November 1, 2011

Is Free Will an Illusion?

Don't trust your instincts about free will or consciousness, experimental philosophers say

By Shaun Nichols

IT SEEMS OBVIOUS to me that I have free will . When I have just made a decision, say, to go to a concert, I feel that I could have chosen to do something else. Yet many philosophers say this instinct is wrong. According to their view, free will is a figment of our imagination. No one has it or ever will. Rather our choices are either determined—necessary outcomes of the events that have happened in the past—or they are random.

Our intuitions about free will, however, challenge this nihilistic view. We could, of course, simply dismiss our intuitions as wrong. But psychology suggests that doing so would be premature: our hunches often track the truth pretty well [see “ The Powers and Perils of Intuition ,” by David G. Myers; Scientific American Mind , June/July 2007]. For example, if you do not know the answer to a question on a test, your first guess is more likely to be right. In both philosophy and science, we may feel there is something fishy about an argument or an experiment before we can identify exactly what the problem is.

The debate over free will is one example in which our intuitions conflict with scientific and philosophical arguments. Something similar holds for intuitions about consciousness, morality, and a host of other existential concerns. Typically philosophers deal with these issues through careful thought and discourse with other theorists. In the past decade, however, a small group of philosophers have adopted more data-driven methods to illuminate some of these confounding questions. These so-called experimental philosophers administer surveys, measure reaction times and image brains to understand the sources of our instincts. If we can figure out why we feel we have free will, for example, or why we think that consciousness consists of something more than patterns of neural activity in our brain, we might know whether to give credence to those feelings. That is, if we can show that our intuitions about free will emerge from an untrustworthy process, we may decide not to trust those beliefs.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Unknown Influences To discover the psychological basis for philosophical problems, experimental philosophers often survey people about their views on charged issues. For instance, scholars have argued about whether individuals actually believe that their choices are independent of the past and the laws of nature. Experimental philosophers have tried to resolve the debate by asking study participants whether they agree with descriptions such as the following:

Imagine a universe in which everything that happens is completely caused by whatever happened before it. So what happened in the beginning of the universe caused what happened next and so on, right up to the present. If John decided to have french fries at lunch one day, this decision, like all others, was caused by what happened before it.

When surveyed, Americans say they disagree with such descriptions of the universe . From inquiries in other countries, researchers have found that Chinese, Colombians and Indians share this opinion: individual choice is not determined. Why do humans hold this view? One promising explanation is that we presume that we can generally sense all the influences on our decision making—and because we cannot detect deterministic influences, we discount them.

Of course, people do not believe they have conscious access to everything in their mind. We do not presume to intuit the causes of headaches, memory formation or visual processing. But research indicates that people do think they can access the factors affecting their choices.

Yet psychologists widely agree that unconscious processes exert a powerful influence over our choices. In one study, for example, participants solved word puzzles in which the words were either associated with rudeness or politeness. Those exposed to rudeness words were much more likely to interrupt the experimenter in a subsequent part of the task. When debriefed, none of the subjects showed any awareness that the word puzzles had affected their behavior. That scenario is just one of many in which our decisions are directed by forces lurking beneath our awareness.

Thus, ironically, because our subconscious is so powerful in other ways, we cannot truly trust it when considering our notion of free will. We still do not know conclusively that our choices are determined. Our intuition, however, provides no good reason to think that they are not. If our instinct cannot support the idea of free will, then we lose our main rationale for resisting the claim that free will is an illusion.

Is Consciousness Just a Brain Process? Though a young movement, experimental philosophy is broad in scope. Its proponents apply their methods to varied philosophical problems, including questions about the nature of the self. For example, what (if anything) makes you the same person from childhood to adulthood? They investigate issues in ethics, too: Do people think that morality is objective, as is mathematics, and if so, why? Akin to the question of free will, they are also tackling the dissonance between our intuitions and scientific theories of consciousness.

Scientists have postulated that consciousness is populations of neurons firing in certain brain areas, no more and no less. To most people, however, it seems bizarre to think that the distinctive tang of kumquats, say, is just a pattern of neural activation.

Our instincts about consciousness are triggered by specific cues, experimental philosophers explain, among them the existence of eyes and the appearance of goal-directed behavior, but not neurons. Studies indicate that people’s intuitions tell them that insects—which, of course, have eyes and show goal-directed behavior—can feel happiness, pain and anger.

The problem is that insects very likely lack the neural wherewithal for these sensations and emotions. What is more, engineers have programmed robots to display simple goal-directed behaviors, and these robots can produce the uncanny impression that they have feelings, even though the machines are not remotely plausible candidates for having awareness. In short, our instincts can lead us astray on this matter, too. Maybe consciousness does not have to be something different from—or above and beyond—brain processes.

Philosophical conflicts over such concepts as free will and consciousness often have their roots in ordinary intuitions, and the historical debates often end in stalemates. Experimental philosophers maintain that we can move past some of these impasses if we understand the nature of our gut feelings. This nascent field will probably not produce a silver bullet to fully restore or discredit our beliefs in free will and other potential illusions. But by understanding why we find certain philosophical views intuitively compelling, we might find ourselves in a position to recognize that, in some cases, we have little reason to hold onto our hunches.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Free will and mental disorder: Exploring the relationship

Gerben meynen.

Faculty of Philosophy and EMGO Institute, VU University Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1105, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands

A link between mental disorder and freedom is clearly present in the introduction of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). It mentions “an important loss of freedom” as one of the possible defining features of mental disorder. Meanwhile, it remains unclear how “an important loss of freedom” should be understood. In order to get a clearer view on the relationship between mental disorder and (a loss of) freedom, in this article, I will explore the link between mental disorder and free will. I examine two domains in which a connection between mental disorder and free will is present: the philosophy of free will and forensic psychiatry. As it turns out, philosophers of free will frequently refer to mental disorders as conditions that compromise free will and reduce moral responsibility. In addition, in forensic psychiatry, the rationale for the assessment of criminal responsibility is often explained by referring to the fact that mental disorders can compromise free will. Yet, in both domains, it remains unclear in what way free will is compromised by mental disorders. Based on the philosophical debate, I discuss three senses of free will and explore their relevance to mental disorders. I conclude that in order to further clarify the relationship between free will and mental disorder, the accounts of people who have actually experienced the impact of a mental disorder should be included in future research.

Introduction

A connection between mental disorder and freedom is clearly present in the introduction of the fourth edition to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). It reads, “In DSM-IV, each of the mental disorders is conceptualized as a clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in an individual and that is associated with present distress (e.g., a painful symptom)… or an important loss of freedom” [ 1 , p. xxi]. In this quotation, however, it remains unclear how “an important loss of freedom” should be understood. It could indicate practical impairments (like in physical illnesses) interfering with the freedom to live one’s life as preferred. Alternatively, “loss of freedom” may relate to the freedom of the mind or the concept of free will. In any case, the meaning of freedom within the context of the DSM-IV quotation remains unarticulated. This article seeks to explore the possible link between mental disorder and free will by looking at two domains in which such a link is clearly present: forensic psychiatry and the philosophy of free will.

The article consists of five parts. In the first section, the main themes of the current philosophical free will debate are discussed. Based on an account suggested by Henrik Walter, a distinction will be made between three senses of free will [ 2 ]. In the second section, it will turn out that, in fact, mental disorders often feature in the philosophical discussions on free will in the sense that persons are considered to be free and responsible unless they suffer from a mental disorder. In the third section, attention will be shifted to another domain, forensic psychiatry, in particular, to discussions on criminal responsibility. When a person performs a criminal act as a result of a mental disorder we intuit that this person is not responsible for the act. Why is this? In forensic literature, one type of answer to this question points to free will . In the fourth section, I will take stock of the discussions described in the first three sections. I will argue that, in both domains—philosophy of free will and forensic psychiatry—mental disorders are taken to be related to free will in a well-defined manner: they are considered to compromise free will and to reduce responsibility. Based on the previous sections, I explore the relevance of the three senses of free will with respect to mental disorders. In the fifth section, I will argue that in order to further clarify the relationship between free will and mental disorder, the accounts of people who have actually experienced the impact of a mental disorder should be included in future research.

Free will in current philosophical debates

Based on an account suggested by Walter, we can distinguish three main aspects, or components, of free will in the contemporary philosophical debate [ 2 ]. The first element is that to act freely, one must be able to act otherwise; one must have alternative possibilities open to one [ 3 ]. 1 If people cannot choose between alternatives because they are completely determined to act in a specific way (e.g., because of divine foreknowledge or because of the wiring of people’s brains), they cannot be said to act freely. Second, acting freely can also be understood as acting (or choosing) for a reason. Behavior that is not taking place for an intelligible reason is not considered “freely willed.” 2 For instance, hitting another person during an epileptic seizure, which does not occur for a reason, is not a free action, nor do we blame the person for such an action. Third, free will requires that one is the originator—(causal) source—of one’s actions. For instance, when an agent is being manipulated (or hypnotized) the agent cannot be said to act freely; although the agent performs the action, she is not the genuine source of it. The free will debate in philosophy is largely concerned with the question of to what extent each of these aspects is, indeed, essential to the concept of free will. 3 More precisely, at the moment, it is not clear which of these senses is pertinent to a notion of free will that is required for moral responsibility. In addition, we should note that these conceptions are certainly not exhaustive; there are various competing conceptions of free will [ 4 , 7 ]. Furthermore, each of these elements or senses of free will contains ambiguities, such as “(causal) source,” “person,” “ability to act,” and “acting for a reason.” The exact meaning that people attach to each of these might differ significantly. Sorting out these ambiguities probably hinges on people’s metaphysical and ethical commitments. For instance, being the source of an action can be explained in a libertarian account [ 3 , 6 ], but also in what can be considered a more naturalist account [ 8 ]. This being said, within the context of this article, the distinctions proposed by Walter provide a useful entrance to the complicated and multifaceted philosophical debate on free will.

A special case of the philosophical free will discussion is the compatibility problem. Philosophers have not been able to establish whether or not free will is compatible with determinism [ 4 ]. Determinism is the thesis that there is one physically possible future [ 9 ]. Whatever happens is inevitable or necessary because of, for example, fate, the will of God, or the laws of nature [ 5 ]. According to some people, the everyday “decisions” that we make in this world are basically in obedience to deterministic natural laws. Philosophers have not been able to reach consensus on whether free will can exist in such a deterministic world. The discussion on free will and determinism has not only taken place among philosophers; especially in the last decades, neuroscientists and psychologists have been participating in the debate also [ 2 – 4 , 10 ]. The compatibility debate has been going on for centuries. And in fact, not only determinism but also indeterminism appears to be problematic for free will, for what room would be left for free will, if everything happened by chance? [ 4 ]. Yet, the complexity of the concept of free will (and related issues) apparently has not undermined the value and significance attached to it by many. In this article, I will not take a specific position on whether free will is compatible with determinism.

But it is important to note a particular characteristic of free will: its relationship with moral responsibility. It appears that if anything is important to moral responsibility, it is free will [ 9 ]. Free will may be defined in many ways, but time after time, the central question is, does this specific concept of free will enable us to explain our moral intuitions? [ 11 ] As a result, in philosophy, discussions on moral responsibility (ethics) and free will (metaphysics) are deeply intertwined [ 4 , 11 ].

Free will and mental disorder in philosophical debates

Interestingly, mental disorders actually feature in philosophical discussions of free will and moral responsibility. Disorders like obsessive–compulsive disorder [ 2 ], kleptomania [ 12 ], addiction [ 13 ], and Tourette’s syndrome [ 14 ] are considered relevant to arguments about free will. Mental disorders and references to psychiatric signs and symptoms even feature in crucial papers that have shaped the debates on moral responsibility and free will over the last decades. Examples are Strawson’s Freedom and Resentment [ 15 ] and Frankfurt’s “Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person” [ 16 ]. In the latter paper, in order to explain a hierarchical account of freedom, Frankfurt describes an addict as a person who is not free. More precisely, on Frankfurt’s account, acting of one’s own free will implies that one wills the action and also wants to have the will to perform the action. An addict who has the will (or first order desire) to use heroin but who does not want to have this will is not free when using heroin. And in Watson’s interpretation of Frankfurt’s theory of responsibility, freedom should be perceived as a certain capacity people usually have, which “can be destroyed by addictions or phobias” [ 10 , p. 17].

Another example of the way in which mental disorders or psychopathological symptoms are used in the debate can be found in Galen Strawson:

Compatibilists believe that one can be a free and morally responsible agent even if determinism is true. Roughly, they claim, with many variations of detail, that one may correctly be said to be truly responsible for what one does, when one acts, just so long as one is not caused to act by any of a certain set of constraints (kleptomaniac impulses, obsessional neuroses, desires that are experienced as alien, post-hypnotic commands, threats, instances of force majeure , and so on). [ 17 , p. 222]

Apparently, kleptomanic impulses and obsessional neuroses can undermine free will and responsibility in this compatibilist account. Peter Strawson previously made an almost identical claim with respect to a certain compatibilist position:

What “freedom” means here is nothing but the absence of certain conditions the presence of which would make moral condemnation or punishment inappropriate. They [certain compatibilists] have in mind conditions like compulsion by another, or innate incapacity, or insanity, or other less extreme forms of psychological disorder. [ 15 , p. 73]

According to this view, both “insanity” and “less extreme forms of psychological disorder” undermine freedom to such an extent that moral condemnation is no longer appropriate. In the same vein, Widerker and McKenna state that “not all persons are morally responsible agents (such as small children, the severely mentally retarded, or those who suffer from extreme psychological disorder)…” [ 6 ]. According to Kalis et al., in the philosophy of free will, “[a]ddiction and compulsion are… presented as two different manifestations of the same thing—namely, unfree actions or actions caused by irresistible desires” [ 18 , p. 409]. And Watson states that “[a]ddiction… is commonly invoked as a kind of paradigm of unfree will” [ 10 , p. 20]. Meanwhile, with respect to alcoholism or “heavy drinking,” there are also other views. Herbert Fingarette, a philosopher with an interest both in free will/responsibility and mental disorders, for instance, is critical about the idea that heavy drinking or alcoholism (completely) undermines free will [ 19 ]. He starts out by writing that “[a]nyone who has ever observed the behavior of a chronic heavy drinker cannot help feeling a sense of momentum at work. In some way the inclination to down another drink seems to escape the full reach of rational judgment and of cool and deliberate free choice ” [ 19 , p. 32; emphasis added]. Yet, combining several strands of observations and research, Fingarette aims to prove that this view is, at least in part, falsified by empirical data by emphasizing that there is still (some form of) self-control present in alcoholism (e.g., people appear to be able to moderate their drinking in certain periods). This would imply that there is still a voluntary aspect preserved in heavy drinking, and that it does not involve an all-out loss of control and the ability to choose freely. 4

Daniel Levy, in a paper on free will and developments in cognitive neuroscience, zooms in on obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD): “We understand that a person suffering from obsessive–compulsive disorder, spending all day washing his hands and checking dozens of times that he remembered to lock the front door, cannot be thought of as having free will. His actions are mechanically dictated by stereotyped scripts, from which he cannot escape. Thus, obsessive–compulsive disorder is a malady of free will , because it prevents normal strategic planning and meta-control of behavior from overcoming compulsions” [ 20 , p. 214; emphasis added]. And Patricia Churchland apparently has a comparable opinion for she writes in a section on free choice and caused choice, “A patient with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) may have an overwhelming urge to wash his hands…. OCD patients often indicate that they wish to be rid of hand-washing or footstep counting behavior, but cannot stop. Pharmacological interventions, such as Prozac, may enable the subject to have what we would all regard as normal, free choice about whether or not to wash his hands” [ 21 , p. 208; emphasis added]. Finally, within the context of an argument on the requirement of alternative possibilities (one of the elements of free will mentioned earlier), Daniel Dennett even refers to fear of flying as an excusing condition [ 22 , p. 556]. This implies that more common mental traits like phobias have a bearing on responsibility.

As it appears, according to philosophers, mental disorder implies that free will and responsibility are compromised. Addiction and compulsion are kinds of disorders philosophers particularly refer to, but, in fact, all mental disorders, ranging from insanity to less extreme forms of psychological disorder, have some detrimental effect on free will and responsibility. 5 Meanwhile, what it is exactly that mental disorders do that leads to a suspension of freedom and responsibility remains unclear. Philosophers of free will seem to be primarily interested in describing responsibility and freedom in subjects whose free will and responsibility are not affected. Less attention has been paid to identifying the precise reasons why (certain) mental disorders would diminish free will; a detailed analysis of what it is that mental disorders do that has such an effect on free will is lacking. And while several of the quotations refer to mental disorders within the context of a compatibilist argument or view (which would mean that what mental disorders do to free will is explicable also in a deterministic world), it does not become clear how exactly the effect of mental disorder on free will should be understood in a deterministic world (Strawson and perhaps Wolf may be considered to provide the beginning of such an account [ 12 , 15 ]).

The topic of the next section is free will in forensic psychiatry, in particular, in theoretical reflections on the conceptual underpinnings of forensic assessment of criminal responsibility. It turns out that there are significant similarities between philosophical debates and forensic psychiatric views on free will and mental disorder.

Free will in forensic psychiatry

In legal procedures, forensic psychiatrists may be asked to assess the defendant with regard to criminal responsibility. For the court is not only interested in whether or not the defendant was the person who performed the legally relevant act but also in whether the defendant can be held accountable for that act. The issue at stake in such assessments is often referred to as “criminal responsibility.” Several legal criteria or rules have been established in order to assess criminal responsibility. The most influential is the M’Naghten Rule, which can be formulated as follows: “At the time of committing the act, the party accused was laboring under such a defect of reason, from the disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know what he was doing was wrong” [ 23 , p. 11]. Although the issue at stake is considered to be criminal responsibility, an area of dispute concerns the question, should forensic psychiatrists indeed express their view on whether the defendant is actually responsible (or not responsible) for the crime? Some hold that psychiatrists should not state whether or not a defendant is actually responsible or not; this judgment should be left to the jury or judge [ 24 ].

The legal rules, like the M’Naghten Rule, however, do not immediately answer the question, what basic moral notion makes us intuit that “diseases of the mind” have anything to do with accountability or responsibility? For instance, we intuit that the mother who kills her baby because of a delusional state in a postpartum psychosis is not morally and legally responsible for the act. She should be treated, not punished. Why? One important consideration explicitly refers to free will . A clear example is provided by Reich in Psychiatric Ethics . He states that “the law recognizes that insanity compromises free will, and classifies someone without free will as legally not responsible for his or her actions…” [ 25 , p. 206]. This understanding of the rationale for forensic assessments implies, at least according to Luthe and Rösler, that forensic psychiatrists “will have to concern themselves with the question of whether human actions can be freely chosen or whether the acting person could not avoid acting as he did.” [ 26 ]. Because of the perceived role of free will in forensic assessment, some theorists even consider the compatibility question to be relevant to forensic psychiatry [ 27 ]. Morse suggests that the idea among forensic practitioners that free will is a specific or foundational criterion for responsibility in morality and law is widespread [ 28 ]. 6 Such a view can lead forensic practitioners to refer to free will in their testimony before the court. They might say, for instance, that the defendant “lacked free will” and that, therefore , he or she is not accountable for the act.

In forensic practice, it is relevant that not all mental disorders are usually considered to be “candidates” for an insanity defense. Psychotic disorders, especially, are considered to have potentially decisive influence on human action [ 23 , 29 ]. However, there are no clear arguments that state that other mental disorders (other than psychosis) could not, in principle, provide grounds for an insanity defense [ 23 ].

In sum, the way in which free will is relevant to the forensic debate is in line with the way mental disorders are relevant to the philosophical debates on free will (see previous section). For the overall idea derived from the philosophy of free will is that—if anything—free will is required for moral responsibility and that free will can be compromised by mental disorder. This appears to be the line of thought present in the literature on forensic psychiatry as well. Yet, there also seems to be a difference between both domains. In forensic psychiatry the idea is clearly expressed that while mental disorders can , in certain cases, compromise free will, they do not necessarily undermine responsibility. Forensic assessment, therefore, is necessary not only in order to assess the presence of a mental disorder but also to assess the actual influence of the mental disorder on the agent’s acts. The mere presence of a mental disorder is certainly not sufficient for concluding that the defendant cannot be held accountable for the act. This view is less explicitly present in the philosophical debate.

Three senses of free will

As pointed out, given the current philosophical discussions, we can distinguish at least three senses of free will. Consequently, the sentence “mental disorders are able to compromise free will” can have different meanings. It could mean that mental disorders are able to undermine the agent’s ability to act otherwise, or that they can compromise his acting for intelligible reasons, or finally, it could mean that mental disorders may deprive a person from being the (causal) originator of the action. In what follows, mental disorder will be tentatively linked to each of these three different senses of free will.

Acting for (intelligible) reasons. Tics in Tourette’s syndrome (a neuropsychiatric disorder) are often considered to be performed without any reasons at all [ 30 ]. In such cases, people may flex their arms or utter sounds or words without any particular reason or motive. From the perspective of an “acting for reasons” view of free will, such a movement (which, in theory, can result in a criminal offense) is not performed freely. Also, in catatonia there may be movements for which there are no apparent reasons. For instance, there may be a stereotypical, repetitive behavior that does not seem to be explicable in terms of reasons [ 31 ]. 7 Yet, most mental disorders will not result in behavior for which no reason at all can be given. In fact, a characteristic of mental disorders is that, unlike many “somatic” disorders, they affect the intentional aspect of behavior. For example, a person who acts because of a paranoid delusion, acts for reasons influenced by a delusion: he killed his mother because he was convinced that she was continuously intoxicating him, and therefore, he wanted to stop her. So, on this account, except for, e.g., tics in Tourette’s and catatonic states, the criterion of “acting for reasons” per se will not lead to considering psychiatric disorders in general as potentially undermining free will. 8 (See also the next section on Tourette’s syndrome: not all tics are experienced as completely involuntary.)

The genuine source of the action (origination). Some might prefer to phrase this as “the person is the causal initiator of the action” (this conception is related to the philosophical position of source incompatibilism [ 6 ]). According to this view of free will, only actions whose source lies in the agent himself can be considered to be free actions. Now, actions performed because of delusions might not be considered to stem from the person himself . In fact, in forensic psychiatry it is sometimes said that the mental disorder caused the crime [ 32 ]. This idea of “mental disorder as the cause of an offense” provides room for the view that it was not the person himself who did it but that it was, instead, a mental disorder that caused the crime. The attribution of blame and responsibility, therefore, should not be directed at the person proper—for he or she is not the genuine source of the action. In one of the quotes from the philosophical debate (by Galen Strawson, see above) this can indeed be found: “just so long as one is not caused to act by… kleptomaniac impulses, obsessional neuroses” [ 17 , p. 222; emphasis added]. On this view, the person apparently is not the genuine source of the act in the sense that it was the mental disorder that caused the offense. For instance, consider an otherwise highly responsible person who is suffering from a bipolar disorder and who is convinced that he is entitled to harm innocent individuals, and via associative thinking, he comes up with a plan which results in a crime. Interpreting what occurred, we might say that during this manic episode, he was not “himself” and hence not responsible; he performed the act, but he was not performing it “freely” but as a result of a bipolar disorder. On such an account, the sense of free will as being the genuine source of the action might lead to considering acts resulting from (certain) mental disorders as “not free.”

Alternative possibilities. Are alternative possibilities for action or choice required for free will? [ 6 ]. This has been one of the thorniest issues in the philosophical free will debate, especially during the last decades. Meanwhile, in the forensic literature, alternative possibilities are mentioned as being compromised by mental disorder. For instance, Van Marle, a Dutch forensic psychiatrist, explaining forensic assessments in the Netherlands, states:

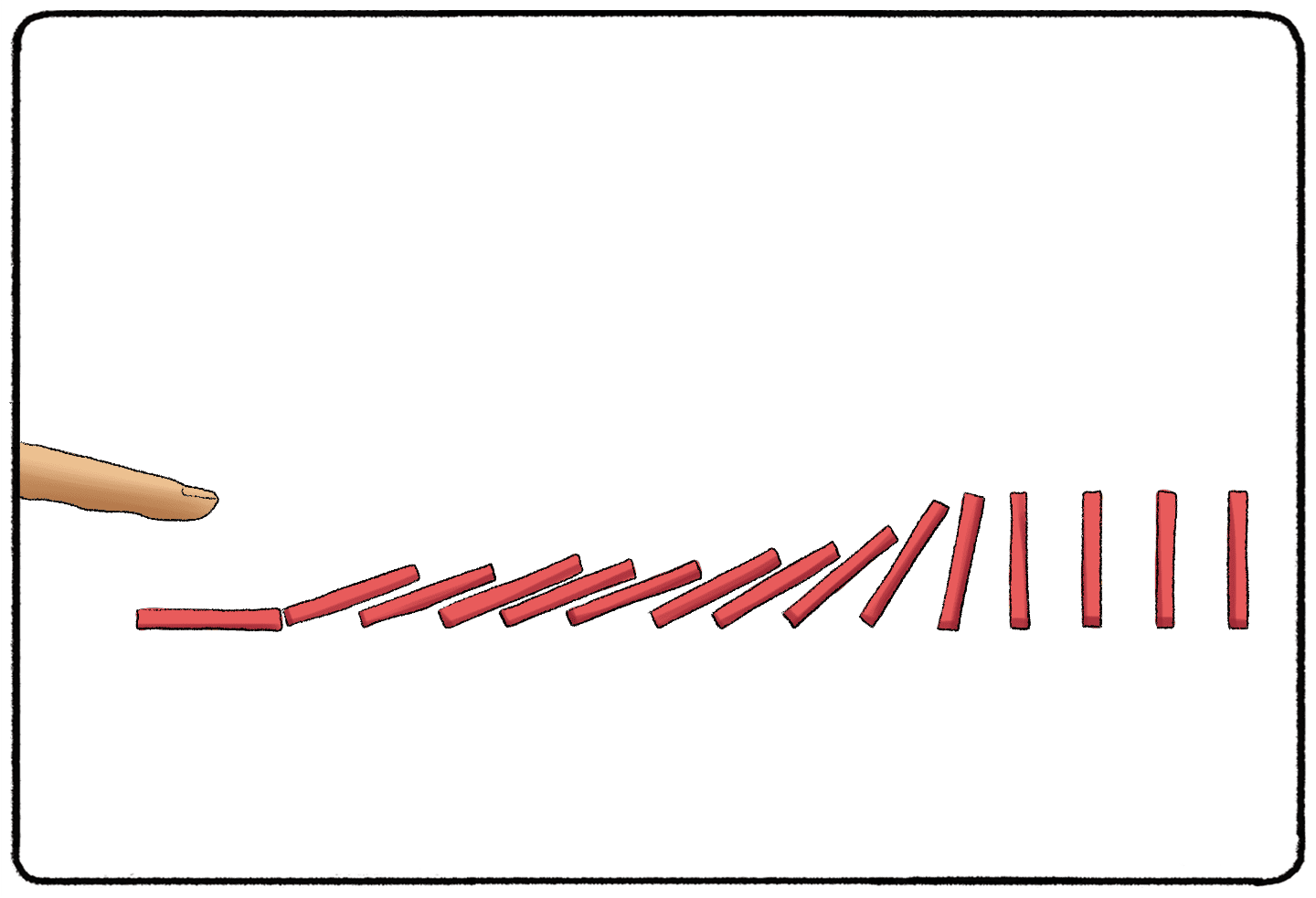

Undiminished responsibility means that the person concerned had complete access to his or her free will at the time of the crime with which he or she is charged and could therefore have chosen not to do it . Irresponsibility means that the person concerned had no free will at all with which to choose at the time of the crime with which he or she is charged. Important here is determining the moment when aspects of the disorder become manifest in the situation (“the scene of the crime”) that will eventually lead to the perpetration. The earlier they play a role, the more inevitable will be the (disastrous) sequence of events, and the stronger will be the eventual limitation of free will. [ 33 ; emphasis added]

The phrase “could therefore have chosen not to do it” implies, at least within this context, that mental disorders can undermine the possibility to choose between alternatives, and that this is why the person did not act freely. This also appears to be the case in the earlier quotes about OCD by Levy (“he cannot escape”) and Churchland (“OCD patients… cannot stop”)—both point to a lack of alternative possibilities. So, apparently, free will could be negated by mental disorder in that mental disorders may undermine the person’s ability to choose between alternatives. If this is taken to be the meaning of free will within the forensic context, we should note that this perspective also appears to be most directly vulnerable to attacks from (hard) deterministic views on free will, which claim that in our world, there are never any real alternatives. In addition, as mentioned above, compatibilist accounts of free will that do not rely on the element of alternative possibilities also express the idea that mental disorders undermine free will (see quotations from Galen and Peter Strawson above). This would imply that, at least in their (compatibilist) view, the alleged detrimental effect that mental disorders have on moral responsibility is not because they eliminate alternative possibilities.

In conclusion, there are different senses of free will, and, in principle, each of them could be relevant to the question of why mental disorders threaten responsibility. Each of the senses might also result in different answers to the question of whether free will is indeed undermined by certain mental disorders. Based on our preliminary considerations, one could understand the sentence “mental disorders are able to compromise free will” in terms of mental disorders undermining the person being the actual source of the action. This could make sense both from a forensic and philosophical perspective. Mental disorder, then, would affect the element of origination.

Apart from these senses of free will, there is the issue of degrees of freedom. It might be that various mental disorders result in different degrees of “compromised” free will. For instance, psychotic disorders appear to be the paradigm cases of compromised free will in forensic psychiatry [ 23 , 29 ], which suggests that their effects on free will are more pronounced than those of, e.g., obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). But is it indeed justified to look at these disorders in this way? Is the severity of the disorder proportionally related to the (alleged) influence on free action and free choice? Are mental disorders capable of undermining free will and responsibility irrespective of their severity? The philosophy of free will seems to suggest the latter, because “less extreme forms of psychological disorder” are also considered to be relevant to free will.

Theory and real people

So far, the exploration of the link between mental disorder and free will in this paper has been a theoretical endeavor. However, elucidating the relationship between mental disorder and free will and/or responsibility should not be a merely conceptual topic. It would be particularly interesting to qualitatively and quantitatively study the extent to which people who actually suffer(ed) from mental disorders experience(d) an effect on their free will and/or responsibility. Their accounts are remarkably absent from the philosophical and forensic discussions on free will and mental disorder; in general, philosophers, as well as forensic theorists, appear just to assume the (partial) absence of freedom in these conditions. However, outside the theoretical literature, we occasionally find brief accounts of people with mental disorders linking their condition to free will, like in the case of John in Best Possible Odds: Contemporary Treatment Strategies for Gambling Disorders : “John, a 38-year-old salesman, was being treated on an outpatient basis for a $1,000-a-week video poker gambling habit. As part of his sales job, he commuted by or near a number of video poker establishments. ‘Often,’ he noted, ‘I find them almost irresistible. It’s like I lose my free will when I am around them’” [ 34 , p. 138; emphasis added].

There are several reasons for the importance of a “first person” perspective on this matter. The first reason is that it is about psychopathological mental states. Such mental states are not easily accessible to everybody. Therefore, those who have had experiential access to these states or conditions should not be excluded from, but welcomed into, discussions on the relation between mental disorder, free will (in whatever sense), and responsibility. Notably, there are a huge variety of mental disorders, so being familiar with one of them is certainly not enough.

Second, an interesting study by Lang on movement disorders showed some surprising results with respect to “voluntariness” and certain psychopathological features [ 35 ]. It was long taken for granted that the tics in the neuropsychiatric Tourette’s syndrome were produced involuntarily. However, Lang aimed to determine the subjective perception patients have of abnormal movements by interviewing these patients on the “voluntary” versus “involuntary” aspects of their symptoms [ 35 ]. The majority of tic-disorder patients reported that their tics were voluntary; their motor and phonic tics were intentionally produced (this, of course, does not imply that these people want to have tics or Tourette’s syndrome, but it is, rather, about the specific nature or phenomenology of some of the tics and how their execution comes about [ 30 ]). Apart from the significance of this observation as such, there was an interesting practical implication of this finding. Because of the apparent intentional nature of some of the tics, it was hypothesized that cognitive behavioral therapy, especially the element of exposure and response prevention, might be beneficial. And, indeed, this kind of therapy has been used with at least some success to treat Tourette’s syndrome [ 30 ]. This indicates, first, that one can be surprised by the experience of “(in)voluntariness” reported by persons with a (neuro)psychiatric disorder and, second, that these reports can eventually result in the development of successful therapeutic interventions as well. So, we might be surprised by what people with OCD, addiction, and impulse-control disorders have to say about the “freedom” of their actions.

The third, though related reason concerns the fact that the discussion, as we have seen, apparently takes for granted that mental disorder is linked to reduced freedom. Now it might be that this basic view is not in line with actual experience, at least in some conditions. In fact, it might be that the kind of mental disturbance that intuitively appears to compromise “freedom” the most (e.g., manic or psychotic disorder) is not experienced as such by the person himself or herself during a psychotic episode. It would be interesting to ask people, not only during but also after the psychotic (delusional) episode, how they feel about their “free will” during the psychotic episode.

More precisely, examining “first person” reports may shed light on questions like the following: Are there perhaps specific symptoms that lead to the experience of a reduction in or loss of “free will”? Should free will as it relates to mental disorders be considered primarily as a matter of degree ? In principle, research aimed at systematically collecting and analyzing such first person accounts should cover the entire range of mental disorders, from phobias to psychotic disorders.

Given the fact that there is a significant lack of clarity about the nature of forensic assessment, getting a clearer view on the elements of the concept of free will that are potentially relevant to forensic assessments could help to clarify this psychiatric practice. This is especially important since this practice may have a profound impact on legal procedures and, therefore, on people’s lives. Still, we should consider the possibility that it is easier to (intuitively) know when free will is or is not present than it is to give an account of free will itself, and that, in a way, the former might be accomplished more effectively if we do not insist on linking it to the latter. Yet, as it is, forensic theorists and practitioners are actually already troubled by the topic of free will as it relates to the insanity defense [ 28 , 36 ]. More precisely, (at least some) forensic theorists and practitioners are concerned about the role of free will in forensic assessment in view of allegedly deterministic (e.g., neuroscientific) theories [ 28 ]. Given their concern, it might, for instance, be important to know whether mental disorder affects free will in a meaningful way in a deterministic world.

Although I have pointed to the relevance of empirical research on the experience of freedom in several mental disorders, conceptual issues also deserve further attention. As mentioned earlier, the framework of the three elements leaves ample room for questions and alternative interpretations. For instance, with respect to the person being the “genuine source of the action,” I mentioned that the mental disorder—rather than the “person proper”—could be considered the cause of a crime. Yet, this raises the question, what is the person proper and how can one distinguish the person proper from a mental disorder? This line of questioning will, sooner or later, bring up the question, what exactly is a mental disorder?—a central topic in the philosophy of psychiatry [ 37 ]. And if we focus on the “cause” of an event, then we must decide how to assess, among the manifold phenomena that contribute to the occurrence of a particular event (e.g., actions), which of these contributory phenomena count as an authentic “cause.” For instance, did an addict’s original decision to use heroin cause the heroin addiction and thus also cause the actions that subsequently resulted from the heroin addiction? In brief, a central issue will be, how do the person proper and the disorder relate and how can they be distinguished when it comes to the initiation of actions?

Within the medical domain, exploring the link between mental disorder and free will might not only be relevant with respect to forensic practice but also to questions about informed consent. Roberts clearly points to the role of “freedom” as a component of voluntarism in issues of informed consent: “Voluntarism involves the capacity to make this choice freely and in the absence of coercion” [ 38 , p. 707]. She also states, “Our understanding of voluntarism in this country is more intuitive and involves philosophical ideals of freedom, independence, personhood, and separateness” [ 38 , p. 705]. Moreover, she identifies mental illnesses and other psychological conditions as factors that may hamper voluntarism thus understood. Elucidating the relationship between mental disorder and matters of free will might therefore not only be beneficial to forensic discussions and to the philosophy of free will but, moreover, to other responsibility-related topics in which mental disorders play a role, like discussions on what it takes to obtain valid informed consent [ 39 ].

Finally, as mentioned before, while to some it might appear self-evident that mental disorders may compromise free will, we should not take that for granted. It is important, at least, to clarify whether mental disorder would invariably lead to some effect on free will or whether it is possible that a specific mental disorder does not affect free will at all. Notably, not considering people suffering from a mental disorder to be responsible agents (with respect to certain acts or decisions) might lead to a form of exclusion—which is always a risk with mental disorders [ 40 ]. On the other hand, holding persons responsible for behaviors that were, in fact, the result of a mental disorder, like postpartum psychosis, might also lead to forms of exclusion. Indeed, acknowledging that a certain behavior was the result of a temporary mental disorder and not due to the person’s own choice, so to speak, might even prevent that person from being excluded from the community.

In this paper the link between mental disorder and free will was explored as it is present in two domains: philosophy of free will and forensic psychiatry. As it turns out, philosophers working on free will often view mental disorders as compromising free will and, hence, as threatening or reducing responsibility. In forensic psychiatry, mental disorders are also viewed as compromising the agent’s free will and legal responsibility. Meanwhile, in philosophy, free will turns out to be hard to define. However, three central elements or senses of free will are present in the philosophical debate. Consequently, the sentence “mental disorders are able to compromise free will” can have at least three different meanings. In order to explore the link between mental disorder and free will, we tentatively related each of these three senses to mental disorder. Based on our preliminary considerations, understanding the sentence in terms of the mental disorder preventing the person from being the actual source of the action could make sense both from a forensic and a philosophical perspective. Mental disorder, then, would affect the element of origination.

Returning to the “important loss of freedom” phrase in the introduction of the DSM-IV, which motivated this article, I conclude that freedom in the sense of free will could indeed be a meaningful understanding of this phrase. Both the philosophical debate on free will and forensic psychiatry suggest that mental disorders may affect free will. Yet, the sense of free will that may be affected by mental disorder in general and by specific disorders in particular remains to be elucidated. It is, therefore, important to further study this link, especially because of the value attached to free action and free decision-making in the lives of individual people and because of the impact of (not) ascribing praise and blame to an agent. It is noteworthy that the mental states associated with mental disorders are not immediately accessible to everybody. Therefore, further research should not only be conceptual in nature but also involve first person and firsthand accounts of people who actually suffered or suffer from mental disorder. Their experiences should inform the discussion on free will and mental disorder.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, Grant 275-20-016. I thank Prof. David Widerker for his helpful suggestions.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

1 Walter describes these three “features,” or “components,” of the philosophical debate on free will while acknowledging that not all philosophical theories agree on these three elements: “Those various theories differ solely in the fact,” Walter claims, “that they either deal only with part of the components, or they declare one of them to be particularly significant, or they support variously strong interpretations” [ 2 , p. 6]. Within the framework of this article, I consider these three elements of the philosophical debate as three senses of free will. See also the “ Three sense of free will ” section for further discussion on these senses.

2 Walter provides the following definition of the component of intelligible action (acting for reasons): “A person acts (wants, decides, chooses) intelligibly, if she at least partially mentally represents alternatives and their possible consequences, apprehends their meanings, and using this knowledge actively realizes one of the alternatives for reasons which are—in principle—inducible to insight” [ 2 , p. 31]. This implies that the expression “acting for a reason” is not to be understood merely as asserting that there is an explanation of some kind for the agent’s conduct .

3 We have to note that in philosophical debates, “free will,” “freedom of the will,” and “personal freedom” are often used interchangeably (see, e.g., Kane [ 4 , 5 ] and Widerker and McKenna [ 6 ]).

4 Meanwhile, it is important to note that Fingarette doesn’t consider alcoholism to be a psychopathological condition [ 19 ].

5 Although, based on Fingarette’s account, one could challenge this view with respect to alcohol addiction.

6 It should be noted that not everyone is convinced that free will is essential to forensic assessment (see, e.g., [ 28 ]). Meanwhile, given the focus of this article, I will concentrate on the perspective on forensic assessment in which free will is relevant.

7 We have to note that both Tourette’s syndrome and catatonia may also be relevant to both of the other senses of free will (being the genuine source of the action and having alternative possibilities).

8 In my account of “acting for understandable reasons,” I emphasize the fact that actions are performed for reasons as such. Walter mentions “acting for understandable reasons” in order to grasp the notion of intelligibility [ 2 , p. 31] . If one would emphasize, however, the understandability of the reasons with respect to actions stemming from mental disorder (for instance in case of delusional behavior), this might well lead to a different conclusion in the sense that the reasons behind actions stemming from mental disorders may not always be (easily or fully) understandable.

Free Will vs Determinism (Debate in Psychology)

Do you believe in free will? Do you freely choose to make all of your decisions?

These are some big questions, and the answers from philosophers and psychologists may upset you. And it won’t help if I tell you that your upset feelings are not something that you chose to feel, either.

But that's the nature of psychology's biggest debate: free will and determinism.

What Is Free Will Vs. Determinism?

Psychologists have spent centuries debating how much control humans have over their thoughts, emotions, and actions. On one side of the spectrum is complete free will; on the other side is a world where everything is determined for us before it happens.

What Is Free Will?

You may have heard the term “free will” before. It comes up quite a bit in the Christian religion - many Christians are taught that God gave them the free will to sin or not to sin. In psychology and philosophy, free will isn’t a gift from God but just how the world operates.

Examples of Free Will

We feel free when we decide to go to the park or buy a new backpack. After all, we had the options of going to the swimming pool or saving our money. Free will is the ability to make a choice when other options are present. Nothing is predetermined. Instead, we create our own destiny and have the power to make any decision at any given time.

Can Free Will and Determinism Coexist?

You may believe that free will cannot exist in a deterministic universe. You may believe that free will and determinism are completely separate and that free will reigns supreme. In this case, you would consider yourself a libertarian free will. (This has nothing to do with the political party.)

However, it’s easy to argue that free will doesn’t really extend beyond human behavior. Certain chemicals will react when they interact with other chemicals - they don’t have the free will to do otherwise. When lightning strikes, thunder doesn’t have the option of taking the day off. All of these physical factors could also limit our choices.

But according to free will, there is a difference between physical causation and agent causation. Not everything is completely random, however, we have the ability to take control (as an agent) and start a new causal chain of events.

As you’ll learn, it’s easy to argue against free will. But there is certainly something to be said for the fact that when we decide to go skateboarding or have breakfast for dinner, we feel like we are in complete control.

But are we?

What Is Determinism?

Now let’s talk about determinism. If free will lives on one end of a spectrum, determinism lives at the completely opposite end. Determinism is the idea that we have no control over our actions. Instead, internal and external factors determine the choices that we make. Our behavior is completely predictable. We have no sense of personal responsibility, because all of our actions are dictated by other things.

Some of the things that cause is to act are external: weather, media, our parents, etc. Some of these things are internal. We’ll go more into that a bit later.

This can make us feel uncomfortable, sure. But start to think about some of the decisions you made in the past week. Were they caused by something before it? Most likely, yes. Maybe you decided not to play baseball because it was raining outside or because you left your cleats at a friend’s house. Or you left a party early because your stomach hurt. You paid rent because you signed a lease because you were taught that it was important to live in a home.

Studies on Determinism in Psychology

The causes of our actions can go all the way back to our childhood. Take Bandura’s Bobo Doll experiment . Children either observed an adult hitting a Bobo doll or being gentle with the Bobo Doll. The children did not choose which adult they would be observing. The children who observed the aggressive adult were more likely to be aggressive. This experiment was one of many that shaped Behaviorism and linked the “cause” of certain actions and behaviors to conditioning. Ivan Pavlov was able to make dogs uncontrollably drool through conditioning. What have we been conditioned to do?

What Causes Determinism?

There are a few factors that you can play around with to pinpoint the causes of your actions and decisions. Some psychologists believe that your actions are caused by a combination of factors, including:

- Temperaments

Let’s use the example of buying a backpack. You believe that a backpack would be a worthy investment and that it is superior to another type of bag. You desire a backpack for yourself after carrying around a ripped bag and seeing everyone at work with nice backpacks. At the time you decide to buy, your temperament is pleasant and you’re in the mood to do some shopping.

A similar theory about our decisions and prompts can be found in Tiny Habits. This book, written by Stanford researcher BJ Fogg, discusses his Behavior Model. He believes behaviors are caused by:

It’s easy to see the similarities between these two.

Different Levels of Determinism

If you’ve been on my page before, you know how powerful beliefs are. You also know that it’s entirely possible to change your beliefs and change the course of your life. Are these changes also pre-determined, or are they something that we can control through free will?

You don’t have to answer that by choosing one end of the spectrum. There are ideas that blend both free will and determinism to form theories that aren’t so extreme.

Soft Determinism

One of these ideas is soft determinism. Soft determinism is the idea that all of our actions are predetermined or self-determined. The difference is that self-determined actions, or actions caused by internal factors, are considered free. If you believe that the choice to knock out limiting beliefs is your choice, then you probably feel more comfortable with the idea of soft determinism.

Compatibilism

The idea that free will and determinism can exist together is called compatibilism. When thinking about our ability to make our own choices versus the choices that are pre-determined for us, compatibilism seems like a feel-good compromise. But it doesn’t always help philosophers and psychologists when thinking about responsibility. When are we responsible for our actions? Can internal factors, like a mental illness or intoxication, free us from responsibility? How does that work when someone chooses to alter these factors? Or did they really make that choice in the first place?

We Don't Have All the Answers

Want to hear more thoughts on free will vs. determinism? Psychologists, philosophers, and even Reddit users continue to weigh into this debate.

Quotes on Free Will and Determinism

- "Man, what are you talking about? Me in chains? You may fetter my leg but my will, not even Zeus himself can overpower.” -Epictetus

- "Though I cannot tell why it was exactly that those stage managers, the Fates, put me down for this shabby part of a whaling voyage, when others were set down for magnificent parts in high tragedies, and short and easy parts in genteel comedies, and jolly parts in faces—though I cannot tell why this was exactly; yet, now that I recall all the circumstances, I think I can see a little into the springs and motives which being cunningly presented to me under various disguises, induced me to set about performing the part I did, besides cajoling me into the delusion that it was a choice resulting from my own unbiased freewill and discriminating judgment.” - Herman Melville, Moby Dick

- "For we do not run to Christ on our feet but by faith; not with the movement of the body, but with the freewill of the heart. Think not that thou art drawn against thy will: the mind can be drawn by love.” - Augustine of Hippo

- "Humans have an amazing capacity to believe in contradictory things. For example, to believe in an omnipotent and benevolent God but somehow excuse Him from all the suffering in the world. Or our ability to believe from the standpoint of law that humans are equal and have free will and from biology that humans are just organic machines." - Yuval Noah Harari

The Debate Continues On Reddit!

Below are just a few thoughts from Reddit users on the entp subreddit!

u/Destrh0 said :

" There is no such thing as actual free will, only a remarkable facsimile of free will. At our core, we are truly unable to make any completely free choice. It is tantamount to being able to make a completely random decision. We aren't even consciously aware of any decision being made until well after it has been made. And anyone with severe PTSD will tell you that they really don't have a choice in a lot of their reactions. Free will is a joke."

They were met with a rebuttal from u/ENTP-one: " I actually thought about it a lot lately. I come up with an thesis that to stop everything being pre descent you have to do something only from the need of changing the path. If your 100% you want to do something not doing it and choosing something that you 100% not wanna do will change the destination. Of course the idea only works if what's predestination does not account for you knowing it and actively doing something just to mess it up. But at the moment you do it the new path is created and again we are stuck in this predestined path."

u/Musikcookie said:

"I believe in both. Humans have this weird conception, that free will would somehow be apart from the world it exits. But what would this even mean? Even apart from our world a free will will have to be based on what happens in this world, so it would still run into the same problems. This is because a free will needs to have some sort of logic to it. If we stop setting unreasonably high bars for what a “free will” has to accomplish, we can see, that our complex ability to change things can pass as a free will."

u/fridge_escaped said:

"I have to do what any self-respecting ENTP would do, when proposed two options: provide a third (albeit popular one). I believe that we have both, but on different scales. From my surface knowledge of statistical mechanics and chaos theory even in completely chaotic environment we can define a trend, which the system follows, but locally its actions could be totally non-deterministic. So we have an option to choose what path to take, but in the end most of this choices lead us to singular ending.

Quick tangent there: we are always "governed by internal or external forces we cannot control" - physics provides tons of examples. I think what matters is what you do in the face of circumstances you cannot change. You can always settle for obvious options and weep "The system is rigged!", or you can try to find/make a way. Isn't it who we are?"

Want to read the whole debate? You can, on Reddit!

There is a lot to unpack when we think about free will and determinism. There is no definite answer that everyone can agree on. But that is why we continue to observe behavior, conduct experiments, and study how humans behave and make choices.

Related posts:

- William Glasser Biography - Contributions To Psychology

- Choice Theory (Definition + Examples)

- The Mind Body Debate in Psychology

- Behavioral Psychology

- Albert Bandura (Biography + Experiments)

Reference this article:

About The Author

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Free will is the idea that humans have the ability to make their own choices and determine their own fates. Is a person’s will free, or are people's lives in fact shaped by powers outside of their control? The question of free will has long challenged philosophers and religious thinkers, and scientists have examined the problem from psychological and neuroscientific perspectives as well.

- Does Free Will Exist?

- Why Beliefs About Free Will Matter

Scientists have investigated the concept of human agency at the level of neural circuitry, and some findings have been taken as evidence that conscious decisions are not truly “free.” Free will skeptics argue that the subjective sense of free will is an illusion. Yet many scholars, as well as ordinary people, still profess a belief in free will, even if they acknowledge that choices are partly shaped by forces outside of one's control.

Behavioral science has made plain that individuals’ behavioral tendencies are influenced by genetics , as well as by factors in the environment that may be outside of a person’s control. This suggests that there are, at least, some constraints on the range of decisions and behaviors a person will be inclined to make (or even to consider) in any given situation. Challengers of the idea that people act the way they do due to conscious, unconstrained choices also point to evidence that unconscious brain activity can partly predict a choice before a conscious decision is made. And some have sought to logically refute the argument that choices necessarily demonstrate free will.

While there are many reasons to believe that a person’s will is not completely free of influence, there is not a scientific consensus against free will. Some use the term “free will” in a looser sense to reflect that conscious decisions play a role in the outcomes of a person’s life—even if those are shaped by innate dispositions or randomness. (Critics of the concept of free will might simply call this kind of decision-making “will,” or volition.) Even when unconscious processes help determine a person’s conscious behavior, some argue, such processes can still be thought of as part of an individual’s will.

Determinism is the idea that every event, including every human action, is the result of previous events and the laws of nature. A belief in determinism that includes a rejection of free will has been called “hard determinism.”

From a deterministic perspective, there is only one possible way that future events can unfold based on what has already occurred and the rules that govern the universe—though that doesn’t mean such events can necessarily be predicted by humans. Someone who believes in free will because they do not take determinism for granted is called, in philosophy , a “libertarian.”

Yes. This is called “compatibilism” or “soft determinism.” A compatibilist believes that even though events are predetermined, there is still some version of free will at work in decision-making . An incompatibilist argues that only determinism or free will can be true.

Whether free will exists or not, belief in free will is very real. Does it matter if a person believes that her choices are completely her own, and that other people’s choices are freely made, too? Psychologists have explored the connections between free will beliefs—often gauged by agreement with statements like “I am in charge of my actions even when my life’s circumstances are difficult” and, simply, “I have free will”—and people’s attitudes about decision-making, blame, and other variables of consequence.

The more people agree with claims of free will , some research suggests, the more they tend to favor internal rather than external explanations for someone else’s behavior. This may include, for example, learning of someone’s immoral deed and agreeing more strongly that it was a result of the person’s character and less that factors like social norms are to blame. (A study of whether reducing free-will beliefs influenced sentencing decisions by actual judges, however, did not show any effect. )

One idea proposed in philosophy is that systems of morality would collapse without a common belief that each person is responsible for his actions—and thus deserves reward or punishment for them. In this view, there is value in maintaining belief in free will, even if free will is in fact an illusion. Others argue that morality can exist in the absence of free-will belief, or that belief in free will actually promotes harmful outcomes such as intolerance and revenge-seeking. Some psychology research has been cited as suggesting that disbelief in free will increases dishonest behavior, but subsequent experiments have called this finding into question.

Mental illness can be thought of, in a sense, as involving additional constraints on the freedom of a person’s will (in the form of rigid thought patterns or compulsions, for instance), beyond the usual factors that shape thinking and behavior. Belief in free will, it has been argued, may contribute to the stigma attached to mental illness by obscuring the role of underlying biological and environmental causes.

There is limited evidence that people who believe more strongly in free will may tend to perceive at least some kinds of choices—such as buying electronics or deciding what to watch on TV—as easier to make, and that they may enjoy making choices more.

Two concepts from psychology that bear similarity to belief in free will are “ locus of control ” and “ self-efficacy .” Locus of control refers to a person’s belief about how much power he has over his life—how important factors like intentions and hard work seem to be compared to external forces such as good luck or the actions of others. Self-efficacy is a person’s sense of her ability to perform at a certain level so as to influence events that affect them. While all of these concepts relate to the factors that steer a person’s life, they are distinct—one can doubt that humans have free will, for example, and still be confident in her ability to win a competition .

The brain has three processing stages associated with consciousness. Here, we focus on Stage 2, "the conscious field."

There are three stages of processing in the brain, starting with unconscious processes preceding, and giving rise to, the construction of the “conscious field."

Algorithms are designed to keep your attention engaged and programmed to be passive and predictable. Fortunately, mindfulness connects you to this moment with joy and spontaneity.

As their child's adolescent transformation begins, parents can feel helpless in the face of developmental change, but they still have many sources of influence to draw upon.

This post explores a different way to view the trendy topic of gut health by exploring the gut-brain connection and how to trust your gut with greater confidence.

People have "sold their soul" in books, songs, and even real life. For a non-believer a soul is worth $0 — but how much should a believer pay for one?

When smart people looking at the same evidence disagree, the reason might be that they define basic concepts differently and talk past each other.

That little voice inside your head? The puzzle of consciousness would still be there without it. Here's why.

As initiatives are discussed surrounding involuntary psychiatric care, an important element is ignored. The quality of treatment in the hospital is often poor.

What is life calling out to you?

- Find Counselling

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United Kingdom

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Free will is the idea that humans have the ability to make their own choices and determine their own fates. Is a person’s will free, or are people's lives in fact shaped by powers outside of...

Free will is the idea that we are able to have some choice in how we act and assumes that we are free to choose our behavior. In other words, we are self-determined. For example, people can make a free choice as to whether to commit a crime or not (unless they are a child or they are insane).

In order to better understand the neural bases of free will, provided that there are any, in this article I’ll review and integrate findings from studies in different fields (philosophy, cognitive neuroscience, experimental and clinical psychology, neuropsychology).

Your free will, he suggests, shines when you resist temptation and do what is in your own long-term interest (salvation) or in the interest of the group (conformity, obedience). This view...

research on free will disbelief, especially within social psychology, for committing methodological errors and misinterpreting findings, leading to overblown and unwarranted concerns about free will skepticism and disbelief.

November 1, 2011. 5 min read. Is Free Will an Illusion? Don't trust your instincts about free will or consciousness, experimental philosophers say. By Shaun Nichols. November 2011 Issue....

I examine two domains in which a connection between mental disorder and free will is present: the philosophy of free will and forensic psychiatry. As it turns out, philosophers of free will frequently refer to mental disorders as conditions that compromise free will and reduce moral responsibility.

There is a long philosophical tradition of treating free will as the set of capacities that, when properly functioning, allow us to make decisions that contribute to a good or flourishing life. On this view, free will is a psychological accomplishment.

Do humans have free will? Are our actions pre-determined? Psychologists still go back and forth on the free will vs. determinism debate.

Free will is the idea that humans have the ability to make their own choices and determine their own fates. Is a person’s will free, or are people's lives in fact shaped by powers outside...