Promotion of Educational Travel to Japan

- ABOUT JAPAN EDUCATIONAL TRAVEL

- arrow_right WHY JAPAN?

- arrow_right Traditional culture

- arrow_right Modern culture

- arrow_right Natural environment

- arrow_right Japanese food

- arrow_right Sports

- arrow_right Made in Japan

- arrow_right Crisis management

- arrow_right Social systems and infrastructure

- arrow_right Peace and friendship

- arrow_right SCHOOL IN JAPAN

- arrow_right JAPANESE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM

- arrow_right SCHOOL LIFE IN JAPAN

- arrow_right PLAN YOUR TRIP

- arrow_right SUGGESTED ITINERARIES

- arrow_right SCHOOL EXCHANGES

- arrow_right TIPS FOR A SUCCESSFUL ONLINE SCHOOL EXCHANGE

- arrow_right IN-PERSON EXCHANGES

- arrow_right ONLINE EXCHANGES

- arrow_right VISITOR'S VOICES

class JAPANESE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM

About Japanese Educational System and Japanese Schools.

Curriculum Outline

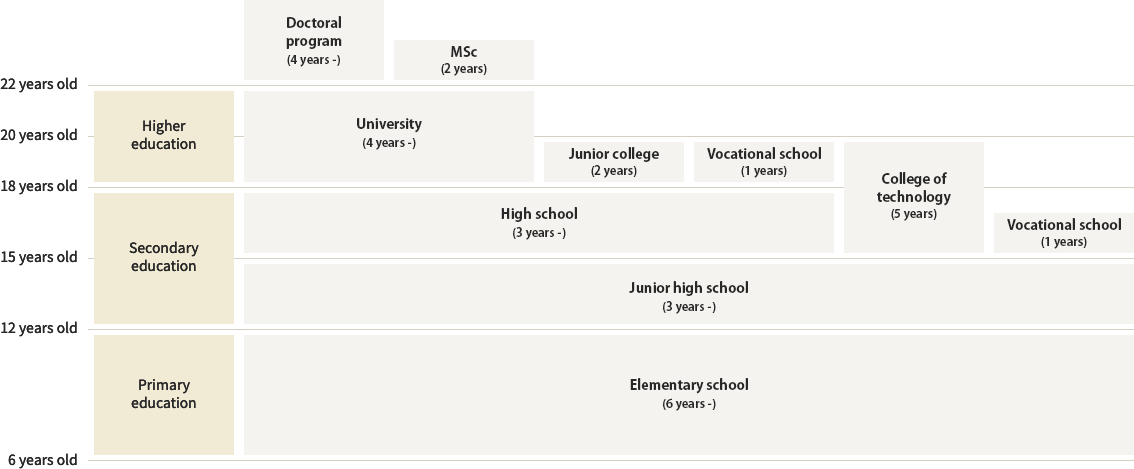

The Japanese school system primarily consists of six-year elementary schools, three-year junior high schools and three-year high schools, followed by a two-or-three-year junior colleges or a four-year colleges. Compulsory education lasts for 9 years through elementary and junior high school. School exchanges during Japan Educational Travel are mainly implemented in junior high and high schools. For physically or mentally challenged students, there is a system called “Special Needs Education” to support special students to develop their self-reliance and thus enhance their social participation.

School Education Chart

Introduction to Schools in Japan

Event school timetable.

Public schools in Japan have classes five days a week, from Monday to Friday. There are also schools that have classes on Saturday. In junior high and high schools, there are six class periods each day, typically lasting 50 minutes for each. After classes, students clean the classrooms in shifts and then start their club activities. There are a variety of clubs such as cultural and sports ones.

An Example of School Timetable

event Academic Calendar

In principle, the school year begins in April and ends in March of the following year. Most schools adopt a three-semester system, with the first semester from April to August, the second semester from September to December, and the third semester from January to March. There is also a summer break (from the end of July to the end of August), a winter break (from the end of December to the beginning of January), and a spring break (from the end of March to the beginning of April).

An Example of Academic Calendar

event School Organization

Each school has a principal, a vice principal, teachers, a school nurse, and other administration staff. As the chief executive, the principal assumes all responsibilities of the school, including the courses provided and related administrative work. The vice principal supports the principal to manage administrative affairs of the school and to be in charge of student’s educational activities and curriculum as well. Furthermore, in order to ensure school’s smooth operation, teachers take on various responsibilities, such as taking care of educational activities, students’school life, and employment guidance for students after graduation. Many schools also establish their own committees, for example a International Exchange Promotion Committee, and others.

Related Information

Special Features of Japanese Education

About Features of Japanese Education.

event Regarding the Level of Education

The level of Japanese education is high even by world standards. In OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) aimed at fifteen-year-olds, Japanese students recorded high levels of achievement, particularly in science related areas. Educational activities outside of school also flourish, and programs leading to advanced education are implemented. Enrollment in high schools, the second-half of secondary education, reaches over 90%, and the enrollments in college are also high reaching over 50%. Admission to high schools and colleges is mainly through entrance exams, held from January to March. Source: OECD

location_city Foreign Language Education

English is a compulsory subject in junior high and high schools. There are also elementary schools that introduce English education from intermediate grade classes. In some high schools, apart from English, students are also allowed to take courses in Chinese, Korean, French, German, etc.

location_city Student Clubs

Student clubs are a characteristic part in Japan’s school education. Under teachers’ guidance, students with the same interests in sports, cultural activities, or fields of study voluntarily gather together after classes and on days off. There are also numerous student clubs revolving around Japanese traditional sports and culture, such as judo, kendo(Japanese swordsmanship), sado (Japanese tea ceremony), kado (Japanese flower arrangement), shodo (Japanese calligraphy), etc. Club activities also provide students with the chance to participate in school exchange and friendly matches.

Sports Clubs

- Track and Field

- Kendo (Japanese swordsmanship)

Culture Clubs

- School Band

- School Choir

- Kado (Japanese flower arrangement)

- Sado (Japanese tea ceremony)

- Shodo (Japanese calligraphy)

check 学校交流する場合のポイント

Check_box 1~3月は受験シーズンのため交流は難しい.

海外における教育旅行は、それぞれの国・地域によって特徴が異なると考えられるが、日本で現在受け入れている教育旅行は、日本の修学旅行のように、教師等の引率者と児童生徒で構成される団体旅行として実施されることが多い。

check_box 英語での交流が可能

Check_box 部活動も充実, stories of school exchanges.

Learn About School Life in Japan

Japanese Education System: School to Higher Education

Jamila Brown Updated on September 24, 2024 Education in Japan

Many of you reading this article would likely have finished university. However, it’s essential to understand the Japanese educational system, especially if you are in Japan or planning to move in with school-going kids or a foreigner looking for higher education in Japan.

In this article

Japanese School System

The Japanese school education system consists of 12 years, of which the first 9 years, from elementary school (6 years) to junior high school (3 years), are compulsory. After compulsory education, the next 3 years are for high school.

In Japan, compulsory education starts at age six and ends at age fifteen at the end of junior high school.

Japan performs quite well in its educational standards, and overall, school education in Japan is divided into five sections. These are as follows:

- Nursery school ( hoikuen or 保育園) – Optional

- Kindergarten ( youchien or 幼稚園) – Optional

- Elementary school ( sh ō gakk ō or 小学校) – Mandatory

- Junior high school ( Chūgakkō or 中学校) – Mandatory

- High School (高校 or Kōkō) – Optional

Once students graduate from high school in Japan, they can opt for university (daigaku or 大学) or vocational school (senmongakk ō or 専門学校) for higher education.

Cram Schools in Japan

Many Japanese students also attend cram school (“juku” or 塾) to catch up on the academic competition.

These are specialized schools that help students improve their grades or pass entrance examinations. These extended programs start after school, around 4 p.m., and, depending on the program, can end well into the evening.

Classes are held from Monday to Friday, with the occasional extra classes in schools on Saturdays. The school year starts in April and ends the following year in March.

Many Japanese schools have a three-semester system. These are as follows:

- First semester: From April to August

- Second semester: From September to December

- Third semester: From January to March

National and public primary and lower secondary Japanese schools do not charge tuition, making it essentially free for all students in Japan. Foreign children aren’t required to enroll in school in Japan, but they can also attend elementary and junior high school for free. Please check this guide for foreign students’ schooling in Japan.

However, if you wish to send your kids to international schools, you will need to pay a good amount of fees.

(Image credit: Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), Japan

Types of Japanese Schools and Ages

The typical age groups of students for elementary, junior high school, and high school in Japan are as follows:

- Elementary school for six years: (6 years old – 12 years old)

- Junior high school for three years (12 – 15 years old)

- High school for three years (15 – 18 years old)

Although high school isn’t compulsory, 99% of students nationwide pursue upper secondary education after graduating from junior high school.

There are public and private schools all across Japan. Public elementary and lower secondary schools are free, while private schools require much higher tuition fees.

All public schools are funded equally. Moreover, they have the same curriculum, and all schools have the same educational expectations nationwide. After World War II, education became more democratized to make education more accessible to low-income families.

International Schools in Japan

International schools have become more popular across Japan due to the rise of foreign residents in Japan.

While Japanese schools primarily instruct in Japanese, international schools have instructions in English. These schools are largely for children of expats and bicultural children; however, Japanese residents can also attend if they choose to. However, International schools are much more expensive than Japanese public schools.

There are many international schools across Japan, but not every school is accredited by the Ministry of Education. Some schools lack proper accreditations for Western standards as well. Therefore, if you’re interested in enrolling your children in an international school, you should do your research to make sure your children can pursue further education upon graduation.

Educational Facilities for Mentally Challenged

Physically and mentally challenged students can receive “special needs education.” This is called ‘tokubetsushienkyouiku’ (特別支援教育) and supports students in being self-reliant and enhancing their communication skills.

According to the National Institute of Special Education (NISE) 2022 report, 3.26% of the total number of students in Japan received special education in various forms. Children with more acute problems can attend specialized schools.

Most of these institutions are overseen by the local government and cater to children from kindergarten to senior high school.

Japanese School Curriculum

Students in Japan take all the basic subjects similar to those around the world. These basic subjects are math, science, Japanese, Physical Education (P.E.), Home Economics, and English. People might notice a difference between Japanese and Western schools focusing on etiquette and civics.

For the first three years of school, students don’t take exams. Therefore, the core focus of education is on establishing good manners and developing character. Students are taught to respect each other, be generous, and be kind to nature.

The curriculum becomes more academically focused once they enter the fourth grade.

Japanese education heavily emphasizes equality above everything else. While many schools in the West quickly adopt the latest technology to give their students the upper hand, most National and Public schools across Japan are very low-tech.

Basic information technology courses are offered in national and public schools in Japan, but students are generally not allowed to use electronic devices in the classroom. This is to ensure equality among all students, regardless of income level.

In some countries, if students fail to perform adequately, they will likely be held back from further improving their skills. However, in Japan, students always advance to the next grade regardless of their test scores or performance.

In Japan, even if students fail tests or skip classes, they can still join the graduation ceremony at the end of the year.

School Life in Japan

Schools across Japan don’t have a janitorial staff. Students spend 10-15 minutes cleaning the school at the end of the school day. Similarly, right before any vacation, they’ll spend 30 minutes to an hour cleaning.

Once your child becomes a student, you’ll likely notice that they’ll start spending much of their free time at school due to their club activities.

School club activities ( bukatsu or 部活) are serious business in Japan. It’s a chance for students to create friendships and learn self-discipline, but they are known for taking up most students’ time. Students choose a club to join at the start of their first year, and they rarely change. Club activities happen all year round.

Aside from school clubs, students will have other activities throughout the year, such as sports day, school marathons, trips, and school festivals.

Each school is different in what sort of activities they have, but most schools will have a school festival. It’s a chance for students to work together and show off their talents to their families and friends in the area. It is usually the year’s biggest event, and students spend months preparing for the big day.

School Exams

Exams ( shiken or 試験) are a serious part of the Japanese education system. They measure not only a student’s overall learning of the material but also the schools they’ll be able to attend, starting from elementary school.

Students who want to attend junior high school, high school, and university must take entrance exams to get into those schools. And, of course, the very best schools require the highest test scores.

University entrance exams in Japan can also be particularly tough. Every February, about half a million students across Japan sign up to take them. Students who pass can look forward to acceptance from the university they applied to.

After graduating from high school, students who fail to get admission to their desired academic institution for the next level of education are called Rōnin (浪人). Rōnin is an old Japanese term for a masterless samurai. Such students must study outside the school system for self-study to prepare for the entrance test during the next academic year.

However, the Ronin students have the option to take admission in yobikō (予備校). Yobiko is a privately run school that prepares students for college admissions.

Even if you fail to get admission during the next 2-3 years, you can keep preparing because even good universities will accept you once you pass the admission test.

The education system is changing slowly as foreign companies introduce their own customs and practices. Since many Western companies hire employees based on skill, experience, and personality rather than test scores, many schools have adapted to de-emphasize the need for testing.

Higher Education in Japan

After finishing high school, many students continue their higher education at a university or a vocational school in Japan.

There’s a saying that students study hard in high school to relax in university. Attendance often isn’t required in university. Unfortunately, since many students have to endure strict rules in high school, university is seen as a time of rebellion, at least for the first two years.

Many students start their job search (shuukatsu or 就活) at the start of their third year. It may look strange to some Westerners, but wearing black suits and changing their hair to its natural color are expected norms to secure a job upon graduation.

Vocational schools have also become more popular in Japan. These Japanese vocational schools are typically only two-year courses. These institutions focus more on teaching the skills needed for a specific occupation. Upon graduation, students are awarded the title of advanced professional.

University Programs in Japan

Bachelor’s degrees.

Bachelor’s degree programs gakushi (学士) last at least four years. However, degrees in medical dentistry, pharmacy, and veterinary program extend to six years.

Most universities start their academic year in April and end in March the following year. The first semester is from April to September, and the second is from October to March .

Some Japanese universities offer flexibility in when international students can start their program, depending on the area of research. Bachelor programs require at least 124 credits to complete.

Eligibility for a Bachelor’s program in Japan as an international student requires the applicant to have completed at least 12 years of formal education in their home country.

Those without a formal education must pass the National Entrance Examination Test. School transcripts, a personal statement, and one to two letters of recommendation are also required.

Since many international programs are taught in English, prospective students must have completed 12 years of education in English.

Students who don’t qualify must prove their English language proficiency through tests like TOEFL or IELTS .

Programs taught in Japanese are also available to international students. However, students must prove their Japanese language proficiency at an intermediate level through either the Examination for Japanese University Admission (EJU) or the JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) .

Master’s Degrees in Japan

Master’s programs or shuushi (修士) in Japanese universities combine lectures, research, student projects, and a written dissertation.

To be eligible for a Master’s degree, you must have completed a four-year bachelor’s program.

Along with university transcripts, applicants will likely need two letters of recommendation, a resume, and an outline of the research proposal.

Master’s programs in Japan last for two years and require 30 course credits to be completed.

There are several Master’s programs available in English in sciences, humanities, arts, and education. Before applying, you must provide proof of language proficiency for non-native Japanese speakers interested in enrolling in a Japanese-instructed program.

Doctorate Degrees in Japan

Doctoral programs or hakase (博士) is the highest level of academic study available in Japan.

Japanese Ph.D. programs are based on quality research and high-tech teaching techniques. Most doctoral programs in Japan last for a minimum of three years. As in any other country, admission requires completing a bachelor’s and master’s degree.

Japanese Research Programs

Students who don’t meet the university’s initial qualifications or are only interested in conducting research can enroll as a research student or kenkyusei (研究生) at a graduate school of their choosing.

Students are not eligible for academic credit or a degree upon completion of their research; however, this is an ideal route for students interested in enrolling in graduate programs before fully committing to a program.

Many students use this to improve their Japanese language skills before applying. To become a research student, applicants must receive approval from a prospective advisor of the school they wish to attend.

Scholarship Opportunities for Higher Education in Japan

Compared to the cost of university in America and many other countries, university tuition in Japan is quite reasonable.

The average tuition fee for Japanese universities is about $10,000 per academic year, but it can vary depending on the school .

Many university students rely on their families for financial support, but that might not be possible for international students. Scholarships are quite rare in Japan, but several scholarships are available to international students for various programs.

An important help during your scholarship application process is the Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO) . JASSO provides student services and is responsible for scholarships, study loans, and support for international students.

You may like to check the following links for more information about the scholarships for university education in Japan:

- Japanese Government (MEXT) Postgraduate Scholarships

- The Monbukagakusho Honors Scholarship for Privately Financed International Students

- Japanese Grant Aid for Human Resource Development Scholarship

- Asian Development Bank Japan Scholarship Program

- Scholarships available through JASSO

Individual institutions also offer merit-based scholarships for international students. Be sure to check with the student offices for their qualifications.

Higher Education in Japan for Foreigners

Japan’s reputation for high educational standards makes it a great choice for international students to pursue higher education in Japan.

Japan is home to an array of technological innovations with a mix of traditional cultures, making it an attractive choice for higher education.

Although it’s not well known, many universities in Japan offer programs for international students. These programs are available primarily in English but also offer students a chance to learn the Japanese language and customs. We do have an article about English university education in and around Tokyo .

Japanese universities offer programs for Bachelor’s, Master’s, and Doctorate degrees in many different areas of study.

Why Study in Japan?

Japan has held a strong reputation for being the center of technology and innovation for quite some time, which is well reflected in its universities.

International experience also gives applicants a competitive edge over their competition. More employers value international experience as it shows drive and willingness to experiment. If your end goal is to work in Japan, starting as an international student allows you the chance to build a professional network.

Despite Japan’s reputation as a monolithic culture, many opportunities exist for non-Japanese students to study for higher education in Japan. The reputation of Japanese universities is well reflected at each institution, so any program you choose will be well worth your time.

Conclusion About the Education System in Japan

Education in Japan may seem a little different compared to your own culture. However, there’s no need to be alarmed about the quality of education, as Japan is often cited for having a 99% literacy rate .

Despite its emphasis on testing, the Japanese education system has been successful. Its strong educational and societal values are admired worldwide and produce some of the most talented students.

Moreover, for higher education, Japan offers a good mix of traditional and modern university programs that testify to its rich academic history and innovative future.

These programs provide top-notch education and a unique opportunity for foreigners to immerse themselves in the Japanese culture and way of life.

Pursuing higher education in Japan can be a transformative experience, bridging gaps between the East and the West. Japanese universities are a compelling destination for those seeking an academic adventure filled with learning, discovery, and personal growth.

Furthermore, Japan is a good destination for higher education if you wish to take advantage of its career growth prospects. With a continuously increasing demand-supply of talent because of its aging and declining population, Japan is a good destination for career growth prospects. Having a college education in Japan helps in achieving that goal more efficiently.

Jamila Brown is a 5-year veteran in Japan working in the education and business sector. Jamila is currently transitioning into the digital marketing world in Japan. In her free time, she enjoys traveling and writing about the culture in Japan.

- Japan Corner

- A Kanji a Day (69)

- Japanese Culture and Art (16)

- Working in Japan (14)

- Life in Japan (12)

- Travel in Japan (9)

- Japan Visa (7)

- Japanese Language & Communication (6)

- Housing in Japan (6)

- Medical care in Japan (3)

- Foreigners in Japan (2)

- Education in Japan (2)

- Tech Corner

- AI/ML and Deep Learning (25)

- Application Development and Testing (11)

- Methodologies (9)

- Tech Interviews Questions (8)

- Blockchain (8)

- IT Security (3)

- Cloud Computing (3)

- Automation (2)

- Miscellaneous (2)

Jobs & Career Corner

- Jobs and Career Corner

Let us know about your question or problem and we will reach out to you.

Employment Japan

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Become Our Business Partners

- Jobs & Career

For Employers

EJable.com 806, 2-7-4, Aomi, Koto-ku, Tokyo, 135-0064, Japan

Send to a friend

- Society ›

- Education & Science

Education in Japan - statistics & facts

school system in japan, psychological pressure on children and long-term absentees from school, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Number of educational institutions Japan 2023, by type

Enrollment rate in school education Japan AY 2023, by institution type

Annual budget of MEXT Japan FY 2015-2024

Editor’s Picks Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Educational Institutions & Market

Number of students at primary and secondary schools Japan 2023, by type

Education Level & Skills

Recommended statistics

- Premium Statistic Number of educational institutions Japan 2023, by type

- Premium Statistic Enrollment rate in school education Japan AY 2023, by institution type

- Premium Statistic Number of students in school education in Japan in 2023, by prefecture

- Premium Statistic Number of male students Japan 2023, by institution type

- Premium Statistic Number of female students Japan 2023, by institution type

- Premium Statistic Number of full-time teachers Japan 2023, by institution type

- Premium Statistic Sales of school education facilities Japan 2023, by institution type

Number of educational institutions in Japan in 2023, by type

Enrollment rate in school education in Japan in academic year 2023, by institution type

Number of students in school education in Japan in 2023, by prefecture

Number of students enrolled in educational institutions in Japan in 2023, by prefecture (in 1,000s)

Number of male students Japan 2023, by institution type

Number of male students in educational institutions in Japan in 2023, by institution type (in 1,000s)

Number of female students Japan 2023, by institution type

Number of female students in educational institutions in Japan in 2023, by institution type (in 1,000s)

Number of full-time teachers Japan 2023, by institution type

Number of full-time teachers in educational institutions in Japan in 2023, by institution type (in 1,000s)

Sales of school education facilities Japan 2023, by institution type

Sales of school education facilities in Japan in 2023, by institution type (in billion Japanese yen)

Primary and secondary schools

- Premium Statistic Number of kindergartens Japan 2014-2023, by type

- Premium Statistic Number of elementary schools Japan 2014-2023, by type

- Premium Statistic Number of junior high/middle schools Japan 2014-2023, by type

- Premium Statistic Number of senior high schools Japan 2014-2023, by type

- Premium Statistic Number of special education schools Japan 2014-2023, by type

Number of kindergartens Japan 2014-2023, by type

Number of national, public, and private kindergartens in Japan from 2014 to 2023

Number of elementary schools Japan 2014-2023, by type

Number of national, public, and private elementary schools in Japan from 2014 to 2023

Number of junior high/middle schools Japan 2014-2023, by type

Number of national, public, and private lower secondary schools in Japan from 2014 to 2023

Number of senior high schools Japan 2014-2023, by type

Number of national, public, and private upper secondary schools in Japan from 2014 to 2023

Number of special education schools Japan 2014-2023, by type

Number of national, public, and private special needs education schools in Japan from 2014 to 2023

Students at primary and secondary schools

- Premium Statistic Number of students at primary and secondary schools Japan 2004-2023

- Premium Statistic Number of students at primary and secondary schools Japan 2023, by type

- Premium Statistic Correct answer rate of NAAA Japan 2024, by subject

- Premium Statistic Ratio of senior high school students with A2 English level Japan AY 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Mean PISA score of students in Japan 2000-2022, by subject

Number of students at primary and secondary schools Japan 2004-2023

Number of students enrolled in primary and secondary schools in Japan from 2004 to 2023 (in 1,000s)

Number of students attending primary and secondary schools in Japan in 2023, by institution type

Correct answer rate of NAAA Japan 2024, by subject

Average rate of correct answers of students taking the National Assessment Academic Ability (NAAA) in Japan in 2024, by subject

Ratio of senior high school students with A2 English level Japan AY 2014-2023

Ratio of public senior high students who attained A2 English level based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) in Japan from academic year 2014 to 2023

Mean PISA score of students in Japan 2000-2022, by subject

Mean Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) score of students in Japan from 2000 to 2022, by subject

Long-term absentees

- Premium Statistic Number of long-term absentees at primary and secondary schools Japan AY 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Ratio of absentees at primary and secondary schools Japan AY 2022, by reason

- Premium Statistic Distribution of absentees at primary and secondary schools Japan AY 2022, by cause

- Premium Statistic Number of reported bullying cases among pupils in Japan AY 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of bullied pupils in Japan AY 2022, by school grade

Number of long-term absentees at primary and secondary schools Japan AY 2013-2022

Number of students who are absent for a long time from primary and lower secondary schools in Japan from academic year 2013 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Ratio of absentees at primary and secondary schools Japan AY 2022, by reason

Ratio of long-term absentees to total number of students at primary and lower secondary schools in Japan in academic year 2022, by reason

Distribution of absentees at primary and secondary schools Japan AY 2022, by cause

Distribution of students who were absent for a long time from primary and lower secondary schools in Japan in academic year 2022, by main cause

Number of reported bullying cases among pupils in Japan AY 2013-2022

Total number of reported bullying incidents among students in Japan from academic year 2013 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of bullied pupils in Japan AY 2022, by school grade

Number of bullied students in Japan in academic year 2022, by school year (in 1,000s)

Tertiary education

- Premium Statistic Number of universities Japan 2014-2023, by type

- Premium Statistic Number of graduate schools Japan 2014-2023, by type

- Premium Statistic Number of junior colleges Japan 2014-2023, by type

- Premium Statistic Number of students at higher education institutions Japan 2023, by type

- Premium Statistic Number of university students Japan 2014-2023

Number of universities Japan 2014-2023, by type

Number of national, public, and private universities in Japan from 2014 to 2023

Number of graduate schools Japan 2014-2023, by type

Number of national, public, and private graduate schools in Japan from 2014 to 2023

Number of junior colleges Japan 2014-2023, by type

Number of public and private junior colleges in Japan from 2014 to 2023

Number of students at higher education institutions Japan 2023, by type

Number of students attending higher education institutions in Japan in 2023, by institution type

Number of university students Japan 2014-2023

Number of students enrolled at universities in Japan from 2014 to 2023 (in millions)

Other institutions for learning

- Premium Statistic Number of out-of-school learning facilities Japan 2023, by institution type

- Premium Statistic Sales of out-of-school learning facilities Japan 2023, by institution type

- Premium Statistic Number of businesses of foreign language conversation schools Japan FY 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Number of lifelong learning centers Japan 2008-2021

Number of out-of-school learning facilities Japan 2023, by institution type

Number of out-of-school educational facilities in Japan in 2023, by institution type

Sales of out-of-school learning facilities Japan 2023, by institution type

Sales revenue of out-of-school educational facilities in Japan in 2023, by institution type (in billion Japanese yen)

Number of businesses of foreign language conversation schools Japan FY 2014-2023

Number of business establishments of foreign language conversation schools in Japan from fiscal year 2014 to 2023

Number of lifelong learning centers Japan 2008-2021

Number of lifelong learning centers in Japan from 2008 to 2021

Governmental budget and expenditure

- Premium Statistic Annual budget of MEXT Japan FY 2015-2024

- Premium Statistic Share of annual budget of MEXT Japan FY 2024, by category

- Premium Statistic Local government expenditures on education Japan FY 2013-2022

Annual budget of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) in Japan from fiscal year 2015 to 2024 (in trillion Japanese yen)

Share of annual budget of MEXT Japan FY 2024, by category

Share of annual budget of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) in Japan in fiscal year 2024, by category

Local government expenditures on education Japan FY 2013-2022

Local governments' expenditure on education in Japan from fiscal year 2013 to 2022 (in trillion Japanese yen)

Household expenditure

- Premium Statistic Annual expenses for education per household Japan 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Annual expenses for school fee per household Japan 2023, type of institution

- Premium Statistic Annual expenses for tutorial fees per household Japan 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Annual expenses for tutorial fees per household Japan 2023, by purpose

Annual expenses for education per household Japan 2014-2023

Average annual expenditure on education per household in Japan from 2014 to 2023 (in 1,000 Japanese yen)

Annual expenses for school fee per household Japan 2023, type of institution

Average annual expenditure on school fees per household in Japan in 2023, type of institution (in Japanese yen)

Annual expenses for tutorial fees per household Japan 2014-2023

Average annual expenditure on tutorial fees per household in Japan from 2014 to 2023 (in 1,000 Japanese yen)

Annual expenses for tutorial fees per household Japan 2023, by purpose

Average annual expenditure on supplementary tutorial fees per household in Japan in 2023, by purpose (in Japanese yen)

Further reports

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

- Languages ›

The Japanese Education System

urbancow / Getty Images

- History & Culture

- Essential Japanese Vocabulary

- Japanese Grammar

- B.A., Kwansei Gakuin University

The Japanese educational system was reformed after World War II. The old 6-5-3-3 system was changed to a 6-3-3-4 system (6 years of elementary school, 3 years of junior high school, 3 years of senior high school and 4 years of University) with reference to the American system . The gimukyoiku 義務教育 (compulsory education) time period is 9 years, 6 in shougakkou 小学校 (elementary school) and 3 in chuugakkou 中学校 (junior high school).

Japan has one of the world's best-educated populations, with 100% enrollment in compulsory grades and zero illiteracy . While not compulsory, high school (koukou 高校) enrollment is over 96% nationwide and nearly 100% in the cities. The high school drop out rate is about 2% and has been increasing. About 46% of all high school graduates go on to university or junior college.

The Ministry of Education closely supervises curriculum, textbooks, and classes and maintains a uniform level of education throughout the country. As a result, a high standard of education is possible.

Student Life

Most schools operate on a three-term system with the new year starting in April. The modern educational system started in 1872 and is modeled after the French school system, which begins in April. The fiscal year in Japan also begins in April and ends in March of the following year, which is more convenient in many aspects.

April is the height of spring when cherry blossoms (the most loved flower of the Japanese!) bloom and the most suitable time for a new start in Japan. This difference in the school-year system causes some inconvenience to students who wish to study abroad in the U.S. A half-year is wasted waiting to get in and often another year is wasted when coming back to the Japanese university system and having to repeat a year.

Except for the lower grades of elementary school, the average school day on weekdays is 6 hours, which makes it one of the longest school days in the world. Even after school lets out, the children have drills and other homework to keep them busy. Vacations are 6 weeks in the summer and about 2 weeks each for winter and spring breaks. There is often homework over these vacations.

Every class has its own fixed classroom where its students take all the courses, except for practical training and laboratory work. During elementary education, in most cases, one teacher teaches all the subjects in each class. As a result of the rapid population growth after World War II, the numbers of students in a typical elementary or junior high school class once exceeded 50 students, but now it is kept under 40. At public elementary and junior high school, school lunch (kyuushoku 給食) is provided on a standardized menu, and it is eaten in the classroom. Nearly all junior high schools require their students to wear a school uniform (seifuku 制服).

A big difference between the Japanese school system and the American School system is that Americans respect individuality while the Japanese control the individual by observing group rules. This helps to explain the Japanese characteristic of group behavior.

Translation Exercise

- Because of the rapid population growth after World War II, the number of students in a typical elementary or junior high school once exceeded 50.

- Dainiji sekai taisen no ato no kyuugekina jinkou zouka no tame, tenkeitekina shou-chuu gakkou no seitosu wa katsute go-juu nin o koemashita.

- 第二次世界大戦のあとの急激な人口増加のため、典型的な小中学校の生徒数はかつて50人を超えました。

"~no tame" means "because of ~".

- I didn't go to work because of a cold.

- Kaze no tame, shigoto ni ikimasen deshita.

- 風邪のため、仕事に行きませんでした。

- Japanese Writing for Beginners

- Learn Basic Counting and Numbers in Japanese

- Telling Time in Japanese

- How To Stress Syllables in Japanese Pronunciation

- 100 of the Most Common Kanji Characters

- Hiragana Lessons - Stroke Guide to は、ひ、ふ、へ、ほ (Ha, Hi, Fu, He, Ho)

- Hiragana Lessons - Stroke Guide to な、に、ぬ、ね、の (Na, Ni, Nu, Ne, No)

- Translation and Characters of the Japanese Word "Atari"

- Learn the Japanese Phrase 'Ki o Tsukete'

- The Ko-So-A-Do System

- Making the Right Strokes for さ, し, す, せ, そ (Sa, Shi, Su, Se, So)

- Be Able to Write か、き、く、け、こ With These Helpful Stroke-By-Stroke Guides

- Should Japanese Writing Be Horizontal or Vertical?

- Japanese Greetings and Parting Phrases

- A Hiragana Stroke Guide to あ、い、う、え、お (A, I, U, E, O)

- What Does the Japanese Word "Mata" Mean?

Stanford University

SPICE is a program of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

Japanese Education

Japanese Educational Achievements

Japanese K-12 Education

Japanese Higher Education

Contemporary Educational Issues

Significant Comparative Education Topics

It is important for teachers and students to develop a broad understanding of Japanese education. Americans who are knowledgeable of teaching and learning in Japan gain insights about a different culture and are better able to clearly think about their own educational system. This Digest is an introductory overview of 1) Japanese educational achievements, 2) Japanese K-12 education, 3) Japanese higher education, 4) contemporary educational issues, and 5) significant U.S.-Japan comparative education topics.

Japanese Educational Achievements .

Japan's greatest educational achievement is the high-quality basic education most young people receive by the time they complete high school. Although scores have slightly declined in recent years, Japanese students consistently rank among world leaders in international mathematics tests. Recent statistics indicate that well over 95 percent of Japanese are literate, which is particularly impressive since the Japanese language is one of the world's most difficult languages to read and write. Currently over 95 percent of Japanese high school students graduate compared to 89 percent of American students. Some Japanese education specialists estimate that the average Japanese high school graduate has attained about the same level of education as the average American after two years of college. Comparable percentages of Japanese and American high school graduates now go on to some type of post-secondary institution.

Japanese K-12 Education.

Even though the Japanese adopted the American 6-3-3 model during the U.S. Occupation after World War II, elementary and secondary education is more centralized than in the United States. Control over curriculum rests largely with the national Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology ( Monbukagakusho)

and education is compulsory through the ninth grade. Municipalities and private sources fund kindergartens, but national, prefectural, and local governments pay almost equal shares of educational costs for students in grades one through nine. Almost 90 percent of students attend public schools through the ninth grade, but over 29 percent of students go to private high schools. The percentage of national funding for high schools is quite low, with prefectures and municipalities assuming most of the costs for public high schools. High salaries, relatively high prestige, and low birth rates make teaching jobs quite difficult to obtain in Japan while in the United States there are teacher shortages in certain fields. Although more Japanese schools are acquiring specialists such as special education teachers and counselors, American schools have many more special subjects and support personnel than is the case in Japan. Japanese schools have only two or three administrators, one of whom has some teaching responsibilities.

Japanese students spend at least six weeks longer in school each year than their American counterparts although Japan's school year was recently shortened when all required half-day Saturday public school attendance ended in 2002.

While the Japanese K-12 curriculum is actually quite similar in many respects to the curriculum of U.S. schools, there are important differences. Because Japanese teachers at all levels are better prepared in mathematics than their American counterparts, instruction in that subject is more sophisticated in Japan. Japanese language instruction receives more attention in Japanese schools than English instruction in the United States because of the difficulty of learning written Japanese. Virtually every Japanese student takes English language courses from the seventh grade through the final year of high school.

Since many Japan Digest readers are social studies teachers, a few words about those subjects are included here. First- and second-grade students study social studies in an integrated science/social studies course. In grades 3-12, there are separate civics, geography, Japanese and world history, sociology, and politics-economics courses. University-bound students may elect to take more or less social studies electives depending upon their career interests.

All Japanese texts are written and produced in the private sector; however, the texts must be approved by the Ministry of Education. Textbook content, length, and classroom utilization in Japan is quite different than in the United States. The content of Japanese textbooks is based upon the national curriculum, while most American texts tend to cover a wider array of topics. Japanese textbooks typically contain about half the pages of their American counterparts. Consequently, unlike many American teachers, almost all Japanese teachers finish their textbooks in an academic year.

The Japanese believe schools should teach not only academic skills but good character traits as well. While a small amount of hours every year is devoted to moral education in the national curriculum, there is substantial anecdotal evidence that teachers do not take the instructional time too seriously and often use it for other purposes. Still, Japanese teachers endeavor to inculcate good character traits in students through the hidden curriculum. For example, all Japanese students and teachers clean school buildings every week. Japanese students are constantly exhorted by teachers to practice widely admired societal traits such as putting forth intense effort on any task and responding to greetings from teachers in a lively manner.

Many American public high schools are comprehensive. While there are a few comprehensive high schools in Japan, they are not popular. Between 75 and 80 percent of all Japanese students enroll in university preparation tracks. Most university-bound students attend separate academic high schools while students who definitely do not plan on higher education attend separate commercial or industrial high schools. In the United States, students enter secondary schools based on either school district assignment or personal choice. In Japan almost all students are admitted to high school based upon entrance examination performance. Since entering a high-ranked high school increases a student's chance of university admission or of obtaining a good job after high school graduation, over half of Japanese junior high students attend private cram schools, or juku, to supplement their examination preparations. Until recently examination performance was the major criterion for university entrance as well. However many private colleges and universities have replaced entrance examinations with other methods for determining admission, including interviews. Although mid- and high-level universities still rely primarily on entrance examination scores, increasing numbers of college-bound students do not spend enormous amounts of hours studying for university examinations as was the case until just a few years ago.

Japanese Higher Education.

Japan, with almost three million men and women enrolled in over 700 universities and four-year colleges, has the second largest higher educational system in the developed world. In Japan, public universities usually enjoy more prestige than their private counterparts and only about 27 percent of all university-bound students manage to gain admission to public universities. Even so, Japanese universities are considered to be the weakest component in the nation's educational system. Many Japanese students have traditionally considered their university time to be more social than academic and, usually, professors demand relatively little of their charges. Until recently, graduate education in Japan was underdeveloped compared to Europe and the United States. However in response to increased demands for graduate education because of globalization, Japanese graduate enrollments have increased by approximately one third since the mid-1990s.

Contemporary Educational Issues.

In the past decade a variety of factors have contributed both to changes in Japanese schools and to increasing controversy about education. Japanese annual birth rates have been decreasing for almost two decades, and Japan's current population of almost 128 million is expected to decline. Almost half of all Japanese women with children in school now work outside the home at some point during their children's schooling. Although low compared to the U.S., Japan's divorce rates have been rising recently. While Japanese teachers now enjoy considerably smaller classes than at any time in the past, they face increasing discipline problems resulting in part from children who do not get adequate parental attention. Also Japan's economy has experienced a fifteen-year malaise, and many people believe that an inflexible educational system is in part responsible for the country's economic problems.

In 2002 the Ministry of Education began to implement educational reforms that officials labeled the most significant since the end of World War II. In an attempt to stimulate students to be independent and self-directed learners, one third of the content of the national curriculum was eliminated. Japanese students in grades 3-9 are now required to take Integrated Studies classes in which they and their teachers jointly plan projects, field trips, and other "hands-on" activities. Students in Integrated Studies learn about their local environment, history, and economy. They also engage in regular interactions with foreigners, and in learning conversational English. There are no Integrated Studies textbooks, and teachers are not allowed to give tests on what students have learned. Although many elementary school teachers and students seem to enjoy Integrated Studies, the reform is quite controversial among both the public and junior high school educators. They perceive Integrated Studies as "dumbing down" the national curriculum, and they are concerned that the reform will result in less-educated students and lower high school entrance examination performance. In response to this controversy, the Ministry of Education has recently announced plans to reevaluate Integrated Studies.

Japanese higher education is also currently going through significant changes. During the early part of the 21st century, the Japanese government initiated policies intended to expand educational opportunities in professions such as business and law. In 2004 the Japanese government declared the national universities to be "independent administrative entities," with the goal of creating more autonomous universities offering less duplication of programs while having more financial discretion. It is expected that some national universities will attain international reputations as research centers. It is quite likely that the recent reforms will also result in downsizing of some public universities and expansion of other public institutions of higher learning. Because of projected smaller enrollments in a few years due to continuing birth rate declines, many of Japan's private universities are potential "endangered species."

The way certain Japanese textbooks depict World War II has twice been the subject of international controversy in the new century. In 2001 the Ministry of Education approved a new junior high school textbook, written and edited by a group of nationalist academics, that omitted topics such as the Japanese army's mistreatment of women in battle zones and areas under Japanese rule and the Nanjing Massacre (Masalski 2001). In Spring 2005 the Ministry approved a new edition of the same textbook. In both instances, despite the fact that less than 1% of all Japanese students use the book in schools, there were widespread Chinese and Korean protests. In 2005 the situation negatively affected overall Chinese-Japanese relations, as boycotts of Japanese goods occurred and some Japanese-owned property was destroyed in China.

Significant Comparative Education Topics.

Despite the problems addressed in this Digest, American policymakers and educators will find Japan's educational system, and in particular its K-12 schools, worthy of serious study. Scholars of Japanese education are particularly interested in the following questions: Why are Japanese elementary teachers so much more successful than their American counterparts in teaching math? How have Japanese educators managed to sustain successful peer collaboration for decades? How is moral education handled in Japan, and can American textbooks be improved through a closer examination of slimmer and more focused Japanese texts? In an era of increasing globalization, it is imperative that American educators study other nations' schools. Japan offers rich food for thought for all those who wish to improve the teaching profession.

Masalski, Kathleen. (2001). " Examining the Japanese History Textbook Controversies." A Japan Digest produced by the National Clearinghouse for U.S.-Japan Studies. Full text at http://www.indiana.edu/~japan/Digests/textbook.html .

Bibliography

Benjamin, Gail. Japanese Lessons: A Year in a Japanese School through the Eyes of an American Anthropologist and Her Children. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

DeCoker, Gary, editor. National Standards and School Reform in Japan and the United States. New York: Teachers College Press, 2002.

Ellington, Lucien. "Beyond the Rhetoric: Essential Questions about Japanese Education." Footnotes, December 2003. Foreign Policy Research Institute's website: http://www.fpri.org

Eades, J.S. et al, editors. The 'Big Bang' in Japanese Higher Education: The 2004 Reforms and the Dynamics of Change. Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press, 2005.

Fukuzawa, Rebecca Erwin and Gerald K. Letendre. Intense Years: How Japanese Adolescents Balance School, Family, and Friends. New York: Routledge Falmer, 2000.

Goodman, Roger and David Phillips, editors. Can the Japanese Change Their Education System? Oxford: Symposium Books, 2003.

Guo, Yugui. Asia's Educational Edge: Current Achievements in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, and India. New York: Lexington Books, 2005.

Letendre, Gerald K. Learning to Be Adolescent: Growing Up in U.S. and Japanese Middle Schools. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Wray, Harry. Japanese and American Education: Attitudes and Practices. Westport, Conn.: Bergin and Garvey, 1999.

Lucien Ellington is UC Foundation Professor of Education at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. Ellington is also Co-director of the UTC Asia Project and Editor of Education About Asia .

IMAGES

VIDEO