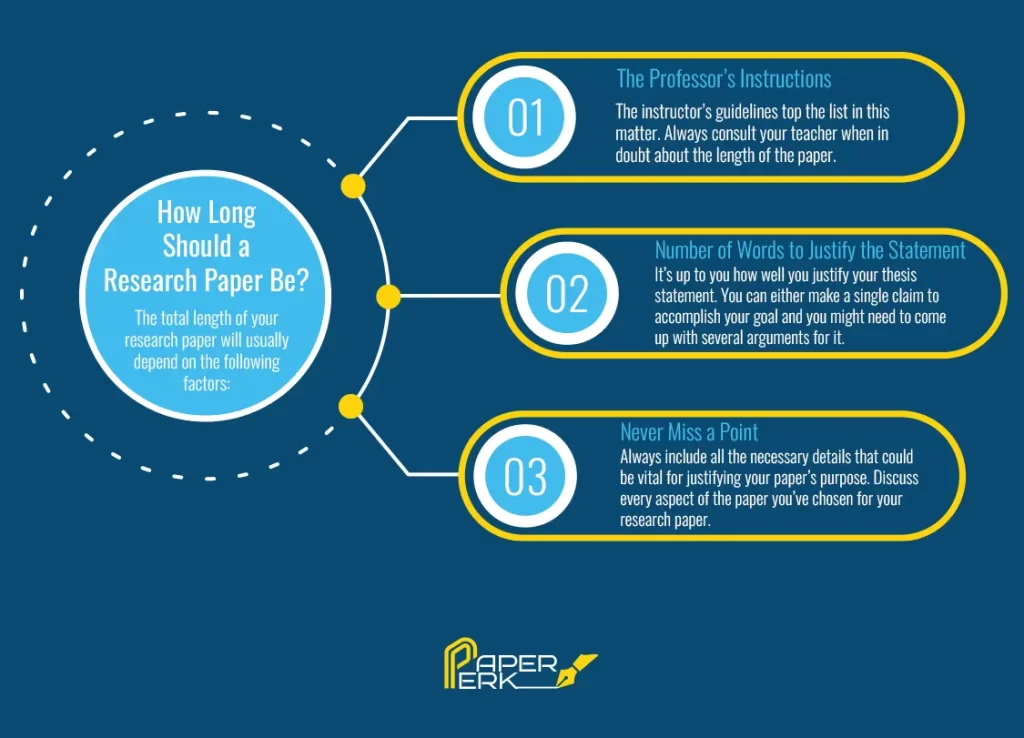

How Long Should a Research Paper Be?

How Long Should A Research Paper Be? An Overview

In short, research paper's average length can range from 1,500 words for research proposals and case studies - all the way to 100,000 words for large dissertations.

Research, by its nature of being complex, requires a careful and thorough elucidation of facts, notions, information, and the like - which is all reflected in its most optimal length.

Thus, one of the critical points that you need to focus on when writing either a complex research paper or a less complex research paper is your objective and how you can relay the latter in a particular context. Say you are writing a book review. Since you will only need to synthesize information from other sources to solidify your claim about a certain topic, you will perhaps use paraphrasing techniques, which offer a relatively lower word count when compared to a full-blown descriptive research paper.

Even when both types of research differ in word counts, they can effectively attain their objectives, given the different contexts in which they are written and constructed.

Certainly, when asked about how long is a research paper, it surely depends on the objective or the type of research you will be using. Carrying out these objectives will warrant you to do certain paper writing tasks and techniques that are not necessarily long or short when you compare them to other research types.

At Studyfy, we care for the attainment of your research objectives. We understand that achieving such will contribute to the success of your research completion. While maintaining the ideal word count for a research paper, you are in a meaningful position to understand the various elements that can enrich your paper, even if it looks overwhelming.

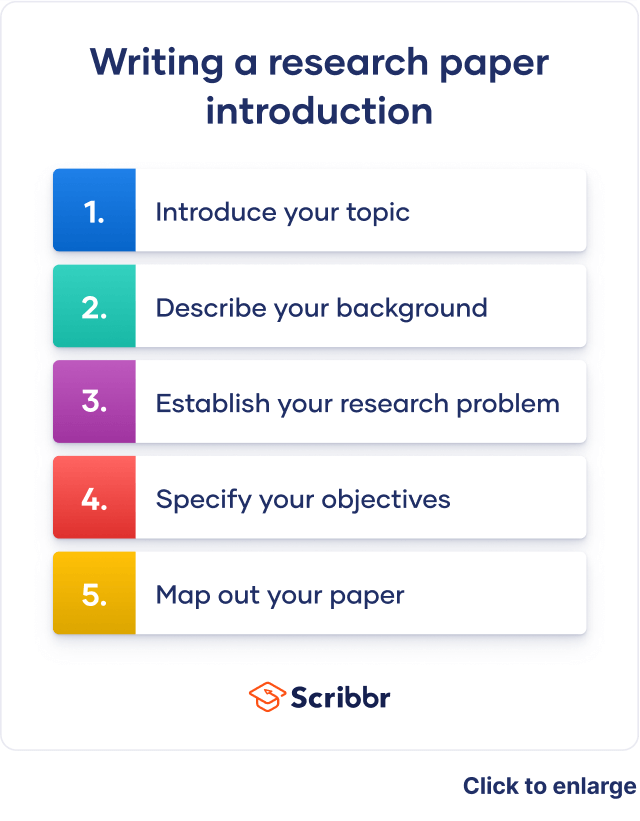

How Long Should the Introduction of a Research Paper Be?

The research introduction section most likely occupies approximately 30-40% of the entire research paper.

The introduction of a regular academic paper can total 1750-2000 words depending on the research type and complexity of the research niche or topic. That is why, in writing this section, you must enrich the content of your paper while maintaining readability and coherence for the benefit of your readers.

The introduction houses the background of the study. This is the part of the paper where the entire context of the paper is established. We all know that the research context is important as it helps the readers understand why the paper is even conducted in the first place. Thus, the impression of having a well-established context can only be found in the introduction. Now that we know the gravity of creating a good introduction, let us now ask how long this section should be.

Generally speaking, the paper’s introduction is the longest among all the sections. Aside from establishing the context, the introduction must house the historical underpinnings of the study (important for case studies and ethnographic research), salient information about all the variables in the study (including their relationship with other variables), and related literature and studies that can provide insight into the novelty and peculiarities of the current research project.

| Subsection | Description | Percentage of Introduction | Word Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context Establishment and Introduction of Key Terms | Articulates the background of the study, including historical, social, economic, psychological contexts, and defines key terms both operationally and theoretically. | 20% | 350-500 words |

| Related Literature and Studies | Critiques and integrates existing literature and studies to highlight the research gap that the study aims to fill. | 25% | 450-600 words |

| Thesis Statement | A straightforward statement or a couple of sentences relaying the identified research gap. | 5% | 90-100 words |

| Objectives or Research Questions | Outlines the aims of the study, highlighting the inquiries concerning the relationship between the variables and the progress to fill in the identified gaps. | 5% | 90-100 words |

To better understand the general composition of your research introduction, you may refer to the breakdown of this section below:

- Context Establishment and Introduction of Key Terms. In this subsection, you will articulate the background (historical, social, economic, psychological, etc.) of the study, including the ecosystem and the niche of your study interest. Furthermore, key terms found as variables in your study must be properly defined operationally and theoretically, if necessary. This comprises 20% of the introduction, or about 350-500 words.

- Related Literature and Studies. This is the subsection where you will criticize and integrate existing literature and studies to highlight the research gap that you intend to fill in. This comprises 25% of the introduction or about 450-600 words.

- Thesis statement. This part of the introduction can only be a paragraph or a couple of sentences, as this needs to be straightforward in relaying the identified research gap of the researchers. This comprises 5% of the introduction or about 90-100 words.

- Objectives or Research Questions. This subsection should outline the aims of the study, especially highlighting the inquiries that concern the relationship between the variables and how the research will progress to fill in the identified gaps. This comprises 5% of the introduction or about 90-100 words.

Theoretical and/or Conceptual Framework. These frameworks, when better assisted with a visual representation, guide the entire research process and provide a structure for understanding the relationship between the variables in the study. This comprises 10% of the introduction or about 180-200 words.

Struggling with your Research Paper?

Get your assignments done by real pros. Save your precious time and boost your marks with ease.

Elements of Good Research Writing Process– While Maintaining the Ideal Word Count!

- Clarity of Purpose . All types of writing, whether long or short, have its clarity of purpose as the heart of the text. In research, it is manifested through the inclusion of a research question or hypothesis. A good research paper does not repeat these elements without a purpose in mind. Though they can be emphasized throughout the development of the paper, the manner of doing it must be in a logical and purposeful way.

To guide you in writing process of doing so, you can ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the research question or hypothesis clearly stated?

- Does the introduction provide a clear overview of the purpose of the study?

- Does the purpose of the study repeat purposefully in the latter sections of the paper?

- Does the purpose of the study repeat logically in the latter sections of the paper?

2. Literature Review . When appending related literature and studies to your paper, the question must not revolve around whether you have supplied a lot of these pieces of information, making your article wordy and ideal. While the literature review adds a significant ‘chunk’ to your paper, with some paper formats even allotting a specific section for it, we must carefully consider what and how we can integrate them. It subsequently entails a critical analysis of a piece of literature or study and logically places it beside information that you desire to contest. As they say, a good literature review identifies knowledge gaps, highlights the author’s familiarity with the topic, and provides an overview of the research areas that show a disparity of agreement. In order to have these characteristics, you can ask yourself the following questions:

- Have I integrated relevant literature in my review?

- Have I placed it logically within a specific piece of information based on my presumption?

- Do they identify a concept or piece of information that is otherwise unknown to the field?

- Have I critically analyzed existing research to identify the research gap?

3. Logical Flow. Research will not be whole without its parts. Researchers must know how to tie everything together and ensure that each part is functional in itself and supplements with other parts. When dealing with a large body of text, the logical flow of the paper might be a considerable concern. Along with the confusion brought about by the wordiness and complexity of the topic, your readers might get lost because of incoherence and inconsistencies with the presentation of ideas, leading to them not reading your paper any further. Thus, while ensuring that you get the word count that you want, you might want to ask yourself these questions first:

- Does the introduction progress logically from the general background to the specific research question?

- Do the transition devices between sections and individual paragraphs of the body facilitate a smooth flow of ideas?

- Is there a clear hierarchy of ideas, with each paragraph contributing to the overall argument?

- Have I organized ideas in a way that makes the document easy to track?

- Have I pursued a logical sequence of presenting information?

4. Language Use and Style. Developing an academic language throughout your paper and maintaining a formal style of paper writing are all the more important in research writing process, and mind you, it can also help you increase your word count in a sustainable way! Incorporating this form of language and style into your paper entails more than just adding incoherent or overly manufactured words that may be viewed as fillers.

Strategies and known practices are said to hit multiple objectives without compromising the quality of the paper. You may expand your points by providing detailed explanations, introducing sufficient pieces of evidence that supports your claims, addressing counterargument through the presentation of related literature or studies, or clarifying complex concepts through chunking. To better understand these techniques, some of these questions might be helpful for you:

- Is the language clear and concise?

- Have I avoided unnecessary jargon or complex sentences or paragraphs?

- Have I avoided repetition or redundancy in the document?

- Have I expanded on key points by providing more detailed explanations and examples?

- Have I discussed nuances, variations, or exceptions to your results?

- Have I clarified some complex concepts or theories by chunking them into more detailed explanations?

How Long Should a Paragraph Be in a Research Paper?

For the research paper introduction section, a typical paragraph count will be 12-15, excluding the literature review section. Each subsection has 1-2 individual paragraphs. The mentioned section, on the other hand, can have paragraphs totaling 10-20. The conclusion section, on the other hand, is considered ideal if it has 5-7 paragraphs.

The paragraph count differs from one research type to another and even from one paper section to another. While it is worth deciding how long should a paragraph be in a research paper, it is more important to take note of the importance of ideas that should be included in each paragraph within a certain section. Take the review of the literature section as an example. The number of literature in the paper is said to be equal to the number of paragraphs allotted for the section. The reason lies in the uniformity of importance these pieces of literature hold, provided that they are closely associated with the research gap.

Do you feel like you need to pay for a research paper in hopes of finding a model article with the right paragraph count? Look no further, as Studyfy has its in-house research paper writing service that houses professionals and experts for your academic paper writing help. Its reasonable price– no deadline markup nor additional hidden charges– is tantamount to the expertise each writer has put into their work.

Did you like our inspiring Research Paper Guide?

For more help, tap into our pool of professional writers and get expert essay editing services!

How Long Should a Conclusion Be in a Research Paper?

A concluding section, then, must only comprise 5% of the total word count of the paper, translating to approximately 400 words. This measly allocation may put you into a flimsy situation, especially if you do not know how to manage your vocabulary well and you keep on adding filler words that can sacrifice the importance of this section. Ditch the nonsense and construct your conclusion in a concise yet enriching way.

In concluding a research paper, it is important to always synthesize the big chunks of information examined in the data analysis and discussion. As worn out as the reader may look after reaching this point, the conclusion must act as a “mellow point” for them, entrusting them only with important pointers of the study. Sometimes, the conclusion part of the paper, even though less wordy than its preceding sections, may be difficult to construct, as you still need to have a basis– a scaffold– to refer to, and synthesizing, just like analyzing and evaluating data, is just as hard and laborious.

Through its superb essay writing services , plus applying top-notch quality assurance to academic papers like research articles, Studyfy can help you achieve the best for last with an effective, meaningful, and content-rich conclusion. Your readers will not think twice about using your study as a model for their own works!

How Long is a Research Paper in terms of its Various Types?

As mentioned in the first part of the article, the word count of an academic paper is dependent on the type of research you wish to conduct. While the general word count has been given, we cannot deny the fact that this threshold is only an estimation. There might be a time when you are tasked to create a research article that is different from a standard IMRAD-structured (Introduction, Methodology, Results, Analysis, Discussion) research paper. You are in for a treat, as we will provide you with a cheat sheet for the word count of several types of write-ups in the realm of research:

Research Proposal

Specific Purpose/s: A preliminary outline that contains the research question, minimal literature review, methodology, and significance of the research undertaking.

"Word Count Range: 1500-3000 words"

Review Article

Specific Purpose/s: Review bodies of literature about an overarching topic or niche, analyze a particular section, synthesize according to certain themes, and identify knowledge gaps from the findings.

"Word Count Range: 5000-10,000 words"

Meta-Analysis

Specific Purpose/s: Involves the use of statistical analyses of multiple studies to provide a quantitative synthesis of the evidence.

"Word Count Range: 5000-15,000 words"

Specific Purpose/s: Presents an in-depth and intrusive analysis of a specific case, one which aims to illustrate a broader concept or novel phenomenon.

"Word Count Range: 1500-5000 words"

Conference Paper

Specific Purpose/s: Presents a brief introduction, salient research findings, and implications connected to a given theme by a conference or colloquium.

"Word Count Range: 2000-5000 words"

Dissertation

Specific Purpose/s: Regarded as a terminal scholarly requirement for doctorate students, this is an in-depth discussion of an otherwise original research finding, often written in chapters. It contributes significantly to the body of knowledge of a particular study of interest.

"Word Count Range: 50,000-100,000 words (depending on the institution)"

Are you contemplating buying research papers of different types? Studyfy got your back! Its roster of writers and editing experts leaves no space for errors, ensuring that both quality and quantity– that’s right: content and word count are not compromised. The variety of expertise within ensures that all research and scholarly works are delivered to your liking. Pay less– no hidden charges and markups while you enjoy the best quality of writing with Studyfy.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long is the introduction in a research paper.

AThe introduction takes up about 30-40% of the entire paper since the context and research background should be specified and further discussed. For a general academic paper with 4000 words, the introduction must be approximately 1500 words. You can do the math for the rest!

How long is a research paper, considering that there are many of them?

There is no one-size-fits-all guideline in determining the word count of a plethora of research papers in the world. Although there is an accepted word count range for each research type (as presented in the previous section), there are several factors that should likewise be considered in determining the word count: specific guidelines set by the institution you are working with, the complexity of the topic, audience, and depth of analysis.

Do I have to include all of the prescribed subsections of the introduction to increase the word count?

While the prescribed subsections have significant functions in the research paper introduction, some of them are not required to be included. The decisions depend on the type of research you wish to conduct and the external guidelines that you might need to follow. Some disciplines, such as social sciences, require a research article to have a theoretical framework, whereas others do not. Some research papers follow the standard IMRAD paper format that infuses the literature review section into the introduction, while the Germanic Thesis paper format, for example, regards the former as a separate section.

How do I increase my word count without compromising the quality of my research paper?

The dilemma of choosing quality over quantity has long been debunked: you do not have to choose in the first place. All you need is a set of writing strategies and techniques that will target those two birds using one stone. You may provide more detail to some ambiguous or novel terms. You can add additional works of literature to some concepts that promote abstraction. You may include examples or empirical pieces of evidence to create a more concrete representation of a concept or theory. Lastly, you may use subheadings to efficiently allocate word count for your chosen discussion topics.

Why is it important to track the word count of a research paper?

There are various reasons why we need to do it. Some institutions that publish scholarly journals follow certain guidelines in word count as one of the primary requirements. A specified limit enables researchers to allocate the number of words to several sections of their writing efficiently. Most institutions also use paper length as a predictor of publication cost. The longer the word count is, the costlier the publication will be. Lastly, reading engagement is affected by word count, as readers tend to shy away from reading an article that is long, boring, and insubstantial.

Can a writing service help me achieve my goals of writing within the right word count range?

Certainly! Studyfy offers several academic services, including writing services and research papers for sale . Understanding your various writing needs, writers can cater to the needed style, word count, formatting, and any other aspects so that you can have the best quality write-up without having to fear extra charges and big markups.

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

The Ideal Length of Research Papers: What’s Right for You?

Research papers are an essential part of the academic experience for many students, yet their ideal length is often contested. This article seeks to address this controversy by providing insight into what constitutes the appropriate and effective length for a research paper. A comprehensive exploration of guidelines from various sources, including university faculty members and leading industry professionals, will be presented in order to provide an informed opinion on this timely issue. Through careful analysis of data points such as word count limits, average document size requirements across institutions, formatting considerations based on style guides (e.g., MLA or APA), it can be determined which approach to research paper writing best serves both learners’ needs and instructors’ expectations. Ultimately, readers should expect a thorough examination that investigates every angle related to finding the “right” amount of content when constructing research papers that are academically sound while still being concisely expressed with precision clarity throughout each paragraph’s text flow.

1. Introduction: Understanding the Research Paper

2. the significance of length in a research paper, 3. traditional academic conventions for research papers, 4. alternatives to longer lengths: shorter formats and writing styles, 5. establishing your own ideal format or style of writing for your research paper, 6. considerations when setting an ideal length for your specific topic and audience, 7. conclusion: finding your optimal balance between brevity and depth.

Research papers are a form of communication between academics, and their purpose is to inform readers about the results of investigations into specific topics. The structure of research papers differs from that of other academic writings; they have an introduction, body sections for findings and discussion, as well as a conclusion.

- Length: Generally speaking, research paper length depends on the scope and complexity of the topic discussed but should usually be between 3-8 pages in total.

This type of writing requires critical thinking skills along with close attention to detail when it comes to data collection. It is essential that researchers take sufficient time outlining what information needs to be collected before beginning any investigation in order to ensure relevant results can be obtained. Additionally, having familiarity with various resources such as journal articles or books related to the topic being studied helps writers develop coherent arguments throughout their work.

The Impact of Length

A research paper’s length plays a critical role in the communication of its findings. Its length often helps determine how comprehensive, detailed and informative it is. Depending on the nature of the subject matter, longer papers may provide more information that can help readers understand complex concepts. In general, they are also seen as providing higher quality evidence since authors have more space to include robust argumentation for their conclusions. Therefore, when writing a research paper one should take into consideration not only what topics will be included but also how many pages are needed to effectively communicate these points.

In terms of determining an appropriate length for a particular project or academic field there is no definitive answer. Generally speaking however most undergraduate-level papers fall between 5–7 pages while graduate-level assignments tend to run 8–10 pages or even longer depending on the specific requirements set by supervisors and/or universities themselves.

The Basics of Academic Research Paper Writing

Research papers are a staple component in the academic world, requiring students to demonstrate their understanding and knowledge gained from courses. The traditional approach for producing an effective research paper is as follows:

- Develop a thesis statement which clearly outlines your argument.

- Identify and use credible sources that align with your argument.

These two components provide the foundation for any successful research paper. It should then be up to you, the writer, to create an effective structure that flows logically between ideas while expanding upon them sufficiently.

As research papers tend to require considerable effort and time, shorter formats can help get your point across quickly. There are a variety of alternative writing styles that you can employ when the length of your paper is restricted.

- Shorter Research Papers: These types of papers typically range from 1-3 pages in length. While there may be less space for arguments and analysis, they still provide enough room for students to effectively present their ideas without becoming bogged down by lengthy word counts or extraneous details.

- Essays: Essay writing provides an excellent opportunity to practice distilling complex information into smaller chunks while conveying key points succinctly. In general, essays should not exceed four pages (double spaced) depending on the course requirements.

Creating Your Own Format or Style of Writing Developing a style of writing that works best for your research paper can be an integral part of the success and impact it will have on readers. As such, you should spend ample time to find your individual format. When crafting your own personal style, some key factors to consider include clarity in language; cohesion among paragraphs and ideas; incorporating visuals effectively as possible (e.g., charts/graphs); properly citing sources; using simple but informative headings; introducing each main topic with a concise sentence or two, followed by bulleted points detailing its importance and implications; avoiding run-on sentences whenever applicable. Additionally, depending on where you are publishing your paper, there may also be specific formatting requirements dictated by publishers (this is especially common when submitting papers for publication). When it comes to length – while varying based on assignment type – general guidelines recommend that undergraduate research papers range from 3-7 pages in length while graduate-level assignments usually require 10+ page lengths.

When setting an ideal length for your topic and audience, it’s important to consider the purpose of your writing. Different types of documents have different lengths that are suitable in terms of scope and content. For example, a blog post can typically be shorter than a research paper or dissertation.

The other key factor is understanding who your target audience is – their expectations about document length will affect how long you should write. As a general rule, it helps to keep things concise by using short sentences and avoiding unnecessary detail where possible. Research papers often vary in length but they usually range from 8-10 pages double spaced; any longer may risk losing readers’ attention.

Achieving the Optimal Balance It can be challenging to determine exactly how much detail or brevity is appropriate for a research paper. The length of your paper will depend on the complexity and scope of your topic, as well as which formatting style you are using (e.g., MLA, APA). Generally speaking, though, most research papers should range from 5-15 pages long in order to adequately explore their topics while still keeping them concise and comprehensible.

- To balance depth with brevity:

When creating a research paper it is essential that you do not sacrifice substance for form; there must always be enough evidence provided within each section to support its assertions and claims. To ensure this without making your document too lengthy, try utilizing different writing techniques such as visual aids like diagrams or charts when presenting complex concepts. Additionally, focus on providing only key points rather than exhaustive details; strive for being succinct yet informative!

In conclusion, the length of research papers can vary greatly depending on a variety of factors. The most important thing is to understand your audience and purpose for writing and tailor your paper accordingly. As long as you are able to properly communicate all relevant information in an organized manner, then there should be no restriction on how long or short your paper needs to be; it all depends on what works best for you!

The “outdated sources” myth

- In-Text Citations

- Reference List

- Research and Publication

In this series, we will look at common APA Style misconceptions and debunk these myths one by one.

We often receive questions about whether sources must have been published within a certain time frame to be cited in a scholarly paper. Many writers incorrectly believe in the “outdated sources” myth, which is that sources must have been published recently, such as the last 5 to 10 years.

However, there is no timeliness requirement in APA Style guidelines (as defined in the Concise Guide to APA Style, Seventh Edition and Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, Seventh Edition ). Properly citing relevant sources is a key task for writers of any APA Style paper. You should “cite the work of those individuals whose ideas, theories, or research have directly influenced your work. The works you cite provide key background information, support or dispute your thesis, or offer critical definitions and data” (American Psychological Association, 2020, p. 253). We recommend citing reliable, primary sources with the most current information whenever possible.

What it means to be “timely” varies across fields or disciplines. Seminal research articles and/or foundational books can remain relevant for a long time and help establish the context for a given paper. For example, Albert Bandura’s Bobo doll experiment (Bandura et al., 1961) is often cited in contemporary social and child psychology articles. Remember, APA Style has no year-related cutoff.

As always, defer to your instructor’s guidelines when writing student papers. For example, your instructor may require sources be published within a certain timeframe for student papers. If so, follow that guideline for work in that class. Similarly, consider the discipline and audience for whom you are writing. For example, if you are submitting an article to a journal in a fast-developing field like neuroscience, more recent sources—if relevant and important for your readers to consider in the context of your paper—might make your article more competitive.

Now that we’ve debunked another myth, go forth APA Style writers, and cite noteworthy and relevant sources!

What myth should we debunk next? Leave a comment below.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 63 (3), 575–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045925

Related and recent

Comments are disabled due to your privacy settings. To re-enable, please adjust your cookie preferences.

APA Style Monthly

Subscribe to the APA Style Monthly newsletter to get tips, updates, and resources delivered directly to your inbox.

Welcome! Thank you for subscribing.

APA Style Guidelines

Browse APA Style writing guidelines by category

- Abbreviations

- Bias-Free Language

- Capitalization

- Italics and Quotation Marks

- Paper Format

- Punctuation

- Spelling and Hyphenation

- Tables and Figures

Full index of topics

- How to write a research paper

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

With proper planning, knowledge, and framework, completing a research paper can be a fulfilling and exciting experience.

Though it might initially sound slightly intimidating, this guide will help you embrace the challenge.

By documenting your findings, you can inspire others and make a difference in your field. Here's how you can make your research paper unique and comprehensive.

- What is a research paper?

Research papers allow you to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of a particular topic. These papers are usually lengthier and more detailed than typical essays, requiring deeper insight into the chosen topic.

To write a research paper, you must first choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to the field of study. Once you’ve selected your topic, gathering as many relevant resources as possible, including books, scholarly articles, credible websites, and other academic materials, is essential. You must then read and analyze these sources, summarizing their key points and identifying gaps in the current research.

You can formulate your ideas and opinions once you thoroughly understand the existing research. To get there might involve conducting original research, gathering data, or analyzing existing data sets. It could also involve presenting an original argument or interpretation of the existing research.

Writing a successful research paper involves presenting your findings clearly and engagingly, which might involve using charts, graphs, or other visual aids to present your data and using concise language to explain your findings. You must also ensure your paper adheres to relevant academic formatting guidelines, including proper citations and references.

Overall, writing a research paper requires a significant amount of time, effort, and attention to detail. However, it is also an enriching experience that allows you to delve deeply into a subject that interests you and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in your chosen field.

- How long should a research paper be?

Research papers are deep dives into a topic. Therefore, they tend to be longer pieces of work than essays or opinion pieces.

However, a suitable length depends on the complexity of the topic and your level of expertise. For instance, are you a first-year college student or an experienced professional?

Also, remember that the best research papers provide valuable information for the benefit of others. Therefore, the quality of information matters most, not necessarily the length. Being concise is valuable.

Following these best practice steps will help keep your process simple and productive:

1. Gaining a deep understanding of any expectations

Before diving into your intended topic or beginning the research phase, take some time to orient yourself. Suppose there’s a specific topic assigned to you. In that case, it’s essential to deeply understand the question and organize your planning and approach in response. Pay attention to the key requirements and ensure you align your writing accordingly.

This preparation step entails

Deeply understanding the task or assignment

Being clear about the expected format and length

Familiarizing yourself with the citation and referencing requirements

Understanding any defined limits for your research contribution

Where applicable, speaking to your professor or research supervisor for further clarification

2. Choose your research topic

Select a research topic that aligns with both your interests and available resources. Ideally, focus on a field where you possess significant experience and analytical skills. In crafting your research paper, it's crucial to go beyond summarizing existing data and contribute fresh insights to the chosen area.

Consider narrowing your focus to a specific aspect of the topic. For example, if exploring the link between technology and mental health, delve into how social media use during the pandemic impacts the well-being of college students. Conducting interviews and surveys with students could provide firsthand data and unique perspectives, adding substantial value to the existing knowledge.

When finalizing your topic, adhere to legal and ethical norms in the relevant area (this ensures the integrity of your research, protects participants' rights, upholds intellectual property standards, and ensures transparency and accountability). Following these principles not only maintains the credibility of your work but also builds trust within your academic or professional community.

For instance, in writing about medical research, consider legal and ethical norms , including patient confidentiality laws and informed consent requirements. Similarly, if analyzing user data on social media platforms, be mindful of data privacy regulations, ensuring compliance with laws governing personal information collection and use. Aligning with legal and ethical standards not only avoids potential issues but also underscores the responsible conduct of your research.

3. Gather preliminary research

Once you’ve landed on your topic, it’s time to explore it further. You’ll want to discover more about available resources and existing research relevant to your assignment at this stage.

This exploratory phase is vital as you may discover issues with your original idea or realize you have insufficient resources to explore the topic effectively. This key bit of groundwork allows you to redirect your research topic in a different, more feasible, or more relevant direction if necessary.

Spending ample time at this stage ensures you gather everything you need, learn as much as you can about the topic, and discover gaps where the topic has yet to be sufficiently covered, offering an opportunity to research it further.

4. Define your research question

To produce a well-structured and focused paper, it is imperative to formulate a clear and precise research question that will guide your work. Your research question must be informed by the existing literature and tailored to the scope and objectives of your project. By refining your focus, you can produce a thoughtful and engaging paper that effectively communicates your ideas to your readers.

5. Write a thesis statement

A thesis statement is a one-to-two-sentence summary of your research paper's main argument or direction. It serves as an overall guide to summarize the overall intent of the research paper for you and anyone wanting to know more about the research.

A strong thesis statement is:

Concise and clear: Explain your case in simple sentences (avoid covering multiple ideas). It might help to think of this section as an elevator pitch.

Specific: Ensure that there is no ambiguity in your statement and that your summary covers the points argued in the paper.

Debatable: A thesis statement puts forward a specific argument––it is not merely a statement but a debatable point that can be analyzed and discussed.

Here are three thesis statement examples from different disciplines:

Psychology thesis example: "We're studying adults aged 25-40 to see if taking short breaks for mindfulness can help with stress. Our goal is to find practical ways to manage anxiety better."

Environmental science thesis example: "This research paper looks into how having more city parks might make the air cleaner and keep people healthier. I want to find out if more green spaces means breathing fewer carcinogens in big cities."

UX research thesis example: "This study focuses on improving mobile banking for older adults using ethnographic research, eye-tracking analysis, and interactive prototyping. We investigate the usefulness of eye-tracking analysis with older individuals, aiming to spark debate and offer fresh perspectives on UX design and digital inclusivity for the aging population."

6. Conduct in-depth research

A research paper doesn’t just include research that you’ve uncovered from other papers and studies but your fresh insights, too. You will seek to become an expert on your topic––understanding the nuances in the current leading theories. You will analyze existing research and add your thinking and discoveries. It's crucial to conduct well-designed research that is rigorous, robust, and based on reliable sources. Suppose a research paper lacks evidence or is biased. In that case, it won't benefit the academic community or the general public. Therefore, examining the topic thoroughly and furthering its understanding through high-quality research is essential. That usually means conducting new research. Depending on the area under investigation, you may conduct surveys, interviews, diary studies , or observational research to uncover new insights or bolster current claims.

7. Determine supporting evidence

Not every piece of research you’ve discovered will be relevant to your research paper. It’s important to categorize the most meaningful evidence to include alongside your discoveries. It's important to include evidence that doesn't support your claims to avoid exclusion bias and ensure a fair research paper.

8. Write a research paper outline

Before diving in and writing the whole paper, start with an outline. It will help you to see if more research is needed, and it will provide a framework by which to write a more compelling paper. Your supervisor may even request an outline to approve before beginning to write the first draft of the full paper. An outline will include your topic, thesis statement, key headings, short summaries of the research, and your arguments.

9. Write your first draft

Once you feel confident about your outline and sources, it’s time to write your first draft. While penning a long piece of content can be intimidating, if you’ve laid the groundwork, you will have a structure to help you move steadily through each section. To keep up motivation and inspiration, it’s often best to keep the pace quick. Stopping for long periods can interrupt your flow and make jumping back in harder than writing when things are fresh in your mind.

10. Cite your sources correctly

It's always a good practice to give credit where it's due, and the same goes for citing any works that have influenced your paper. Building your arguments on credible references adds value and authenticity to your research. In the formatting guidelines section, you’ll find an overview of different citation styles (MLA, CMOS, or APA), which will help you meet any publishing or academic requirements and strengthen your paper's credibility. It is essential to follow the guidelines provided by your school or the publication you are submitting to ensure the accuracy and relevance of your citations.

11. Ensure your work is original

It is crucial to ensure the originality of your paper, as plagiarism can lead to serious consequences. To avoid plagiarism, you should use proper paraphrasing and quoting techniques. Paraphrasing is rewriting a text in your own words while maintaining the original meaning. Quoting involves directly citing the source. Giving credit to the original author or source is essential whenever you borrow their ideas or words. You can also use plagiarism detection tools such as Scribbr or Grammarly to check the originality of your paper. These tools compare your draft writing to a vast database of online sources. If you find any accidental plagiarism, you should correct it immediately by rephrasing or citing the source.

12. Revise, edit, and proofread

One of the essential qualities of excellent writers is their ability to understand the importance of editing and proofreading. Even though it's tempting to call it a day once you've finished your writing, editing your work can significantly improve its quality. It's natural to overlook the weaker areas when you've just finished writing a paper. Therefore, it's best to take a break of a day or two, or even up to a week, to refresh your mind. This way, you can return to your work with a new perspective. After some breathing room, you can spot any inconsistencies, spelling and grammar errors, typos, or missing citations and correct them.

- The best research paper format

The format of your research paper should align with the requirements set forth by your college, school, or target publication.

There is no one “best” format, per se. Depending on the stated requirements, you may need to include the following elements:

Title page: The title page of a research paper typically includes the title, author's name, and institutional affiliation and may include additional information such as a course name or instructor's name.

Table of contents: Include a table of contents to make it easy for readers to find specific sections of your paper.

Abstract: The abstract is a summary of the purpose of the paper.

Methods : In this section, describe the research methods used. This may include collecting data , conducting interviews, or doing field research .

Results: Summarize the conclusions you drew from your research in this section.

Discussion: In this section, discuss the implications of your research . Be sure to mention any significant limitations to your approach and suggest areas for further research.

Tables, charts, and illustrations: Use tables, charts, and illustrations to help convey your research findings and make them easier to understand.

Works cited or reference page: Include a works cited or reference page to give credit to the sources that you used to conduct your research.

Bibliography: Provide a list of all the sources you consulted while conducting your research.

Dedication and acknowledgments : Optionally, you may include a dedication and acknowledgments section to thank individuals who helped you with your research.

- General style and formatting guidelines

Formatting your research paper means you can submit it to your college, journal, or other publications in compliance with their criteria.

Research papers tend to follow the American Psychological Association (APA), Modern Language Association (MLA), or Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) guidelines.

Here’s how each style guide is typically used:

Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS):

CMOS is a versatile style guide used for various types of writing. It's known for its flexibility and use in the humanities. CMOS provides guidelines for citations, formatting, and overall writing style. It allows for both footnotes and in-text citations, giving writers options based on their preferences or publication requirements.

American Psychological Association (APA):

APA is common in the social sciences. It’s hailed for its clarity and emphasis on precision. It has specific rules for citing sources, creating references, and formatting papers. APA style uses in-text citations with an accompanying reference list. It's designed to convey information efficiently and is widely used in academic and scientific writing.

Modern Language Association (MLA):

MLA is widely used in the humanities, especially literature and language studies. It emphasizes the author-page format for in-text citations and provides guidelines for creating a "Works Cited" page. MLA is known for its focus on the author's name and the literary works cited. It’s frequently used in disciplines that prioritize literary analysis and critical thinking.

To confirm you're using the latest style guide, check the official website or publisher's site for updates, consult academic resources, and verify the guide's publication date. Online platforms and educational resources may also provide summaries and alerts about any revisions or additions to the style guide.

Citing sources

When working on your research paper, it's important to cite the sources you used properly. Your citation style will guide you through this process. Generally, there are three parts to citing sources in your research paper:

First, provide a brief citation in the body of your essay. This is also known as a parenthetical or in-text citation.

Second, include a full citation in the Reference list at the end of your paper. Different types of citations include in-text citations, footnotes, and reference lists.

In-text citations include the author's surname and the date of the citation.

Footnotes appear at the bottom of each page of your research paper. They may also be summarized within a reference list at the end of the paper.

A reference list includes all of the research used within the paper at the end of the document. It should include the author, date, paper title, and publisher listed in the order that aligns with your citation style.

10 research paper writing tips:

Following some best practices is essential to writing a research paper that contributes to your field of study and creates a positive impact.

These tactics will help you structure your argument effectively and ensure your work benefits others:

Clear and precise language: Ensure your language is unambiguous. Use academic language appropriately, but keep it simple. Also, provide clear takeaways for your audience.

Effective idea separation: Organize the vast amount of information and sources in your paper with paragraphs and titles. Create easily digestible sections for your readers to navigate through.

Compelling intro: Craft an engaging introduction that captures your reader's interest. Hook your audience and motivate them to continue reading.

Thorough revision and editing: Take the time to review and edit your paper comprehensively. Use tools like Grammarly to detect and correct small, overlooked errors.

Thesis precision: Develop a clear and concise thesis statement that guides your paper. Ensure that your thesis aligns with your research's overall purpose and contribution.

Logical flow of ideas: Maintain a logical progression throughout the paper. Use transitions effectively to connect different sections and maintain coherence.

Critical evaluation of sources: Evaluate and critically assess the relevance and reliability of your sources. Ensure that your research is based on credible and up-to-date information.

Thematic consistency: Maintain a consistent theme throughout the paper. Ensure that all sections contribute cohesively to the overall argument.

Relevant supporting evidence: Provide concise and relevant evidence to support your arguments. Avoid unnecessary details that may distract from the main points.

Embrace counterarguments: Acknowledge and address opposing views to strengthen your position. Show that you have considered alternative arguments in your field.

7 research tips

If you want your paper to not only be well-written but also contribute to the progress of human knowledge, consider these tips to take your paper to the next level:

Selecting the appropriate topic: The topic you select should align with your area of expertise, comply with the requirements of your project, and have sufficient resources for a comprehensive investigation.

Use academic databases: Academic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and JSTOR offer a wealth of research papers that can help you discover everything you need to know about your chosen topic.

Critically evaluate sources: It is important not to accept research findings at face value. Instead, it is crucial to critically analyze the information to avoid jumping to conclusions or overlooking important details. A well-written research paper requires a critical analysis with thorough reasoning to support claims.

Diversify your sources: Expand your research horizons by exploring a variety of sources beyond the standard databases. Utilize books, conference proceedings, and interviews to gather diverse perspectives and enrich your understanding of the topic.

Take detailed notes: Detailed note-taking is crucial during research and can help you form the outline and body of your paper.

Stay up on trends: Keep abreast of the latest developments in your field by regularly checking for recent publications. Subscribe to newsletters, follow relevant journals, and attend conferences to stay informed about emerging trends and advancements.

Engage in peer review: Seek feedback from peers or mentors to ensure the rigor and validity of your research . Peer review helps identify potential weaknesses in your methodology and strengthens the overall credibility of your findings.

- The real-world impact of research papers

Writing a research paper is more than an academic or business exercise. The experience provides an opportunity to explore a subject in-depth, broaden one's understanding, and arrive at meaningful conclusions. With careful planning, dedication, and hard work, writing a research paper can be a fulfilling and enriching experience contributing to advancing knowledge.

How do I publish my research paper?

Many academics wish to publish their research papers. While challenging, your paper might get traction if it covers new and well-written information. To publish your research paper, find a target publication, thoroughly read their guidelines, format your paper accordingly, and send it to them per their instructions. You may need to include a cover letter, too. After submission, your paper may be peer-reviewed by experts to assess its legitimacy, quality, originality, and methodology. Following review, you will be informed by the publication whether they have accepted or rejected your paper.

What is a good opening sentence for a research paper?

Beginning your research paper with a compelling introduction can ensure readers are interested in going further. A relevant quote, a compelling statistic, or a bold argument can start the paper and hook your reader. Remember, though, that the most important aspect of a research paper is the quality of the information––not necessarily your ability to storytell, so ensure anything you write aligns with your goals.

Research paper vs. a research proposal—what’s the difference?

While some may confuse research papers and proposals, they are different documents.

A research proposal comes before a research paper. It is a detailed document that outlines an intended area of exploration. It includes the research topic, methodology, timeline, sources, and potential conclusions. Research proposals are often required when seeking approval to conduct research.

A research paper is a summary of research findings. A research paper follows a structured format to present those findings and construct an argument or conclusion.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 15 January 2024

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 7 March 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

- 10 research paper

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.18(6); 2022 Jun

Ten simple rules for good research practice

Simon schwab.

1 Center for Reproducible Science, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

2 Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Prevention Institute, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Perrine Janiaud

3 Department of Clinical Research, University Hospital Basel, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Michael Dayan

4 Human Neuroscience Platform, Fondation Campus Biotech Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

Valentin Amrhein

5 Department of Environmental Sciences, Zoology, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Radoslaw Panczak

6 Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

Patricia M. Palagi

7 SIB Training Group, SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Lausanne, Switzerland

Lars G. Hemkens

8 Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford (METRICS), Stanford University, Stanford, California, United States of America

9 Meta-Research Innovation Center Berlin (METRIC-B), Berlin Institute of Health, Berlin, Germany

Meike Ramon

10 Applied Face Cognition Lab, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

Nicolas Rothen

11 Faculty of Psychology, UniDistance Suisse, Brig, Switzerland

Stephen Senn

12 Statistical Consultant, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Leonhard Held

This is a PLOS Computational Biology Methods paper.

Introduction

The lack of research reproducibility has caused growing concern across various scientific fields [ 1 – 5 ]. Today, there is widespread agreement, within and outside academia, that scientific research is suffering from a reproducibility crisis [ 6 , 7 ]. Researchers reach different conclusions—even when the same data have been processed—simply due to varied analytical procedures [ 8 , 9 ]. As we continue to recognize this problematic situation, some major causes of irreproducible research have been identified. This, in turn, provides the foundation for improvement by identifying and advocating for good research practices (GRPs). Indeed, powerful solutions are available, for example, preregistration of study protocols and statistical analysis plans, sharing of data and analysis code, and adherence to reporting guidelines. Although these and other best practices may facilitate reproducible research and increase trust in science, it remains the responsibility of researchers themselves to actively integrate them into their everyday research practices.

Contrary to ubiquitous specialized training, cross-disciplinary courses focusing on best practices to enhance the quality of research are lacking at universities and are urgently needed. The intersections between disciplines offer a space for peer evaluation, mutual learning, and sharing of best practices. In medical research, interdisciplinary work is inevitable. For example, conducting clinical trials requires experts with diverse backgrounds, including clinical medicine, pharmacology, biostatistics, evidence synthesis, nursing, and implementation science. Bringing researchers with diverse backgrounds and levels of experience together to exchange knowledge and learn about problems and solutions adds value and improves the quality of research.

The present selection of rules was based on our experiences with teaching GRP courses at the University of Zurich, our course participants’ feedback, and the views of a cross-disciplinary group of experts from within the Swiss Reproducibility Network ( www.swissrn.org ). The list is neither exhaustive, nor does it aim to address and systematically summarize the wide spectrum of issues including research ethics and legal aspects (e.g., related to misconduct, conflicts of interests, and scientific integrity). Instead, we focused on practical advice at the different stages of everyday research: from planning and execution to reporting of research. For a more comprehensive overview on GRPs, we point to the United Kingdom’s Medical Research Council’s guidelines [ 10 ] and the Swedish Research Council’s report [ 11 ]. While the discussion of the rules may predominantly focus on clinical research, much applies, in principle, to basic biomedical research and research in other domains as well.

The 10 proposed rules can serve multiple purposes: an introduction for researchers to relevant concepts to improve research quality, a primer for early-career researchers who participate in our GRP courses, or a starting point for lecturers who plan a GRP course at their own institutions. The 10 rules are grouped according to planning (5 rules), execution (3 rules), and reporting of research (2 rules); see Fig 1 . These principles can (and should) be implemented as a habit in everyday research, just like toothbrushing.

GRP, good research practices.

Research planning

Rule 1: specify your research question.

Coming up with a research question is not always simple and may take time. A successful study requires a narrow and clear research question. In evidence-based research, prior studies are assessed in a systematic and transparent way to identify a research gap for a new study that answers a question that matters [ 12 ]. Papers that provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research in the field are particularly helpful—for example, systematic reviews. Perspective papers may also be useful, for example, there is a paper with the title “SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: The most important research questions.” However, a systematic assessment of research gaps deserves more attention than opinion-based publications.

In the next step, a vague research question should be further developed and refined. In clinical research and evidence-based medicine, there is an approach called population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and time frame (PICOT) with a set of criteria that can help framing a research question [ 13 ]. From a well-developed research question, subsequent steps will follow, which may include the exact definition of the population, the outcome, the data to be collected, and the sample size that is required. It may be useful to find out if other researchers find the idea interesting as well and whether it might promise a valuable contribution to the field. However, actively involving the public or the patients can be a more effective way to determine what research questions matter.

The level of details in a research question also depends on whether the planned research is confirmatory or exploratory. In contrast to confirmatory research, exploratory research does not require a well-defined hypothesis from the start. Some examples of exploratory experiments are those based on omics and multi-omics experiments (genomics, bulk RNA-Seq, single-cell, etc.) in systems biology and connectomics and whole-brain analyses in brain imaging. Both exploration and confirmation are needed in science, and it is helpful to understand their strengths and limitations [ 14 , 15 ].

Rule 2: Write and register a study protocol

In clinical research, registration of clinical trials has become a standard since the late 1990 and is now a legal requirement in many countries. Such studies require a study protocol to be registered, for example, with ClinicalTrials.gov, the European Clinical Trials Register, or the World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. Similar effort has been implemented for registration of systematic reviews (PROSPERO). Study registration has also been proposed for observational studies [ 16 ] and more recently in preclinical animal research [ 17 ] and is now being advocated across disciplines under the term “preregistration” [ 18 , 19 ].

Study protocols typically document at minimum the research question and hypothesis, a description of the population, the targeted sample size, the inclusion/exclusion criteria, the study design, the data collection, the data processing and transformation, and the planned statistical analyses. The registration of study protocols reduces publication bias and hindsight bias and can safeguard honest research and minimize waste of research [ 20 – 22 ]. Registration ensures that studies can be scrutinized by comparing the reported research with what was actually planned and written in the protocol, and any discrepancies may indicate serious problems (e.g., outcome switching).

Note that registration does not mean that researchers have no flexibility to adapt the plan as needed. Indeed, new or more appropriate procedures may become available or known only after registration of a study. Therefore, a more detailed statistical analysis plan can be amended to the protocol before the data are observed or unblinded [ 23 , 24 ]. Likewise, registration does not exclude the possibility to conduct exploratory data analyses; however, they must be clearly reported as such.

To go even further, registered reports are a novel article type that incentivize high-quality research—irrespective of the ultimate study outcome [ 25 , 26 ]. With registered reports, peer-reviewers decide before anyone knows the results of the study, and they have a more active role in being able to influence the design and analysis of the study. Journals from various disciplines increasingly support registered reports [ 27 ].

Naturally, preregistration and registered reports also have their limitations and may not be appropriate in a purely hypothesis-generating (explorative) framework. Reports of exploratory studies should indeed not be molded into a confirmatory framework; appropriate rigorous reporting alternatives have been suggested and start to become implemented [ 28 , 29 ].

Rule 3: Justify your sample size

Early-career researchers in our GRP courses often identify sample size as an issue in their research. For example, they say that they work with a low number of samples due to slow growth of cells, or they have a limited number of patient tumor samples due to a rare disease. But if your sample size is too low, your study has a high risk of providing a false negative result (type II error). In other words, you are unlikely to find an effect even if there truly was an effect.

Unfortunately, there is more bad news with small studies. When an effect from a small study was selected for drawing conclusions because it was statistically significant, low power increases the probability that an effect size is overestimated [ 30 , 31 ]. The reason is that with low power, studies that due to sampling variation find larger (overestimated) effects are much more likely to be statistically significant than those that happen to find smaller (more realistic) effects [ 30 , 32 , 33 ]. Thus, in such situations, effect sizes are often overestimated. For the phenomenon that small studies often report more extreme results (in meta-analyses), the term “small-study effect” was introduced [ 34 ]. In any case, an underpowered study is a problematic study, no matter the outcome.

In conclusion, small sample sizes can undermine research, but when is a study too small? For one study, a total of 50 patients may be fine, but for another, 1,000 patients may be required. How large a study needs to be designed requires an appropriate sample size calculation. Appropriate sample size calculation ensures that enough data are collected to ensure sufficient statistical power (the probability to reject the null hypothesis when it is in fact false).

Low-powered studies can be avoided by performing a sample size calculation to find out the required sample size of the study. This requires specifying a primary outcome variable and the magnitude of effect you are interested in (among some other factors); in clinical research, this is often the minimal clinically relevant difference. The statistical power is often set at 80% or larger. A comprehensive list of packages for sample size calculation are available [ 35 ], among them the R package “pwr” [ 36 ]. There are also many online calculators available, for example, the University of Zurich’s “SampleSizeR” [ 37 ].

A worthwhile alternative for planning the sample size that puts less emphasis on null hypothesis testing is based on the desired precision of the study; for example, one can calculate the sample size that is necessary to obtain a desired width of a confidence interval for the targeted effect [ 38 – 40 ]. A general framework to sample size justification beyond a calculation-only approach has been proposed [ 41 ]. It is also worth mentioning that some study types have other requirements or need specific methods. In diagnostic testing, one would need to determine the anticipated minimal sensitivity or specificity; in prognostic research, the number of parameters that can be used to fit a prediction model given a fixed sample size should be specified. Designs can also be so complex that a simulation (Monte Carlo method) may be required.

Sample size calculations should be done under different assumptions, and the largest estimated sample size is often the safer bet than a best-case scenario. The calculated sample size should further be adjusted to allow for possible missing data. Due to the complexity of accurately calculating sample size, researchers should strongly consider consulting a statistician early in the study design process.

Rule 4: Write a data management plan

In 2020, 2 Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) papers in leading medical journals were retracted after major concerns about the data were raised [ 42 ]. Today, raw data are more often recognized as a key outcome of research along with the paper. Therefore, it is important to develop a strategy for the life cycle of data, including suitable infrastructure for long-term storage.

The data life cycle is described in a data management plan: a document that describes what data will be collected and how the data will be organized, stored, handled, and protected during and after the end of the research project. Several funders require a data management plan in grant submissions, and publishers like PLOS encourage authors to do so as well. The Wellcome Trust provides guidance in the development of a data management plan, including real examples from neuroimaging, genomics, and social sciences [ 43 ]. However, projects do not always allocate funding and resources to the actual implementation of the data management plan.

The Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) data principles promote maximal use of data and enable machines to access and reuse data with minimal human intervention [ 44 ]. FAIR principles require the data to be retained, preserved, and shared preferably with an immutable unique identifier and a clear usage license. Appropriate metadata will help other researchers (or machines) to discover, process, and understand the data. However, requesting researchers to fully comply with the FAIR data principles in every detail is an ambitious goal.

Multidisciplinary data repositories that support FAIR are, for example, Dryad (datadryad.org https://datadryad.org/ ), EUDAT ( www.eudat.eu ), OSF (osf.io https://osf.io/ ), and Zenodo (zenodo.org https://zenodo.org/ ). A number of institutional and field-specific repositories may also be suitable. However, sometimes, authors may not be able to make their data publicly available for legal or ethical reasons. In such cases, a data user agreement can indicate the conditions required to access the data. Journals highlight what are acceptable and what are unacceptable data access restrictions and often require a data availability statement.

Organizing the study artifacts in a structured way greatly facilitates the reuse of data and code within and outside the lab, enhancing collaborations and maximizing the research investment. Support and courses for data management plans are sometimes available at universities. Another 10 simple rules paper for creating a good data management plan is dedicated to this topic [ 45 ].

Rule 5: Reduce bias

Bias is a distorted view in favor of or against a particular idea. In statistics, bias is a systematic deviation of a statistical estimate from the (true) quantity it estimates. Bias can invalidate our conclusions, and the more bias there is, the less valid they are. For example, in clinical studies, bias may mislead us into reaching a causal conclusion that the difference in the outcomes was due to the intervention or the exposure. This is a big concern, and, therefore, the risk of bias is assessed in clinical trials [ 46 ] as well as in observational studies [ 47 , 48 ].

There are many different forms of bias that can occur in a study, and they may overlap (e.g., allocation bias and confounding bias) [ 49 ]. Bias can occur at different stages, for example, immortal time bias in the design of the study, information bias in the execution of the study, and publication bias in the reporting of research. Understanding bias allows us researchers to remain vigilant of potential sources of bias when peer-reviewing and designing own studies. We summarized some common types of bias and some preventive steps in Table 1 , but many other forms of bias exist; for a comprehensive overview, see the Oxford University’s Catalogue of Bias [ 50 ].

| Name | Explanation | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Allocation bias | Systematic difference in the assignment of participants to the treatment and control group in a clinical trial. For example, the investigator knows or can predict which intervention the next eligible patient is supposed to receive due to poorly concealed randomization. | - Randomization with allocation concealment |

| Attrition bias | Attrition occurs when participants leave during a study that aims to explore the effect of continuous exposure (dropouts or withdrawal). For example, more dropouts of patients randomized to an aggressive cancer treatment. | - Good investigator–patient communication - Accessibility of clinics - Incentives to continue |

| Confounding bias | An artificial association between an exposure and an outcome because another variable is related to both the exposure and outcome. For example, lung cancer risk in coffee drinkers is evaluated, ignoring smoking status (smoking is associated with both coffee drinking and cancer). A challenge is that many confounders are unknown and/or not measured. | - Randomization (can address unmeasured confounders) When randomization is not possible: - Restriction to one level of the confounder - Matching on the levels of the confounder - Stratification and analysis within strata - Propensity score matching |

| Immortal time bias | Survival beyond a certain time point is necessary in order to be exposed (participants are “immortal” in that time period). For example, discharged patients are analyzed but were included in the treatment group only if they filled a prescription for a drug 90 days after discharge from hospital. | - Group assignment at time zero - Time-dependent analysis may be used |

| Information bias | Bias that arises from systematic differences in the collection, recall, recording, or handling of information. For example, blood pressure in the treatment arm is measured in the morning and for the control arm in the evening. | - Standardized data collection - Data collection independent from exposure or outcome (e.g., by blinding of intervention status/exposure) - Use of objective measurements |

| Publication bias | Occurs when only studies with a positive or negative result are published. Affects meta-analyses from systematic reviews and harms evidence-based medicine | - Writing a study protocol and preregistration - Publishing study protocol or registered report - Following reporting guidelines |

For a comprehensive collection, see catalogofbias.org .

Here are some noteworthy examples of study bias from the literature: An example of information bias was observed when in 1998 an alleged association between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism was reported. Recall bias (a subtype of information bias) emerged when parents of autistic children recalled the onset of autism after an MMR vaccination more often than parents of similar children who were diagnosed prior to the media coverage of that controversial and meanwhile retracted study [ 51 ]. A study from 2001 showed better survival for academy award-winning actors, but this was due to immortal time bias that favors the treatment or exposure group [ 52 , 53 ]. A study systematically investigated self-reports about musculoskeletal symptoms and found the presence of information bias. The reason was that participants with little computer-time overestimated, and participants with a lot of computer-time spent underestimated their computer usage [ 54 ].

Information bias can be mitigated by using objective rather than subjective measurements. Standardized operating procedures (SOP) and electronic lab notebooks additionally help to follow well-designed protocols for data collection and handling [ 55 ]. Despite the failure to mitigate bias in studies, complete descriptions of data and methods can at least allow the assessment of risk of bias.

Research execution

Rule 6: avoid questionable research practices.

Questionable research practices (QRPs) can lead to exaggerated findings and false conclusions and thus lead to irreproducible research. Often, QRPs are used with no bad intentions. This becomes evident when methods sections explicitly describe such procedures, for example, to increase the number of samples until statistical significance is reached that supports the hypothesis. Therefore, it is important that researchers know about QRPs in order to recognize and avoid them.

Several questionable QRPs have been named [ 56 , 57 ]. Among them are low statistical power, pseudoreplication, repeated inspection of data, p -hacking [ 58 ], selective reporting, and hypothesizing after the results are known (HARKing).