The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing

- How Nurses Use Critical Thinking

- How to Improve Critical Thinking

- Common Mistakes

Some experts describe a person’s ability to question belief systems, test previously held assumptions, and recognize ambiguity as evidence of critical thinking. Others identify specific skills that demonstrate critical thinking, such as the ability to identify problems and biases, infer and draw conclusions, and determine the relevance of information to a situation.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN, has been a critical care nurse for 10 years in neurological trauma nursing and cardiovascular and surgical intensive care. He defines critical thinking as “necessary for problem-solving and decision-making by healthcare providers. It is a process where people use a logical process to gather information and take purposeful action based on their evaluation.”

“This cognitive process is vital for excellent patient outcomes because it requires that nurses make clinical decisions utilizing a variety of different lenses, such as fairness, ethics, and evidence-based practice,” he says.

How Do Nurses Use Critical Thinking?

Successful nurses think beyond their assigned tasks to deliver excellent care for their patients. For example, a nurse might be tasked with changing a wound dressing, delivering medications, and monitoring vital signs during a shift. However, it requires critical thinking skills to understand how a difference in the wound may affect blood pressure and temperature and when those changes may require immediate medical intervention.

Nurses care for many patients during their shifts. Strong critical thinking skills are crucial when juggling various tasks so patient safety and care are not compromised.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN, is a nurse educator with a clinical background in surgical-trauma adult critical care, where critical thinking and action were essential to the safety of her patients. She talks about examples of critical thinking in a healthcare environment, saying:

“Nurses must also critically think to determine which patient to see first, which medications to pass first, and the order in which to organize their day caring for patients. Patient conditions and environments are continually in flux, therefore nurses must constantly be evaluating and re-evaluating information they gather (assess) to keep their patients safe.”

The COVID-19 pandemic created hospital care situations where critical thinking was essential. It was expected of the nurses on the general floor and in intensive care units. Crystal Slaughter is an advanced practice nurse in the intensive care unit (ICU) and a nurse educator. She observed critical thinking throughout the pandemic as she watched intensive care nurses test the boundaries of previously held beliefs and master providing excellent care while preserving resources.

“Nurses are at the patient’s bedside and are often the first ones to detect issues. Then, the nurse needs to gather the appropriate subjective and objective data from the patient in order to frame a concise problem statement or question for the physician or advanced practice provider,” she explains.

Top 5 Ways Nurses Can Improve Critical Thinking Skills

We asked our experts for the top five strategies nurses can use to purposefully improve their critical thinking skills.

Case-Based Approach

Slaughter is a fan of the case-based approach to learning critical thinking skills.

In much the same way a detective would approach a mystery, she mentors her students to ask questions about the situation that help determine the information they have and the information they need. “What is going on? What information am I missing? Can I get that information? What does that information mean for the patient? How quickly do I need to act?”

Consider forming a group and working with a mentor who can guide you through case studies. This provides you with a learner-centered environment in which you can analyze data to reach conclusions and develop communication, analytical, and collaborative skills with your colleagues.

Practice Self-Reflection

Rhoads is an advocate for self-reflection. “Nurses should reflect upon what went well or did not go well in their workday and identify areas of improvement or situations in which they should have reached out for help.” Self-reflection is a form of personal analysis to observe and evaluate situations and how you responded.

This gives you the opportunity to discover mistakes you may have made and to establish new behavior patterns that may help you make better decisions. You likely already do this. For example, after a disagreement or contentious meeting, you may go over the conversation in your head and think about ways you could have responded.

It’s important to go through the decisions you made during your day and determine if you should have gotten more information before acting or if you could have asked better questions.

During self-reflection, you may try thinking about the problem in reverse. This may not give you an immediate answer, but can help you see the situation with fresh eyes and a new perspective. How would the outcome of the day be different if you planned the dressing change in reverse with the assumption you would find a wound infection? How does this information change your plan for the next dressing change?

Develop a Questioning Mind

McGowan has learned that “critical thinking is a self-driven process. It isn’t something that can simply be taught. Rather, it is something that you practice and cultivate with experience. To develop critical thinking skills, you have to be curious and inquisitive.”

To gain critical thinking skills, you must undergo a purposeful process of learning strategies and using them consistently so they become a habit. One of those strategies is developing a questioning mind. Meaningful questions lead to useful answers and are at the core of critical thinking .

However, learning to ask insightful questions is a skill you must develop. Faced with staff and nursing shortages , declining patient conditions, and a rising number of tasks to be completed, it may be difficult to do more than finish the task in front of you. Yet, questions drive active learning and train your brain to see the world differently and take nothing for granted.

It is easier to practice questioning in a non-stressful, quiet environment until it becomes a habit. Then, in the moment when your patient’s care depends on your ability to ask the right questions, you can be ready to rise to the occasion.

Practice Self-Awareness in the Moment

Critical thinking in nursing requires self-awareness and being present in the moment. During a hectic shift, it is easy to lose focus as you struggle to finish every task needed for your patients. Passing medication, changing dressings, and hanging intravenous lines all while trying to assess your patient’s mental and emotional status can affect your focus and how you manage stress as a nurse .

Staying present helps you to be proactive in your thinking and anticipate what might happen, such as bringing extra lubricant for a catheterization or extra gloves for a dressing change.

By staying present, you are also better able to practice active listening. This raises your assessment skills and gives you more information as a basis for your interventions and decisions.

Use a Process

As you are developing critical thinking skills, it can be helpful to use a process. For example:

- Ask questions.

- Gather information.

- Implement a strategy.

- Evaluate the results.

- Consider another point of view.

These are the fundamental steps of the nursing process (assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate). The last step will help you overcome one of the common problems of critical thinking in nursing — personal bias.

Common Critical Thinking Pitfalls in Nursing

Your brain uses a set of processes to make inferences about what’s happening around you. In some cases, your unreliable biases can lead you down the wrong path. McGowan places personal biases at the top of his list of common pitfalls to critical thinking in nursing.

“We all form biases based on our own experiences. However, nurses have to learn to separate their own biases from each patient encounter to avoid making false assumptions that may interfere with their care,” he says. Successful critical thinkers accept they have personal biases and learn to look out for them. Awareness of your biases is the first step to understanding if your personal bias is contributing to the wrong decision.

New nurses may be overwhelmed by the transition from academics to clinical practice, leading to a task-oriented mindset and a common new nurse mistake ; this conflicts with critical thinking skills.

“Consider a patient whose blood pressure is low but who also needs to take a blood pressure medication at a scheduled time. A task-oriented nurse may provide the medication without regard for the patient’s blood pressure because medication administration is a task that must be completed,” Slaughter says. “A nurse employing critical thinking skills would address the low blood pressure, review the patient’s blood pressure history and trends, and potentially call the physician to discuss whether medication should be withheld.”

Fear and pride may also stand in the way of developing critical thinking skills. Your belief system and worldview provide comfort and guidance, but this can impede your judgment when you are faced with an individual whose belief system or cultural practices are not the same as yours. Fear or pride may prevent you from pursuing a line of questioning that would benefit the patient. Nurses with strong critical thinking skills exhibit:

- Learn from their mistakes and the mistakes of other nurses

- Look forward to integrating changes that improve patient care

- Treat each patient interaction as a part of a whole

- Evaluate new events based on past knowledge and adjust decision-making as needed

- Solve problems with their colleagues

- Are self-confident

- Acknowledge biases and seek to ensure these do not impact patient care

An Essential Skill for All Nurses

Critical thinking in nursing protects patient health and contributes to professional development and career advancement. Administrative and clinical nursing leaders are required to have strong critical thinking skills to be successful in their positions.

By using the strategies in this guide during your daily life and in your nursing role, you can intentionally improve your critical thinking abilities and be rewarded with better patient outcomes and potential career advancement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Critical Thinking in Nursing

How are critical thinking skills utilized in nursing practice.

Nursing practice utilizes critical thinking skills to provide the best care for patients. Often, the patient’s cause of pain or health issue is not immediately clear. Nursing professionals need to use their knowledge to determine what might be causing distress, collect vital information, and make quick decisions on how best to handle the situation.

How does nursing school develop critical thinking skills?

Nursing school gives students the knowledge professional nurses use to make important healthcare decisions for their patients. Students learn about diseases, anatomy, and physiology, and how to improve the patient’s overall well-being. Learners also participate in supervised clinical experiences, where they practice using their critical thinking skills to make decisions in professional settings.

Do only nurse managers use critical thinking?

Nurse managers certainly use critical thinking skills in their daily duties. But when working in a health setting, anyone giving care to patients uses their critical thinking skills. Everyone — including licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced nurse practitioners —needs to flex their critical thinking skills to make potentially life-saving decisions.

Meet Our Contributors

Crystal Slaughter is a core faculty member in Walden University’s RN-to-BSN program. She has worked as an advanced practice registered nurse with an intensivist/pulmonary service to provide care to hospitalized ICU patients and in inpatient palliative care. Slaughter’s clinical interests lie in nursing education and evidence-based practice initiatives to promote improving patient care.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads is a nurse educator and freelance author and editor. She earned a BSN from Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing and an MS in nursing education from Northern Illinois University. Rhoads earned a Ph.D. in education with a concentration in nursing education from Capella University where she researched the moderation effects of emotional intelligence on the relationship of stress and GPA in military veteran nursing students. Her clinical background includes surgical-trauma adult critical care, interventional radiology procedures, and conscious sedation in adult and pediatric populations.

Nicholas McGowan is a critical care nurse with 10 years of experience in cardiovascular, surgical intensive care, and neurological trauma nursing. McGowan also has a background in education, leadership, and public speaking. He is an online learner who builds on his foundation of critical care nursing, which he uses directly at the bedside where he still practices. In addition, McGowan hosts an online course at Critical Care Academy where he helps nurses achieve critical care (CCRN) certification.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing? (With Examples, Importance, & How to Improve)

Successful nursing requires learning several skills used to communicate with patients, families, and healthcare teams. One of the most essential skills nurses must develop is the ability to demonstrate critical thinking. If you are a nurse, perhaps you have asked if there is a way to know how to improve critical thinking in nursing? As you read this article, you will learn what critical thinking in nursing is and why it is important. You will also find 18 simple tips to improve critical thinking in nursing and sample scenarios about how to apply critical thinking in your nursing career.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

4 reasons why critical thinking is so important in nursing, 1. critical thinking skills will help you anticipate and understand changes in your patient’s condition., 2. with strong critical thinking skills, you can make decisions about patient care that is most favorable for the patient and intended outcomes., 3. strong critical thinking skills in nursing can contribute to innovative improvements and professional development., 4. critical thinking skills in nursing contribute to rational decision-making, which improves patient outcomes., what are the 8 important attributes of excellent critical thinking in nursing, 1. the ability to interpret information:, 2. independent thought:, 3. impartiality:, 4. intuition:, 5. problem solving:, 6. flexibility:, 7. perseverance:, 8. integrity:, examples of poor critical thinking vs excellent critical thinking in nursing, 1. scenario: patient/caregiver interactions, poor critical thinking:, excellent critical thinking:, 2. scenario: improving patient care quality, 3. scenario: interdisciplinary collaboration, 4. scenario: precepting nursing students and other nurses, how to improve critical thinking in nursing, 1. demonstrate open-mindedness., 2. practice self-awareness., 3. avoid judgment., 4. eliminate personal biases., 5. do not be afraid to ask questions., 6. find an experienced mentor., 7. join professional nursing organizations., 8. establish a routine of self-reflection., 9. utilize the chain of command., 10. determine the significance of data and decide if it is sufficient for decision-making., 11. volunteer for leadership positions or opportunities., 12. use previous facts and experiences to help develop stronger critical thinking skills in nursing., 13. establish priorities., 14. trust your knowledge and be confident in your abilities., 15. be curious about everything., 16. practice fair-mindedness., 17. learn the value of intellectual humility., 18. never stop learning., 4 consequences of poor critical thinking in nursing, 1. the most significant risk associated with poor critical thinking in nursing is inadequate patient care., 2. failure to recognize changes in patient status:, 3. lack of effective critical thinking in nursing can impact the cost of healthcare., 4. lack of critical thinking skills in nursing can cause a breakdown in communication within the interdisciplinary team., useful resources to improve critical thinking in nursing, youtube videos, my final thoughts, frequently asked questions answered by our expert, 1. will lack of critical thinking impact my nursing career, 2. usually, how long does it take for a nurse to improve their critical thinking skills, 3. do all types of nurses require excellent critical thinking skills, 4. how can i assess my critical thinking skills in nursing.

• Ask relevant questions • Justify opinions • Address and evaluate multiple points of view • Explain assumptions and reasons related to your choice of patient care options

5. Can I Be a Nurse If I Cannot Think Critically?

- Practice Test

- Fundamentals of Nursing

- Anatomy and Physiology

- Medical and Surgical Nursing

- Perioperative Nursing

- Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing

- Maternal & Child Nursing

- Community Health Nursing

- Pathophysiology

- Nursing Research

- Study Guide and Strategies

- Nursing Videos

- Work for Us!

- Privacy Policy

- Journals and Essays

Thinking Like a Nurse: The Critical Thinking Skills in the Nursing Practice

Thinking how to nurse is thinking like a nurse. Florence Nightingale (1860) wrote on her notes that women who have charge of the other’s health—to which the application of her integrated experiences must teach herself to think how to nurse, a self-learning acquired from “hints”.

Perhaps, Nightingale referred “hints” as the use of critical thinking skills in patient’s care. The ability to think critically was the foundation of nursing practice started from historic times and is becoming one of the key performance indicators for both students and nursing professionals nowadays.

Educational system continues to evolve and progresses heeding to the needs of the society, and parallel to the changing educational structure and methodology. However, Haber (2020) reported that only 75% of employers claim that the students they hire who underwent 12 or more years of formal education lack of critical thinking and problem-solving abilities despite the progress in the educational system.

What is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking skills, a fundamental skill that plays a pivotal role in our daily survival. In general terms, the skill will not stop in memorization, the process goes beyond connecting the dots from one to concept to another, problem-solving techniques, think creatively, and apply the learned knowledge in new ways (Walden University, 2020). Kaminske (2019), defines critical thinking skills as a domain-specific skill on the ability to solve problems and make effective decisions that require expertise to be applied in a range of situations and scenarios.

In the nursing practice, Critical thinking skill works in assimilation with critical reasoning as a practice-based discipline of decision-making to the health care professionals. Critical thinking is the process of the intentional higher level of thinking to identify patient’s health care needs and appraise evidence-based practice to make choices in the delivery of care.

On the other hand, clinical reasoning as integrated to clinical thinking in application to clinical situation works as a cognitive process to utilized thinking strategies to gather and critically analyze the data concerning the health care needs of the patient, organized the information according to its prioritization, and formulate efficient nursing care plans to improve patient’s outcomes (Berman, et al., 2016).

“Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action”, a precise definition presented by Michael Scriven and Richard Paul at the Eighth Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking and Education Reform during the summer of 1987 (Lakhanigam, 2017).

Lakhanigam added the definition published by the Journal of Nursing Education in 2010 that describes critical thinking as the process involving interpretation and analysis of the problem, reasoning to find a solution, applying, and finally evaluation of the outcomes”. Regis College (2020), emphasized the use of deductive reasoning in observation, analyzing information, formulate conclusions, and performing appropriate actions in a self-directed process .

Theories on the Physiology of Thinking

From the ancient theory of “tabula rasa”, as describes in Wikipedia (2020) that humans are born without built-in mental content, and all knowledge is collected by the brain from experiences and perceptions. In this computer age, a neurologist discovered neurological pathways on how to re-program or reformat our brains like computers by analyzing how the brain appears to process, recognize, remember and transfer information at the level of neural circuits, synapses and neurotransmitters. Willis (2012) discussed the brain’s neuroplastic response to stimulation called neuroplasticity. The information is processed in the reflective and cognitive functions of prefrontal cortex wherein learning incorporated into networks of longterm conceptual memory.

Neuroplasticity is greatly affected by stress, boredom and frustration as seen in the neuroimaging scans of students showed that active metabolic states block the processing in the prefrontal cortex. In response to stress, the amygdala as the switching station became hyperactive resulting to switches of input and output away from the prefrontal cortex down to the control of the lower reactive brain, this response is called fight/flight/freeze (act out/zone out). In this situation, the lower brain’s reactive behaviours are in control. This will result in the loss of information access to the prefrontal cortex and new learning is not retained.

Elseways, Knowles (1984) four principles of andragogy of adult learning included (a.) experiences from mistakes that provide the basis for the learning activities; and (b.) the importance of problems and crisis, as adult learning is problem-centred rather than content-oriented; as well as (c.) involvement in the planning and evaluation of learning; and lastly, (d.) that adults are most interested in a subject that is relevant to their job and personal life.

Learning and thinking as applied in a higher-level context, Ausubel’s assimilation theory may recount the theories on critical thinking. In this theory, Ausubel claimed that learning occurs as a result of the interaction between the acquired learning and the cognitive structure in application to practice (Seel, 2012). Moreover, critical analysis and differentiation of interrelationships between concepts called concept mapping refines the knowledge into a more organized, precise, specific, and integrated learning.

In different circumstances, nursing as a professional working in a toxic environment of the sick, pained, hopeless, weak, and dying patients; bullying, queen bee syndrome, and seniority egoism of colleagues; and backbreaking workloads—have reported cases of work-related boredom and stress. The application of the three theories may improve mentoring-learning strategies in meaningful nursing education and training.

Theories on learning acquisition from the collection of information, physiologic processing on cognitive-reflective functions of the brain, concept mapping, and internal/external utilization of knowledge in application to critical thinking are the frameworks of a skilled critical thinker.

Characteristics of a Skilled Critical-Thinker

Health care system can go a long way, achieving a considerable success having employees that possess the ability to think critically thus decreasing errors in clinical judgments. For this purpose, every nurse is required to obtain the characteristics of an excellent skilled critical thinker.

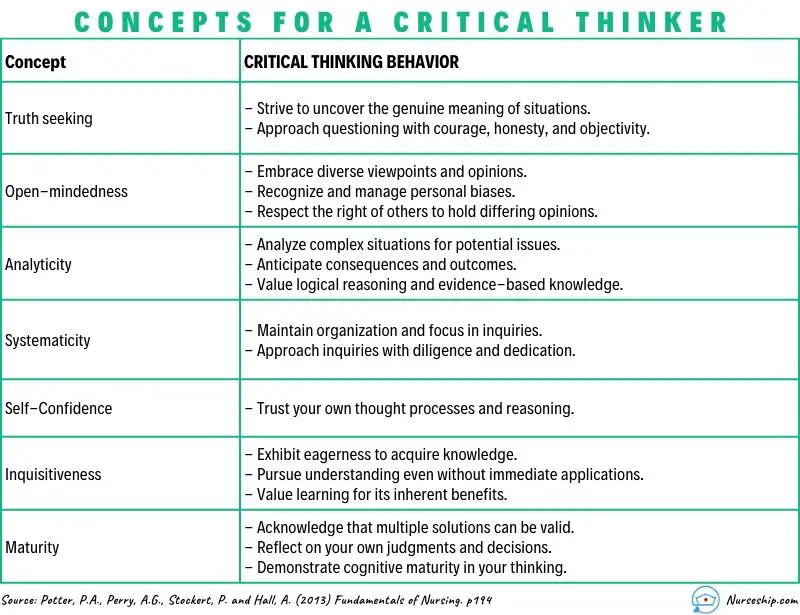

The study of Scheffer and Rubenfeld revealed the common qualities among internationally diverse expert nurses from nine different countries supporting the idea of critical thinking in nursing that encompasses logic and reasoning (Berman, et. Al., 2016), and that includes:

11 Affective Components of a Skilled Critical-Thinker Nurse:

- Perseverance

- Open-mindedness

- Flexibility

- Inquisitiveness

- Intellectual integrity

- Perspective

7 Cognitive Skills of a Skilled Critical-Thinker Nurse:

- Information seeking

- Discriminating

- Transforming knowledge

- Applying standards

- Logical reasoning

Critical Thinking Beyond Exigency and Expediency

Undeniably, nurses with critical thinking ability diversified with effective problem-solving and efficient decision-making skills are the most in-demand and highly valued in the field of the health care industry and academe.

As a nurse striding in the most complicated, stressful and multi-tasking job, you are responsible for making life-changing decisions under the pressure of time and emotions. These reasons as to why critical thinking skills in nursing practice plays a vital role in the care of the patient. Luna (2020), cited seven importance of critical thinking skills in the practice of nursing, such as:

- Nurses’ Critical Thinking Heavily Impacts Patient Care

- It’s Vital to Recognizing Shifts in Patient Status

- It’s Integral to an Honest and Open Exchange of Ideas

- It Allows You to Ensure Patient Safety

- It Helps Nurses Find Quick Fixes and Troubleshooting

- Critical Thinking can Lead to Innovative Improvements

- It Plays a Role in Rational Decision Making

Critical thinking skill is needed in problems identification and implementation of interventions resulting in improved patients outcomes, as well as development in nursing practice by providing new insights on the learned knowledge. Feedback and reflections provide interconnections between nursing research , critical thinking and the nursing practice (Berman, et. Al., 2016).

Critical Thinking Skills: The Mastery, Update and Upgrade

Critical thinking skill is an ability beyond thinking rationally and clearly. It is a process of thinking independently and working at your own feet in formulating own opinions or new theory by utilizing critical analysis on the interrelationship of two or more ideas and delineating conclusions without external control (Wabisabi Learning, 2020).

Modified Wabisabi Learning’s 12 Solid Strategies for Teaching Critical Thinking Skills, and its Application to Nursing Education, Training and Practice:

1. Practice on Eloquence in Question and Answer (Solution Fluency)

Mastery requires ample amount of practice to become highly skilled in critical thinking. Accustom to deliberate open discussions encouraging brainstorming on issues affecting the practice and daily living by using explicit open-ended questions and comprehensive instructions for problem-solving may provide opportunities to apply knowledge into practice as well as encouraging the transfer of ideas between domains (Haber, 2020). Brainstorming is an excellent learning tool to exercise critical thinking (Walden University, 2020) particularly if applied in a situational crisis or a hospital scenario.

2. Create a Foundation

From the theory of back to basic, mastery of low-level skills is a requirement in preparatory to the application of critical thinking skills (Kaminske, 2019).

Learning experiences from theoretical and experiential knowledge are good foundations to start critical thinking. Moreover, practicing thinking skills obtained from theoretical and experiential undertakings improve intellectual ability (Berman, et. al., 2016). Practical understanding and specialization on a particular focus may excel you more in thinking critically. The competence and skills acquired from clinical experience are the most essential learning in developing clinical judgment.

3. Consult the Classics

Nursing theorists and their work are the best examples of consulting the classics. In critical thinking, nurses identify claims based on facts, conclusions, judgment/opinions and evidence-based practice. Exploring nursing theorists and their works are like exploring great minds, acquiring lessons on character motivation, refuting theories or formulating a new theory from existing theory. Case studies and in-depth objective critiques of nursing theories may not only promote critical thinking but act as a leverage to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

4. Create an Environment for Open Communication

During clinical rounds, nurses and/or students with a clinical instructor are engaged into thinking process by providing the opportunity to communicate assessment data, collaborate ideas, formulate nursing care plan, and discuss the various context of the situation from different perspectives (Di Vito-Thomas, 2005).

5. Use Information Fluency

Information fluency is mastering the proper use of information and to the ability to intuitively analyze and interpret it in unearthing knowledge and appropriate facts useful in solving a problem (Wabisabi Learning, 2020).

Knowledge of medical conditions, procedures and its connections to patient’s care are important in building critical thinking. Learning from available resources like medical journals, surfing the internet, and meaningful dialogue with colleagues can increase your medical know-how (Jillings, 2020).

6. Utilize Peer Groups

Peer groups, particularly well experienced and highly skilled colleagues are an excellent source of information, questions, and problem-solving techniques as it expands thinking and viewpoints. It also develops interpersonal skills like teamwork and resolving conflicts (Berman, et. Al., 2016).

7. Try One Sentence of Reflections at a time

Reflections will teach the learner to apply their knowledge, logic and reasoning by explaining themselves in a low-pressure setting. It provides an opportunity to explore situations with a different approach and better solutions for future use (Jillings, 2020).

The mastery of metacognition helps the learner to use reflection in defining clinical experiences and explore ways on how to improve it. Recollecting facts and events in patient’s care may integrate the learner into different concepts by connecting different ideas from one another (Di Vito-Thomas, 2005).

8. Problem-solving with Reasoning

Understanding rationale, the sets of reasons or logical basis for a course of action assist the learners to gain a broad knowledge of the topic and promotes a higher level of understanding. Problem-solving guided by rationale is a technique to the use of deductive and inductive reasoning in the thinking process (Di Vito-Thomas, 2005).

9. Roleplaying and Return Demonstration

Role-playing is a self-directed activity that encourages analytic and creative thinking. It helps the learner to internalize empathy while compromising in portraying a role or another persona creating a wider chance for memory retention.

Practice and repetition of observed procedures during return demonstration creates an avenue for re-thinking ways on how to do a task properly with ease in your own phase as you implement it by yourself.

10. Thinking and Speaking With Sketch (Concept Mapping)

Incorporating a concept with multiple perspectives and connecting complex ideas in a structured way to search for potential solutions. These processes create an abstract concept that encourages logical arguments used in critical thinking (Kaminske, 2019).

Interactive activities such as case study with a panel discussion, observing clinical dynamics during in-depth arguments, making a multidisciplinary joint care plan for patient promotes an environment for critical thinking thus facilitating the development of clinical judgment (Di Vito-Thomas, 2005).

11. Do Some Prioritizing and Decision-making

Make critical thinking as a culture and not just an activity by encouraging decision-making. Prioritizing through analyzing information, applying knowledge, and evaluating a prospected solution are the cornerstones of decision-making. This will allows the learner to apply learned theories to a different scenario by weighing the advantages and disadvantages of different solutions and option in deciding best practices.

12. Correct Misconceptions and Personal Bias

Personal beliefs greatly influence one’s ability to think critically as people always seek out ideas that conform to their own beliefs (Kaminske (2019). Several factors that act as the pitfalls in critical thinking are misconceptions, personal bias, and assumptions—which can bring a learner into a wrong direction. A discussion with colleagues who have mastery in evidence-based practice and conducting more in-depth investigations can give ideas and extends point of view (Jillings, 2020).

Conclusion and Suggestions:

Analytical skills through keen observation, understanding important data, and identifying a pattern of recognition; problem-solving capacity by connecting relationship of phenomena, data interpretation guided by significance and rationale; and use of reflection and evaluation abilities in formulating conclusion are the important factors in clinical judgment and decision-making.

Critical thinking is a learned skill resulted from a rolled-up innate curiosity in the application of strong theoretical and experiential foundations in solving clinical problems that direct to the best care decision, which produce positive patient outcomes and improve patient care services.

In this era of technological advancement where machine replaces almost of everything, critical thinking still plays an important role in the nursing practice. Nurses who can manipulate complex clinical situations with efficient skills on critical/analytical thinking, problem-solving and decision-making are often in the front line to compete for the position with greater autonomy and higher chances for opportunities.

- Nightingale, F. (1860). Notes on Nursing: What it Is, and what it is Not. London: Harrisons & Sons.

- Haber, J. (2020). It’s Time to Get Serious About Teaching Critical Thinking. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved on 24 October 2020 from https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/03/02/teaching-students-think-critically-opinion

- Walden University. (2020). 7 Ways to Teach Critical Thinking in Elementary Education. Retrieved on 24 October 2020 from https://www.waldenu.edu/online-bachelors-programs/bs-in-elementary-education/resource/seven-ways-to-teach-critical-thinking-in-elementary-education

- Kaminske, A.N. (2019). Can We Teach Critical Thinking?. The Learning Scientists. Retrieved on 24 October 2020 from https://www.learningscientists.org/blog/2019/2/28/can-we-teach-critical-thinking#:~:text=beliefs%20(3).-,Can%20we%20teach%20critical%20thinking%3F,happens%20to%20enjoy%20science%20fiction

- Berman, A., Snyder, S.J. & Frandsen, G. (2016). Kozier & Erb’s Fundamentals of Nursing: Concepts, Process, and Practice, 10 th New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Lakhanigam, S. (2017). Critical Thinking: A Vital Trait for Nurses. Minority Nurse. Retrieved on 24 October 2020 from https://minoritynurse.com/critical-thinking-vital-trait-nurses/

- Regis College (2020). How to Leverage Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice. Retrieved on 24 October 2020 from https://online.regiscollege.edu/blog/how-to-leverage-critical-thinking-in-nursing-practice/

- (2020). Tabula Rasa. Retrieved on 24 October 2020 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tabula_rasa

- Willis, J. (2012). A Neurologist Makes the Case for Teaching Teachers About the Brain. George Lucas Educational Foundation. Retrieved on 24 October 2020 from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/neuroscience-higher-ed-judy-willis

- Knowles, M. (1984). The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species, 3 rd Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing.

- Seel, N.M. (2012). Assimilation Theory of Learning. In: Seel N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_358

- Luna, A. (2020). 7 Reasons Critical Thinking In Nursing Is Important. AMN Healthcare Company. Retrieved on 24 October 2002 from https://www.onwardhealthcare.com/nursing-resources/seven-reasons-critical-thinking-in-nursing-is-important/

- Wabisabi Learning. (2020). 12 Solid Strategies for Teaching Critical Thinking Skills. Retrieved on 24 October 2020 from https://wabisabilearning.com/blogs/critical-thinking/teaching-critical-thinking-skills

- Di Vito-Thomas, P. (2005). Nursing Student Stories on Learning How to Think Like a Nurse. Nurse Educator, 30(3), pp. 133-136.

- Jillings, B. (2020). Critical Thinking in Nursing: Why It’s Important and How to Improve. AMN Healthcare Company. Retrieved on 24 October 2020 from https://www.americanmobile.com/mobile/NZArticle/?articleId=3346

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Autism: A Comprehensive Guide to Raising and Supporting a Child with Autism

The Most Common Types of Eating Disorder

120+ Fresh Nursing Essay Topics (With FAQs and Essay Writing Tips)

Nursing Personal Statement: Your Voice in Writing

The Nursing Essay: Learning How to Write

COVID-19: The Nursing Case Management Approach

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing? (Explained W/ Examples)

- Ummu, MN, BSN, CCN, RN

- Fundamentals

- August 23, 2023

Critical thinking is a foundational skill applicable across various domains, including education, problem-solving, decision-making, and professional fields such as science, business, healthcare, and more.

It plays a crucial role in promoting logical and rational thinking, fostering informed decision-making, and enabling individuals to navigate complex and rapidly changing environments.

In this article, we will look at what is critical thinking in nursing practice, its importance, and how it enables nurses to excel in their roles while also positively impacting patient outcomes.

Table of Contents

What is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is a cognitive process that involves analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to make reasoned and informed decisions.

It’s a mental activity that goes beyond simple memorization or acceptance of information at face value.

Critical thinking involves careful, reflective, and logical thinking to understand complex problems, consider various perspectives, and arrive at well-reasoned conclusions or solutions.

Key aspects of critical thinking include:

- Analysis: Critical thinking begins with the thorough examination of information, ideas, or situations. It involves breaking down complex concepts into smaller parts to better understand their components and relationships.

- Evaluation: Critical thinkers assess the quality and reliability of information or arguments. They weigh evidence, identify strengths and weaknesses, and determine the credibility of sources.

- Synthesis: Critical thinking involves combining different pieces of information or ideas to create a new understanding or perspective. This involves connecting the dots between various sources and integrating them into a coherent whole.

- Inference: Critical thinkers draw logical and well-supported conclusions based on the information and evidence available. They use reasoning to make educated guesses about situations where complete information might be lacking.

- Problem-Solving: Critical thinking is essential in solving complex problems. It allows individuals to identify and define problems, generate potential solutions, evaluate the pros and cons of each solution, and choose the most appropriate course of action.

- Creativity: Critical thinking involves thinking outside the box and considering alternative viewpoints or approaches. It encourages the exploration of new ideas and solutions beyond conventional thinking.

- Reflection: Critical thinkers engage in self-assessment and reflection on their thought processes. They consider their own biases, assumptions, and potential errors in reasoning, aiming to improve their thinking skills over time.

- Open-Mindedness: Critical thinkers approach ideas and information with an open mind, willing to consider different viewpoints and perspectives even if they challenge their own beliefs.

- Effective Communication: Critical thinkers can articulate their thoughts and reasoning clearly and persuasively to others. They can express complex ideas in a coherent and understandable manner.

- Continuous Learning: Critical thinking encourages a commitment to ongoing learning and intellectual growth. It involves seeking out new knowledge, refining thinking skills, and staying receptive to new information.

Definition of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is an intellectual process of analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to make reasoned and informed decisions.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing is a vital cognitive skill that involves analyzing, evaluating, and making reasoned decisions about patient care.

It’s an essential aspect of a nurse’s professional practice as it enables them to provide safe and effective care to patients.

Critical thinking involves a careful and deliberate thought process to gather and assess information, consider alternative solutions, and make informed decisions based on evidence and sound judgment.

This skill helps nurses to:

- Assess Information: Critical thinking allows nurses to thoroughly assess patient information, including medical history, symptoms, and test results. By analyzing this data, nurses can identify patterns, discrepancies, and potential issues that may require further investigation.

- Diagnose: Nurses use critical thinking to analyze patient data and collaboratively work with other healthcare professionals to formulate accurate nursing diagnoses. This is crucial for developing appropriate care plans that address the unique needs of each patient.

- Plan and Implement Care: Once a nursing diagnosis is established, critical thinking helps nurses develop effective care plans. They consider various interventions and treatment options, considering the patient’s preferences, medical history, and evidence-based practices.

- Evaluate Outcomes: After implementing interventions, critical thinking enables nurses to evaluate the outcomes of their actions. If the desired outcomes are not achieved, nurses can adapt their approach and make necessary changes to the care plan.

- Prioritize Care: In busy healthcare environments, nurses often face situations where they must prioritize patient care. Critical thinking helps them determine which patients require immediate attention and which interventions are most essential.

- Communicate Effectively: Critical thinking skills allow nurses to communicate clearly and confidently with patients, their families, and other members of the healthcare team. They can explain complex medical information and treatment plans in a way that is easily understood by all parties involved.

- Identify Problems: Nurses use critical thinking to identify potential complications or problems in a patient’s condition. This early recognition can lead to timely interventions and prevent further deterioration.

- Collaborate: Healthcare is a collaborative effort involving various professionals. Critical thinking enables nurses to actively participate in interdisciplinary discussions, share their insights, and contribute to holistic patient care.

- Ethical Decision-Making: Critical thinking helps nurses navigate ethical dilemmas that can arise in patient care. They can analyze different perspectives, consider ethical principles, and make morally sound decisions.

- Continual Learning: Critical thinking encourages nurses to seek out new knowledge, stay up-to-date with the latest research and medical advancements, and incorporate evidence-based practices into their care.

In summary, critical thinking is an integral skill for nurses, allowing them to provide high-quality, patient-centered care by analyzing information, making informed decisions, and adapting their approaches as needed.

It’s a dynamic process that enhances clinical reasoning , problem-solving, and overall patient outcomes.

What are the Levels of Critical Thinking in Nursing?

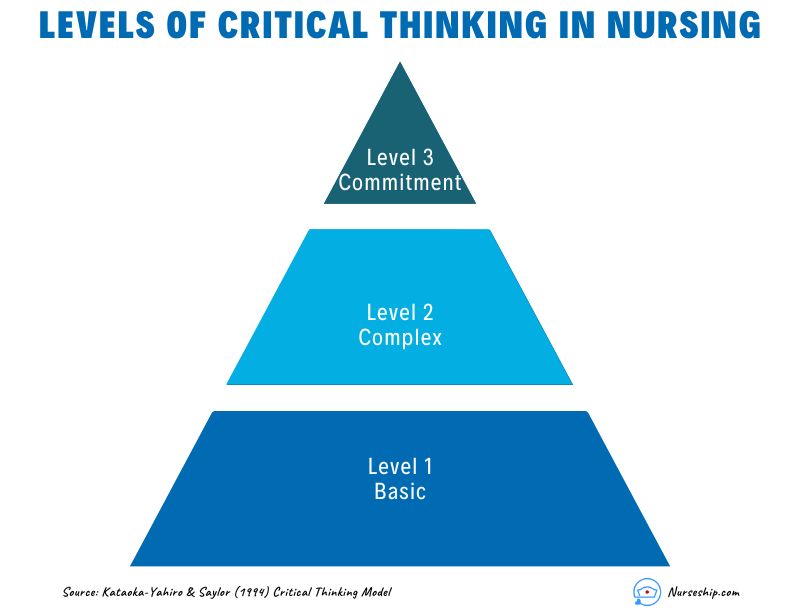

The development of critical thinking in nursing practice involves progressing through three levels: basic, complex, and commitment.

The Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor model outlines this progression.

1. Basic Critical Thinking:

At this level, learners trust experts for solutions. Thinking is based on rules and principles. For instance, nursing students may strictly follow a procedure manual without personalization, as they lack experience. Answers are seen as right or wrong, and the opinions of experts are accepted.

2. Complex Critical Thinking:

Learners start to analyze choices independently and think creatively. They recognize conflicting solutions and weigh benefits and risks. Thinking becomes innovative, with a willingness to consider various approaches in complex situations.

3. Commitment:

At this level, individuals anticipate decision points without external help and take responsibility for their choices. They choose actions or beliefs based on available alternatives, considering consequences and accountability.

As nurses gain knowledge and experience, their critical thinking evolves from relying on experts to independent analysis and decision-making, ultimately leading to committed and accountable choices in patient care.

Why Critical Thinking is Important in Nursing?

Critical thinking is important in nursing for several crucial reasons:

Patient Safety:

Nursing decisions directly impact patient well-being. Critical thinking helps nurses identify potential risks, make informed choices, and prevent errors.

Clinical Judgment:

Nursing decisions often involve evaluating information from various sources, such as patient history, lab results, and medical literature.

Critical thinking assists nurses in critically appraising this information, distinguishing credible sources, and making rational judgments that align with evidence-based practices.

Enhances Decision-Making:

In nursing, critical thinking allows nurses to gather relevant patient information, assess it objectively, and weigh different options based on evidence and analysis.

This process empowers them to make informed decisions about patient care, treatment plans, and interventions, ultimately leading to better outcomes.

Promotes Problem-Solving:

Nurses encounter complex patient issues that require effective problem-solving.

Critical thinking equips them to break down problems into manageable parts, analyze root causes, and explore creative solutions that consider the unique needs of each patient.

Drives Creativity:

Nursing care is not always straightforward. Critical thinking encourages nurses to think creatively and explore innovative approaches to challenges, especially when standard protocols might not suffice for unique patient situations.

Fosters Effective Communication:

Communication is central to nursing. Critical thinking enables nurses to clearly express their thoughts, provide logical explanations for their decisions, and engage in meaningful dialogues with patients, families, and other healthcare professionals.

Aids Learning:

Nursing is a field of continuous learning. Critical thinking encourages nurses to engage in ongoing self-directed education, seeking out new knowledge, embracing new techniques, and staying current with the latest research and developments.

Improves Relationships:

Open-mindedness and empathy are essential in nursing relationships.

Critical thinking encourages nurses to consider diverse viewpoints, understand patients’ perspectives, and communicate compassionately, leading to stronger therapeutic relationships.

Empowers Independence:

Nursing often requires autonomous decision-making. Critical thinking empowers nurses to analyze situations independently, make judgments without undue influence, and take responsibility for their actions.

Facilitates Adaptability:

Healthcare environments are ever-changing. Critical thinking equips nurses with the ability to quickly assess new information, adjust care plans, and navigate unexpected situations while maintaining patient safety and well-being.

Strengthens Critical Analysis:

In the era of vast information, nurses must discern reliable data from misinformation.

Critical thinking helps them scrutinize sources, question assumptions, and make well-founded choices based on credible information.

How to Apply Critical Thinking in Nursing? (With Examples)

Here are some examples of how nurses can apply critical thinking.

Assess Patient Data:

Critical Thinking Action: Carefully review patient history, symptoms, and test results.

Example: A nurse notices a change in a diabetic patient’s blood sugar levels. Instead of just administering insulin, the nurse considers recent dietary changes, activity levels, and possible medication interactions before adjusting the treatment plan.

Diagnose Patient Needs:

Critical Thinking Action: Analyze patient data to identify potential nursing diagnoses.

Example: After reviewing a patient’s lab results, vital signs, and observations, a nurse identifies “ Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity ” due to the patient’s limited mobility.

Plan and Implement Care:

Critical Thinking Action: Develop a care plan based on patient needs and evidence-based practices.

Example: For a patient at risk of falls, the nurse plans interventions such as hourly rounding, non-slip footwear, and bed alarms to ensure patient safety.

Evaluate Interventions:

Critical Thinking Action: Assess the effectiveness of interventions and modify the care plan as needed.

Example: After administering pain medication, the nurse evaluates its impact on the patient’s comfort level and considers adjusting the dosage or trying an alternative pain management approach.

Prioritize Care:

Critical Thinking Action: Determine the order of interventions based on patient acuity and needs.

Example: In a busy emergency department, the nurse triages patients by considering the severity of their conditions, ensuring that critical cases receive immediate attention.

Collaborate with the Healthcare Team:

Critical Thinking Action: Participate in interdisciplinary discussions and share insights.

Example: During rounds, a nurse provides input on a patient’s response to treatment, which prompts the team to adjust the care plan for better outcomes.

Ethical Decision-Making:

Critical Thinking Action: Analyze ethical dilemmas and make morally sound choices.

Example: When a terminally ill patient expresses a desire to stop treatment, the nurse engages in ethical discussions, respecting the patient’s autonomy and ensuring proper end-of-life care.

Patient Education:

Critical Thinking Action: Tailor patient education to individual needs and comprehension levels.

Example: A nurse uses visual aids and simplified language to explain medication administration to a patient with limited literacy skills.

Adapt to Changes:

Critical Thinking Action: Quickly adjust care plans when patient conditions change.

Example: During post-operative recovery, a nurse notices signs of infection and promptly informs the healthcare team to initiate appropriate treatment adjustments.

Critical Analysis of Information:

Critical Thinking Action: Evaluate information sources for reliability and relevance.

Example: When presented with conflicting research studies, a nurse critically examines the methodologies and sample sizes to determine which study is more credible.

Making Sense of Critical Thinking Skills

What is the purpose of critical thinking in nursing.

The purpose of critical thinking in nursing is to enable nurses to effectively analyze, interpret, and evaluate patient information, make informed clinical judgments, develop appropriate care plans, prioritize interventions, and adapt their approaches as needed, thereby ensuring safe, evidence-based, and patient-centered care.

Why critical thinking is important in nursing?

Critical thinking is important in nursing because it promotes safe decision-making, accurate clinical judgment, problem-solving, evidence-based practice, holistic patient care, ethical reasoning, collaboration, and adapting to dynamic healthcare environments.

Critical thinking skill also enhances patient safety, improves outcomes, and supports nurses’ professional growth.

How is critical thinking used in the nursing process?

Critical thinking is integral to the nursing process as it guides nurses through the systematic approach of assessing, diagnosing, planning, implementing, and evaluating patient care. It involves:

- Assessment: Critical thinking enables nurses to gather and interpret patient data accurately, recognizing relevant patterns and cues.

- Diagnosis: Nurses use critical thinking to analyze patient data, identify nursing diagnoses, and differentiate actual issues from potential complications.

- Planning: Critical thinking helps nurses develop tailored care plans, selecting appropriate interventions based on patient needs and evidence.

- Implementation: Nurses make informed decisions during interventions, considering patient responses and adjusting plans as needed.

- Evaluation: Critical thinking supports the assessment of patient outcomes, determining the effectiveness of intervention, and adapting care accordingly.

Throughout the nursing process , critical thinking ensures comprehensive, patient-centered care and fosters continuous improvement in clinical judgment and decision-making.

What is an example of the critical thinking attitude of independent thinking in nursing practice?

An example of the critical thinking attitude of independent thinking in nursing practice could be:

A nurse is caring for a patient with a complex medical history who is experiencing a new set of symptoms. The nurse carefully reviews the patient’s history, recent test results, and medication list.

While discussing the case with the healthcare team, the nurse realizes that the current treatment plan might not be addressing all aspects of the patient’s condition.

Instead of simply following the established protocol, the nurse independently considers alternative approaches based on their assessment.

The nurse proposes a modification to the treatment plan, citing the rationale and evidence supporting the change.

This demonstrates independent thinking by critically evaluating the situation, challenging assumptions, and advocating for a more personalized and effective patient care approach.

How to use Costa’s level of questioning for critical thinking in nursing?

Costa’s levels of questioning can be applied in nursing to facilitate critical thinking and stimulate a deeper understanding of patient situations. The levels of questioning are as follows:

- 15 Attitudes of Critical Thinking in Nursing (Explained W/ Examples)

- Nursing Concept Map (FREE Template)

- Clinical Reasoning In Nursing (Explained W/ Example)

8 Stages Of The Clinical Reasoning Cycle

- How To Improve Critical Thinking Skills In Nursing? 24 Strategies With Examples

- What is the “5 Whys” Technique?

- What Are Socratic Questions?

Critical thinking in nursing is the foundation that underpins safe, effective, and patient-centered care.

Critical thinking skills empower nurses to navigate the complexities of their profession while consistently providing high-quality care to diverse patient populations.

Reading Recommendation

Potter, P.A., Perry, A.G., Stockert, P. and Hall, A. (2013) Fundamentals of Nursing

Related Posts

JCAHO’s “DO NOT USE” abbreviations list (updated 2024)

Dorsal Recumbent Position |Definition |Uses |Image

- Visit Nurse.com on Facebook

- Visit Nurse.com on YouTube

- Visit Nurse.com on Instagram

- Visit Nurse.com on LinkedIn

Nurse.com by Relias . © Relias LLC 2025. All Rights Reserved.

Why Critical Thinking Is Important in Nursing

Most nursing professionals have natural nurturing abilities, a desire to give others support, and an appreciation for science and anatomy. Successful nurses also possess a skill that is often overlooked: they can think critically.

A critical thinker will identify the problem, determine the best solution, and choose the most effective method. Critical thinkers evaluate the execution of a plan to see if it was effective and if it could have been done better.

The ability to think critically has multiple applications in your life, as you can see. But Why is critical thinking important in nursing? Learn why and how you can improve this skill by reading on.

Why Are Critical Thinking Skills in Nursing Important?

Critical thinking is an essential skill for nursing students to have. It’s not something that it can teach in a classroom, and it must be developed over time through experience and practice.

Critical thinking is the process of applying logic and reason to make decisions or solve problems. The ability to think critically will help you make better decisions on your own and collaborate with others when solving problems – both are essential skills for nurses.

Nursing has always been a profession that relies on critical thinking. Nurses are constantly faced with new situations and problems, which they need to think critically about to solve.

Critical thinking is essential for nurses because it helps them make decisions based on the available information and their past experiences and knowledge of the field. It also allows nurses to plan before making any changes to be most effective as possible.

It is an essential skill for nurses to have to provide the best care possible. Critical thinkers can comprehend a problem and think about how they can solve it, rather than reactively or automatically.

Critical thinking is a crucial skill for doctors, nurses, and other health care providers.

How can you develop your critical thinking skills?

As you know, learning doesn’t end when you graduate from nursing school. You must continue to grow as a professional and develop your critical thinking skills.

Critical thinkers are better problem solvers than others in the same situation because they examine all the facts before coming up with solutions. They can also take many different perspectives into account when solving problems.

It’s easy for people to come to conclusions too quickly, but those who think critically will avoid this trap by first looking at every possible angle.

When faced with difficult decisions, these nurses won’t just rely on their gut feelings or what seems right according to society’s norms; instead, they’ll analyze all available information carefully until they develop the best solution.

Critical thinking is also crucial because it helps nurses avoid making mistakes in their work by providing them with a way to examine each situation and identify any potential risks or problems that may arise from subsequent actions before they take place.

It’s not enough for you to have empathy if your compassion isn’t backed up by critical thought and understanding of how certain decisions might affect others in various circumstances, so keep learning ways to become more thoughtful about the world around you.

The skills involved in being a good nurse are many and varied, but one thing all nurses need, regardless of what specialty they choose, is critical solid thinking abilities.

Reasons Critical Thinking In Nursing Is Important

Nurses’ experiences often include making life-altering decisions, establishing authority in stressful situations, and helping patients and their loved ones cope with some of the most stressful and emotional times of their lives. Critical thinking is an essential aspect of nursing.

Following are the reasons:

- Nurses’ critical thinking has a significant impact on patient care

- Recognizing changes in patient status is essential

- It’s essential to an honest and open exchange of ideas

- It enables you to ensure patient safety

- Nurses can find quick fixes with it

- Improvements can be made through critical thinking

- It Contributes to Rational Decision Making

Further critical thinking is essential to nursing because nurses can establish authority in a stressful situation, such as issuing orders or administering care when needed.

This can be difficult because it may require balancing medical expertise with empathy and compassion towards patients’ feelings, leading them to question your judgment at some point in time.

Another reason this skill set is crucial involves making decisions that will have life-changing effects on a patient’s health and well-being.

These are often irreversible choices that only you know how much weight they carry within the context of each situation, so you need to make sure all factors are carefully considered before deciding what action must be taken next without hesitation.

Skills that Critical Thinkers Need

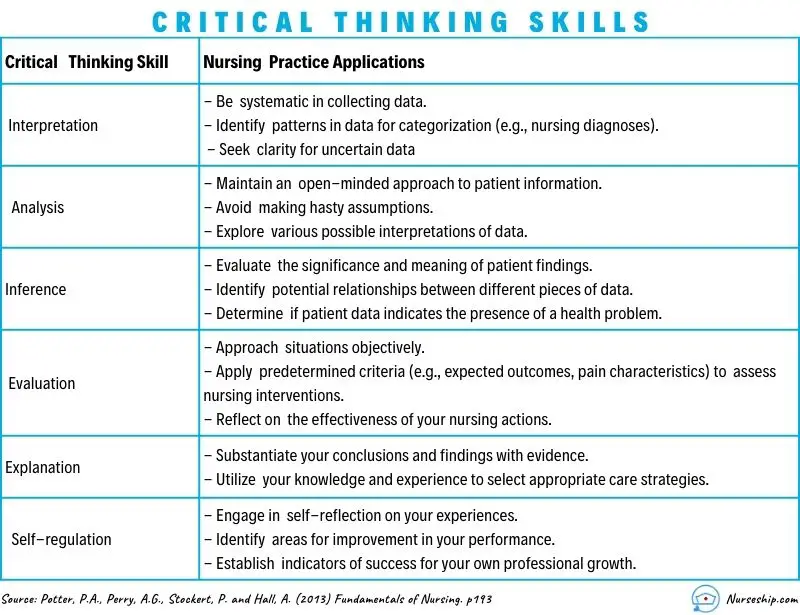

When it comes to critical thinking, some skills are more important than others. Using a framework known as the Nursing Process, some of these skills are applied to patient care. The most important skills are:

Interpretation: Understanding and explaining a specific event or piece of information.

Analysis: Studying data based on subjective and objective information to determine the best course of action.

Evaluation: Here, you assess the information you received. Is the information accurate, reliable, and credible? The ability to determine if outcomes have been fully achieved requires this skill as well.

The nurse can then use clinical reasoning to determine what the problem is based on those three skills.

The decisions need to be based on sound reasoning:

Provide a clear, concise explanation of your conclusions. Nurses should provide a rationale for their answers.

Self-regulation – You need to be aware of your thought processes. As a result, you must reflect on the process that led to your conclusion. In this process, you should self-correct as necessary. Keep an eye out for bias and incorrect assumptions.

Critical Thinking Pitfalls

It can fall by the wayside when it’s not seen as necessary or when there are more pressing issues.

- Critical thinking is important in nursing because it can fall by the wayside when it’s not seen as an essential or more pressing issue.

- It can be difficult to think critically about complex, ambiguous situations with a shortage of information and time in healthcare settings.

- If we don’t use critical thinking skills, problems might go undetected or unresolved, leading to further complications down the road.

Sometimes nurses can’t differentiate between a less acute clinical problem and one that needs immediate attention. When a large amount of complex data must be processed in a time-critical manner, errors can also occur.

Conclusion:

Nurses cannot overstate the importance of critical thinking. The clinical presentations of patients are diverse. To provide safe, high-quality care, nurses must make rational clinical decisions and solve problems. Nurses need critical thinking skills to handle increasingly complex cases.

- Why Is Research Important in Nursing?

- Why Is the Nursing Process Important?

- Why Compassion is Important in Nursing

About The Author

Brittney wilson, bsn, rn, related posts.

Funny Nurse Memes to Brighten Your Day

A Guide To The Most Useful Free Nursing Apps

Most Popular Shoes for Nurses: Alegria Clog

Best Nursing Jobs for Work Life Balance: Increase Your Earnings While Working from Home

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Start typing and press enter to search

The university of tulsa Online Blog

Trending topics in the tu online community

Why Critical Thinking Skills in Nursing Are Essential

Working in health care requires quick thinking and confident decision-making to care for patients. While nurses use a broad range of technical skills to provide quality care, an essential skill that’s easy to overlook is critical thinking. Nursing professionals should explore the benefits of critical thinking skills in nursing, how to apply them, and the ways that advanced education can sharpen their ability to make precise decisions.

Critical Thinking Skills: A Definition

Critical thinking is the process of evaluating facts, interpreting information, and analyzing situations to make informed decisions in various situations. Finding the correct answer to a complex problem isn’t easy. When situations don’t have clear answers and many factors to consider, critical thinking can help individuals move forward and make decisions.

Critical thinking competencies can be applied to a wide range of workplaces and personal situations. In nursing, critical thinking skills can help deliver effective care, handle a patient crisis, and assess the efficacy of treatment plans.

The Importance of Critical Thinking Skills in Nursing

The fast-paced nursing environment requires prompt, data-driven decisions. Nurses use critical thinking daily, reviewing information and making decisions to promote quality care for patients. The following benefits of critical thinking highlight the importance of this skill in nursing careers:

Improves decision-making speed. A critical thinking mindset can help nurses make timely, effective decisions in difficult situations. A systematic method to evaluate decisions and move forward is a powerful tool for nurses.

Refines communication. Improving professional communication allows for factual, efficient, and empathetic conversations with patients and other health care professionals.

Promotes open-mindedness. It’s easy to overlook certain opinions or viewpoints in a high-pressure situation. Thankfully, critical thinking promotes open-mindedness in exploring solutions.

Combats bias. A critical look at different behaviors, contexts, and viewpoints can be helpful for identifying and addressing bias. Nurses must actively seek out ways to confront and remove bias in the workplace.

Critical Thinking in the Nursing Process

There are many ways to apply critical thinking skills to nursing situations. The nursing process is a five-step process to assist nurses in applying critical thinking skills to their daily duties. Experienced nurses and professionals considering a career change to nursing should review the steps as part of their critical thinking process.

Step 1: Assessment

Assessing a patient means far more than taking their vital signs. It also includes collecting sociocultural and psychological data. Lifestyle factors and experiences can affect the treatment process and approach, so skilled nurses review these areas before moving toward the next step, diagnosis.

For example, if a patient reports dizziness or shortness of breath, a nurse should not only check the patient’s temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate but also ask about their family history and recent events.

Step 2: Diagnosis

During the second step, a nurse’s assessment and critical thinking skills produce a clinical judgment. Nurses need to carefully consider all the factors included in the first step. When necessary, consult with other health care professionals before reaching a diagnosis or communicating that diagnosis with the patient.

Discussing a patient’s assessment with other health care professionals requires critical thinking, as the information provided about vital signs, recent events, and family history are key components of this step.

Step 3: Planning

A nurse may be responsible for setting goals and planning a treatment plan for patients. The third step can include setting measurable, achievable goals. Nurses also coordinate care with other health care professionals.

Goals can be simple or complex, depending on the assessment and diagnosis. For example, one patient’s goals may include eating three meals a day, while another’s may include having multiple medications, specialist visits, and physical therapy activities as part of their treatment plan.

Step 4: Implementation

Critical thinking is needed to implement the nursing process, finding ways to carry out the plan with empathy. It’s also important for nurses to document care throughout the fourth step of the process.

For example, nurses should review patient history and consider symptoms before administering medication. Nursing professionals should also think critically about which patients to see first and how to prioritize patients who may need critical attention.

Step 5: Evaluation

Nurses need to continue to evaluate and review the patient’s condition using critical thinking. Evaluation allows nursing professionals to review patient conditions, recommend care plan modification, and consider overall patient status.

For example, identifying whether patients may be ready for a care plan modification or another change in care requires critical thinking and a clear, focused evaluation of multiple patient factors.

How to Foster Critical Thinking Through Nursing Education

Critical thinking is integral to success in the health care field. Thankfully, many ways are available for nurses to improve their critical thinking skills. Below are training, mentoring, and education options for fostering critical thinking.

On-the-Job Training

Because critical thinking is so critical to the daily duties of nurses, experience in the field can improve their ability to evaluate situations and make data-driven decisions. Working firsthand with patients and alongside skilled professionals is a powerful way to see and apply critical thinking in real-world scenarios.

Mentoring Opportunities

Nurses should seek mentorship opportunities for personalized, side-by-side instruction and inspiration from fellow professionals. Mentorships can be either formal or informal opportunities to learn from skilled nurses and health care professionals to promote critical thinking.

Further Education

Many continuing education opportunities are available for nurses. Professionals looking to improve their critical thinking skills should consider enrolling in a course that promotes reflection, evaluation, and analytical thinking.

Review Critical Thinking Skills With The University of Tulsa

Expand your critical thinking skills in nursing by enrolling in a program to earn a degree in the field. The University of Tulsa offers an accelerated online RN to Bachelor of Science in Nursing (RN to BSN) program for students to earn their BSN in as little as 12 months. Take 30 credits of online courses to expand your medical knowledge, general education, and critical thinking abilities. Review the features of this online opportunity to see if it’s the right decision for your career.

Recommended Readings:

The Benefits of Nurse Mentoring

Hospice Nurse: Job Description and Salary

Work-From-Home Safety Checklist: Securing Your Virtual Workspace

American Nurses Association, The Nursing Process

American Nurses Association, What Are the Qualities of a Good Nurse?

Forbes , “The Power of Critical Thinking: Enhancing Decision-Making and Problem-Solving”

Indeed, “Critical Thinking in Nursing (Definition and Vital Tips)”

Indeed, “Critical Thinking Skills in Nursing: Definition and Improvement Tips”

Indeed, “15 Essential Nursing Skills to Include on Your Resume”

StatPearls, “Nursing Process”

Recent Articles

Is Oklahoma a Compact Nursing State?

University of Tulsa

Jan 13, 2025

Nurse Work Environments: How an MSN Can Broaden Opportunities

Jan 7, 2025

RN to BSN: Requirements for Prospective Students

Learn more about the benefits of receiving your degree from the university of tulsa.

- Online Program Tuition

- AGACNP Certificate Online

- Online MSN Program

- Accelerated Online BSN

- RN to BSN Program

- RN to MSN Program

- MS in Cyber Security

- Meet the Team

- Nursing Student Practicum Requirements

- Disclosures for Professional Nursing Licensure

- On Campus Programs

- ACN FOUNDATION

- SIGNATURE EVENTS

- SCHOLARSHIPS

- POLICY & ADVOCACY

- ACN MERCHANDISE

- MYACN LOGIN

- THE BUZZ LOGIN

- STUDENT LOGIN

- Celebrating 75 years

- ACN governance and structure

- Work at ACN

- Contact ACN

- NurseClick – ACN’s blog

- Media releases

- Publications

- ACN podcast

- Men in Nursing

- NurseStrong

- Recognition of Service

- Free eNewsletter

- Areas of study

- Graduate Certificates

- Nursing (Re-entry)

- Continuing Professional Development

- Immunisation courses

- Single units of study

- Transition to Practice Program

- Audiometry Nursing in Practice

- Refresher programs

- Principles of Emergency Care

- Medicines Management Course

- Professional Practice Course

- Endorsements

- Student support

- Student policies

- Clinical placements

- Career mentoring

- Indemnity insurance

- Legal advice

- ACN representation

- Affiliate membership

- Undergraduate membership

- Retired membership

- States and Territories

- ACN Fellowship

- Referral discount

- Emerging Nurse Leader program

- Emerging Policy Leader Program

- Emerging Research Leader Program

- Nurse Unit Manager Leadership Program

- Nurse Director Leadership Program

- Nurse Executive Leadership Program

- The Leader’s Series

- Health Minister’s Award for Nursing Trailblazers

- Thought leadership

- Other leadership courses

- Policy Summit

- Nursing & Health Expo

- National Nurses Breakfast

- National Nursing Forum

- Virtual Open Day

- Event and webinar calendar

- Grants and awards

- External nursing scholarships

- Assessor’s login

- ACN Advocacy and Policy

- Position Statements

- Submissions

- White Papers

- Clinical care standards

- Aged Care Solutions Expert Advisory Group

- Nurses and Violence Taskforce

- Parliamentary Friends of Nursing

- Aged Care Transition to Practice Program

- Immunisation

- Join as an Affiliated Organisation

- Our Affiliates

- Our Corporate Partners

- Events sponsorship

- Advertise with us

- Career Hub resources

- Critical Thinking

Q&A: What is critical thinking and when would you use critical thinking in the clinical setting?

(Write 2-3 paragraphs)

In literature ‘critical thinking’ is often used, and perhaps confused, with problem-solving and clinical decision-making skills and clinical reasoning. In practice, problem-solving tends to focus on the identification and resolution of a problem, whilst critical thinking goes beyond this to incorporate asking skilled questions and critiquing solutions.

Critical thinking has been defined in many ways, but is essentially the process of deliberate, systematic and logical thinking, while considering bias or assumptions that may affect your thinking or assessment of a situation. In healthcare, the clinical setting whether acute care sector or aged care critical thinking has generally been defined as reasoned, reflective thinking which can evaluate the given evidence and its significance to the patient’s situation. Critical thinking occasionally involves suspension of one’s immediate judgment to adequately evaluate and appraise a situation, including questioning whether the current practice is evidence-based. Skills such as interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation are required to interpret thinking and the situation. A lack of critical thinking may manifest as a failure to anticipate the consequences of one’s actions.

Critical thinking is that mode of thinking – about any subject, content, or problem — in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them.

The Paul-Elder framework has three components:

- The elements of thought (reasoning)

- The intellectual standards that should be applied to the elements of reasoning

- The intellectual traits associated with a cultivated critical thinker that result from the consistent and disciplined application of the intellectual standards to the elements of thought.

Critical thinking can be defined as, “the art of analysing and evaluating thinking with a view to improving it”. The eight Parts or Elements of Thinking involved in critical thinking: