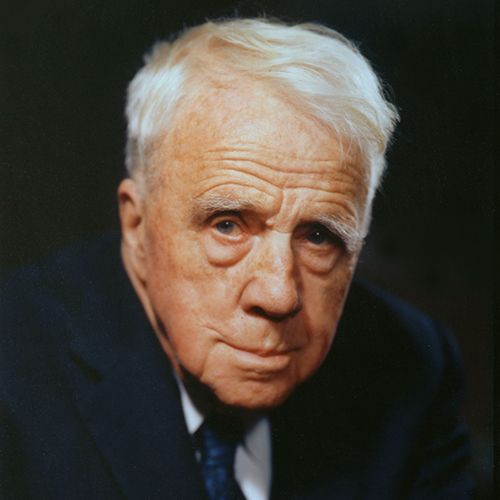

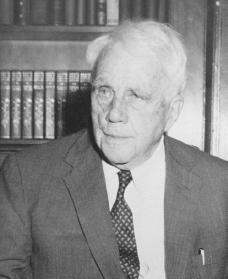

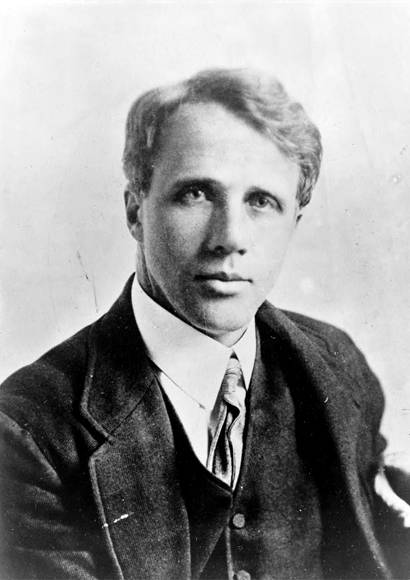

Robert Frost

(1874-1963)

Who Was Robert Frost?

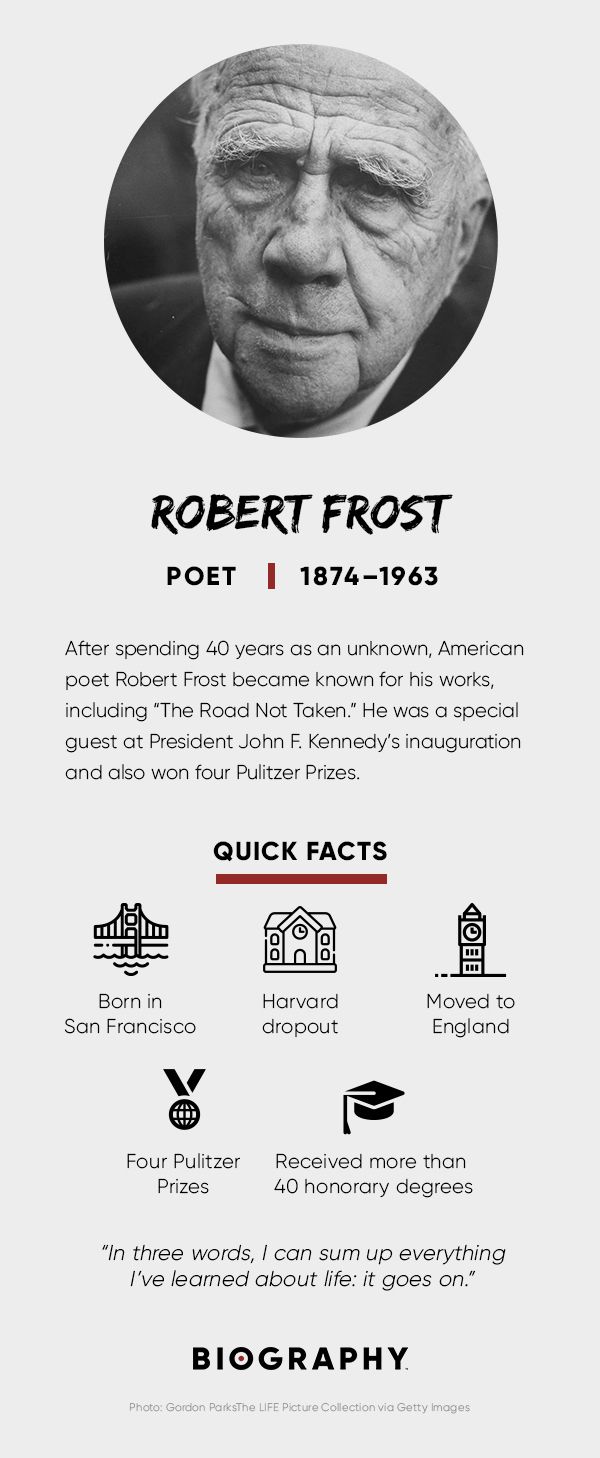

Robert Frost was an American poet and winner of four Pulitzer Prizes. Famous works include “Fire and Ice,” “Mending Wall,” “Birches,” “Out Out,” “Nothing Gold Can Stay” and “Home Burial.” His 1916 poem, "The Road Not Taken," is often read at graduation ceremonies across the United States. As a special guest at President John F. Kennedy ’s inauguration, Frost became a poetic force and the unofficial "poet laureate" of the United States.

Frost spent his first 40 years as an unknown. He exploded on the scene after returning from England at the beginning of World War I . He died of complications from prostate surgery on January 29, 1963.

Early Years

Frost was born on March 26, 1874, in San Francisco, California. He spent the first 11 years of his life there, until his journalist father, William Prescott Frost Jr., died of tuberculosis.

Following his father's passing, Frost moved with his mother and sister, Jeanie, to the town of Lawrence, Massachusetts. They moved in with his grandparents, and Frost attended Lawrence High School.

After high school, Frost attended Dartmouth College for several months, returning home to work a slew of unfulfilling jobs.

Beginning in 1897, Frost attended Harvard University but had to drop out after two years due to health concerns. He returned to Lawrence to join his wife.

In 1900, Frost moved with his wife and children to a farm in New Hampshire — property that Frost's grandfather had purchased for them—and they attempted to make a life on it for the next 12 years. Though it was a fruitful time for Frost's writing, it was a difficult period in his personal life and followed the deaths of two of his young children.

During that time, Frost and Elinor attempted several endeavors, including poultry farming, all of which were fairly unsuccessful.

Despite such challenges, it was during this time that Frost acclimated himself to rural life. In fact, he grew to depict it quite well, and began setting many of his poems in the countryside.

Frost met his future love and wife, Elinor White, when they were both attending Lawrence High School. She was his co-valedictorian when they graduated in 1892.

In 1894, Frost proposed to White, who was attending St. Lawrence University , but she turned him down because she first wanted to finish school. Frost then decided to leave on a trip to Virginia, and when he returned, he proposed again. By then, White had graduated from college, and she accepted. They married on December 19, 1895.

White died in 1938. Diagnosed with cancer in 1937 and having undergone surgery, she also had had a long history of heart trouble, to which she ultimately succumbed.

Frost and White had six children together. Their first child, Elliot, was born in 1896. Daughter Lesley was born in 1899.

Elliot died of cholera in 1900. After his death, Elinor gave birth to four more children: son Carol (1902), who would commit suicide in 1940; Irma (1903), who later developed mental illness; Marjorie (1905), who died in her late 20s after giving birth; and Elinor (1907), who died just weeks after she was born.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S ROBERT FROST FACT CARD

Early Poetry

In 1894, Frost had his first poem, "My Butterfly: an Elegy," published in The Independent , a weekly literary journal based in New York City .

Two poems, "The Tuft of Flowers" and "The Trial by Existence," were published in 1906. He could not find any publishers who were willing to underwrite his other poems.

In 1912, Frost and Elinor decided to sell the farm in New Hampshire and move the family to England, where they hoped there would be more publishers willing to take a chance on new poets.

Within just a few months, Frost, now 38, found a publisher who would print his first book of poems, A Boy’s Will , followed by North of Boston a year later.

It was at this time that Frost met fellow poets Ezra Pound and Edward Thomas, two men who would affect his life in significant ways. Pound and Thomas were the first to review his work in a favorable light, as well as provide significant encouragement. Frost credited Thomas's long walks over the English landscape as the inspiration for one of his most famous poems, "The Road Not Taken."

Apparently, Thomas's indecision and regret regarding what paths to take inspired Frost's work. The time Frost spent in England was one of the most significant periods in his life, but it was short-lived. Shortly after World War I broke out in August 1914, Frost and Elinor were forced to return to America.

Public Recognition for Frost’s Poetry

When Frost arrived back in America, his reputation had preceded him, and he was well-received by the literary world. His new publisher, Henry Holt, who would remain with him for the rest of his life, had purchased all of the copies of North of Boston . In 1916, he published Frost's Mountain Interval , a collection of other works that he created while in England, including a tribute to Thomas.

Journals such as the Atlantic Monthly , who had turned Frost down when he submitted work earlier, now came calling. Frost famously sent the Atlantic the same poems that they had rejected before his stay in England.

In 1915, Frost and Elinor settled down on a farm that they purchased in Franconia, New Hampshire. There, Frost began a long career as a teacher at several colleges, reciting poetry to eager crowds and writing all the while.

He taught at Dartmouth and the University of Michigan at various times, but his most significant association was with Amherst College , where he taught steadily during the period from 1916 until his wife’s death in 1938. The main library is now named in his honor.

For a period of more than 40 years beginning in 1921, Frost also spent almost every summer and fall at Middlebury College , teaching English on its campus in Ripton, Vermont.

In the late 1950s, Frost, along with Ernest Hemingway and T. S. Eliot , championed the release of his old acquaintance Ezra Pound, who was being held in a federal mental hospital for treason due to his involvement with fascists in Italy during World War II . Pound was released in 1958, after the indictments were dropped.

Famous Poems

Some of Frost’s most well-known poems include:

- “The Road Not Taken”

- “Fire and Ice”

- “Mending Wall”

- “Home Burial”

- “The Death of the Hired Man”

- “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening”

- “Acquainted with the Night”

- “Nothing Gold Can Stay”

Pulitzer Prizes and Awards

During his lifetime, Frost received more than 40 honorary degrees.

In 1924, Frost was awarded his first of four Pulitzer Prizes, for his book New Hampshire . He would subsequently win Pulitzers for Collected Poems (1931), A Further Range (1937) and A Witness Tree (1943).

In 1960, Congress awarded Frost the Congressional Gold Medal.

President John F. Kennedy’s Inauguration

At the age of 86, Frost was honored when asked to write and recite a poem for President John F. Kennedy's 1961 inauguration. His sight now failing, he was not able to see the words in the sunlight and substituted the reading of one of his poems, "The Gift Outright," which he had committed to memory.

Soviet Union Tour

In 1962, Frost visited the Soviet Union on a goodwill tour. However, when he accidentally misrepresented a statement made by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev following their meeting, he unwittingly undid much of the good intended by his visit.

On January 29, 1963, Frost died from complications related to prostate surgery. He was survived by two of his daughters, Lesley and Irma. His ashes are interred in a family plot in Bennington, Vermont.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Robert Lee Frost

- Birth Year: 1874

- Birth date: March 26, 1874

- Birth State: California

- Birth City: San Francisco

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Robert Frost was an American poet who depicted realistic New England life through language and situations familiar to the common man. He won four Pulitzer Prizes for his work and spoke at John F. Kennedy's 1961 inauguration.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Aries

- Harvard University

- Lawrence High School

- Dartmouth College

- Death Year: 1963

- Death date: January 29, 1963

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Boston

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Robert Frost Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/robert-frost

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: December 1, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- The ear does it. The ear is the only true writer and the only true reader.

- I would have written of me on my stone: I had a lover's quarrel with the world.

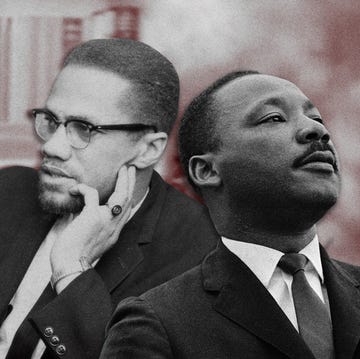

Civil Rights Activists

Ethel Kennedy

MLK Almost Didn’t Say “I Have a Dream”

Huey P. Newton

Martin Luther King Jr. Didn’t Criticize Malcolm X

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

30 Civil Rights Leaders of the Past and Present

Benjamin Banneker

Marcus Garvey

Madam C.J. Walker

Maya Angelou

- World Biography

Robert Frost Biography

Born: March 26, 1874 San Francisco, California Died: January 29, 1963 Boston, Massachusetts American poet

Robert Frost was a traditional American poet in an age of experimental art. He used New England expressions, characters, and settings, recalling the roots of American culture, to get at the common experience of all.

The early years

Robert Lee Frost was born in San Francisco, California, on March 26, 1874. His father, William, came from Maine and New Hampshire ancestry and had graduated from Harvard in 1872. He left New England and went to Lewistown, Pennsylvania, to teach. He married another teacher, Isabelle Moodie, a Scotswoman, and they moved to San Francisco, where the elder Frost became an editor and politician. Robert, their first child, was named for the Southern hero General Robert E. Lee (1807–1870).

When Frost's father died in 1884, his will requested that he be buried in New England. His wife and two children, Robert and Jeanie, went east for the funeral. Lacking funds to return to California, they settled in Salem, Massachusetts, where his grandfather had offered them a home. Eventually Mrs. Frost found a job teaching at a school.

Transplanted New Englander

As a young boy, Robert loved his mother reading to him. Her influence introduced him to a large variety of literature, and from this he was inspired to become an excellent reader. He lacked enthusiasm for school in his elementary years, but became a serious student and graduated from Lawrence High School as valedictorian (top in his class) and class poet in 1892. He enrolled at Dartmouth College but soon left. He had become engaged to Elinor White, classmate and fellow valedictorian, who was completing her college education. Frost moved from job to job, working in mills, at newspaper reporting, and at teaching, all the while writing poetry. In 1894 he sold his first poem, "My Butterfly," to the New York Independent. Overjoyed, he had two copies of a booklet of lyrics privately printed, one for his fiancée and one for himself. He delivered Elinor's copy in person but did not find her response to be enthusiastic. Thinking he had lost her, he tore up his copy and wandered south as far as the Dismal Swamp (from Virginia to North Carolina), even contemplating killing himself.

In 1895, however, Frost married Elinor and tried to make a career of teaching. He helped his mother run a small private school in Lawrence, Massachusetts, where his first son was born. He spent two years at Harvard, but undergraduate study proved difficult while raising a family. With a newborn daughter as well as a son to now raise, he decided to try chicken farming at Methuen, Massachusetts, on a farm purchased by his grandfather. In 1900, when his nervousness was diagnosed as a sign that he may possibly contract tuberculosis (a disease caused by bacteria that usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other organs in the body), he moved his poultry business to Derry, New Hampshire. There his first son soon died. In 1906 Frost was stricken with pneumonia (a disease that causes inflammation of the lungs) and almost died. A year later his fourth daughter died. This grief and suffering, as well as lesser frustrations in his personal and business life, turned Frost more and more to poetry. Once again he tried teaching, in Derry and then in Plymouth, New Hampshire.

Creation of the poet

In 1912, almost forty and with only a few poems published, Frost sold his farm and used an allowance from his grandfather to go to England and gamble everything on poetry. The family settled on a farm in Buckinghamshire, and Frost began to write. Ezra Pound (1885–1972), another American poet, helped him get published in magazines, and he met many people in literature that helped to inspire and further expand his knowledge of poetry.

Frost published A Boy's Will (1913), and it was well received. Though it contains some nineteenth-century expressions, the words and rhythms are generally informal and subtly simple.

North of Boston (1914) is more objective, made up mainly of blank verse (poetry without rhyme) monologues (long speeches, plays, or entertainment given by a single person) and dramatic narratives (stories or descriptions of events). North of Boston added to the success of A Boy's Will, and the two volumes announced the two modes of Frost's best poetry, the lyric (a poem telling of love or other emotions) and the narrative. Although immediately established as a nature poet, he did not glorify nature. He addressed not only its loveliness but also the isolation, harshness, and pain its New England inhabitants had to endure.

A public figure

When the Frosts returned to the United States in 1915, North of Boston was a bestseller. Sudden fame embarrassed Frost, who had always avoided crowds. He withdrew to a small farm in Franconia, New Hampshire, but financial need soon saw him responding to demands for readings and lectures. In 1915 and 1916 he was a Phi Beta Kappa (an organization made up of college students and graduates who have achieved a high level of academic excellence in studies of liberal arts and sciences) poet at Tufts College and at Harvard University. He conquered his shyness, developing a brief and simple speaking manner that made him one of the most popular performers in America and abroad.

In 1916 Frost published Mountain Interval, which brought together lyrics and narratives in his poetry. In 1917 Frost became one of the first poets-in-residence on an American campus. He taught at Amherst from 1917 to 1920, in 1918 receiving a master of arts, the first of many academic honors. The following year he moved his farm base to South Saftsbury, Vermont. In 1920 he cofounded the Bread Loaf School of English of Middlebury College, serving there each summer as lecturer and consultant. From 1921 to 1923 he was poet-in-residence at the University of Michigan.

Frost's Selected Poems and a new volume, New Hampshire, appeared in 1923. Frost received the first of four Pulitzer Prizes for the latter in 1924. Though the title poem does not present Frost at his best, the volume also contains such lyrics as "Fire and Ice," "Nothing Gold Can Stay," and "To Earthward."

Frost returned to Amherst for two years in 1923 and to the University of Michigan in 1925 and then settled at Amherst in 1926. In 1928 Frost published West Running Brook, in which he continued his use of tonal variations (changes in sound and rhythm) and a mixture of lyrics and narratives.

Frost visited England and Paris in 1928 and published his Collected Poems in 1930. In 1934 he suffered another painful loss with the death of his daughter Marjorie. He returned to Harvard in 1936 and in the same year published A Further Range.

Later work and personal tragedies

Because of Frost's weak lungs, his doctor ordered him south in 1936, and thereafter he spent his winters in Florida. Frost served on the Harvard staff from 1936 to 1937 and received an honorary doctorate. After his wife died of a heart attack in 1938, Frost resigned from the Amherst staff and sold his house. That same year he was elected to the Board of Overseers of Harvard College. In 1939 his second Collected Poems appeared, and he began a three-year stay at Harvard. In 1940 his only surviving son took his own life.

In 1945 Frost composed something new in A Masque of Reason, an updated version of the biblical story of Job. A Masque of Mercy (1947), was a companion verse drama (a dramatic poem) based on the biblical story of the prophet Jonah.

Frost's Complete Poems appeared in 1949, and in 1950 the U.S. Senate honored him on his seventy-fifth birthday. In 1957 he returned to England to receive doctoral degrees from Oxford and Cambridge. On his eighty-fifth birthday the Senate again honored him. In 1961, at the inauguration of John F. Kennedy (1917–1963), Frost recited "The Gift Outright," the first time a poet had honored a presidential inauguration. A final volume, In the Clearing, appeared in 1962.

On January 29, 1963, Frost died in Boston, Massachusetts, of complications following an operation. He was buried in the family plot in Old Bennington, Vermont.

For More Information

Brodsky, Joseph, Seamus Heaney, and Derek Walcott. Homage to Robert Frost. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1996.

Meyers, Jeffrey. Robert Frost: A Biography. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996.

Parini, Jay. Robert Frost: A Life. New York: Henry Holt, 1999.

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

Registration

Robert Frost: American Poet and Pulitzer Prize Laureate

Return to the united states and literary achievements, recognition and later works, collected poems and continued success.

Robert Frost was an American poet who became a classic and patriarch of American poetry during his lifetime. He was a four-time recipient of the Pulitzer Prize (1924, 1931, 1937, 1943). He was named after Robert E. Lee, the Confederate Army commander during the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865. Frost's father died of tuberculosis when he was 11 years old. The boy and his mother moved to Massachusetts, where Frost attended school in Lawrence. He enrolled in Dartmouth College in 1892 but soon left. From 1897 to 1899, he studied at Harvard University. Frost worked at a mill, helped his mother run a small private school in Lawrence, published a local newspaper, and even tried his hand at poultry farming. Discouraged by unsuccessful attempts to find his calling, he moved with his family to England in 1912 and settled in Beaconsfield for three years. In England, he experienced his first success when a publisher immediately published his manuscript of poetry, "A Boy's Will" (1913). His second book, "North of Boston," which was published the following year, achieved even greater success. Critics noticed similarities between Frost and the Georgian poets R. Graves, R. Brooke, W. Owen, E. Blanden, and E. Thomas. Thomas, who became a close friend of Frost's, significantly influenced his development as a poet.

In 1915, Frost returned to the United States and purchased a farm in New Hampshire. However, the income from the farm and the publication of his poems was not enough to support his family. To supplement his income, Frost gave lectures at universities and performed readings of his poetry. Frost's poetry did not persuade readers that the world was a haven of solace. The nature of New England became a familiar symbol and metaphor in Frost's poetry, as seen in his poems "Mowing," "Revelation," and "Complaint" from his collection "A Boy's Will," as well as in his monologue and dialogue poems "Mending Wall," "The Death of the Hired Man," "The Family Graveyard," and "The Wood-Pile" from "North of Boston." The poet listened to people's conversations and drew inspiration and themes from them. He considered no concerns to be "foreign" and felt connected to everything happening in the world, as evidenced by the poems in the collection "Mountain Interval" (1916), including "The Road Not Taken," "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening," "Birches," "Snow," and "A Conversation with a Friend."

Frost's next book, "New Hampshire" (1923), earned him his first Pulitzer Prize in 1924. The collection includes both narrative poems, such as "Paul's Wife" and "The Witch of Coos," and more concise and elegant meditative lyrics. Deep psychological insight and philosophical direction distinguish "Places, Blueberries, Fire and Ice," "Nothing Gold Can Stay," and Frost's most famous poem, included in all poetry anthologies, "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening." Frost's ability to harmonize the dynamics of New England residents' conversational speech with the metrical demands of free verse is masterfully displayed in the title poem of "West-Running Brook" (1928). Frost also had skill in handling rhymed verse, showcasing poetic conciseness that perfectly suited the reserved, laconic nature of a man who stoically bore the hardships of life.

Frost's first collected poems, "Collected Poems" (1930), encompassed his poetic work in its entirety and received the Pulitzer Prize in 1931. Two more collections, "A Further Range" (1936) and "A Witness Tree" (1942), brought him two additional Pulitzer Prizes. These books were followed by plays written in blank verse. According to critics, in "Masque of Reason" (1945), Frost did not fully realize his potential as he turned to the biblical character Job. However, his second play, "A Masque of Mercy" (1947), was considered more successful. Its modern interpretation of biblical characters deepened and expanded Frost's stoicism, transforming it into a thoughtful and mature philosophical position. Frost's later poetry collections "Steeple Bush" (1947) and "In the Clearing" (1962) include works that are on par with his more well-known early pieces. Frost's refusal to succumb to pain and suffering, his belief in the ability to resist circumstances, and his ability to find an adequate poetic form to express this refusal and belief explain why President John F. Kennedy asked Frost to recite his poem "The Gift Outright" at his inauguration ceremony in 1961. In 1962, Frost visited the Soviet Union.

© BIOGRAPHS

.png)

Life and Works of Robert Frost

The Risk of Spirit: An Artist's Life

Video can’t be displayed

This video is not available.

.jpeg)

Works by Frost

Books of poetry.

.jpeg)

Frost in His Own Words

Interviews and first-hand accounts.

Biographies

We use cookies to enable essential functionality on our website, and analyze website traffic. By clicking Accept you consent to our use of cookies. Read about how we use cookies.

We use cookies to enable essential functionality on our website, and analyze website traffic. Read about how we use cookies .

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our websites. You cannot refuse these cookies without impacting how our websites function. You can block or delete them by changing your browser settings, as described under the heading "Managing cookies" in the Privacy and Cookies Policy .

These cookies collect information that is used in aggregate form to help us understand how our websites are being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are.

- Humanities ›

- Literature ›

- Favorite Poems & Poets ›

Biography of Robert Frost

America's Farmer/Philosopher Poet

- Favorite Poems & Poets

- Poetic Forms

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- B.A., English and American Literature, University of California at Santa Barbara

- B.A., English, Columbia College

Robert Frost — even the sound of his name is folksy, rural: simple, New England, white farmhouse, red barn, stone walls. And that’s our vision of him, thin white hair blowing at JFK’s inauguration, reciting his poem “The Gift Outright.” (The weather was too blustery and frigid for him to read “Dedication,” which he had written specifically for the event, so he simply performed the only poem he had memorized. It was oddly fitting.) As usual, there’s some truth in the myth — and a lot of back story that makes Frost much more interesting — more poet, less icon Americana.

Early Years

Robert Lee Frost was born March 26, 1874 in San Francisco to Isabelle Moodie and William Prescott Frost, Jr. The Civil War had ended nine years previously, Walt Whitman was 55. Frost had deep US roots: his father was a descendant of a Devonshire Frost who sailed to New Hampshire in 1634. William Frost had been a teacher and then a journalist, was known as a drinker, a gambler and a harsh disciplinarian. He also dabbled in politics, for as long as his health allowed. He died of tuberculosis in 1885, when his son was 11.

Youth and College Years

After the death of his father, Robert, his mother and sister moved from California to eastern Massachusetts near his paternal grandparents. His mother joined the Swedenborgian church and had him baptized in it, but Frost left it as an adult. He grew up as a city boy and attended Dartmouth College in 1892, for just less than a semester. He went back home to teach and work at various jobs including factory work and newspaper delivery.

First Publication and Marriage

In 1894 Frost sold his first poem, “My Butterfly,” to The New York Independent for $15. It begins: “Thine emulous fond flowers are dead, too, / And the daft sun-assaulter, he / That frighted thee so oft, is fled or dead.” On the strength of this accomplishment, he asked Elinor Miriam White, his high school co-valedictorian, to marry him: she refused. She wanted to finish school before they married. Frost was sure that there was another man and made an excursion to the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia. He came back later that year and asked Elinor again; this time she accepted. They married in December 1895.

Farming, Expatriating

The newlyweds taught school together until 1897, when Frost entered Harvard for two years. He did well, but left school to return home when his wife was expecting a second child. He never returned to college, never earned a degree. His grandfather bought a farm for the family in Derry, New Hampshire (you can still visit this farm). Frost spent nine years there, farming and writing — the poultry farming was not successful but the writing drove him on, and back to teaching for a couple more years. In 1912, the Frost gave up the farm, sailed to Glasgow, and later settled in Beaconsfield, outside London.

Success in England

Frost’s efforts to establish himself in England were immediately successful. In 1913 he published his first book, A Boy’s Will , followed a year later by North of Boston . It was in England that he met such poets as Rupert Brooke, T.E. Hulme and Robert Graves, and established his lifelong friendship with Ezra Pound, who helped to promote and publish his work. Pound was the first American to write a (favorable) review of Frost’s work. In England Frost also met Edward Thomas, a member of the group known as the Dymock poets; it was walks with Thomas that led to Frost’s beloved but “tricky” poem, “The Road Not Taken.”

The Most Celebrated Poet in North America

Frost returned to the U.S. in 1915 and, by the 1920s, he was the most celebrated poet in North America, winning four Pulitzer Prizes (still a record). He lived on a farm in Franconia, New Hampshire, and from there carried on a long career writing, teaching and lecturing. From 1916 to 1938, he taught at Amherst College, and from 1921 to 1963 he spent his summers teaching at the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference at Middlebury College, which he helped found. Middlebury still owns and maintains his farm as a National Historic site: it is now a museum and poetry conference center.

Upon his death in Boston on January 29, 1963, Robert Frost was buried in the Old Bennington Cemetery, in Bennington, Vermont. He said, “I don’t go to church, but I look in the window.” It does say something about one’s beliefs to be buried behind a church, although the gravestone faces in the opposite direction. Frost was a man famous for contradictions, known as a cranky and egocentric personality – he once lit a wastebasket on fire on stage when the poet before him went on too long. His gravestone of Barre granite with hand-carved laurel leaves is inscribed, “I had a lover’s quarrel with the world

Frost in the Poetry Sphere

Even though he was first discovered in England and extolled by the archmodernist Ezra Pound, Robert Frost’s reputation as a poet has been that of the most conservative, traditional, formal verse-maker. This may be changing: Paul Muldoon claims Frost as “the greatest American poet of the 20th century,” and the New York Times has tried to resuscitate him as a proto-experimentalist: “ Frost on the Edge ,” by David Orr, February 4, 2007 in the Sunday Book Review.

No matter. Frost is secure as our farmer/philosopher poet.

- Frost was actually born in San Francisco.

- He lived in California till he was 11 and then moved East — he grew up in cities in Massachusetts.

- Far from a hardscrabble farming apprenticeship, Frost attended Dartmouth and then Harvard. His grandfather bought him a farm when he was in his early 20s.

- When his attempt at chicken farming failed, he served a stint teaching at a private school and then he and his family moved to England.

- It was while he was in Europe that he was discovered by the US expat and Impresario of Modernism, Ezra Pound, who published him in Poetry .

“Home is the place where, when you have to go there, They have to take you in....” --“The Death of the Hired Man”

“Something there is that doesn’t love a wall....” --“ Mending Wall ”

“Some say the world will end in fire, Some say in ice.... --“ Fire and Ice”

A Girl’s Garden

Robert Frost (from Mountain Interval , 1920)

A neighbor of mine in the village Likes to tell how one spring When she was a girl on the farm, she did A childlike thing.

One day she asked her father To give her a garden plot To plant and tend and reap herself, And he said, “Why not?”

In casting about for a corner He thought of an idle bit Of walled-off ground where a shop had stood, And he said, “Just it.”

And he said, “That ought to make you An ideal one-girl farm, And give you a chance to put some strength On your slim-jim arm.”

It was not enough of a garden, Her father said, to plough; So she had to work it all by hand, But she don’t mind now.

She wheeled the dung in the wheelbarrow Along a stretch of road; But she always ran away and left Her not-nice load.

And hid from anyone passing. And then she begged the seed. She says she thinks she planted one Of all things but weed.

A hill each of potatoes, Radishes, lettuce, peas, Tomatoes, beets, beans, pumpkins, corn, And even fruit trees

And yes, she has long mistrusted That a cider apple tree In bearing there to-day is hers, Or at least may be.

Her crop was a miscellany When all was said and done, A little bit of everything, A great deal of none.

Now when she sees in the village How village things go, Just when it seems to come in right, She says, “I know!

It’s as when I was a farmer——” Oh, never by way of advice! And she never sins by telling the tale To the same person twice.

- A Guide to Robert Frost's "The Road Not Taken"

- 10 Classic Poems for Halloween

- 10 Classic Poems on Gardens and Gardening

- Robert Frost's 'Acquainted With the Night'

- Understanding 'The Pasture' by Robert Frost

- Presidential Inauguration Poems

- Poets Laureate of the U.S.A.

- William Wordsworth

- Reading Notes on Robert Frost’s Poem “Nothing Gold Can Stay”

- A Classic Collection of Bird Poems

- 18 Classic Poems of the Christmas Season

- A Collection of Classic Love Poetry for Your Sweetheart

- 7 Classic Poems for Fathers

- 41 Classic and New Poems to Keep You Warm in Winter

- Biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Poet and Activist

- 14 Classic Poems Everyone Should Know

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Agriculture

- Armed forces and intelligence services

- Art and architecture

- Business and finance

- Education and scholarship

- Individuals

- Law and crime

- Manufacture and trade

- Media and performing arts

- Medicine and health

- Religion and belief

- Royalty, rulers, and aristocracy

- Science and technology

- Social welfare and reform

- Sports, games, and pastimes

- Travel and exploration

- Writing and publishing

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Frost, robert.

- Stanley Burnshaw

- https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1600598

- Published in print: 1999

- Published online: February 2000

Robert Frost.

Frost, Robert ( 26 March 1874–29 January 1963 ), poet , was born Robert Lee Frost in San Francisco to Isabelle Moodie, of Scottish birth, and William Prescott Frost, Jr., a descendant of a Devonshire Frost who had sailed to New Hampshire in 1634. The father was a former teacher turned newspaper man, a hard drinker, a gambler, and a harsh disciplinarian, who fought to succeed in politics for as long as his health allowed. In the wake of his death (as a consumptive) in his thirty-sixth year, his impoverished widow, with the help of funds from her father-in-law, moved east. She resumed her teaching career in the fall of 1885 in Salem, New Hampshire, where Robert and his younger sister were enrolled in the fifth-grade class. Soon he was playing baseball, trapping animals, climbing birches. And his mother, who had filled his early years with Shakespeare, Bible stories, and myths, was reading aloud from Tom Brown’s School Days , Burns, Ralph Waldo Emerson , Wordsworth, and Percy’s Reliques . Before long he was memorizing poetry and reading books on his own.

Frost’s high school years in Lawrence, Massachusetts, marked a further change. Greek and Latin delighted him; at the end of the first year he was head of his class. An older student, Carl Burell, introduced him to botany and astronomy. More important, Frost became a promising writer: his poem “La Noche Triste,” inspired by William H. Prescott ’s History of the Conquest of Mexico (1843), appeared in the April 1890 issue of the high school Bulletin , of which he was soon made editor. He joined the debating society, played on the football team, and again was head of his class. At the beginning of his senior year he fell in love with Elinor White, who had also published poetry in the Bulletin . On commencement day (1892) they shared valedictory honors and, before summer ended, pledged themselves to each other in a secret ritual.

In the fall they went their separate ways: Elinor to St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, Frost to Dartmouth on a scholarship and with his grandfather’s aid. Though he relished his courses in Latin and Greek and his own wide reading of English verse, in particular Francis Turner Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of the Best Songs and Lyrical Poems in the English Language , the campus life dismayed him. Isolated and restless, he quit at the end of December, being needed, he said, to take over his mother’s unruly eighth-grade class. He was nursing the hope that Elinor might give up school to marry him, but when she returned in April his attempts to persuade her failed.

After working for months as a trimmer of lamps in a woolen mill in Lawrence, Frost turned to teaching in grade school, while also writing poetry. At the end of the term, startling news greeted him: the New York Independent had accepted “My Butterfly: An Elegy,” with a stipend of $15. His first professionally published poem would appear in November—he could earn his living as a writer! Once again he implored Elinor to marry him; once again she refused. Convinced there was now another suitor, he engaged a printer to make two leather-bound, gold-stamped copies of Twilight , each containing five of his poems. He took the train to Canton, knocked at her door, and handed her his gift. The inimically cool reception hurled him into despair. Pained and distraught, he destroyed his copy and went home. Still distraught, on 6 November he set out for the Dismal Swamp in Virginia—to throw his life away? punish Elinor? make her relent? On 30 November 1894, frightened and worn, he was back in Lawrence. Before long he became a reporter, then returned to teaching. Elinor, having finished college, also taught in his mother’s private school. Then at long last, on 19 December 1895, they were married by a Swedenborgian pastor. Nine months later, Elliot, a son, was born.

They both kept working as teachers, and Frost kept publishing poems. In the fall of 1897, thanks to his grandfather’s loan, Frost, at age twenty-three, entered Harvard in the hope of becoming a high school teacher of Latin and Greek. Certain courses proved meaningful, most of all in the classics and geology, but also in philosophy with Hugo Münsterberg , who assigned Psychology: Briefer Course by William James , Frost’s “greatest inspiration,” then absent on leave. In March 1899, however, severe chest and stomach pains combined with worries about his ailing mother and pregnant wife forced him to leave Harvard.

Medical warnings—the threat of tuberculosis—drove Frost from the indoor life of teaching. In May 1900, with his grandfather’s help, he rented a poultry farm in Methuen. Two months later, Elliot, the Frosts’ three-year-old, became gravely ill with cholera infantum ; on 8 July he died. Frost flailed himself for not having summoned a doctor in time, believing that God was punishing him by taking his child away. Elinor, silent for days, at last let fly at him for his “self-centered senselessness” in believing that any such thing as a god’s benevolent concern for human affairs could exist; life was hateful and the world evil, but with a fourteen-month-old daughter, Lesley, to care for, they would have to go on. And when their landlord ordered them to leave by fall, Elinor took matters in hand. She persuaded Grandfather Frost to buy for their use the thirty-acre farm that her mother had found in Derry, New Hampshire, and to arrange, in addition, for Carl Burell, Frost’s high school friend, to move in to help with the chores.

The “Derry Years” (1900–1911) were especially creative ones, bringing forth—complete or in draft—nearly all of A Boy’s Will (1913), much, if not most, of North of Boston (1914), many poems of Mountain Interval (1916), as well as some that appeared in each of his later books. Yet at times in the first two years he was deeply depressed: in November 1900 his mother died; in July 1901, his other firm supporter, Grandfather Frost. But the latter’s will bequeathed to his grandson an immediate annuity of $500 and after ten years an annuity of $800 and the deed to the Derry property.

Frost continued to write at night: poems and articles for poultry journals. He enjoyed working the farm by day and learning about the countryside and the lives of its people. By 1906, though fairly well off compared to his neighbors, yet with four children under seven, he was pressed for money. With the aid of a pastor-friend and a school trustee who admired his poems, he obtained a position at the nearby Pinkerton Academy, which he held with outstanding success. A pedagogic original, he introduced a conversational classroom style. He directed students in plays he adapted from Marlowe, Milton, Sheridan, and Yeats. He revised the English curriculum. And besides teaching seven classes a day, he helped with athletics, the student paper, and the debating team. At the end of five years, utterly exhausted, he resigned.

In the fall of 1911 he was teaching again, part time in the Plymouth, New Hampshire, Normal School. But in December he announced to his editor-friend at the Independent , Susan Ward, that “the long deferred forward movement you have been living in wait for is to begin next year.” In July 1912 he started making plans for a radical change of scene. When he suggested England to Elinor as “the place to be poor and to write poems, ‘Yes,’ she cried, ‘let’s go over and live under thatch.’ ”

On 2 September 1912 the Frosts arrived in London. They stayed there briefly before moving into “The Bungalow” in Beaconsfield, where they would live for eighteen months. Elinor, charmed by the “dear little cottage” and its long grassy yard, strolled the countryside with the children; Frost traveled at will to London—forty minutes by train—roaming the streets, the bookshops, “everywhere.” Before long he was finishing the manuscript of A Boy’s Will that he had brought to England and adding a few new poems. In October the book was accepted by David Nutt for publication the following March.

Through the next few months Frost was seized by a powerful surge of creativity, producing twelve or more lengthy poems, each strikingly different from the brooding narratives of A Boy’s Will : dialog-narratives in a style of “living” speech new to the language, exploring the inward lives of ordinary people in the New England countryside. By April 1913, most of (if not all) the poems that would constitute North of Boston had been written.

At the January 1913 opening of Monro’s Poetry Bookshop Frost was urged by the poet Frank Flint to call on Ezra Pound (whom he had never heard of), a reviewer for various journals. Frost waited until 13 March, about a week before A Boy’s Will was to appear. At Pound’s insistence, they walked to the publisher’s office for a copy. On their return, Pound started reading at once, then told his guest to “run along home” so he could write his review for Poetry , a new American monthly. In the next few weeks, thanks to Pound and Flint, Frost came to meet some of the best-known writers then living in England, including Yeats, H.D. ( Hilda Doolittle ), Richard Aldington, and Ford Madox Ford.

A Boy’s Will , finally issued on 1 April 1913, elicited favorable but qualified reviews. Chronicling the growth of a youth from self-centered idealism to maturity and acceptance of loss, the thirty-two lyrics offered few hints of the masterful volumes to come, except for those in “Mowing,” “Storm Fear,” and scattered passages. Yeats pronounced the poetry “the best written in America for some time,” leading Elinor to “hope”—in vain—that “he would say so publicly.” Happily, in the fall, on his return from a family vacation in Scotland, Frost was greeted by two extraordinary tributes in the Nation and the Chicago Dial and a superb review in the Academy .

During the next few months, Frost came to know the writers Robert Bridges, Walter de la Mare, W. H. Davies, and Ralph Hodgson; the Georgian poets Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Gibson, Lascelles Abercrombie; and the essayist and poet Edward Thomas, who would become his bosom friend. With Flint and T. E. Hulme he discussed poetics, having spoken in letters to his Pinkerton friends John Bartlett and Sidney Cox of “the sounds of sense with all their irregularity of accent across the regular beat of the metre” and “the sentence sound [that] often says more than the words.” He also wrote that he wanted not “a success with the critical few” but “to get outside to the general reader who buys books by the thousands.”

In April, badly strained for funds, Frost moved his family 100 miles northwest of London to an ancient cottage, not far from Abercrombie’s and Gibson’s, in the rolling Gloucestershire farmland near Dymock. On 15 May North of Boston appeared, to be hailed in June by important reviews, particularly those by Abercrombie (“there will never be,” said Frost, “any other just like it”), Ford Madox Ford (“an achievement much finer than Whitman’s”), Richard Aldington (“it would be very difficult to overpraise it”), and Edward Thomas (“Only at the end of the best pieces, such as ‘The Death of the Hired Man,’ ‘Home Burial,’ ‘The Black Cottage,’ and ‘The Wood-pile,’ do we realize that they are masterpieces of a deep and mysterious tenderness”). By August, Frost’s reputation as a leading poet had been firmly established in England, and Henry Holt of New York had agreed to publish his books in America. By the end of 1914, however, financial need forced him to leave Britain.

When Frost and his family returned to the United States in February, he was hailed as a leading voice of the “new poetry” movement. Holt’s editor introduced him to the staff of the New Republic , which had just published a favorable review of North of Boston , and Tufts College invited him to be its Phi Beta Kappa poet. Before the year’s end, he had met with Edwin Arlington Robinson , William Dean Howells , Louis Untermeyer (who would become his intimate friend), Ellery Sedgwick of the Atlantic Monthly , and other literary figures. In the following year he was made Phi Beta Kappa poet at Harvard and elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Mountain Interval , which appeared in November 1916, offered readers some of his finest poems, such as “Birches,” “Out, Out—,” “The Hill Wife,” and “An Old Man’s Winter Night.”

Frost’s move to Amherst in 1917 launched him on the twofold career he would lead for the rest of his life: teaching whatever “subjects” he pleased at a congenial college (Amherst, 1917–1963, with interruptions; the University of Michigan, 1921–1923, 1925–1926; Harvard, 1939–1943; Dartmouth, 1943–1949) and “barding around,” his term for “saying” poems in a conversational performance. Audiences flocked to listen to the “gentle farmer-poet” whose platform manner concealed the ever-troubled, agitated private man who sought through each of his poems “a momentary stay against confusion.” In the great short lyrics of New Hampshire (1923) and West-Running Brook (1928)—such as “Fire and Ice,” “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” and the title poem of the latter book—a bleak outlook on life persuasively emerges from the combination of dramatic tension and nature imagery freighted with ambiguity. Only the will to create form, the poet in effect says, can stave off the nothingness that confronts us as mortal beings.

In 1930 Frost won a second Pulitzer Prize for Collected Poems —the first had been won by New Hampshire —and in the next few years, other prizes and honors, including the Charles Eliot Norton Professorship of Poetry at Harvard. However, when A Further Range appeared in 1936, several influential leftist critics, unaware that Frost had “twice been approached” by the New Masses “to be their proletarian poet,” attacked him for his conservative political views, ignoring the bitter meanings in “Provide, Provide” and such master poems as “Desert Places,” “Design,” and “Neither Out Far nor In Deep.” A Further Range earned him a third Pulitzer Prize in May 1937. Ten months later, on 26 March 1938, Elinor died and his world collapsed. Four years before, in the wake of their daughter Marjorie’s death, they had helped each other bear the grief. Alone now, wracked in misery and guilty over his sometimes insensitive behavior toward Elinor, he hoped to find calm through his children, but Lesley’s ragings only deepened his pain. For some time he continued to teach, then resigned his position, sold his Amherst house, and returned to his farm. In July Theodore Morrison invited him to speak at the Breadloaf Writers’ Conference in August. Frost’s lectures enthralled his listeners, but at times his erratic public behavior drew worried attention. To the great relief of his friends, Kathleen Morrison, the director’s wife, stepped in to offer him help with his affairs. He accepted at once and made her his official secretary-manager.

Weeks before, however, Kathleen had called at his farm to invite him to visit her at a nearby summer house. Before long he proposed marriage, but she insisted on secrecy, on maintaining appearances. “We wanted to marry,” he told Stanley Burnshaw, his editor in the 1960s. “It was all decided. But you know how matters seem at times—others to think of … It was thought best,” he repeated, “It was thought best”—marriage without benefit of clergy, an altered way of life. He continued to bard around and to teach, residing from January through March at “Pencil Pines,” his newly built Miami retreat; at his Cambridge house until late May; then in Ripton, near Breadloaf, for the summer; and in Cambridge again through December.

During the 1940s Frost published four new books: A Witness Tree (1942), inscribed “To K.M./For Her Part in It,” containing some of his finest poems, among them “The Most of It” and “The Silken Tent,” and for which he received his fourth Pulitzer Prize; two deceptively playful blank verse dialogs, A Masque of Reason (1945) and A Masque of Mercy (1947), on the relationship between God and man, to be “taken” in light of his statements on “irony . . . a kind of guardedness” and “style … the way the man takes himself … If it is with outer humor, it must be with inner seriousness”; and fourth, Steeple Bush (1947), his weakest volume, although it included “Directive,” one of Frost’s major poems. None but his intimates knew of the decade’s griefs: his son Carol’s suicide in 1940, his daughter Irma’s placement in a mental hospital in 1947.

In the last fourteen years of his life Frost was the most highly esteemed American poet of the twentieth century, having received forty-four honorary degrees and a host of government tributes, including birthday greetings from the Senate, a congressional medal, an appointment as honorary consultant to the Library of Congress, and an invitation from John F. Kennedy to recite a poem at his presidential inauguration. Thrice, at the State Department’s request, he traveled on good-will missions: to Brazil (1954), to Britain (1957), and to Greece (1961, on his return from Israel, where he had lectured at the Hebrew University).

More important for Frost as an artist and for his readers were the changed perceptions of his works, which began with Randall Jarrell ’s 1947 essay “The Other Frost.” Jarrell saw him as “the subtlest and saddest of poets” whose “extraordinary strange poems express an attitude that, at its most extreme, makes pessimism a hopeful evasion.” Twelve years later Lionel Trilling hailed Frost at his eighty-fifth birthday dinner for his “representation of the terrible actualities of life in a new way,” for though “the manifest America of [his] poems may be pastoral, the actual America is tragic.” And two years earlier, in London at the English-Speaking Union, T. S. Eliot (who in 1922 had dismissed Frost’s verse as “unreadable”) toasted him as “perhaps the most eminent, the most distinguished Anglo-American poet now living,” whose “kind of local feeling in poetry … can go without universality: the relation of Dante to Florence, … of Robert Frost to New England.”

In the Clearing , Frost’s ninth and last collection of poems, appeared on 26 March 1962, the date of his eighty-eighth birthday dinner in Washington, attended by some 200 guests who heard Justices Earl Warren and Felix Frankfurter , Adlai Stevenson , Mark Van Doren , and Robert Penn Warren speak in his honor. Five months later, at the president’s request, Frost made a twelve-day trip to the USSR, where he met with fellow writers and with Premier Nikita Khrushchev. On his return, “bone tired” and exhausted after eighteen sleepless hours, he made some ill-considered public remark, which was taken as a slur on both Khrushchev and President Kennedy. To Frost’s deep dismay, the president did not receive him.

On 2 December at the Ford Forum Hall in Boston Frost made his last address and, though admitting he felt a bit tired, he stayed the evening through. In the morning he felt much too ill to keep his doctor’s appointment. After considerable wrangling, he agreed to enter a hospital “for observation and tests.” He remained in its care until his death in the early hours of 29 January 1963. Tributes poured in from all over the land and from abroad. A small private service on the 31st at Harvard’s Memorial Church for family members and friends was followed by a public one on 17 February at the Amherst College Chapel, where 700 guests listened to Mark Van Doren’s recital of eleven Frost poems he had chosen for the occasion. Eight months later, at the October dedication of the Robert Frost Library at Amherst, President Kennedy paid tribute to the poetry, to “its tide that lifts all spirits,” and to the poet “whose sense of the human tragedy fortified him against self-deception and easy consolation.”

Within a decade, however, the poet’s public image was shattered by the appearance of the second volume of Lawrance Thompson’s authorized biography, Robert Frost: The Years of Triumph, 1915–1937 (1970), which reviewers took at face value to be an accurate account of a man whom Helen Vendler deemed a “monster of egotism” ( New York Times Book Review , 9 Aug. 1970). Although Frost later came to have grave misgivings about his choice, he had designated Thompson his official biographer in 1939. For whatever reason, the poet felt unable to renounce that decision despite his awareness of Thompson’s frequently unsympathetic, even hostile constructions of his attitudes and conduct. Although reviewers perceived in Thompson, as Vendler put it, “an affectation of fairness,” they tended to subscribe, nevertheless, to the “monster-myth” that poisoned Frost’s reputation. Evidence that he was not a wrecker of others’ lives was soon at hand in the form of The Family Letters of Robert and Elinor Frost , edited by Arnold Grade (1972). More than a decade would pass before the tide was turned: first by W. H. Pritchard’s Frost: A Literary Life Reconsidered (1984) and then by Stanley Burnshaw’s Robert Frost Himself (1986), which enabled Publishers’ Weekly to state that “the unfortunately influential ‘monster-myth’ stands here convincingly corrected.”

Bibliography

Significant collections of Frost materials are in the Jones Library in Amherst, Mass., Amherst College Library, Dartmouth College Library, University of Virginia Library, and University of Texas Library, Austin. In addition to the volumes by Frost cited in the text above, editions of his writings include Collected Poems, Prose & Plays , ed. Richard Poirier and Mark S. Richardson (1995), and “The Collected Prose of Robert Frost,” ed. M. S. Richardson (Ph.D. diss., Rutgers Univ., 1993). Additional correspondence appears in Letters of Robert Frost to Louis Untermeyer , ed. Louis Untermeyer (1963), and Selected Letters of Robert Frost , ed. Lawrance Thompson, 1964. Frost’s spoken words are transcribed in Robert Frost Speaks , ed. Daniel Smythe (1964); Robert Frost, Life and Talks-Walking , ed. Louis Mertins (1965); Interviews with Robert Frost , ed. E. C. Lathem (1966); Robert Frost: A Living Voice , ed. Reginald Cook (1974); and Newdick’s Season of Frost , ed. William Sutton (1976).

Biographical materials include L. Thompson’s typescript “Notes on Robert Frost” (1962; Alderman Library, Univ. of Virginia); Sidney Cox, A Swinger of Birches , with an introduction by Robert Frost (1957); Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant, Robert Frost: The Trial by Existence (1960); Margaret Bartlett Anderson, Robert Frost and John Bartlett: The Record of a Friendship (1963); F. D. Reeve, Robert Frost in Russia (1964); Wade Van Dore, Robert Frost and Wade Van Dore , rev. and ed. Thomas Wetmore (1987); John E. Walsh, Into My Own: The English Years of Robert Frost (1988); and Lesley Lee Francis (his granddaughter), The Frost Family’s Adventure in Poetry (1994). In addition to The Years of Triumph volume discussed above, L. Thompson’s official biography comprises Robert Frost: The Early Years, 1874–1915 (1966) and Robert Frost: The Later Years, 1938–1963 , with R. H. Winnick (1976). Assessments and criticism of note include Richard Thornton, ed., Recognition of Robert Frost (1937); Reuben Brower, The Poetry of Robert Frost (1963); Jac Tharpe, ed., Frost: Centennial Essays (3 vols., 1974–1978); R. Poirier, Robert Frost: The Work of Knowing (1977); and M. S. Richardson, The Ordeal of Robert Frost: The Poet and His Poetics (1997).

Online Resources

- Robert Frost http://www.poets.org/lit/poet/rfrosfst.htm From the Academy of American Poets.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1803-1882), lecturer and author

- Prescott, William Hickling (1796-1859), historian

- Münsterberg, Hugo (1863-1916), psychologist

- James, William (1842-1910), philosopher and psychologist

- Pound, Ezra (1885-1972), poet and critic

- Doolittle, Hilda (1886-1961), poet and novelist

- Holt, Henry (1840-1926), book publisher

- Robinson, Edwin Arlington (1869-1935), poet

- Howells, William Dean (1837-1920), author

- Untermeyer, Louis (1885-1977), poet and anthologist

- Sedgwick, Ellery (27 February 1872–21 April 1960), magazine editor

- Kennedy, John Fitzgerald (29 May 1917–22 November 1963), thirty-fifth president of the United States

- Jarrell, Randall (1914-1965), poet and critic

- Trilling, Lionel (1905-1975), literary critic and author

- Eliot, T. S. (26 September 1888–04 January 1965), poet, critic, and editor

- Warren, Earl (1891-1974), chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, governor of California, and attorney general of California

- Frankfurter, Felix (15 November 1882–22 February 1965), associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

- Stevenson, Adlai Ewing, II (1900-1965), governor, diplomat, and two-time candidate for president

- Van Doren, Mark (13 June 1894–10 December 1972), writer and professor of English

- Warren, Robert Penn (24 April 1905–15 September 1989), author and educator

Related articles in Companion to United States History on Oxford Reference

- Frost, Robert, (26 March 1874–29 Jan. 1963), Poetry Consultant to the Library of Congress, since 1958; Member of American Academy of Arts and Letters; Member of American Philosophical Society; George Ticknor Fellow in Humanities, Dartmouth College in Who Was Who

- Frost, Robert in Oxford Music Online

External resources

- Library of Congress Poets Laureate

Printed from American National Biography. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 23 December 2024

- Cookies Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.158.225.244]

- 195.158.225.244

Character limit 500 /500

COMMENTS

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 - January 29, 1963) was an American poet. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloquial speech, [2] Frost frequently wrote about settings from rural life in New England in the early 20th century, using them to examine complex social and philosophical themes. [3]Frequently honored during his lifetime, Frost is the only ...

Robert Frost (born March 26, 1874, San Francisco, California, U.S.—died January 29, 1963, Boston, Massachusetts) was an American poet who was much admired for his depictions of the rural life of New England, his command of American colloquial speech, and his realistic verse portraying ordinary people in everyday situations. He was the most highly honored American poet of the 20th century ...

Robert Frost was an American poet who depicted realistic New England life through language and situations familiar to the common man. He won four Pulitzer Prizes for his work and spoke at John F ...

Robert Frost Biography ; Robert Frost Biography. Born: March 26, 1874 San Francisco, California Died: January 29, 1963 Boston, Massachusetts ... (1914) is more objective, made up mainly of blank verse (poetry without rhyme) monologues (long speeches, plays, or entertainment given by a single person) and dramatic narratives (stories or ...

Robert Frost: American Poet and Pulitzer Prize Laureate Robert Frost was an American poet who became a classic and patriarch of American poetry during his lifetime. He was a four-time recipient of the Pulitzer Prize (1924, 1931, 1937, 1943). He was named after Robert E. Lee, the Confederate Army commander during the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865.

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 - January 29, 1963) was born in San Francisco to William Prescott Frost Jr. and Isabelle Moodie. His father, a hustling journalist, died in 1885, leaving his widow and two children with hardly enough money to make it back to Lawrence, Massachusetts. There, young Frost's paternal grandfather, William Prescott ...

Frost had deep US roots: his father was a descendant of a Devonshire Frost who sailed to New Hampshire in 1634. William Frost had been a teacher and then a journalist, was known as a drinker, a gambler and a harsh disciplinarian. He also dabbled in politics, for as long as his health allowed. He died of tuberculosis in 1885, when his son was 11.

Robert Lee Frost was an American poet best known for his vivid poems describing rural life in England. He wrote descriptive poems about ordinary people going about their lives with a philosophical undertone. ... Robert Frost lived a long life and died on January 29, 1963, due to complications from prostate surgery. ...

Frost, Robert (26 March 1874-29 January 1963), poet, was born Robert Lee Frost in San Francisco to Isabelle Moodie, of Scottish birth, and William Prescott Frost, Jr., a descendant of a Devonshire Frost who had sailed to New Hampshire in 1634.The father was a former teacher turned newspaper man, a hard drinker, a gambler, and a harsh disciplinarian, who fought to succeed in politics for as ...

Robert Frost Biography - Robert Frost (1874-1963) was born in San Francisco, California. His father William Frost, a journalist and an ardent Dem ... Frost travelled in 1962 in the Soviet Union as a member of a goodwill group. He had a long talk with Premier Nikita Khrushchev, whom he described as "no fathead"; as smart, big and "not a coward." ...