- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Research Summary

It’s a common perception that writing a research summary is a quick and easy task. After all, how hard can jotting down 300 words be? But when you consider the weight those 300 words carry, writing a research summary as a part of your dissertation, essay or compelling draft for your paper instantly becomes daunting task.

A research summary requires you to synthesize a complex research paper into an informative, self-explanatory snapshot. It needs to portray what your article contains. Thus, writing it often comes at the end of the task list.

Regardless of when you’re planning to write, it is no less of a challenge, particularly if you’re doing it for the first time. This blog will take you through everything you need to know about research summary so that you have an easier time with it.

What is a Research Summary?

A research summary is the part of your research paper that describes its findings to the audience in a brief yet concise manner. A well-curated research summary represents you and your knowledge about the information written in the research paper.

While writing a quality research summary, you need to discover and identify the significant points in the research and condense it in a more straightforward form. A research summary is like a doorway that provides access to the structure of a research paper's sections.

Since the purpose of a summary is to give an overview of the topic, methodology, and conclusions employed in a paper, it requires an objective approach. No analysis or criticism.

Research summary or Abstract. What’s the Difference?

They’re both brief, concise, and give an overview of an aspect of the research paper. So, it’s easy to understand why many new researchers get the two confused. However, a research summary and abstract are two very different things with individual purpose. To start with, a research summary is written at the end while the abstract comes at the beginning of a research paper.

A research summary captures the essence of the paper at the end of your document. It focuses on your topic, methods, and findings. More like a TL;DR, if you will. An abstract, on the other hand, is a description of what your research paper is about. It tells your reader what your topic or hypothesis is, and sets a context around why you have embarked on your research.

Getting Started with a Research Summary

Before you start writing, you need to get insights into your research’s content, style, and organization. There are three fundamental areas of a research summary that you should focus on.

- While deciding the contents of your research summary, you must include a section on its importance as a whole, the techniques, and the tools that were used to formulate the conclusion. Additionally, there needs to be a short but thorough explanation of how the findings of the research paper have a significance.

- To keep the summary well-organized, try to cover the various sections of the research paper in separate paragraphs. Besides, how the idea of particular factual research came up first must be explained in a separate paragraph.

- As a general practice worldwide, research summaries are restricted to 300-400 words. However, if you have chosen a lengthy research paper, try not to exceed the word limit of 10% of the entire research paper.

How to Structure Your Research Summary

The research summary is nothing but a concise form of the entire research paper. Therefore, the structure of a summary stays the same as the paper. So, include all the section titles and write a little about them. The structural elements that a research summary must consist of are:

It represents the topic of the research. Try to phrase it so that it includes the key findings or conclusion of the task.

The abstract gives a context of the research paper. Unlike the abstract at the beginning of a paper, the abstract here, should be very short since you’ll be working with a limited word count.

Introduction

This is the most crucial section of a research summary as it helps readers get familiarized with the topic. You should include the definition of your topic, the current state of the investigation, and practical relevance in this part. Additionally, you should present the problem statement, investigative measures, and any hypothesis in this section.

Methodology

This section provides details about the methodology and the methods adopted to conduct the study. You should write a brief description of the surveys, sampling, type of experiments, statistical analysis, and the rationality behind choosing those particular methods.

Create a list of evidence obtained from the various experiments with a primary analysis, conclusions, and interpretations made upon that. In the paper research paper, you will find the results section as the most detailed and lengthy part. Therefore, you must pick up the key elements and wisely decide which elements are worth including and which are worth skipping.

This is where you present the interpretation of results in the context of their application. Discussion usually covers results, inferences, and theoretical models explaining the obtained values, key strengths, and limitations. All of these are vital elements that you must include in the summary.

Most research papers merge conclusion with discussions. However, depending upon the instructions, you may have to prepare this as a separate section in your research summary. Usually, conclusion revisits the hypothesis and provides the details about the validation or denial about the arguments made in the research paper, based upon how convincing the results were obtained.

The structure of a research summary closely resembles the anatomy of a scholarly article . Additionally, you should keep your research and references limited to authentic and scholarly sources only.

Tips for Writing a Research Summary

The core concept behind undertaking a research summary is to present a simple and clear understanding of your research paper to the reader. The biggest hurdle while doing that is the number of words you have at your disposal. So, follow the steps below to write a research summary that sticks.

1. Read the parent paper thoroughly

You should go through the research paper thoroughly multiple times to ensure that you have a complete understanding of its contents. A 3-stage reading process helps.

a. Scan: In the first read, go through it to get an understanding of its basic concept and methodologies.

b. Read: For the second step, read the article attentively by going through each section, highlighting the key elements, and subsequently listing the topics that you will include in your research summary.

c. Skim: Flip through the article a few more times to study the interpretation of various experimental results, statistical analysis, and application in different contexts.

Sincerely go through different headings and subheadings as it will allow you to understand the underlying concept of each section. You can try reading the introduction and conclusion simultaneously to understand the motive of the task and how obtained results stay fit to the expected outcome.

2. Identify the key elements in different sections

While exploring different sections of an article, you can try finding answers to simple what, why, and how. Below are a few pointers to give you an idea:

- What is the research question and how is it addressed?

- Is there a hypothesis in the introductory part?

- What type of methods are being adopted?

- What is the sample size for data collection and how is it being analyzed?

- What are the most vital findings?

- Do the results support the hypothesis?

Discussion/Conclusion

- What is the final solution to the problem statement?

- What is the explanation for the obtained results?

- What is the drawn inference?

- What are the various limitations of the study?

3. Prepare the first draft

Now that you’ve listed the key points that the paper tries to demonstrate, you can start writing the summary following the standard structure of a research summary. Just make sure you’re not writing statements from the parent research paper verbatim.

Instead, try writing down each section in your own words. This will not only help in avoiding plagiarism but will also show your complete understanding of the subject. Alternatively, you can use a summarizing tool (AI-based summary generators) to shorten the content or summarize the content without disrupting the actual meaning of the article.

SciSpace Copilot is one such helpful feature! You can easily upload your research paper and ask Copilot to summarize it. You will get an AI-generated, condensed research summary. SciSpace Copilot also enables you to highlight text, clip math and tables, and ask any question relevant to the research paper; it will give you instant answers with deeper context of the article..

4. Include visuals

One of the best ways to summarize and consolidate a research paper is to provide visuals like graphs, charts, pie diagrams, etc.. Visuals make getting across the facts, the past trends, and the probabilistic figures around a concept much more engaging.

5. Double check for plagiarism

It can be very tempting to copy-paste a few statements or the entire paragraphs depending upon the clarity of those sections. But it’s best to stay away from the practice. Even paraphrasing should be done with utmost care and attention.

Also: QuillBot vs SciSpace: Choose the best AI-paraphrasing tool

6. Religiously follow the word count limit

You need to have strict control while writing different sections of a research summary. In many cases, it has been observed that the research summary and the parent research paper become the same length. If that happens, it can lead to discrediting of your efforts and research summary itself. Whatever the standard word limit has been imposed, you must observe that carefully.

7. Proofread your research summary multiple times

The process of writing the research summary can be exhausting and tiring. However, you shouldn’t allow this to become a reason to skip checking your academic writing several times for mistakes like misspellings, grammar, wordiness, and formatting issues. Proofread and edit until you think your research summary can stand out from the others, provided it is drafted perfectly on both technicality and comprehension parameters. You can also seek assistance from editing and proofreading services , and other free tools that help you keep these annoying grammatical errors at bay.

8. Watch while you write

Keep a keen observation of your writing style. You should use the words very precisely, and in any situation, it should not represent your personal opinions on the topic. You should write the entire research summary in utmost impersonal, precise, factually correct, and evidence-based writing.

9. Ask a friend/colleague to help

Once you are done with the final copy of your research summary, you must ask a friend or colleague to read it. You must test whether your friend or colleague could grasp everything without referring to the parent paper. This will help you in ensuring the clarity of the article.

Once you become familiar with the research paper summary concept and understand how to apply the tips discussed above in your current task, summarizing a research summary won’t be that challenging. While traversing the different stages of your academic career, you will face different scenarios where you may have to create several research summaries.

In such cases, you just need to look for answers to simple questions like “Why this study is necessary,” “what were the methods,” “who were the participants,” “what conclusions were drawn from the research,” and “how it is relevant to the wider world.” Once you find out the answers to these questions, you can easily create a good research summary following the standard structure and a precise writing style.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing Guide

Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Findings

Definition:

Research findings refer to the results obtained from a study or investigation conducted through a systematic and scientific approach. These findings are the outcomes of the data analysis, interpretation, and evaluation carried out during the research process.

Types of Research Findings

There are two main types of research findings:

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative research is an exploratory research method used to understand the complexities of human behavior and experiences. Qualitative findings are non-numerical and descriptive data that describe the meaning and interpretation of the data collected. Examples of qualitative findings include quotes from participants, themes that emerge from the data, and descriptions of experiences and phenomena.

Quantitative Findings

Quantitative research is a research method that uses numerical data and statistical analysis to measure and quantify a phenomenon or behavior. Quantitative findings include numerical data such as mean, median, and mode, as well as statistical analyses such as t-tests, ANOVA, and regression analysis. These findings are often presented in tables, graphs, or charts.

Both qualitative and quantitative findings are important in research and can provide different insights into a research question or problem. Combining both types of findings can provide a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon and improve the validity and reliability of research results.

Parts of Research Findings

Research findings typically consist of several parts, including:

- Introduction: This section provides an overview of the research topic and the purpose of the study.

- Literature Review: This section summarizes previous research studies and findings that are relevant to the current study.

- Methodology : This section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used in the study, including details on the sample, data collection, and data analysis.

- Results : This section presents the findings of the study, including statistical analyses and data visualizations.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results and explains what they mean in relation to the research question(s) and hypotheses. It may also compare and contrast the current findings with previous research studies and explore any implications or limitations of the study.

- Conclusion : This section provides a summary of the key findings and the main conclusions of the study.

- Recommendations: This section suggests areas for further research and potential applications or implications of the study’s findings.

How to Write Research Findings

Writing research findings requires careful planning and attention to detail. Here are some general steps to follow when writing research findings:

- Organize your findings: Before you begin writing, it’s essential to organize your findings logically. Consider creating an outline or a flowchart that outlines the main points you want to make and how they relate to one another.

- Use clear and concise language : When presenting your findings, be sure to use clear and concise language that is easy to understand. Avoid using jargon or technical terms unless they are necessary to convey your meaning.

- Use visual aids : Visual aids such as tables, charts, and graphs can be helpful in presenting your findings. Be sure to label and title your visual aids clearly, and make sure they are easy to read.

- Use headings and subheadings: Using headings and subheadings can help organize your findings and make them easier to read. Make sure your headings and subheadings are clear and descriptive.

- Interpret your findings : When presenting your findings, it’s important to provide some interpretation of what the results mean. This can include discussing how your findings relate to the existing literature, identifying any limitations of your study, and suggesting areas for future research.

- Be precise and accurate : When presenting your findings, be sure to use precise and accurate language. Avoid making generalizations or overstatements and be careful not to misrepresent your data.

- Edit and revise: Once you have written your research findings, be sure to edit and revise them carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, make sure your formatting is consistent, and ensure that your writing is clear and concise.

Research Findings Example

Following is a Research Findings Example sample for students:

Title: The Effects of Exercise on Mental Health

Sample : 500 participants, both men and women, between the ages of 18-45.

Methodology : Participants were divided into two groups. The first group engaged in 30 minutes of moderate intensity exercise five times a week for eight weeks. The second group did not exercise during the study period. Participants in both groups completed a questionnaire that assessed their mental health before and after the study period.

Findings : The group that engaged in regular exercise reported a significant improvement in mental health compared to the control group. Specifically, they reported lower levels of anxiety and depression, improved mood, and increased self-esteem.

Conclusion : Regular exercise can have a positive impact on mental health and may be an effective intervention for individuals experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Applications of Research Findings

Research findings can be applied in various fields to improve processes, products, services, and outcomes. Here are some examples:

- Healthcare : Research findings in medicine and healthcare can be applied to improve patient outcomes, reduce morbidity and mortality rates, and develop new treatments for various diseases.

- Education : Research findings in education can be used to develop effective teaching methods, improve learning outcomes, and design new educational programs.

- Technology : Research findings in technology can be applied to develop new products, improve existing products, and enhance user experiences.

- Business : Research findings in business can be applied to develop new strategies, improve operations, and increase profitability.

- Public Policy: Research findings can be used to inform public policy decisions on issues such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development.

- Social Sciences: Research findings in social sciences can be used to improve understanding of human behavior and social phenomena, inform public policy decisions, and develop interventions to address social issues.

- Agriculture: Research findings in agriculture can be applied to improve crop yields, develop new farming techniques, and enhance food security.

- Sports : Research findings in sports can be applied to improve athlete performance, reduce injuries, and develop new training programs.

When to use Research Findings

Research findings can be used in a variety of situations, depending on the context and the purpose. Here are some examples of when research findings may be useful:

- Decision-making : Research findings can be used to inform decisions in various fields, such as business, education, healthcare, and public policy. For example, a business may use market research findings to make decisions about new product development or marketing strategies.

- Problem-solving : Research findings can be used to solve problems or challenges in various fields, such as healthcare, engineering, and social sciences. For example, medical researchers may use findings from clinical trials to develop new treatments for diseases.

- Policy development : Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies in various fields, such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development. For example, policymakers may use research findings to develop policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- Program evaluation: Research findings can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions in various fields, such as education, healthcare, and social services. For example, educational researchers may use findings from evaluations of educational programs to improve teaching and learning outcomes.

- Innovation: Research findings can be used to inspire or guide innovation in various fields, such as technology and engineering. For example, engineers may use research findings on materials science to develop new and innovative products.

Purpose of Research Findings

The purpose of research findings is to contribute to the knowledge and understanding of a particular topic or issue. Research findings are the result of a systematic and rigorous investigation of a research question or hypothesis, using appropriate research methods and techniques.

The main purposes of research findings are:

- To generate new knowledge : Research findings contribute to the body of knowledge on a particular topic, by adding new information, insights, and understanding to the existing knowledge base.

- To test hypotheses or theories : Research findings can be used to test hypotheses or theories that have been proposed in a particular field or discipline. This helps to determine the validity and reliability of the hypotheses or theories, and to refine or develop new ones.

- To inform practice: Research findings can be used to inform practice in various fields, such as healthcare, education, and business. By identifying best practices and evidence-based interventions, research findings can help practitioners to make informed decisions and improve outcomes.

- To identify gaps in knowledge: Research findings can help to identify gaps in knowledge and understanding of a particular topic, which can then be addressed by further research.

- To contribute to policy development: Research findings can be used to inform policy development in various fields, such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development. By providing evidence-based recommendations, research findings can help policymakers to develop effective policies that address societal challenges.

Characteristics of Research Findings

Research findings have several key characteristics that distinguish them from other types of information or knowledge. Here are some of the main characteristics of research findings:

- Objective : Research findings are based on a systematic and rigorous investigation of a research question or hypothesis, using appropriate research methods and techniques. As such, they are generally considered to be more objective and reliable than other types of information.

- Empirical : Research findings are based on empirical evidence, which means that they are derived from observations or measurements of the real world. This gives them a high degree of credibility and validity.

- Generalizable : Research findings are often intended to be generalizable to a larger population or context beyond the specific study. This means that the findings can be applied to other situations or populations with similar characteristics.

- Transparent : Research findings are typically reported in a transparent manner, with a clear description of the research methods and data analysis techniques used. This allows others to assess the credibility and reliability of the findings.

- Peer-reviewed: Research findings are often subject to a rigorous peer-review process, in which experts in the field review the research methods, data analysis, and conclusions of the study. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Reproducible : Research findings are often designed to be reproducible, meaning that other researchers can replicate the study using the same methods and obtain similar results. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

Advantages of Research Findings

Research findings have many advantages, which make them valuable sources of knowledge and information. Here are some of the main advantages of research findings:

- Evidence-based: Research findings are based on empirical evidence, which means that they are grounded in data and observations from the real world. This makes them a reliable and credible source of information.

- Inform decision-making: Research findings can be used to inform decision-making in various fields, such as healthcare, education, and business. By identifying best practices and evidence-based interventions, research findings can help practitioners and policymakers to make informed decisions and improve outcomes.

- Identify gaps in knowledge: Research findings can help to identify gaps in knowledge and understanding of a particular topic, which can then be addressed by further research. This contributes to the ongoing development of knowledge in various fields.

- Improve outcomes : Research findings can be used to develop and implement evidence-based practices and interventions, which have been shown to improve outcomes in various fields, such as healthcare, education, and social services.

- Foster innovation: Research findings can inspire or guide innovation in various fields, such as technology and engineering. By providing new information and understanding of a particular topic, research findings can stimulate new ideas and approaches to problem-solving.

- Enhance credibility: Research findings are generally considered to be more credible and reliable than other types of information, as they are based on rigorous research methods and are subject to peer-review processes.

Limitations of Research Findings

While research findings have many advantages, they also have some limitations. Here are some of the main limitations of research findings:

- Limited scope: Research findings are typically based on a particular study or set of studies, which may have a limited scope or focus. This means that they may not be applicable to other contexts or populations.

- Potential for bias : Research findings can be influenced by various sources of bias, such as researcher bias, selection bias, or measurement bias. This can affect the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Ethical considerations: Research findings can raise ethical considerations, particularly in studies involving human subjects. Researchers must ensure that their studies are conducted in an ethical and responsible manner, with appropriate measures to protect the welfare and privacy of participants.

- Time and resource constraints : Research studies can be time-consuming and require significant resources, which can limit the number and scope of studies that are conducted. This can lead to gaps in knowledge or a lack of research on certain topics.

- Complexity: Some research findings can be complex and difficult to interpret, particularly in fields such as science or medicine. This can make it challenging for practitioners and policymakers to apply the findings to their work.

- Lack of generalizability : While research findings are intended to be generalizable to larger populations or contexts, there may be factors that limit their generalizability. For example, cultural or environmental factors may influence how a particular intervention or treatment works in different populations or contexts.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

Research Topics – Ideas and Examples

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

Appendix in Research Paper – Examples and...

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and...

Data Verification – Process, Types and Examples

From Data to Discovery: The Findings Section of a Research Paper

Discover the role of the findings section of a research paper here. Explore strategies and techniques to maximize your understanding.

Are you curious about the Findings section of a research paper? Did you know that this is a part where all the juicy results and discoveries are laid out for the world to see? Undoubtedly, the findings section of a research paper plays a critical role in presenting and interpreting the collected data. It serves as a comprehensive account of the study’s results and their implications.

Well, look no further because we’ve got you covered! In this article, we’re diving into the ins and outs of presenting and interpreting data in the findings section. We’ll be sharing tips and tricks on how to effectively present your findings, whether it’s through tables, graphs, or good old descriptive statistics.

Overview of the Findings Section of a Research Paper

The findings section of a research paper presents the results and outcomes of the study or investigation. It is a crucial part of the research paper where researchers interpret and analyze the data collected and draw conclusions based on their findings. This section aims to answer the research questions or hypotheses formulated earlier in the paper and provide evidence to support or refute them.

In the findings section, researchers typically present the data clearly and organized. They may use tables, graphs, charts, or other visual aids to illustrate the patterns, trends, or relationships observed in the data. The findings should be presented objectively, without any bias or personal opinions, and should be accompanied by appropriate statistical analyses or methods to ensure the validity and reliability of the results.

Organizing the Findings Section

The findings section of the research paper organizes and presents the results obtained from the study in a clear and logical manner. Here is a suggested structure for organizing the Findings section:

Introduction to the Findings

Start the section by providing a brief overview of the research objectives and the methodology employed. Recapitulate the research questions or hypotheses addressed in the study.

To learn more about methodology, read this article .

Descriptive Statistics and Data Presentation

Present the collected data using appropriate descriptive statistics. This may involve using tables, graphs, charts, or other visual representations to convey the information effectively. Remember: we can easily help you with that.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Perform a thorough analysis of the data collected and describe the key findings. Present the results of statistical analyses or any other relevant methods used to analyze the data.

Discussion of Findings

Analyze and interpret the findings in the context of existing literature or theoretical frameworks . Discuss any patterns, trends, or relationships observed in the data. Compare and contrast the results with prior studies, highlighting similarities and differences.

Limitations and Constraints

Acknowledge and discuss any limitations or constraints that may have influenced the findings. This could include issues such as sample size, data collection methods, or potential biases.

Summarize the main findings of the study and emphasize their significance. Revisit the research questions or hypotheses and discuss whether they have been supported or refuted by the findings.

Presenting Data in the Findings Section

There are several ways to present data in the findings section of a research paper. Here are some common methods:

- Tables : Tables are commonly used to present organized and structured data. They are particularly useful when presenting numerical data with multiple variables or categories. Tables allow readers to easily compare and interpret the information presented. Learn how to cite tables in research papers here .

- Graphs and Charts: Graphs and charts are effective visual tools for presenting data, especially when illustrating trends, patterns, or relationships. Common types include bar graphs, line graphs, scatter plots, pie charts, and histograms. Graphs and charts provide a visual representation of the data, making it easier for readers to comprehend and interpret.

- Figures and Images: Figures and images can be used to present data that requires visual representation, such as maps, diagrams, or experimental setups. They can enhance the understanding of complex data or provide visual evidence to support the research findings.

- Descriptive Statistics: Descriptive statistics provide summary measures of central tendency (e.g., mean, median, mode) and dispersion (e.g., standard deviation, range) for numerical data. These statistics can be included in the text or presented in tables or graphs to provide a concise summary of the data distribution.

How to Effectively Interpret Results

Interpreting the results is a crucial aspect of the findings section in a research paper. It involves analyzing the data collected and drawing meaningful conclusions based on the findings. Following are the guidelines on how to effectively interpret the results.

Step 1 – Begin with a Recap

Start by restating the research questions or hypotheses to provide context for the interpretation. Remind readers of the specific objectives of the study to help them understand the relevance of the findings.

Step 2 – Relate Findings to Research Questions

Clearly articulate how the results address the research questions or hypotheses. Discuss each finding in relation to the original objectives and explain how it contributes to answering the research questions or supporting/refuting the hypotheses.

Step 3 – Compare with Existing Literature

Compare and contrast the findings with previous studies or existing literature. Highlight similarities, differences, or discrepancies between your results and those of other researchers. Discuss any consistencies or contradictions and provide possible explanations for the observed variations.

Step 4 – Consider Limitations and Alternative Explanations

Acknowledge the limitations of the study and discuss how they may have influenced the results. Explore alternative explanations or factors that could potentially account for the findings. Evaluate the robustness of the results in light of the limitations and alternative interpretations.

Step 5 – Discuss Implications and Significance

Highlight any potential applications or areas where further research is needed based on the outcomes of the study.

Step 6 – Address Inconsistencies and Contradictions

If there are any inconsistencies or contradictions in the findings, address them directly. Discuss possible reasons for the discrepancies and consider their implications for the overall interpretation. Be transparent about any uncertainties or unresolved issues.

Step 7 – Be Objective and Data-Driven

Present the interpretation objectively, based on the evidence and data collected. Avoid personal biases or subjective opinions. Use logical reasoning and sound arguments to support your interpretations.

Reporting Statistical Significance

When reporting statistical significance in the findings section of a research paper, it is important to accurately convey the results of statistical analyses and their implications. Here are some guidelines on how to report statistical significance effectively:

- Clearly State the Statistical Test: Begin by clearly stating the specific statistical test or analysis used to determine statistical significance. For example, you might mention that a t-test, chi-square test, ANOVA, correlation analysis, or regression analysis was employed.

- Report the Test Statistic: Provide the value of the test statistic obtained from the analysis. This could be the t-value, F-value, chi-square value, correlation coefficient, or any other relevant statistic depending on the test used.

- State the Degrees of Freedom: Indicate the degrees of freedom associated with the statistical test. Degrees of freedom represent the number of independent pieces of information available for estimating a statistic. For example, in a t-test, degrees of freedom would be mentioned as (df = n1 + n2 – 2) for an independent samples test or (df = N – 2) for a paired samples test.

- Report the p-value: The p-value indicates the probability of obtaining results as extreme or more extreme than the observed results, assuming the null hypothesis is true. Report the p-value associated with the statistical test. For example, p < 0.05 denotes statistical significance at the conventional level of α = 0.05.

- Provide the Conclusion: Based on the p-value obtained, state whether the results are statistically significant or not. If the p-value is less than the predetermined threshold (e.g., p < 0.05), state that the results are statistically significant. If the p-value is greater than the threshold, state that the results are not statistically significant.

- Discuss the Interpretation: After reporting statistical significance, discuss the practical or theoretical implications of the finding. Explain what the significant result means in the context of your research questions or hypotheses. Address the effect size and practical significance of the findings, if applicable.

- Consider Effect Size Measures: Along with statistical significance, it is often important to report effect size measures. Effect size quantifies the magnitude of the relationship or difference observed in the data. Common effect size measures include Cohen’s d, eta-squared, or Pearson’s r. Reporting effect size provides additional meaningful information about the strength of the observed effects.

- Be Accurate and Transparent: Ensure that the reported statistical significance and associated values are accurate. Avoid misinterpreting or misrepresenting the results. Be transparent about the statistical tests conducted, any assumptions made, and potential limitations or caveats that may impact the interpretation of the significant results.

Conclusion of the Findings Section

The conclusion of the findings section in a research paper serves as a summary and synthesis of the key findings and their implications. It is an opportunity to tie together the results, discuss their significance, and address the research objectives. Here are some guidelines on how to write the conclusion of the Findings section:

Summarize the Key Findings

Begin by summarizing the main findings of the study. Provide a concise overview of the significant results, patterns, or relationships that emerged from the data analysis. Highlight the most important findings that directly address the research questions or hypotheses.

Revisit the Research Objectives

Remind the reader of the research objectives stated at the beginning of the paper. Discuss how the findings contribute to achieving those objectives and whether they support or challenge the initial research questions or hypotheses.

Suggest Future Directions

Identify areas for further research or future directions based on the findings. Discuss any unanswered questions, unresolved issues, or new avenues of inquiry that emerged during the study. Propose potential research opportunities that can build upon the current findings.

The Best Scientific Figures to Represent Your Findings

Have you heard of any tool that helps you represent your findings through visuals like graphs, pie charts, and infographics? Well, if you haven’t, then here’s the tool you need to explore – Mind the Graph . It’s the tool that has the best scientific figures to represent your findings. Go, try it now, and make your research findings stand out!

Related Articles

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Sign Up for Free

Try the best infographic maker and promote your research with scientifically-accurate beautiful figures

no credit card required

About Sowjanya Pedada

Sowjanya is a passionate writer and an avid reader. She holds MBA in Agribusiness Management and now is working as a content writer. She loves to play with words and hopes to make a difference in the world through her writings. Apart from writing, she is interested in reading fiction novels and doing craftwork. She also loves to travel and explore different cuisines and spend time with her family and friends.

Content tags

How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For qualitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD). Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

So, you’ve collected and analysed your qualitative data, and it’s time to write up your results chapter. But where do you start? In this post, we’ll guide you through the qualitative results chapter (also called the findings chapter), step by step.

Overview: Qualitative Results Chapter

- What (exactly) the qualitative results chapter is

- What to include in your results chapter

- How to write up your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

- Free results chapter template

What exactly is the results chapter?

The results chapter in a dissertation or thesis (or any formal academic research piece) is where you objectively and neutrally present the findings of your qualitative analysis (or analyses if you used multiple qualitative analysis methods ). This chapter can sometimes be combined with the discussion chapter (where you interpret the data and discuss its meaning), depending on your university’s preference. We’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as that’s the most common approach.

In contrast to a quantitative results chapter that presents numbers and statistics, a qualitative results chapter presents data primarily in the form of words . But this doesn’t mean that a qualitative study can’t have quantitative elements – you could, for example, present the number of times a theme or topic pops up in your data, depending on the analysis method(s) you adopt.

Adding a quantitative element to your study can add some rigour, which strengthens your results by providing more evidence for your claims. This is particularly common when using qualitative content analysis. Keep in mind though that qualitative research aims to achieve depth, richness and identify nuances , so don’t get tunnel vision by focusing on the numbers. They’re just cream on top in a qualitative analysis.

So, to recap, the results chapter is where you objectively present the findings of your analysis, without interpreting them (you’ll save that for the discussion chapter). With that out the way, let’s take a look at what you should include in your results chapter.

What should you include in the results chapter?

As we’ve mentioned, your qualitative results chapter should purely present and describe your results , not interpret them in relation to the existing literature or your research questions . Any speculations or discussion about the implications of your findings should be reserved for your discussion chapter.

In your results chapter, you’ll want to talk about your analysis findings and whether or not they support your hypotheses (if you have any). Naturally, the exact contents of your results chapter will depend on which qualitative analysis method (or methods) you use. For example, if you were to use thematic analysis, you’d detail the themes identified in your analysis, using extracts from the transcripts or text to support your claims.

While you do need to present your analysis findings in some detail, you should avoid dumping large amounts of raw data in this chapter. Instead, focus on presenting the key findings and using a handful of select quotes or text extracts to support each finding . The reams of data and analysis can be relegated to your appendices.

While it’s tempting to include every last detail you found in your qualitative analysis, it is important to make sure that you report only that which is relevant to your research aims, objectives and research questions . Always keep these three components, as well as your hypotheses (if you have any) front of mind when writing the chapter and use them as a filter to decide what’s relevant and what’s not.

Need a helping hand?

How do I write the results chapter?

Now that we’ve covered the basics, it’s time to look at how to structure your chapter. Broadly speaking, the results chapter needs to contain three core components – the introduction, the body and the concluding summary. Let’s take a look at each of these.

Section 1: Introduction

The first step is to craft a brief introduction to the chapter. This intro is vital as it provides some context for your findings. In your introduction, you should begin by reiterating your problem statement and research questions and highlight the purpose of your research . Make sure that you spell this out for the reader so that the rest of your chapter is well contextualised.

The next step is to briefly outline the structure of your results chapter. In other words, explain what’s included in the chapter and what the reader can expect. In the results chapter, you want to tell a story that is coherent, flows logically, and is easy to follow , so make sure that you plan your structure out well and convey that structure (at a high level), so that your reader is well oriented.

The introduction section shouldn’t be lengthy. Two or three short paragraphs should be more than adequate. It is merely an introduction and overview, not a summary of the chapter.

Pro Tip – To help you structure your chapter, it can be useful to set up an initial draft with (sub)section headings so that you’re able to easily (re)arrange parts of your chapter. This will also help your reader to follow your results and give your chapter some coherence. Be sure to use level-based heading styles (e.g. Heading 1, 2, 3 styles) to help the reader differentiate between levels visually. You can find these options in Word (example below).

Section 2: Body

Before we get started on what to include in the body of your chapter, it’s vital to remember that a results section should be completely objective and descriptive, not interpretive . So, be careful not to use words such as, “suggests” or “implies”, as these usually accompany some form of interpretation – that’s reserved for your discussion chapter.

The structure of your body section is very important , so make sure that you plan it out well. When planning out your qualitative results chapter, create sections and subsections so that you can maintain the flow of the story you’re trying to tell. Be sure to systematically and consistently describe each portion of results. Try to adopt a standardised structure for each portion so that you achieve a high level of consistency throughout the chapter.

For qualitative studies, results chapters tend to be structured according to themes , which makes it easier for readers to follow. However, keep in mind that not all results chapters have to be structured in this manner. For example, if you’re conducting a longitudinal study, you may want to structure your chapter chronologically. Similarly, you might structure this chapter based on your theoretical framework . The exact structure of your chapter will depend on the nature of your study , especially your research questions.

As you work through the body of your chapter, make sure that you use quotes to substantiate every one of your claims . You can present these quotes in italics to differentiate them from your own words. A general rule of thumb is to use at least two pieces of evidence per claim, and these should be linked directly to your data. Also, remember that you need to include all relevant results , not just the ones that support your assumptions or initial leanings.

In addition to including quotes, you can also link your claims to the data by using appendices , which you should reference throughout your text. When you reference, make sure that you include both the name/number of the appendix , as well as the line(s) from which you drew your data.

As referencing styles can vary greatly, be sure to look up the appendix referencing conventions of your university’s prescribed style (e.g. APA , Harvard, etc) and keep this consistent throughout your chapter.

Section 3: Concluding summary

The concluding summary is very important because it summarises your key findings and lays the foundation for the discussion chapter . Keep in mind that some readers may skip directly to this section (from the introduction section), so make sure that it can be read and understood well in isolation.

In this section, you need to remind the reader of the key findings. That is, the results that directly relate to your research questions and that you will build upon in your discussion chapter. Remember, your reader has digested a lot of information in this chapter, so you need to use this section to remind them of the most important takeaways.

Importantly, the concluding summary should not present any new information and should only describe what you’ve already presented in your chapter. Keep it concise – you’re not summarising the whole chapter, just the essentials.

Tips for writing an A-grade results chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear picture of what the qualitative results chapter is all about, here are some quick tips and reminders to help you craft a high-quality chapter:

- Your results chapter should be written in the past tense . You’ve done the work already, so you want to tell the reader what you found , not what you are currently finding .

- Make sure that you review your work multiple times and check that every claim is adequately backed up by evidence . Aim for at least two examples per claim, and make use of an appendix to reference these.

- When writing up your results, make sure that you stick to only what is relevant . Don’t waste time on data that are not relevant to your research objectives and research questions.

- Use headings and subheadings to create an intuitive, easy to follow piece of writing. Make use of Microsoft Word’s “heading styles” and be sure to use them consistently.

- When referring to numerical data, tables and figures can provide a useful visual aid. When using these, make sure that they can be read and understood independent of your body text (i.e. that they can stand-alone). To this end, use clear, concise labels for each of your tables or figures and make use of colours to code indicate differences or hierarchy.

- Similarly, when you’re writing up your chapter, it can be useful to highlight topics and themes in different colours . This can help you to differentiate between your data if you get a bit overwhelmed and will also help you to ensure that your results flow logically and coherently.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your results chapter (or any chapter of your dissertation or thesis), check out our private dissertation coaching service here or book a free initial consultation to discuss how we can help you.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

22 Comments

This was extremely helpful. Thanks a lot guys

Hi, thanks for the great research support platform created by the gradcoach team!

I wanted to ask- While “suggests” or “implies” are interpretive terms, what terms could we use for the results chapter? Could you share some examples of descriptive terms?

I think that instead of saying, ‘The data suggested, or The data implied,’ you can say, ‘The Data showed or revealed, or illustrated or outlined’…If interview data, you may say Jane Doe illuminated or elaborated, or Jane Doe described… or Jane Doe expressed or stated.

I found this article very useful. Thank you very much for the outstanding work you are doing.

What if i have 3 different interviewees answering the same interview questions? Should i then present the results in form of the table with the division on the 3 perspectives or rather give a results in form of the text and highlight who said what?

I think this tabular representation of results is a great idea. I am doing it too along with the text. Thanks

That was helpful was struggling to separate the discussion from the findings

this was very useful, Thank you.

Very helpful, I am confident to write my results chapter now.

It is so helpful! It is a good job. Thank you very much!

Very useful, well explained. Many thanks.

Hello, I appreciate the way you provided a supportive comments about qualitative results presenting tips

I loved this! It explains everything needed, and it has helped me better organize my thoughts. What words should I not use while writing my results section, other than subjective ones.

Thanks a lot, it is really helpful

Thank you so much dear, i really appropriate your nice explanations about this.

Thank you so much for this! I was wondering if anyone could help with how to prproperly integrate quotations (Excerpts) from interviews in the finding chapter in a qualitative research. Please GradCoach, address this issue and provide examples.

what if I’m not doing any interviews myself and all the information is coming from case studies that have already done the research.

Very helpful thank you.

This was very helpful as I was wondering how to structure this part of my dissertation, to include the quotes… Thanks for this explanation

This is very helpful, thanks! I am required to write up my results chapters with the discussion in each of them – any tips and tricks for this strategy?

For qualitative studies, can the findings be structured according to the Research questions? Thank you.

Do I need to include literature/references in my findings chapter?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Surveys Academic Research

Research Summary: What is it & how to write one

The Research Summary is used to report facts about a study clearly. You will almost certainly be required to prepare a research summary during your academic research or while on a research project for your organization.

If it is the first time you have to write one, the writing requirements may confuse you. The instructors generally assign someone to write a summary of the research work. Research summaries require the writer to have a thorough understanding of the issue.

This article will discuss the definition of a research summary and how to write one.

What is a research summary?

A research summary is a piece of writing that summarizes your research on a specific topic. Its primary goal is to offer the reader a detailed overview of the study with the key findings. A research summary generally contains the article’s structure in which it is written.

You must know the goal of your analysis before you launch a project. A research overview summarizes the detailed response and highlights particular issues raised in it. Writing it might be somewhat troublesome. To write a good overview, you want to start with a structure in mind. Read on for our guide.

Why is an analysis recap so important?

Your summary or analysis is going to tell readers everything about your research project. This is the critical piece that your stakeholders will read to identify your findings and valuable insights. Having a good and concise research summary that presents facts and comes with no research biases is the critical deliverable of any research project.

We’ve put together a cheat sheet to help you write a good research summary below.

Research Summary Guide

- Why was this research done? – You want to give a clear description of why this research study was done. What hypothesis was being tested?

- Who was surveyed? – The what and why or your research decides who you’re going to interview/survey. Your research summary has a detailed note on who participated in the study and why they were selected.

- What was the methodology? – Talk about the methodology. Did you do face-to-face interviews? Was it a short or long survey or a focus group setting? Your research methodology is key to the results you’re going to get.

- What were the key findings? – This can be the most critical part of the process. What did we find out after testing the hypothesis? This section, like all others, should be just facts, facts facts. You’re not sharing how you feel about the findings. Keep it bias-free.

- Conclusion – What are the conclusions that were drawn from the findings. A good example of a conclusion. Surprisingly, most people interviewed did not watch the lunar eclipse in 2022, which is unexpected given that 100% of those interviewed knew about it before it happened.

- Takeaways and action points – This is where you bring in your suggestion. Given the data you now have from the research, what are the takeaways and action points? If you’re a researcher running this research project for your company, you’ll use this part to shed light on your recommended action plans for the business.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

If you’re doing any research, you will write a summary, which will be the most viewed and more important part of the project. So keep a guideline in mind before you start. Focus on the content first and then worry about the length. Use the cheat sheet/checklist in this article to organize your summary, and that’s all you need to write a great research summary!

But once your summary is ready, where is it stored? Most teams have multiple documents in their google drives, and it’s a nightmare to find projects that were done in the past. Your research data should be democratized and easy to use.

We at QuestionPro launched a research repository for research teams, and our clients love it. All your data is in one place, and everything is searchable, including your research summaries!

Authors: Prachi, Anas

MORE LIKE THIS

Closed-Loop Management: The Key to Customer Centricity

Sep 3, 2024

Net Trust Score: Tool for Measuring Trust in Organization

Sep 2, 2024

Why You Should Attend XDAY 2024

Aug 30, 2024

Alchemer vs Qualtrics: Find out which one you should choose

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Results/Findings Section in Research

What is the research paper Results section and what does it do?

The Results section of a scientific research paper represents the core findings of a study derived from the methods applied to gather and analyze information. It presents these findings in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation from the author, setting up the reader for later interpretation and evaluation in the Discussion section. A major purpose of the Results section is to break down the data into sentences that show its significance to the research question(s).

The Results section appears third in the section sequence in most scientific papers. It follows the presentation of the Methods and Materials and is presented before the Discussion section —although the Results and Discussion are presented together in many journals. This section answers the basic question “What did you find in your research?”

What is included in the Results section?

The Results section should include the findings of your study and ONLY the findings of your study. The findings include:

- Data presented in tables, charts, graphs, and other figures (may be placed into the text or on separate pages at the end of the manuscript)

- A contextual analysis of this data explaining its meaning in sentence form

- All data that corresponds to the central research question(s)

- All secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

If the scope of the study is broad, or if you studied a variety of variables, or if the methodology used yields a wide range of different results, the author should present only those results that are most relevant to the research question stated in the Introduction section .

As a general rule, any information that does not present the direct findings or outcome of the study should be left out of this section. Unless the journal requests that authors combine the Results and Discussion sections, explanations and interpretations should be omitted from the Results.

How are the results organized?

The best way to organize your Results section is “logically.” One logical and clear method of organizing research results is to provide them alongside the research questions—within each research question, present the type of data that addresses that research question.

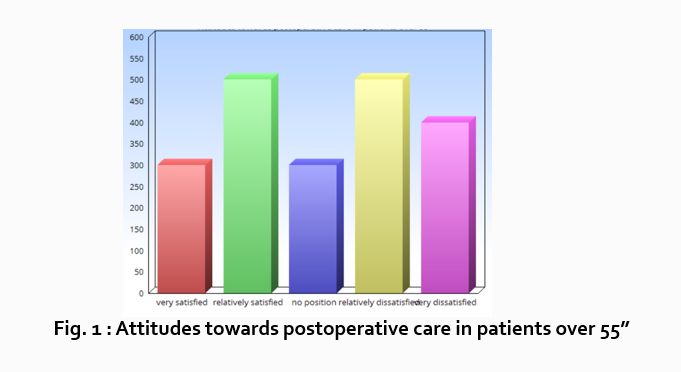

Let’s look at an example. Your research question is based on a survey among patients who were treated at a hospital and received postoperative care. Let’s say your first research question is:

“What do hospital patients over age 55 think about postoperative care?”

This can actually be represented as a heading within your Results section, though it might be presented as a statement rather than a question:

Attitudes towards postoperative care in patients over the age of 55

Now present the results that address this specific research question first. In this case, perhaps a table illustrating data from a survey. Likert items can be included in this example. Tables can also present standard deviations, probabilities, correlation matrices, etc.

Following this, present a content analysis, in words, of one end of the spectrum of the survey or data table. In our example case, start with the POSITIVE survey responses regarding postoperative care, using descriptive phrases. For example:

“Sixty-five percent of patients over 55 responded positively to the question “ Are you satisfied with your hospital’s postoperative care ?” (Fig. 2)

Include other results such as subcategory analyses. The amount of textual description used will depend on how much interpretation of tables and figures is necessary and how many examples the reader needs in order to understand the significance of your research findings.

Next, present a content analysis of another part of the spectrum of the same research question, perhaps the NEGATIVE or NEUTRAL responses to the survey. For instance:

“As Figure 1 shows, 15 out of 60 patients in Group A responded negatively to Question 2.”

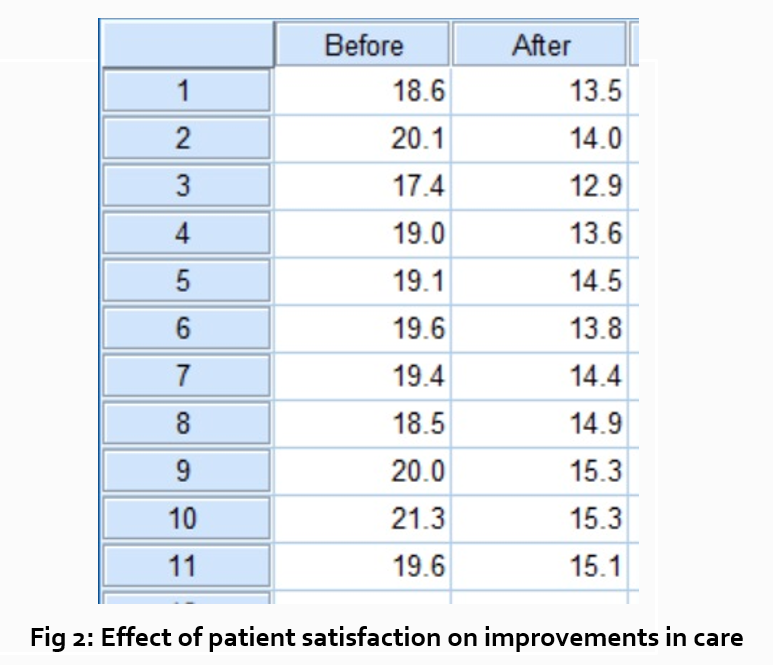

After you have assessed the data in one figure and explained it sufficiently, move on to your next research question. For example:

“How does patient satisfaction correspond to in-hospital improvements made to postoperative care?”

This kind of data may be presented through a figure or set of figures (for instance, a paired T-test table).

Explain the data you present, here in a table, with a concise content analysis:

“The p-value for the comparison between the before and after groups of patients was .03% (Fig. 2), indicating that the greater the dissatisfaction among patients, the more frequent the improvements that were made to postoperative care.”

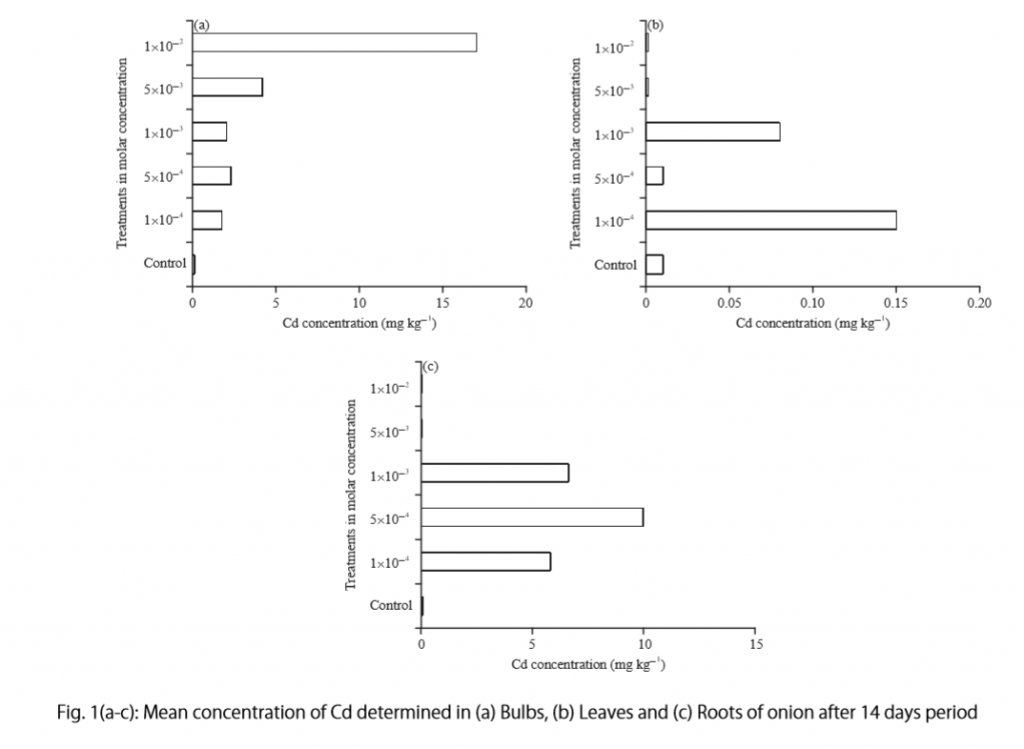

Let’s examine another example of a Results section from a study on plant tolerance to heavy metal stress . In the Introduction section, the aims of the study are presented as “determining the physiological and morphological responses of Allium cepa L. towards increased cadmium toxicity” and “evaluating its potential to accumulate the metal and its associated environmental consequences.” The Results section presents data showing how these aims are achieved in tables alongside a content analysis, beginning with an overview of the findings:

“Cadmium caused inhibition of root and leave elongation, with increasing effects at higher exposure doses (Fig. 1a-c).”

The figure containing this data is cited in parentheses. Note that this author has combined three graphs into one single figure. Separating the data into separate graphs focusing on specific aspects makes it easier for the reader to assess the findings, and consolidating this information into one figure saves space and makes it easy to locate the most relevant results.

Following this overall summary, the relevant data in the tables is broken down into greater detail in text form in the Results section.

- “Results on the bio-accumulation of cadmium were found to be the highest (17.5 mg kgG1) in the bulb, when the concentration of cadmium in the solution was 1×10G2 M and lowest (0.11 mg kgG1) in the leaves when the concentration was 1×10G3 M.”

Captioning and Referencing Tables and Figures

Tables and figures are central components of your Results section and you need to carefully think about the most effective way to use graphs and tables to present your findings . Therefore, it is crucial to know how to write strong figure captions and to refer to them within the text of the Results section.

The most important advice one can give here as well as throughout the paper is to check the requirements and standards of the journal to which you are submitting your work. Every journal has its own design and layout standards, which you can find in the author instructions on the target journal’s website. Perusing a journal’s published articles will also give you an idea of the proper number, size, and complexity of your figures.

Regardless of which format you use, the figures should be placed in the order they are referenced in the Results section and be as clear and easy to understand as possible. If there are multiple variables being considered (within one or more research questions), it can be a good idea to split these up into separate figures. Subsequently, these can be referenced and analyzed under separate headings and paragraphs in the text.

To create a caption, consider the research question being asked and change it into a phrase. For instance, if one question is “Which color did participants choose?”, the caption might be “Color choice by participant group.” Or in our last research paper example, where the question was “What is the concentration of cadmium in different parts of the onion after 14 days?” the caption reads:

“Fig. 1(a-c): Mean concentration of Cd determined in (a) bulbs, (b) leaves, and (c) roots of onions after a 14-day period.”

Steps for Composing the Results Section

Because each study is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to designing a strategy for structuring and writing the section of a research paper where findings are presented. The content and layout of this section will be determined by the specific area of research, the design of the study and its particular methodologies, and the guidelines of the target journal and its editors. However, the following steps can be used to compose the results of most scientific research studies and are essential for researchers who are new to preparing a manuscript for publication or who need a reminder of how to construct the Results section.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the target journal or publisher provides authors and read research papers it has published, especially those with similar topics, methods, or results to your study.

- The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches.

- Note length limitations on restrictions on content. For instance, while many journals require the Results and Discussion sections to be separate, others do not—qualitative research papers often include results and interpretations in the same section (“Results and Discussion”).

- Reading the aims and scope in the journal’s “ guide for authors ” section and understanding the interests of its readers will be invaluable in preparing to write the Results section.

Step 2 : Consider your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements and catalogue your results.

- Focus on experimental results and other findings that are especially relevant to your research questions and objectives and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses.

- Catalogue your findings—use subheadings to streamline and clarify your report. This will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Create appendices that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers.

- Decide how you will structure of your results. You might match the order of the research questions and hypotheses to your results, or you could arrange them according to the order presented in the Methods section. A chronological order or even a hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. Consider your audience, evidence, and most importantly, the objectives of your research when choosing a structure for presenting your findings.

Step 3 : Design figures and tables to present and illustrate your data.

- Tables and figures should be numbered according to the order in which they are mentioned in the main text of the paper.

- Information in figures should be relatively self-explanatory (with the aid of captions), and their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for readers to understand the findings without reading all of the text.

- Use tables and figures as a focal point to tell a clear and informative story about your research and avoid repeating information. But remember that while figures clarify and enhance the text, they cannot replace it.

Step 4 : Draft your Results section using the findings and figures you have organized.

- The goal is to communicate this complex information as clearly and precisely as possible; precise and compact phrases and sentences are most effective.

- In the opening paragraph of this section, restate your research questions or aims to focus the reader’s attention to what the results are trying to show. It is also a good idea to summarize key findings at the end of this section to create a logical transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows.

- Try to write in the past tense and the active voice to relay the findings since the research has already been done and the agent is usually clear. This will ensure that your explanations are also clear and logical.

- Make sure that any specialized terminology or abbreviation you have used here has been defined and clarified in the Introduction section .

Step 5 : Review your draft; edit and revise until it reports results exactly as you would like to have them reported to your readers.

- Double-check the accuracy and consistency of all the data, as well as all of the visual elements included.

- Read your draft aloud to catch language errors (grammar, spelling, and mechanics), awkward phrases, and missing transitions.

- Ensure that your results are presented in the best order to focus on objectives and prepare readers for interpretations, valuations, and recommendations in the Discussion section . Look back over the paper’s Introduction and background while anticipating the Discussion and Conclusion sections to ensure that the presentation of your results is consistent and effective.

- Consider seeking additional guidance on your paper. Find additional readers to look over your Results section and see if it can be improved in any way. Peers, professors, or qualified experts can provide valuable insights.

One excellent option is to use a professional English proofreading and editing service such as Wordvice, including our paper editing service . With hundreds of qualified editors from dozens of scientific fields, Wordvice has helped thousands of authors revise their manuscripts and get accepted into their target journals. Read more about the proofreading and editing process before proceeding with getting academic editing services and manuscript editing services for your manuscript.

As the representation of your study’s data output, the Results section presents the core information in your research paper. By writing with clarity and conciseness and by highlighting and explaining the crucial findings of their study, authors increase the impact and effectiveness of their research manuscripts.

For more articles and videos on writing your research manuscript, visit Wordvice’s Resources page.

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Chapter 15: interpreting results and drawing conclusions.

Holger J Schünemann, Gunn E Vist, Julian PT Higgins, Nancy Santesso, Jonathan J Deeks, Paul Glasziou, Elie A Akl, Gordon H Guyatt; on behalf of the Cochrane GRADEing Methods Group

Key Points:

- This chapter provides guidance on interpreting the results of synthesis in order to communicate the conclusions of the review effectively.

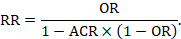

- Methods are presented for computing, presenting and interpreting relative and absolute effects for dichotomous outcome data, including the number needed to treat (NNT).

- For continuous outcome measures, review authors can present summary results for studies using natural units of measurement or as minimal important differences when all studies use the same scale. When studies measure the same construct but with different scales, review authors will need to find a way to interpret the standardized mean difference, or to use an alternative effect measure for the meta-analysis such as the ratio of means.

- Review authors should not describe results as ‘statistically significant’, ‘not statistically significant’ or ‘non-significant’ or unduly rely on thresholds for P values, but report the confidence interval together with the exact P value.

- Review authors should not make recommendations about healthcare decisions, but they can – after describing the certainty of evidence and the balance of benefits and harms – highlight different actions that might be consistent with particular patterns of values and preferences and other factors that determine a decision such as cost.

Cite this chapter as: Schünemann HJ, Vist GE, Higgins JPT, Santesso N, Deeks JJ, Glasziou P, Akl EA, Guyatt GH. Chapter 15: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions [last updated August 2023]. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. Cochrane, 2024. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

15.1 Introduction