- General Categories

- Mental Health

- IQ and Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

Little Albert Experiment: A Landmark Study in Classical Conditioning

A single, terrified cry echoed through the laboratory as Little Albert, an innocent infant, unknowingly became the centerpiece of a groundbreaking experiment that would forever change our understanding of human behavior and the power of classical conditioning. This haunting moment marked the beginning of one of the most controversial and influential studies in the history of psychology, setting the stage for decades of research and ethical debates to come.

The Little Albert experiment, conducted in 1920 by John B. Watson and his graduate student Rosalie Rayner, was a landmark study that sought to demonstrate how classical conditioning could be applied to human emotions and behavior. But what exactly is classical conditioning, and why was this particular experiment so significant?

The Foundations of Classical Conditioning

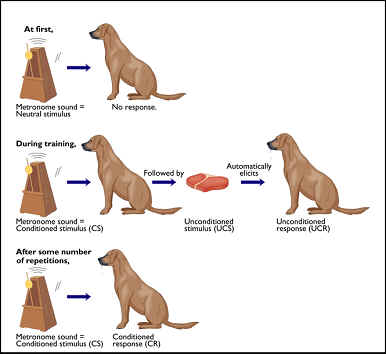

Classical conditioning, first discovered by Ivan Pavlov in his famous experiments with dogs, is a learning process that occurs through associations between an environmental stimulus and a naturally occurring stimulus. This fundamental concept forms the backbone of behaviorism, a psychological approach that dominated the field in the early 20th century.

To truly appreciate the impact of the Little Albert experiment, we must first understand the historical context in which it took place. The early 1900s saw a shift in psychological thinking, moving away from introspection and towards more observable and measurable behaviors. This era gave birth to behaviorism, a school of thought that emphasized the role of environmental factors in shaping human behavior.

John B. Watson, often referred to as the father of behaviorism, was at the forefront of this movement. His bold claim that he could take any healthy infant and, through careful conditioning, mold them into any type of specialist he desired – “doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief, and, yes, even beggar-man and thief” – set the stage for the Little Albert experiment.

The Birth of a Controversial Study

Watson’s goals for the Little Albert experiment were ambitious and, by modern standards, ethically questionable. He aimed to demonstrate that emotional responses could be conditioned in humans, just as Pavlov had shown with his dogs. This hypothesis, if proven, would have far-reaching implications for our understanding of human psychology and the development of fears and phobias.

The subject of this groundbreaking study was a 9-month-old infant known as “Albert B.” Little Albert, as he came to be called, was selected from a hospital where his mother worked as a wet nurse. The choice of such a young subject was deliberate – Watson wanted to work with a child who had not yet developed many fears or phobias.

The Experimental Design: A Blueprint for Controversy

The methodology of the Little Albert experiment was both ingenious and troubling. Watson and Rayner began by presenting Albert with various stimuli, including a white rat, a rabbit, a dog, and several masks. Initially, Albert showed no fear of these objects, even reaching out to touch them with curiosity.

Then came the crucial phase of the experiment. As Albert reached for the white rat, Watson would strike a steel bar with a hammer, creating a loud, frightening noise. This process was repeated several times, pairing the sight of the rat with the startling sound. Soon, Albert began to cry and show signs of distress at the mere sight of the rat, even without the accompanying noise.

This conditioning process demonstrated the power of Watson classical conditioning , showing how a neutral stimulus (the rat) could become associated with an aversive stimulus (the loud noise) to produce a conditioned fear response. The implications were profound, suggesting that human emotions and behaviors could be shaped through environmental associations.

The Ripple Effect: Generalization and Its Consequences

Perhaps the most striking finding of the Little Albert experiment was the generalization of Albert’s fear response. Not only did he become afraid of the white rat, but he also showed fear towards similar objects, including a rabbit, a dog, and even a Santa Claus mask with white fur trim. This generalization demonstrated how conditioned fears could extend beyond the original stimulus, potentially explaining the development of phobias in real-world situations.

However, the experiment was not without its limitations and criticisms. One glaring omission was the lack of any attempt to extinguish Albert’s newly acquired fears. In modern respondent conditioning in ABA (Applied Behavior Analysis), the process of extinction – gradually reducing the conditioned response – is considered crucial. This oversight left many questions unanswered about the long-term effects of the conditioning and the potential for reversing such learned fears.

The Ethical Quagmire: A Study That Shaped Research Practices

The Little Albert experiment stands as a stark reminder of the ethical considerations that must guide psychological research. By today’s standards, the study would be considered highly unethical. Inducing fear in an infant, without parental consent or any plan for removing the conditioned fear, raises serious moral questions.

This experiment, along with other controversial studies of its time, played a significant role in shaping modern research ethics. It sparked debates about the rights of research subjects, especially vulnerable populations like children, and led to the development of strict ethical guidelines that govern psychological research today.

The Hunt for Little Albert: A Mystery Unsolved

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Little Albert story is the mystery surrounding the true identity of the infant. For decades, psychologists and historians have attempted to uncover what became of Little Albert after the experiment. Various theories and claims have emerged, but the truth remains elusive.

This ongoing mystery has kept the Little Albert experiment in the public eye, sparking discussions about the long-term consequences of early psychological interventions and the responsibility of researchers to their subjects. It serves as a poignant reminder of the human element in scientific research and the potential for unforeseen consequences.

The Legacy of Little Albert in Modern Psychology

Despite its ethical shortcomings, the Little Albert experiment has left an indelible mark on the field of psychology. It demonstrated the applicability of classical conditioning principles to human behavior, paving the way for further research into learning and behavior modification.

The study’s influence can be seen in various areas of psychology, from the development of behavior therapy techniques to our understanding of the origins of phobias. It has also played a crucial role in shaping our approach to child psychology and parenting, highlighting the potential impact of early experiences on emotional development.

Replication and Modern Interpretations

In recent years, there have been attempts to replicate and reanalyze the Little Albert experiment using modern research methods. These efforts have shed new light on Watson and Rayner’s original findings while also raising questions about the study’s methodology and conclusions.

One notable replication attempt, conducted in 2009, used ethically appropriate methods to test the conditioning of fear responses in infants. While the results supported some of Watson’s findings, they also highlighted the complexity of human learning and the limitations of the original study.

The Intersection of Classical and Instrumental Conditioning

The Little Albert experiment primarily focused on classical conditioning, but it’s important to note its relationship to other forms of learning, such as instrumental conditioning . While classical conditioning deals with involuntary responses to stimuli, instrumental conditioning involves learning through the consequences of voluntary behaviors.

The interplay between these two forms of conditioning has been a subject of much research since Watson’s time. Modern psychologists recognize that both processes often work in tandem, shaping complex human behaviors and emotions.

Beyond Little Albert: The Evolution of Conditioning Research

The Little Albert experiment was just the beginning of a rich field of study in behavioral psychology. Subsequent researchers have expanded on Watson’s work, exploring various aspects of conditioning and learning. For instance, the concept of latent conditioning emerged, suggesting that learning can occur even when the association between stimuli is not immediately apparent.

Another fascinating area of research that grew from the foundations laid by Watson is observational conditioning . This form of learning occurs when individuals acquire new behaviors or emotional responses by watching others, rather than through direct experience. It’s a testament to the complexity of human learning and the diverse ways in which our behaviors can be shaped.

The Dark Side of Conditioning: Aversive Techniques and Ethical Concerns

The Little Albert experiment also opened the door to discussions about aversive conditioning , a controversial technique that uses unpleasant stimuli to modify behavior. While aversive conditioning has been used in various therapeutic contexts, it remains a subject of ethical debate, much like the original Little Albert study.

These ethical considerations have led to the development of more positive reinforcement-based approaches in behavioral therapy, as exemplified by the use of the Operant Conditioning Chamber in research and clinical settings. This shift reflects a growing understanding of the potential harm associated with aversive techniques and a commitment to more humane and effective methods of behavior modification.

The Enduring Impact of Little Albert

As we reflect on the Little Albert experiment nearly a century later, its significance in the history of psychology remains undeniable. It serves as a powerful example of how a single study can shape an entire field of research, influencing everything from theoretical frameworks to ethical guidelines.

The experiment continues to be a staple in psychology textbooks, not just for its demonstration of classical conditioning principles, but also as a cautionary tale about the ethical responsibilities of researchers. It prompts students and professionals alike to grapple with complex questions about the balance between scientific inquiry and human welfare.

Moreover, the Little Albert study has left an indelible mark on popular culture, inspiring countless discussions, debates, and even works of fiction. It has become a symbol of both the potential and the perils of psychological research, reminding us of the profound impact our early experiences can have on our emotional development.

In conclusion, the Little Albert experiment, despite its ethical flaws, remains a pivotal moment in the history of psychology. It demonstrated the power of classical conditioning in humans, opened new avenues of research in behavioral psychology, and sparked crucial discussions about research ethics. As we continue to unravel the complexities of human behavior and learning, the legacy of Little Albert serves as both a foundation and a cautionary tale, reminding us of the responsibility we bear when exploring the depths of the human mind.

References:

1. Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3(1), 1–14.

2. Harris, B. (1979). Whatever happened to little Albert? American Psychologist, 34(2), 151–160.

3. Beck, H. P., Levinson, S., & Irons, G. (2009). Finding Little Albert: A journey to John B. Watson’s infant laboratory. American Psychologist, 64(7), 605–614.

4. Fridlund, A. J., Beck, H. P., Goldie, W. D., & Irons, G. (2012). Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child. History of Psychology, 15(4), 302–327.

5. Powell, R. A., Digdon, N., Harris, B., & Smithson, C. (2014). Correcting the record on Watson, Rayner, and Little Albert: Albert Barger as “Psychology’s Lost Boy”. American Psychologist, 69(6), 600–611.

6. Todd, J. T. (1994). What psychology has to say about John B. Watson: Classical behaviorism in psychology textbooks, 1920–1989. In J. T. Todd & E. K. Morris (Eds.), Modern perspectives on John B. Watson and classical behaviorism (pp. 75–107). Greenwood Press/Greenwood Publishing Group.

7. Rescorla, R. A. (1988). Pavlovian conditioning: It’s not what you think it is. American Psychologist, 43(3), 151–160.

8. Guthrie, E. R. (1935). The psychology of learning. Harper & Brothers.

9. Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

10. Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Was this article helpful?

Would you like to add any comments (optional), leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Resources

Excitatory Conditioning: Enhancing Learning and Behavior Through Positive Reinforcement

Antecedent Operant Conditioning: Shaping Behavior Through Environmental Cues

Rule-Governed Behavior: Shaping Actions Through ABA Principles

Intermittent Conditioning: Revolutionizing Fitness and Performance

Operant Conditioning Terms: A Comprehensive Guide to Behavioral Psychology

Conditioning: A Comprehensive Guide to Its Meaning and Applications

Acquisition Phase of Classical Conditioning: Key Principles and Applications

Modeling Conditioning: Techniques for Enhancing Model Performance and Stability

Subconscious Conditioning: Shaping Your Mind for Success and Well-being

Hiking Conditioning: Essential Training for Peak Trail Performance

Psychologized

Psychology is Everywhere...

The Little Albert Experiment

Little Albert was the fictitious name given to an unknown child who was subjected to an experiment in classical conditioning by John Watson and Rosalie Raynor at John Hopkins University in the USA, in 1919. By today’s standards in psychology, the experiment would not be allowed because of ethical violations, namely the lack of informed consent from the subject or his parents and the prime principle of “do no harm”. The experimental method contained significant weaknesses including failure to develop adequate control conditions and the fact that there was only one subject. Despite the many short comings of the work, the results of the experiment are widely quoted in a range of psychology texts and also were a starting point for understanding phobias and the development of treatments for them.

What happened to Little Albert as he was known is unknown and several psychologists have tried in vain to definitively answer the question of: “what happened to Little Albert?”

What is classical conditioning?

Classical Conditioning Explained

Classical conditioning is a type of behaviourism first demonstrated by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov in the 1890s.Through a series of experiments he demonstrated that dogs which normally salivated when presented with food could be conditioned to salivate in response to any stimulus in the absence of the original stimulus, food. He rang a bell every time a dog was about to be fed, and after a period of time the dog would salivate to the sound of the bell irrespective of food being presented.

What did Watson do to Little Albert?

Many people have illogical fears of animals. While it is logical to be frightened of a predator with the power to kill you, being afraid of a spider, a mouse or even cats and most dogs is not. To those of us who don’t suffer from phobias it is the funniest thing in the world to see a person standing on a stool, screaming because of a mouse. Phobias however are real, and for some people quite limiting and potentially damaging. Imagine suffering from agoraphobia – fear of open spaces or even being afraid of going to the dentist to the extent that your health suffered.

Now, while we know now that phobias can be learned from watching others who have a fear, for example our mother being afraid of spiders, known as social learning, Watson used the tools and knowledge he had available to him to investigate the potential causes of them ultimately, one supposes, to develop treatments for phobias.

John Watson endeavoured to repeat classical conditioning on a young emotionally stable child, with the objective of inducing phobias in the child. He was interested in trying to understand how children become afraid of animals.

Harris (1979) suggested: ‘Watson hypothesized that although infants do not naturally fear animals, if “one animal succeeds in arousing fear, any moving furry animal thereafter may arouse it”

Albert was 9 months old and taken from a hospital, subjected to a series of baseline tests and then a series of experiences to ‘condition’ him. Watson filmed his study on Little Albert and the recordings are accessible on Youtube.com.

A series of unethical experiments was conducted with Little Albert

Watson started by introducing Albert to a number of furry animals, including a dog, a rabbit and most importantly a white rat. Watson then made loud, unpleasant noises by clanging a metal bar with a hammer. The noise distressed Albert. Watson then paired the loud noise with the presentation of the rat to Albert. He repeated this many times. Very quickly Albert was conditioned to expect the frightening noise whenever the white rat was presented to him. Very soon the white rate alone could induce a fear response in Albert. What was interesting was that without need for further conditioning the fear was generalised to other animals and situations including a dog, rabbit and a white furry mask worn by Watson himself.

Watson and Raynor who knew all along the timescale by when Albert had to be returned to his mother, gave him back without informing her of the activities and conditioning that they had inflicted on Albert, and most worryingly not taking the time to counter condition or ‘curing’ him of the phobia they had induced.

What were the problems with this the way this study was done?

Both the American Psychological Association (APA) and the British Psychological Society (BPS) have well developed codes of ethics which any practicing psychologists have to adhere to. In addition, all places of higher learning and research have ethical committees to which research proposals have to be submitted for consideration. The core concern is to focus on the quality of research, the professional competence of the researchers and of greatest importance, the welfare of human and animal subjects. At the time of Watson and Raynor’s work, there were no such guidelines and committee. While to some extent, it is wrong to measure historical research by modern-day standards, this experiment is almost a case study in unethical research. The experiment broke the cardinal ethical rules for psychological research. Those being:

- Do no harm . Psychologists have to reduce or eliminate the potential that taking part in a study may cause harm to a participant during and afterwards. Little Albert was harmed during and would potentially have suffered life-long harm as a result.

- The participants’ right to withdraw. Nowadays, if you are involved as participant in any psychological or medical study you are given the right that you can withdraw at any stage during the study without consequence to you. Albert and his mother were given no-such rights.

- The principle of informed consent. Subjects have to be given as much information about the study as possible before the study begins so that they can make a decision about participating based on knowledge. If the research is such that giving information before the study may affect the outcome then an alternative is a thorough debrief at its conclusion. Neither of these conditions was satisfied by Watson’s treatment of Albert.

- Professional competence of the researcher. While it may seem presumptive to question the behaviour of the father of “behavioural psychology”, the method used in this study was not particularly good psychology. There was only one subject and the experiment lacks any form of control. Such criticism however, is a little post hoc since research in psychology at that time was in its infancy.

Besides the ethical issues with the experiment, as can be seen from the recordings, the environment was not controlled, the animals changed, and several appeared themselves to be in distress. The final act of Watson applying a mask was presented very closely to Albert, something that potentially would cause any child distress.

Watson could have ‘cured’ Albert of the phobia he had induced using a process known as systematic desensitisation but chose not to as he and Raynor wanted to continue with the experiment until the Albert’s mother came to collect him.

Watch a Recap of this experiment in this video:

Harris B (1979): Whatever happened to Little Albert ? American Psychologist, February 1979, pp 151-160

Code of Ethics:

http://www.bps.org.uk/what-we-do/ethics-standards/ethics-standards

About Alexander Burgemeester

2 Responses to “The Little Albert Experiment”

Read below or add a comment...

what are the laws of classical conditioning in this experiment

Wow, this entire article is full of inaccuracies. Firstly, they didn’t begin the conditioning experiments on Albert until he was 11 months and 3 days old. While the first few original reactions with the different animals did not need further conditioning, the steel rod was struck several times throughout the experiment to reinstate the fear response with the stimuli. Also, it is only speculated that Albert’s mother was unaware that these experiments were going on. You mention that the mask in which Watson wears at the ending of the video would distress any child, but before beginning the experiments, Watson and his crew tested several different stimuli on Albert and marked any emotional responses. The masks were part of this test and did not originally trigger a response. A fear response was present after Albert was conditioned to fear the white rat and things that were visually similar. The mask had white hair attached at the top. He had a similiar response to a paper bag of white cotton wool. Lastly, the fact that your entire article is written with a secondary source (written in 1979 no less) as your only source beside the video, and never even refers to Watson’s original journal publication (which is available for free online at http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Watson/emotion.htm ) is even more of a reason to find this article flawed.

Leave A Comment... Cancel reply

IMAGES

VIDEO