required the prior discoveries embodied in the “doctrine of points,” of which he was the undisputed author, and the knowledge he had gained of the role of grounding in electrical experiments. It was the pointed metal rod, with its peculiar effectiveness in electrical discharge, which both led to the suggestion and facilitated the experiment.

In the following March Franklin, writing to Collinson, suggested that pointed rods, instead of the usual round balls of wood or metal, be placed on the tops of weathervanes and masts, and that they would draw the electrical fire “out of a cloud silently,” thereby preserving buildings and ships from being struck by lightning. 8 He repeated the suggestion in July 1750 in his “Opinions and Conjectures,” with the important addition that a wire be run down from the rod to the ground or water, and he then proposed the “sentry-box” experiment. This was the first public suggestion of an experiment to prove the identity of lightning and electricity. 9

According to Joseph Priestley, who almost certainly received his information directly from Franklin about fifteen years later, he did not perform the experiment himself at once because he believed a tower or spire would be needed to reach high enough to attract the electrical charge from a thunder cloud, and there was no structure in Philadelphia he deemed adequate for the purpose. Presumably he was waiting until Christ Church steeple, then in the early discussion stage, should be erected. 1 English scientists, who could have read Franklin’s proposal when it was published in Experiments and Observations in April 1751, apparently failed to recognize its significance. But about a year later, in the spring of 1752, when a translation had been published in Paris, the French reaction was very different. Delor, “master of experimental philosophy,” repeated most of Franklin’s experiments before the King, and then in May Dalibard, Franklin’s translator, and Delor each set up apparatus which performed successfully the “Philadelphia experiment” of drawing electricity from a thunder cloud. 2 Word of these achievements awoke the English electricians, and during the summer of 1752 the experiment was repeated several times in England as well as in France and Germany. 3

At some time during 1751 or 1752 Franklin got the idea that he could send his conductor high enough by means of a kite, and that if it were flown during a thunder shower, the wet string might serve to bring the electrical charge down within reach. When the idea first came to him and just when he carried it out cannot be established with absolute certainty. Priestley wrote that the famous experiment with kite and key took place during June 1752, and the present editors believe there is no good reason to doubt the correctness of this date. If so, then Franklin performed his experiment before he learned of what Dalibard and Delor had done in France.

Almost never during these years did Franklin report a particular electrical experiment until some time had elapsed and this affair seems to have been no exception. Word of Dalibard’s and Delor’s successes reached Philadelphia toward the end of August and the Pennsylvania Gazette of August 27 carried a short account reprinted from the May issue of the London Magazine . During September Franklin erected a lightning rod on his own house, ingeniously equipping it with bells that would ring when the wire became charged and thus notify him when the atmosphere above the house was electrified. 4 Then at last, on October 19, he printed in the Gazette a brief statement about the kite experiment with instructions for repeating it. The text of this statement, transmitted to Collinson, was read to the Royal Society on December 21. Neither in this paper nor at any later time did Franklin—or Priestley on his behalf—ever claim priority in carrying out the experiment he had been the first to propose. 5

The same October 19 issue of the Gazette also announced that Poor Richard for 1753 was then “In the Press, and speedily will be published”; in that almanac Franklin printed for the first time precise instructions for the erection of lightning rods for the protection of buildings. 6 The sequence of events in this somewhat complicated chain may be clarified by the following chronology:

Unfortunately, Franklin’s statement of the kite experiment has not been found in his own handwriting. Two text versions survive: that printed in the Pennsylvania Gazette of October 19, 1752, reprinted below; and a copy in the hand of Peter Collinson, now in the Royal Society. 7 Aside from unimportant variations in paragraphing, spelling, capitalization, and punctuation, the Collinson copy differs from the Gazette version in several respects: (1) It is headed “From Benn: Franklin Esqr To P Collinson” and is dated “Philadelphia Octo: 1: 1752.” (2) At the end, following the words “compleatly demonstrated,” Collinson skipped the equivalent of about three lines, then added in two lines: “See his Kite Experiment” and “to be printed with the rest.” These lines were later struck out. (3) In the intervening space and running on to the right of the two canceled lines appears the following insertion not in Collinson’s hand, but in one which is strikingly like that of William Watson: “I was pleased to hear of the Success of my experiments in France, and that they there begin to Erect points on their buildings. Wee had before placed them upon our Academy and Statehouse Spires.” (4) The paper is endorsed in the hand of a Royal Society clerk: “Letter of Benjamin Franklin Esq to Mr. Peter Collinson F.R.S. concerning an Electrical Kite. Read at R.S. 21 Decemb. 1752. Ph. Trans. XLVII . p. 565.”

These text differences present several puzzles. The heading and date (item 1) have led several writers 8 to believe that the text which follows is an extract of a letter from Franklin to Collinson of October 1, written more than two weeks before the statement was printed in the Gazette . In that case the Gazette text would be an extract from this earlier letter to Collinson. This is possible, but it leaves unexplained Franklin’s undated letter to Collinson, assigned below (p. 376) to the latter part of October, in which he wrote that he was sending, among other items, “my kite experiment in the Pennsylvania Gazette .” If what he had printed in the Gazette was indeed a passage from a letter already sent to Collinson, there would seem to have been no need to send him another copy of it. Conceivably, Collinson’s pen slipped when he wrote “Octo: 1,” as it occasionally did in referring to other Franklin letters, and he should have written “19,” “21,” or “31,” in which case he might have been copying the Gazette statement enclosed in Franklin’s later letter. Subsequent correspondence between the two men does not clarify the point.

The canceled addendum at the bottom (item 2) seems to have been intended as an instruction to a printer. Possibly Collinson first meant this paper for the printer of the 1753 Supplement of Experiments and Observations , and then decided to submit this copy to the Royal Society instead. But the question remains unexplained why he should have written “See his Kite Experiment,” when this document itself is the kite experiment, and is the only account of it we have in Franklin’s own words. The endorsement (item 4) presents no problem. The fact that the paper is lodged in the Royal Society makes it clear that this endorsement was added later for filing purposes after it had been printed in the Philosophical Transactions .

This leaves for consideration item 3, the short paragraph added to Collinson’s paper which mentions the French experiments and the erection of “points” in France and Philadelphia. The facts that it is written in a different hand from Collinson’s and that it is clearly an addition have not been considered by previous commentators. The paragraph has been taken as evidence that lightning rods were erected on the Academy building and the State House (Independence Hall) before October 1, 1752. The words are doubtless Franklin’s, though they have not been traced with certainty to any surviving document of his. If they were in fact part of a letter of October 1 to Collinson which also contained the original text of the statement on the kite experiment, then they must have been added to Collinson’s copy by someone else, probably Watson, who saw the original letter and thought this passage more important than Collinson had done. Or the paragraph may have been part of the later undated letter, probably of late October (the full text of which may not have been printed in the 1753 Supplement), with which Franklin enclosed the item on the kite experiment from the Gazette . Whatever the source, the paragraph must have been written by about November 1, 1752, in order for it to be read to the Royal Society as part of the report on the kite experiment on December 21 and printed as such in the Philosophical Transactions . 9 The probable date for the erection of the two Philadelphia lightning rods is not materially affected in any case. The problem of the source of this added paragraph is not resolved by any printed version of Franklin’s account. The Philosophical Transactions printed the text from Collinson’s copy. The Gentleman’s Magazine and London Magazine and the 1753 Supplement to Experiments and Observations also printed the report, but all three followed the dating and text of the Gazette version, not the Collinson copy. 1

It will be noticed that Franklin’s paper is not really an account of the kite experiment, but rather a brief statement that the experiment had taken place, followed by instructions as to how it could be successfully repeated. Franklin never, so far as is known, wrote out a narrative of his experience. The most detailed account that has survived is that which Joseph Priestley inserted in 1767 in his History of Electricity . There is every reason to believe that he learned the details directly from Franklin, who was in London at the time Priestley wrote the book. Franklin encouraged him to undertake the work and Priestley acknowledged in his preface the information Watson, Franklin, and Canton had supplied him. The account of the kite experiment, as Priestley wrote it about fifteen years after the event, may err in some details through faulty memory on Franklin’s part or misunderstanding on the Englishman’s, but it is probably correct in all major respects. In any case, since it is the nearest thing we have to a contemporary, first-hand account of one of the most famous episodes in Franklin’s career, it is reprinted here directly following Franklin’s statement.

I. Franklin’s Statement

Philadelphia, October 19

As frequent Mention is made in the News Papers from Europe, of the Success of the Philadelphia Experiment for drawing the Electric Fire from Clouds by Means of pointed Rods of Iron erected on high Buildings, &c. it may be agreeable to the Curious to be inform’d, that the same Experiment has succeeded in Philadelphia, tho’ made in a different and more easy Manner, which any one may try, as follows. 2

Make a small Cross of two light Strips of Cedar, the Arms so long as to reach to the four Corners of a large thin Silk Handkerchief when extended; tie the Corners of the Handkerchief to the Extremities of the Cross, so you have the Body of a Kite; which being properly accommodated with a Tail, Loop and String, will rise in the Air, like those made of Paper; but this being of Silk is fitter to bear the Wet and Wind of a Thunder Gust without tearing. To the Top of the upright Stick of the Cross is to be fixed a very sharp pointed Wire, rising a Foot or more above the Wood. To the End of the Twine, next the Hand, is to be tied a silk Ribbon, and where the Twine and the silk join, a Key may be fastened. This Kite is to be raised when a Thunder Gust appears to be coming on, and the Person who holds the String must stand within a Door, or Window, or under some Cover, so that the Silk Ribbon may not be wet; and Care must be taken that the Twine does not touch the Frame of the Door or Window. As soon as any of the Thunder Clouds come over the Kite, the pointed Wire will draw the Electric Fire from them, and the Kite, with all the Twine, will be electrified, and the loose Filaments of the Twine will stand out every Way, and be attracted by an approaching Finger. And when the Rain has wet the Kite and Twine, so that it can conduct the Electric Fire freely, you will find it stream out plentifully from the Key on the Approach of your Knuckle. At this Key the Phial may be charg’d; and from Electric Fire thus obtain’d, Spirits may be kindled, and all the other Electric Experiments be perform’d, which are usually done by the Help of a rubbed Glass Globe or Tube; and thereby the Sameness of the Electric Matter with that of Lightning compleatly demonstrated.

II. Priestley’s Account

To demonstrate, in the completest manner possible, the sameness of the electric fluid with the matter of lightning, Dr. Franklin, astonishing as it must have appeared, contrived actually to bring lightning from the heavens, by means of an electrical kite, which he raised when a storm of thunder was perceived to be coming on. This kite had a pointed wire fixed upon it, by which it drew the lightning from the clouds. This lightning descended by the hempen string, and was received by a key tied to the extremity of it; that part of the string which was held in the hand being of silk, that the electric virtue might stop when it came to the key. He found that the string would conduct electricity even when nearly dry, but that when it was wet, it would conduct it quite freely; so that it would stream out plentifully from the key, at the approach of a person’s finger. 3

At this key he charged phials, and from electric fire thus obtained, he kindled spirits, and performed all other electrical experiments which are usually exhibited by an excited globe or tube.

As every circumstance relating to so capital a discovery as this (the greatest, perhaps, that has been made in the whole compass of philosophy, since the time of Sir Isaac Newton) cannot but give pleasure to all my readers, I shall endeavour to gratify them with the communication of a few particulars which I have from the best authority.

The Doctor, after having published his method of verifying his hypothesis concerning the sameness of electricity with the matter of lightning, was waiting for the erection of a spire in Philadelphia to carry his views into execution; not imagining that a pointed rod, of a moderate height, could answer the purpose; when it occurred to him, that, by means of a common kite, he could have a readier and better access to the regions of thunder than by any spire whatever. Preparing, therefore, a large silk handkerchief, and two cross sticks, of a proper length, on which to extend it; he took the opportunity of the first approaching thunder storm to take a walk into a field, in which there was a shed convenient for his purpose. But dreading the ridicule which too commonly attends unsuccessful attempts in science, he communicated his intended experiment to no body but his son, who assisted him in raising the kite. 4

The kite being raised, a considerable time elapsed before there was any appearance of its being electrified. One very promising cloud had passed over it without any effect; when, at length, just as he was beginning to despair of his contrivance, he observed some loose threads of the hempen string to stand erect, and to avoid one another, just as if they had been suspended on a common conductor. Struck with this promising appearance, he immediately presented his knucle to the key, and (let the reader judge of the exquisite pleasure he must have felt at that moment) the discovery was complete. He perceived a very evident electric spark. Others succeeded, even before the string was wet, so as to put the matter past all dispute, and when the rain had wet the string, he collected electric fire very copiously. This happened in June 1752, a month after the electricians in France had verified the same theory, but before he heard of any thing they had done.

4 . The best discussion of this entire topic is I. Bernard Cohen, “The Two Hundredth Anniversary of Benjamin Franklin’s Two Lightning Experiments and the Introduction of the Lightning Rod,” APS Proc , XCVI (1952), 331–66. The present editors are in full agreement with Cohen’s conclusions except, as this headnote will show, those derived specifically from consideration of the Collinson copy of BF ’s statement on the kite experiment.

5 . Cohen, BF’s Experiments , pp. 104–9, discusses the matter with citations and quotations from various writers.

6 . See above, III , 365–76.

7 . Quoted by BF in his letter to John Lining, March 18, 1755 , Exper. and Obser. 1769, p. 323. The originals of BF ’s minutes have not survived.

8 . See above, III , 472–3

9 . See above, pp. 19–20.

1 . See above, p. 116.

2 . See above, pp. 302–10, 315–17.

3 . See below, 390–2.

4 . BF to Collinson, September 1753.

5 . Writing in 1788 in his autobiography, BF mentions the Dalibard and Delor successes with the “Philadelphia experiments” and then adds simply and with disappointing brevity: “I will not swell this Narrative with an Account of that capital Experiment, nor of the infinite Pleasure I receiv’d in the Success of a similar one I made soon after with a Kite at Philadelphia, as both are to be found in the Histories of Electricity.” Par. Text edit., p. 386.

6 . See below, p. 408.

7 . The Collinson copy is reproduced in facsimile in APS Proc. , XCVI , pp. 334–5.

8 . Notably Cohen in the works cited in the first two footnotes to this headnote, and Carl Van Doren in Franklin , p. 169, and Autobiographical Writings , p. 76.

9 . The paragraph could be from some now missing letter of later date than about Nov. 1, 1752, only in the unlikely circumstance that it was added to the Collinson copy between the reading of the paper on December 21 and the transmission of this number of Phil. Trans. to the printer sometime in 1753.

1 . Gent. Mag. , XXII (1752), 560–1; London Mag. , XXI (1752), 607–8; Supplemental Experiments and Observations on Electricity, Part II (London, 1753), pp. 106–8. Gent. Mag. and the 1753 Supplement both add the initials “B.F.” at the end; London Mag. omits the first paragraph and begins “Make a small cross, …” but otherwise follows the Gazette version.

2 . In 1760 and later printed editions: “which is as follows:”

3 . At this point Priestley inserted a footnote reference to Exper. and Obser ., p. 106, where BF ’s statement is printed.

4 . At this time William Franklin was at least 21 years old (see above, III , 474), not the child shown in the well-known Currier and Ives print depicting the scene. There are a number of other errors in the picture.

Index Entries

You are looking at.

The True Story Behind Ben Franklin's Lightning Experiment

In elementary school, most of us were taught that Benjamin Franklin discovered electricity by tying a key to a kite and standing in a thunderstorm. Though Franklin is believed to have completed his lightning experiment, he wasn’t the first to do so. Nor was he the first scientist to study charged particles. Sorry everyone, your childhood science teacher sort of lied to you. So let’s clear things up.

Founding Father/diplomat/inventor/innovator/Philadelphian/total cad Benjamin Franklin became interested in the field of electricity when his friend and fellow scientist Peter Collinson sent him an electricity tube. Franklin investigated how charged objects interacted and came to the conclusion that lightning was merely a huge spark that was created by charged forces. In this early phase of experimentation, Franklin concluded that electricity was fluid.

It was during this time, in 1750, that Franklin sent Collinson a letter proposing an experiment that would draw lightning through a 30-foot rod. He not only hypothesized that lightning and electricity were linked, but that metal objects could be used to draw lightning in order to protect homes from being hit. But Franklin didn’t feel that he could get his conductor high enough into the clouds to do any good, so he never completed the experiment. Instead, in 1752, he devised a new plan: sending a kite into the air.

Little did Franklin know that his original letter to Collinson, once translated to French, was causing quite a stir in Paris. To test Franklin’s hypothesis, naturalist Thomas-Francois Dalibard used a large metal pole to conduct electricity from lightning on May 10, 1752. In Dalibard’s writing of his Paris experiment, he concluded that Franklin’s hypothesis was right .

It was exactly one month after the Dalibard experiment, on June 10, 1752, that Franklin (supposedly) performed his famous kite and key experiment. Franklin stood outside under a shelter during a thunderstorm and held on to a silk kite with a key tied to it. When lightning struck, electricity traveled to the key and the charge was collected in a Leyden jar .

Here’s the tricky bit—there is a lot of doubt between historians as to whether or not Franklin ever conducted the experiment.

In October of 1752, Franklin wrote a brief statement in the Pennsylvania Gazette saying that the iron rod experiment had been achieved in Philadelphia, but “in a different and more easy Manner,” with a kite. But as his previous thought experiment was being replicated across the continent with great success, this was only of minor scientific interest and Franklin never really elaborated on it. Also, he never said that he was the one who did the experiment. It only became a story 15 years later when Joseph Priestley wrote a full description in which he describes Franklin as bringing “lightning from the clouds” to the ground.

As modern scientists have come to discover, if Franklin had performed the experiment as delineated in Priestley’s account, Franklin would have been struck dead on the spot . In his 1752 article, Franklin claimed you could touch the key and feel a spark; however, that much charge would have sizzled his insides. But other historians read his original statement in the Gazette and think it’s been misinterpreted. Instead of getting hit by lightning, the kite just picked up the ambient electric charge—Franklin was lucky that his kite never got a direct hit.

So, while we can credit Franklin for writing up the experiment that posits whether lightning is the same as electricity and can be drawn through metal, he was not the first to actually perform said experiment and write about its results. In fact, there are few sources that can prove Franklin ever did the kite experiment at all—we have to trust his word that it happened.

COMMENTS

On June 10, 1752, Benjamin Franklin took a kite out during a storm to see if a key attached to the string would draw an electrical charge. Or so the story goes. In fact, historians aren’t...

The kite experiment is a scientific experiment in which a kite with a pointed conductive wire attached to its apex is flown near thunder clouds to collect static electricity from the air and conduct it down the wet kite string to the ground. The experiment was first proposed in 1752 by Benjamin Franklin, who reportedly conducted the experiment ...

Here’s how the experiment worked: Franklin constructed a simple kite and attached a wire to the top of it to act as a lightning rod. To the bottom of the kite he attached a hemp string, and to that he attached a silk string.

On a dark, stormy summer night in 1752, Benjamin Franklin flew a kite with a key attached to the string waiting in anticipation for lightning to strike. The dramatic bolt would harken the...

By conducting the kite experiment Franklin proved that lighting was an electrical discharge and realized that it can be charged over a conductor into the ground providing a safe alternative path and eliminating the risk of deadly fires.

What was Benjamin Franklin’s kite experiment? Of course, what really made Franklin a world-famous scientist was his legendary kite experiment, so famous that it even gets a namedrop in the musical Hamilton – that is, despite ongoing uncertainty whether it happened at all.

Benjamin Franklin flies a kite during a thunderstorm and collects ambient electrical charge in a Leyden jar, enabling him to demonstrate the connection between lightning and electricity.

At some time during 1751 or 1752 Franklin got the idea that he could send his conductor high enough by means of a kite, and that if it were flown during a thunder shower, the wet string might serve to bring the electrical charge down within reach.

Franklin investigated how charged objects interacted and came to the conclusion that lightning was merely a huge spark that was created by charged forces. In this early phase of experimentation,...

This kite is to be raised when a thunder gust appears to be coming on, and the person who holds the string must stand within a door, or window, or under some cover, so that the silk ribbon may not be wet; and care must be taken that the twine does not touch the frame of the door or window.