Evidence and practice: a review of vignettes in qualitative research

Affiliations.

- 1 Institute of Health Professions, University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, England.

- 2 Keele University, Keele, England.

- PMID: 34041889

- DOI: 10.7748/nr.2021.e1787

Background: Developing and working through a PhD research study requires tenacity, continuous development and application of knowledge. It is paramount when researching sensitive topics to consider carefully the construction of tools for collecting data, to ensure the study is ethically robust and explicitly addresses the research question.

Aim: To explore how novice researchers can develop insight into aspects of the research process by developing vignettes as a research tool.

Discussion: This article focuses on the use of vignettes to collect data as part of a qualitative PhD study investigating making decisions in the best interests of and on behalf of people with advanced dementia. Developing vignettes is a purposeful, conscious process. It is equally important to ensure that vignettes are derived from literature, have an evidence base, are carefully constructed and peer-reviewed, and are suitable to achieve the research's aims.

Conclusion: Using and analysing a vignette enables novice researchers to make sense of aspects of the qualitative research process and engage with it to appreciate terminology.

Implications for practice: Vignettes can provide an effective platform for discussion when researching topics where participants may be reluctant to share sensitive real-life experiences.

Keywords: data collection; instrument design; interviews; methodology; narrative; qualitative research; research; research methods; study design.

©2021 RCN Publishing Company Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be copied, transmitted or recorded in any way, in whole or part, without prior permission of the publishers.

Publication types

- Decision Making*

- Qualitative Research

- Research Personnel*

Social Research Update is published quarterly by the Department of Sociology, University of Surrey, Guildford GU2 7XH, England. Subscriptions for the hardcopy version are free to researchers with addresses in the UK. Apply by email to [email protected] .

Emma Renold has just completed her PhD on an ethnographic exploration into the construction of children’s gender and sexual identities. She is employed by the NSPCC as a research assistant working on the ‘violence in children’s homes’ project and is writing a literature review on the sexual exploitation of children.

Social Research Update is published by:

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 12, Issue 1

- Development and use of research vignettes to collect qualitative data from healthcare professionals: a scoping review

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1798-5681 Dominique Tremblay 1 , 2 ,

- Annie Turcotte 1 , 2 ,

- Nassera Touati 3 ,

- Thomas G Poder 4 , 5 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2137-6560 Kelley Kilpatrick 6 , 7 ,

- Karine Bilodeau 8 ,

- Mathieu Roy 9 ,

- Patrick O Richard 10 ,

- Sylvie Lessard 2 ,

- Émilie Giordano 2

- 1 School of Nursing , Université de Sherbrooke , Longueuil , Quebec , Canada

- 2 Centre de recherche Charles-Le Moyne , Longueuil , Quebec , Canada

- 3 École Nationale d’Administration Publique , Montreal , Quebec , Canada

- 4 School of Public Health , Université de Montréal , Montreal , Quebec , Canada

- 5 Centre de Recherche de l’Institut Universitaire en Santé Mentale de Montréal, Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux de l’Est-de-l’Île-de-Montréal , Montreal , Quebec , Canada

- 6 Ingram School of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine , McGill University , Montreal , Quebec , Canada

- 7 Susan E. French Chair in Nursing Research and Innovative Practice , Montreal , Quebec , Canada

- 8 Faculty of Nursing , Université de Montréal , Montreal , Quebec , Canada

- 9 Department of Family Medicine and Emergency Medicine , Université de Sherbrooke , Sherbrooke , Quebec , Canada

- 10 Department of Surgery , Université de Sherbrooke , Sherbrooke , Quebec , Canada

- Correspondence to Professor Dominique Tremblay; dominique.tremblay2{at}usherbrooke.ca

Objectives To clarify the definition of vignette-based methodology in qualitative research and to identify key elements underpinning its development and utilisation in qualitative empirical studies involving healthcare professionals.

Design Scoping review according to the Joanna Briggs Institute framework and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines.

Data sources Electronic databases: Academic Search Complete, CINAHL Plus, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and SocINDEX (January 2000–December 2020).

Eligibility criteria Empirical studies in English or French with a qualitative design including an explicit methodological description of the development and/or use of vignettes to collect qualitative data from healthcare professionals. Titles and abstracts were screened, and full text was reviewed by pairs of researchers according to inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Data extraction and synthesis Data extraction included study characteristics, definition, development and utilisation of a vignette, as well as strengths, limitations and recommendations from authors of the included articles. Systematic qualitative thematic analysis was performed, followed by data matrices to display the findings according to the scoping review questions.

Results Ten articles were included. An explicit definition of vignettes was provided in only half the studies. Variations of the development process (steps, expert consultation and pretesting), data collection and analysis demonstrate opportunities for improvement in rigour and transparency of the whole research process. Most studies failed to address quality criteria of the wider qualitative design and to discuss study limitations.

Conclusions Vignette-based studies in qualitative research appear promising to deepen our understanding of sensitive and challenging situations lived by healthcare professionals. However, vignettes require conceptual clarification and robust methodological guidance so that researchers can systematically plan their study. Focusing on quality criteria of qualitative design can produce stronger evidence around measures that may help healthcare professionals reflect on and learn to cope with adversity.

- qualitative research

- human resource management

- quality in health care

- risk management

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057095

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to focus on methodological issues regarding the definition, development and utilisation of vignette-based methodology to collect qualitative data from healthcare professionals.

Our study provides a broad overview of how vignette-based methodology has been used in qualitative studies involving healthcare professionals over the last two decades.

The review process follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews guideline universally recognised to improve the uptake of research findings.

Although our content analysis considers quality criteria, in line with recommendations for the conduct of scoping reviews, we do not systematically appraise included studies.

Relevant studies may have been excluded in our three-step screening process, as titles and abstracts do not always specify whether the vignette is used when conducting qualitative research.

Introduction

Vignettes are commonly referred to as short hypothetical accounts reflecting real-world situations. Vignettes are presented to knowledgeable individuals who are invited to respond. 1 Generally speaking, vignettes allow participants to clarify and share their perceptions on sensitive topics such as dealing with adversity in challenging environments, discussing team functioning issues or moral dilemmas they face daily, and reflect on potential solutions. Vignette-based methodology in qualitative research appears useful to our research team, which is currently piloting an intervention to co-construct, implement and assess resilience at work among cancer teams, as a means of integrating the knowledge of cancer professionals on how to face adversity. The objective of the scoping review is to learn from prior use of vignette-based methodology in qualitative research in healthcare settings.

Team resilience at work refers to the capacity of team members to face and adapt to adverse situations. 2 Cancer care offers a valuable clinical context to study team resilience at work because professionals face daily adversity with overlapping challenges such as delivering news of a new cancer diagnosis or disease progression, constant changes in therapeutic regimens, frequent staff turn-over and shortages, and increased administrative tasks. 3–7 Cancer team members are exposed to mental health threats such as high stress, anxiety, compassion fatigue and loss of a sense of coherence 8 associated with absenteeism, burnout or depression. 4 5 9–12 While these negative effects of adversity have grown exponentially with each wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, 13 14 solutions to manage and minimise these effects remain understudied. Cancer team members must manage and learn from difficult situations related to their practice context and the pandemic environment. The vignette-based methodology provides an opportunity to reflect and plan supportive interventions and offers an empirically based research approach that is well suited to this complex context.

Vignette-based methodology in qualitative research explores and interprets contextualised phenomena to identify influential factors and understand how participants perceive moral issues or sensitive experiences. 15 It also enables reflexive learning from practice, stimulates exchange on professional responses to difficult situations and supports tailored actions to make sense of adversity. Vignette-based methodology is of interest in disciplines such as psychology, social science, education, medicine and nursing. 16–20 It has been developed and used to collect data on perceptions, beliefs, attitudes and knowledge, 17 19 from individuals or teams, 19 21 through individual or group interviews or questionnaires. 15 18 21 Commonly formatted as written narratives, vignettes can also be presented as audio segments, photographs or videos. 18 21

Empirical studies use different definitions of the vignette and provide little detail about how it is developed and used to collect data. 15 19 21 Such methodological inconsistencies raise questions about the quality criteria of this qualitative approach. 17 Concerns have also been expressed around whether data collection approaches ensure an appropriate distance between the occurrence of sensitive events and the interview 19 and around the need to mitigate the risk that participants provide socially desirable responses. 15 Finally, our preliminary search for studies using vignette-based methodology to collect qualitative data from professionals in cancer care found only one study. 22 These factors emphasise the need to arrive at a working definition of this approach to inform data collection in subsequent qualitative studies and provide the rationale for this scoping review. 23 24

This study aims to clarify the definition of vignette-based methodology in qualitative research and to identify key elements underpinning its development and utilisation in empirical studies involving healthcare professionals.

This scoping review mobilises the Joanna Briggs Institute’s methodological guidelines, 23 which build on the seminal works of Arksey and O’Malley 25 and Levac et al . 26 Scoping reviews examine the number, range and nature of studies relevant to a particular research question and are used to analyse and report available evidence. 27 The present scoping review follows the steps described by Peters et al . 23 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist criteria 24 are followed to report results ( online supplemental appendix 1 ). The protocol was registered prospectively with the Open Science Framework on 1 July 2020 ( https://osf.io/muz4x/?view_only=5943aa0ffb6541d6979ebeedba7464cb ).

Supplemental material

Patient and public involvement.

No patients or public involved in carrying out this scoping review.

Scoping review questions

The questions of the scoping review have a methodological focus: (1) how has vignette-based methodology in qualitative research been defined?; (2) what steps have been involved in developing vignettes to collect qualitative data in studies involving healthcare professionals?; and (3) how is vignette-based methodology used to collect qualitative data from healthcare professionals?

Planned approach

The Population/participants, Concept and Context (PCC) framework, with the addition of the type of evidence source (type of study and type of publication), is used to guide the selection of eligibility criteria and the search strategy. 23 28 PCC generally allows a wide range of articles to be considered for inclusion. The concept of interest is the vignette as used in qualitative research. A preliminary search of qualitative vignette-based methodology development and utilisation with cancer team members found only one study. Therefore, the search was expanded to include qualitative studies as well as systematic and scoping reviews (type of evidence source) in healthcare contexts other than oncology (context), with healthcare professionals in both practice and educational settings (population/participants).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (A) empirical studies with specific focus and/or statements about the development or utilisation of vignettes in qualitative studies involving healthcare professionals in clinical practice, training or continuing education; (B) qualitative study design (action research, intervention research with clinical or educational application and professional practice-based initiatives); (C) written in English or French; and (D) published between January 2000 and December 2020 in journals listed in electronic databases. The search was limited to 2000 due to the very small number of publications prior to that year using vignettes in qualitative research involving healthcare professionals. Exclusion criteria were: (A) absence of the word ‘vignette’ in title, in order to target studies with a clear focus on methodological development or use in qualitative research; (B) background articles or other articles that did not report outcomes from use of vignettes in qualitative data collection; (C) studies using vignette with quantitative or mixed methods design; (D) studies reported in grey literature; and (E) articles without an abstract.

Search strategy

Research team members including researchers and professionals from various disciplines (eg, nursing, psychology, economics, human resources management and medicine) were involved in search strategy preplanning. An academic librarian contributed to determining the databases, search terms, boolean operators and query modifiers ( online supplemental appendix 2 ). A total of five peer-reviewed online databases were searched: Academic Search Complete, CINAHL Plus, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and SocINDEX. The search was supplemented by hand-searching reference lists.

Source of evidence screening and selection

Articles were uploaded to Rayyan, a cloud-based application for systematic reviews. 29 Duplicates were removed before undertaking the three-step screening process 30 : title, abstract and full-text assessment. Two reviewers (DT and AT) independently completed each screening step. 31 Disagreements on article selection and on reasons for exclusion were resolved by consensus through discussion between the two reviewers and two other team members (SL and EG). Reviewers selected and applied the highest reason for exclusion from a screening criteria priority list, which was agreed on ahead of time.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction was performed in two cycles, according to Peters et al ’s recommendations on key information to extract. 23 The first cycle aimed to describe study characteristics (eg, authors, country and year of publication, study phenomenon and setting). The second cycle was based on a thematic analysis for data condensation. 32 The coding grid aligned with our review questions: vignette definition; vignette development (steps described, actors involved/developers, source and format of vignette content); vignette utilisation (study participants, delivery method, introduction items, vignette presentation and handling, interview process, design and strategy for data analysis); and strengths and limitations relating to vignette development or utilisation, advantages or disadvantages of using the vignette and recommendations reported by authors. The coding approach was defined by consensus between research team members (DT, AT, SL and EG). Data extraction was performed using QDA Miner (V.5.0.34). 33

A thematic analysis on the development and utilisation of vignettes, as well as recommendations from authors that emerged from the reviewed articles, were synthesised in charting tables. Several research team meetings were carried out during the iterative data extraction and analysis process. Data matrices were used to display the findings according to the scoping review questions.

Search results

The removal of duplicates and the addition of one record from hand-searching left 157 potentially eligible articles. Screening by title excluded 127 articles, while screening of abstracts excluded 14 more. Full-text assessment excluded an additional six articles. The main reasons for exclusion were wrong concept (not vignette-based methodology in qualitative research) and wrong population (not healthcare professionals). A total of 10 articles were eligible for inclusion in the review. Search results are presented in a flow diagram 34 ( figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

PRISMA flow diagram of article selection process. Adapted from: Page et al . 34 PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Characteristics of included studies

Included studies are published between 2002 and 2020 and involve healthcare professionals from four countries: Australia, 35 Canada, 22 36 Norway 37 and the UK. 38–43 Study settings include oncology, primary care, mental health, public health, hospital care, health and social work, health education and critical care. Various phenomena are investigated, such as quality of care related to professional practices, understanding of policy issues, appreciation of health services, perceptions towards patients and moral or ethical issues. These characteristics are included in tables in the next sections.

Vignette-based methodology in qualitative research

The first question in this review concerns how studies define the vignette-based methodology in qualitative research. While a definition is missing in two articles, 40 41 four articles 22 36 38 39 provide an original definition informed by one or more key references. For example, Morrison (p. 362) 36 defines vignettes as ‘ carefully designed short stories about a specific scenario presented to informants to prompt discussion related to their perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes ’. The other four articles refer to key authors without giving an explicit definition. 35 37 42 43

Vignettes are referred to as short stories about hypothetical characters in specified circumstances that participants are invited to respond to. 35 36 38 42 43 Other elements specified in definitions include the form of the vignette (eg, text), 39 the nature of the stories or scenarios (eg, simulations of real events, fictional or composite) 38 43 or the aim of the vignette (eg, to elicit individuals’ perceptions, attitudes, beliefs and social norms). 36 38

Methodological development of vignettes for qualitative research

The second question of interest pertains to the methodological steps involved in developing a vignette to collect qualitative data from healthcare professionals. Table 1 presents a description of the vignettes in each study, the extent to which development steps are reported, as well as the steps and actors involved in vignette development.

- View inline

Description of vignette development in included studies

Vignettes are designed as stories, 40 scenarios, 35 38 42 43 clinical situations emerging along the cancer trajectory 22 or descriptions of a plausible individual or social situation. 36 37 39 41 Including 1–20 situations, they are presented in written narrative form in all studies but one, which combines narratives and photographs. 36 Three studies use temporally sequenced vignettes. 22 38 40 To emphasise the plausibility of the content, six articles mention the source of inspiration: real-life clinical situations or patient experiences, 22 36 39 41 observational research 43 or situations involving ethical challenges seen in field study. 37

The steps used to develop the vignette are clearly described in four studies. In the other studies, authors are either vague about the steps 36 40 43 or provide minimal to no information. 39 41 42 Although the number of steps ranges from 2 to 8, with various degrees of specification, design and pretesting appear as the most common steps to arrive at the version of the research vignette delivered in interviews. Other steps involve establishing the vignette content and format and choosing a delivery approach (eg, individual or group interview). Drawn either from literature (eg, knowledge from reviews, existing frameworks or guidelines) or from empirical studies, the content is either developed by researchers, sometimes with input from clinical experts 22 or exploratory focus groups of individuals similar to research participants. 38

Strategies are described to improve the internal validity of vignettes (relevance, reliability, effectiveness, completeness, familiarity and intelligibility). Three studies stress the importance of reviewing vignette content, conducting a survey with respondents similar to the targeted audience 37 or obtaining feedback from experts. 35 43 Vignettes are pretested in six studies, through piloting with experts 39 40 or individuals 35 or through group discussion 22 38 ; one study mentions testing the vignettes and interview protocol without providing further detail. 36 Other strategies to improve internal validity include: use of a panel of experts, 38–40 43 use of primary research data 36–39 or framework 22 to develop the content; removal of elements from the vignettes that may bias the interviews 37 ; and selecting a small number of scenarios (up to four) to be included in the vignette. 37

Strategies to increase generalisability include making the vignettes realistic 36 37 43 and comparing pretest responses from experts with responses anticipated by the research team. 22 Researchers 22 35 37 38 40 43 also mention making changes to content, format or delivery method as needed throughout validation and/or pretesting steps to assure internal and external validity.

Utilisation of vignette-based methodology in qualitative research

The third question we explore in the review is how vignette-based methodology is used to collect qualitative data from healthcare professionals ( table 2 ).

Description of vignette-based methodology utilisation in included studies

Studies employ convenience 37 or purposive 35 36 38 39 41 sampling to determine inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants. Sociodemographics (age, gender or sex and years of experience) are reported in three studies, 37 39 41 while participants’ profession is reported in all studies.

Vignettes are delivered through individual interviews in seven studies. 35–38 40–42 The number of individuals varies from 8 to 30. Four studies present the vignettes in group interviews 22 39 41 or team meetings 43 of 2–14 participants. Johnson et al 40 consider that individual interviews are best suited to explore professionals’ personal views, for logistical reasons and to reduce the risk of inhibiting expression due to power differentials between participants. In contrast, Cazale et al 22 use focus groups to observe the interaction between participants, which seems promising to generate data in their study aimed at assessing the quality of care provided by interdisciplinary teams. One study 41 uses both individual and group interviews, without explicit justification.

Six studies report that researchers introduced study objectives to participants, explained ground rules such as confidentiality, the interview procedure and assured them there were no right or wrong answers. This is similar to other qualitative methods.

Various interviewing approaches are adopted in the studies: open discussion, semistructured or structured. Interview guides are used in five studies. 36–40 All studies include questions about the participants’ perceptions, views or beliefs regarding their own experiences or practices. One study includes questions to elicit participants’ thoughts on whether the vignette content reflects their personal experience (plausibility). 38 Another adds questions on how others may have interpreted or behaved in a similar situation, which helps verify that the vignettes describe real-life practice situations and thus contributes to establishing their validity. 37

Some note that the method is generally well received by participants, 35 36 despite two health professionals who ‘ opined that the vignettes were unnecessary to facilitate the dialogue that could have been accomplished by direct questioning ’ (p. 369). 36 Certain issues are also reported regarding the quality of the answers elicited (eg, answers from own perspective instead of others’; answers to avoid disclosing confidential or problematic information; answers tailored to social desirability). 35 37 38

Various qualitative design and data analysis approaches are employed, including thematic analysis of interview responses, hermeneutic analysis, framework analysis, interpretive description or modified grounded theory. Only three studies include information on reliability assessment using content validation by experts, pretest or interview modalities. 22 39 41

Synthesis of recommendations from included studies

A synthesis of the recommendations on vignette development and utilisation is presented in table 3 . These are based on analysis of the strengths and limitations reported in the 10 studies included in this scoping review.

Synthesis of strengths (S), limitations (L) and authors’ recommendations in included studies

Researchers in all the studies report that vignette-based methodology in qualitative research is an effective means of exploring sensitive or difficult topics and eliciting in-depth responses and reflexivity.

Eight authors’ recommendations emerge from our scoping review around the methodology for development of vignettes in qualitative research: (1) follow a rigorous stepwise development process 22 42 ; (2) involve experts who are knowledgeable informants or a multidisciplinary team in refining content 22 38 ; (3) use credible sources such as primary research data, frameworks or literature reviews to develop content 22 38 39 43 ; (4) be mindful of participants’ availability when determining the number of sections or vignettes 35 36 ; (5) avoid content that uses unclear terminology, 38 lacks information (eg, not the full clinical picture), 38 includes too many variables 22 35 or leads to particular interpretations or choices 22 37 ; (6) provide vignettes that are meaningful and allow participants to identify with and reflect on the story 36 38 43 ; (7) use validation strategies and test the quality of the vignette 37 40 ; and (8) pay attention to the delivery, including semistructured interview questions and form of probing 36–38 (eg, a third person format can help create safe distance to explore difficult topics 36 ; consistency in the format: mixing second and third person questions can lead participants to answer most questions based on their personal experience). 36

Our scoping review further suggests a number of recommendations regarding the utilisation of vignette-based methodology: (1) use the vignette consistently with each participant or group of participants to allow systematic data collection 22 35 40 ; (2) make sure the interviewer has the skills to conduct individual or group interviews 22 35 36 ; (3) recognise and try to discourage socially desirable responses 35 ; (4) be cautious about the extent to which it reflects real-world situations for the participants 35 40 41 ; (5) add one facilitator and one observer during focus groups 22 ; (6) reach saturation in data collection 36 37 ; and (7) use validation strategies in data analysis (eg, intercoder reliability assessment; theme validation) 39 and triangulation to reinforce the quality of results. 22 35

This scoping review contributes to clarify the definition of vignette-based methodology in qualitative research, details its development steps, describes its utilisation and assesses its strengths and limitations based on quality criteria for qualitative studies. It can inform planning of future research employing this qualitative approach. Ten studies are included that involve healthcare professionals in various settings.

Main findings

Our results suggest an expanded use of the vignette as a qualitative methodology. Vignette-based methodology is not commonly used in qualitative studies involving healthcare professionals, despite being recognised as a suitable approach for ‘reflecting-on’ and ‘reflecting-in’ practice. 44 The methodology is well suited to intervention research, establishing partnership between knowledgeable actors from the field and researchers to define a problem and potential solutions. 45

During the article-screening process, 112 out of 156 articles were excluded due to ‘wrong concept’ (71,7%); that is, they did not address or use vignette-based methodology in qualitative research (see figure 1 ). One contributing factor to the high exclusion rate is that many articles used the term ‘vignette’ without defining the term. Vignettes are used in the scientific literature in various ways (clinical case reports, training materials, evaluations of clinician knowledge, etc). Our review findings reveal the need to clearly state ‘what’ is vignette-based methodology in qualitative research and describe the logic of its use by researchers.

Vignettes can be used to describe a phenomenon in multiple contexts that are different from qualitative research. We acknowledge that variation may be appropriate across vignette utilisation. However, in qualitative studies, a number of basic principles are considered necessary to assure reliability of analysis: explicit description of the study context and procedures used in data collection and analysis to produce knowledge. 32 Our scoping review shows that vignette-based qualitative research studies often fail to fully describe how these three principles are met. This points to a lack of engagement with standards for reporting qualitative research 46 and compromises replicability and the utilisation of knowledge arising from vignette-based studies. Finally, standards for reporting qualitative research suggest that the title indicates that the study is qualitative or include a commonly used term that identifies the approach. 47

In sum, an article title that states the research method and a clear definition of ‘vignette’ in the report contribute to aligning the research objectives, study design and methods. They allow readers and reviewers to understand the type of vignette study at hand and support the reliability, transferability and usefulness of results. 48

Despite the efforts of authors to clarify the concept, less than half the studies included in our review provide an explicit definition. Based on our scoping review, the vignette-based methodology in qualitative research can be defined as evidence- and practice-informed short stories, scenarios, events or situations in specified circumstances, to which individuals or groups are invited to respond. 1 22 36 39

Details of vignette development are only scarcely reported. Less than half of the studies explicitly report all steps in development. The range of development steps reflects the lack of standardised quality criteria for reporting vignette-based methodology in qualitative research. Greater transparency is needed to establish internal validity and enable study replication, notably around knowledgeable informant involvement in establishing vignette content and/or participating in validation steps.

Our results highlight that vignettes are delivered through individual interviews in most studies, but that some researchers opt for or add group interviews to meet their study objectives. The choice may depend on whether the study seeks to elicit personal views or interaction between participants. However, the choice of interview approach is not always explained.

Our synthesis of strengths, limitations and authors’ recommendations in included articles (see table 3 ) provides an overview of what vignette-based methodology adds to the studies. Some advantages highlighted in included articles are not specific to the vignette development and use. For example, it has been mentioned that it allows the interview to be structured, provides a systematic way of collecting data and facilitates saturation. Other contributions appear to be more specific, notably increasing acceptability to participants when the study phenomenon is sensitive, such as with ethical issues, practice gaps or recovery from challenging clinical situations. By creating a safe distance through use of a fictitious scenario, the method encourages respondents to engage in deeper reflection on sensitive topics that they may otherwise prefer to avoid. More marginally, some authors appreciate the potential flexibility of the vignette (eg, manipulation of certain characteristics). 42 Some authors 22 37 recommend using the vignette in combination with other methods to compensate for limitations. Additionally, Morrison considers that the vignette is a static approach that does not leave enough room for interactions. 36 This point of view suggests that the vignette may not elicit authentic discussion among participants unless the interviewer has the skills to facilitate exchanges.

Our results raise the need to explicitly consider and report strategies to ensure rigour and transparency in both the development of the vignette and the quality criteria of the wider qualitative study design (credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability). 49 Even with well-designed vignette-based studies, limitations in external validity must be documented.

The vignette-based methodology in qualitative research has an added value in intervention research in which the definition of problems and solutions is carried out in partnership between healthcare professionals and researchers. 50 After expert consultation and pretesting, a vignette content that allows an in-depth understanding of a complex and highly contextualised phenomenon where a multitude of factors can, alone or in combination, influence the practice in clinical settings. Vignette-based qualitative studies offer the possibility of reflecting on challenging topics and supporting evidence-based decision making and action in practice and in future research.

Strengths and limitations

Although strategies are employed to ensure the rigour of the review process, we recognise several limitations. This scoping review was conducted to inform qualitative data collection from healthcare professionals using a reflexive approach, which explains why quantitative studies were excluded. We recognise that there is considerable use of vignettes in quantitative research. Their purpose and therefore the quality criteria for their use are categorically different than for qualitative studies, in terms of both vignette development and utilisation. Stakeholders can better understand the complex world of health professionals if researchers move throughout complementary approach to better understand complex issues. 51

The search strategy is limited to empirical studies retrieved from electronic databases after 2000 and excludes grey literature. It covers only a proportion of published literature using vignettes as a qualitative research approach. We are aware that various search terms (eg, vignette, scenario, case report and snapshot) carry meanings that may be used interchangeably. What we attempt is not a meta-level synthesis of vignette-based qualitative research, but the pooling of content from included studies in our scoping review. 52 Because our initial interest is to learn from prior use of vignettes in research in healthcare settings, it is possible that included articles reflect a selection bias related to our methodological focus. The small number of eligible studies reduces the robustness of recommendations for the development and utilisation of vignette-based methodology in qualitative research. The number may reflect our decision to include only articles that feature ‘vignette’ in their title. Moreover, screening was challenging because studies provided little detail about how the eligibility of professional participants was determined or what qualitative approach was used, and mixed-methods was an exclusion criteria in our search strategy.

Despite these limitations, we consider that the evidence around the development steps and utilisation of vignettes that emerges from our scoping review helps deepen our understanding of the method and provides valuable recommendations for future research. While Peters et al 23 suggest that information scientists, stakeholders and/or experts may be consulted to validate the interpretations of scoping reviews, this step appears unnecessary given the diversity of our research team and the small number of included articles.

This scoping review generates a summary of vignette-based methodology and offers guidance regarding the development and use of vignettes in qualitative research involving healthcare professionals, which can be applied in various settings including oncology. Future research may contribute to overcoming identified risks to quality by reporting: (1) an explicit definition of vignette-based methodology as for all qualitative study design; (2) details about vignette development steps (internal validity); (3) rich description of vignette utilisation (external validity); and (4) strengths and limitations based on quality criteria for qualitative studies.

It is expected that future research will more systematically plan and document the development and utilisation of vignette-based methodology and report the research process with sufficient detail to establish how the plausible content of the vignette is associated with study results. Future publications should take into account recommendations from the studies reported in this scoping review and integrate reporting on quality criteria.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants. No research ethics board approval was required since the data were publicly accessible.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Marie-France Vachon for her expertise regarding vignettes for healthcare professionals in oncology, as well as Nathalie St-Jacques, academic librarian at the Université de Sherbrooke, for her support with the search strategy.

- Hartwig A ,

- Johnson S , et al

- Williams JH ,

- Hogan PF , et al

- Lynch J , et al

- Hlubocky FJ ,

- Lavoie‐Tremblay M ,

- Gélinas C ,

- Aubé T , et al

- DesCamp R ,

- O'Rourke KM

- Dyrbye LN ,

- Erwin PJ , et al

- Banerjee S ,

- Murali K , et al

- Shanafelt TD , et al

- Flaskerud JH

- Peabody JW ,

- Glassman P , et al

- Jenkins N ,

- Fischer J , et al

- Tremblay D ,

- Peters MDJ ,

- Godfrey CM ,

- McInerney P , et al

- Tricco AC ,

- Zarin W , et al

- Colquhoun H ,

- Lockwood C ,

- McInerney P

- Ouzzani M ,

- Hammady H ,

- Fedorowicz Z , et al

- Papaioannou D ,

- Stoll CRT ,

- Fowler S , et al

- Huberman AM ,

- Provalis Research

- McKenzie JE ,

- Bossuyt PM , et al

- Jackson M ,

- Harrison P ,

- Swinburn B , et al

- Andrews JA ,

- Will CM , et al

- Johnson M ,

- Jiwa M , et al

- Thompson T ,

- Barbour R ,

- Richman J ,

- Spalding NJ ,

- Sainsbury P ,

- O'Brien BC ,

- Harris IB ,

- Beckman TJ , et al

- Carter SM ,

- Thompson D ,

- Aroian KJ , et al

- Terral P , et al

- Griffiths P ,

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

Supplementary materials

- Atsushi Minami 1 , † ,

- Takehito Tanzawa 2 , * , † ,

- Zhuohao Yang 3 ,

- Takashi Funatsu 3 ,

- Tomohisa Kuzuyama 1 , 5 ,

- Hideji Yoshida 4 ,

- Takayuki Kato 2 and

- Tetsuhiro Ogawa 1 , 5 , *

- 1 Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo , Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan

- 2 Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University , Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan

- 3 Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, The University of Tokyo , Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan

- 4 Faculty of Medicine, Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University , Takatsuki, Osaka 569-0801, Japan

- 5 Collaborative Research Institute for Innovative Microbiology, The University of Tokyo , Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan

- ↵ * Corresponding authors Correspondence to Tetsuhiro Ogawa ( atetsu{at}g.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp ) or Takehito Tanzawa ( takehito.tanzawa{at}protein.osaka-u.ac.jp ).

↵ † These authors contributed equally: Atsushi Minami, Takehito Tanzawa

Ribosomes consume vast energy to synthesize proteins, so controlling the ribosome abundance is a significant concern for cells. Ribonucleases mediate ribosome degradation in response to stresses, while some ribosomes deactivate translational activity and protect themselves from degradation, called ribosome hibernation. RNase T2 is an endoribonuclease found in almost all organisms, and they are thought to be involved in the degradation of ribosomal RNA. Although it was recently reported that the activity of Escherichia coli RNase T2, called RNase I, depends on the environmental conditions, the regulation mechanism remains elusive. Here, we report how rRNA degradation by RNase I is regulated by hibernating ribosomes. Combining the biochemical, cryo-electron microscopy, and single-molecule analyses, we found that hibernating ribosome is an inhibitor by forming a complex with RNase I. Moreover, RNase I does not bind to the translating ribosome, so rRNA is protected. On the other hand, RNase I degrades the rRNA of each subunit dissociated from stalled ribosomes on aberrant mRNA by trans -translation. Under stress conditions, and even in the actively growing phase, some ribosomes are stalling or pausing. Although such ribosomes were thought to be recycled after being rescued, our results add a new insight that they are not recycled but degraded. These findings have broad implications for understanding the regulation of ribosome levels, which is critical for cellular homeostasis and response to environmental stresses.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared no competing interest.

- Received July 29, 2024.

- Revision received July 29, 2024.

- Accepted July 29, 2024.

- © 2024, Posted by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

The copyright holder for this pre-print is the author. All rights reserved. The material may not be redistributed, re-used or adapted without the author's permission.

Contributors DT designed and coordinated the study and led the entire scoping review process. DT (guarantor) accepts full responsibility for the finished work and the conduct of the study, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish. She drafted the first version of the manuscript with AT and SL. AT and NT were involved in the data analysis and data charting. NT, TGP, KK, KB, SL and EG assisted with study planning, data collection and final interpretation. All authors critically revised the draft version and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding This study was funded by the Réseau de recherche en interventions en sciences infirmières du Québec – Quebec Network on Nursing Intervention Research (RRISIQ) (Award/Grant number is not applicable; grant awarded under the 'Projets Intégrateurs 2019' Program: https://rrisiq.com/fr/soutien-la-formation-et-la-recherche/liste-octrois/projets-integrateurs ). Complementary support was also provided by the 'Chaire sur l'amélioration de la qualité et la sécurité des soins aux personnes atteintes de cancer' and by the School of Nursing of the Université de Sherbrooke (award/grant number is not applicable).

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Vignettes: an innovative qualitative data collection tool in Medical Education research

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2024

- Volume 34 , pages 975–977, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sylvia Joshua Western ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4397-6746 1 ,

- Brian McEllistrem 1 ,

- Jane Hislop 1 ,

- Alan Jaap 1 &

- David Hope 1

919 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This article describes how to make use of exemplar vignettes in qualitative medial education research. Vignettes are particularly useful in prompting discussion with participants, when using real-life case examples may breach confidentiality. As such, using vignettes allows researchers to gain insight into participants’ thinking in an ethically sensitive way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Ethical dilemmas and reflexivity in qualitative research

An Exploration of Nursing Students’ Experiences Using Case Report Design: A Case Study

Exploring the value of qualitative research films in clinical education.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Vignettes are written, visual, or oral stimuli portraying realistic events in a focussed manner, purposefully aligned with the research objectives and paradigms to elicit responses from research participants [ 1 ]. They have been used in qualitative research to explore physical, social, and mental health–related topics. Although clinical vignettes are widely used in teaching and assessment, vignettes are under-utilised as a research tool in medical education. In this article, we outline the ways in which we found vignettes to be helpful in addressing our research aims prompting a conversation on how they might be used in other medical education research contexts, particularly when working with sensitive issues.

We used vignettes within individual semi-structured interviews, to explore how medical educators interpreted different test-wise behaviours (“ skills and strategies that are not related to the construct being measured on the test but that facilitate an increased test score ”[ 2 ]). We opted to use vignettes for the following reasons:

Akin to clinical vignettes, they enable usage of anonymised and fictionalised version of real-life case studies, protecting the identity and confidentiality of the original individuals [ 3 ]. Vignettes retained the essence of the event but potential identifiers or personal information from the original were redacted or anonymized.

Realistic scenarios support the exploration of sensitive topics which can generate authentic ethical dilemmas. Instead of asking “Have you ever tried to trick your examiner into giving you more marks”? - a question which might cause distress or harm to participants, we could posit a vignette and ask our participants for a third-person perspective. Vignettes therefore promote participants’ psychological safety by providing an alternative non-confronting and safer avenue to discuss value-laden constructs [ 1 ].

When discussing complex ambiguous topics, they provide a focus to help participants orient to the specific matter at hand [ 3 ]. Vignettes help define and communicate the context, setting, character, and situation succinctly.

Using an established framework of Skilling & Stylianides [ 1 ], we constructed five vignettes portraying a spectrum of test-wise behaviours. We drew on informal conversations with stakeholders, online forums, our professional experience, academic literature, and knowledge of the local context to draft the vignettes. Our aim was to understand how people make meaning, what guided their decisions and reactions to test-wise behaviours. Following feedback from experts and several pilot interviews, we revised the vignettes. As such we found that the process of building vignettes was iterative, collaborative, and continuously evolving.

Using previous case studies employing vignettes for data collection, we reflected on the iterative process of constructing, peer and expert reviewing, piloting, and deploying vignettes to eight participants. Participants were staff and students at Edinburgh Medical School. By contemplating the decision-making pathway that aided vignette construction, studying the reflective notes of the interviewer, thematically analysing interview transcripts, and engaging in an ongoing discussion and feedback loops with our expert and supervisory panel, we identified eight factors making vignettes especially useful:

By controlling the age, sex, and ethnicity of subjects, we could explore how participants interpreted and reacted to different test-wise behaviours of different students.

Following discussion, participants commented on the realism of the vignettes, allowing for iteration of the vignettes over time.

Vignettes facilitated subjective interpretation of complex situations and allowed for intentional reflection on thoughts and actions.

Participants had the agency to discuss their own attitudes in relation to the vignettes and used them to explore their real-life experiences.

We tailored the frequency and type of vignette based on the participant’s role, and selected vignettes to explore issues under-discussed in previous interviews.

Criticising real actions and guidelines can be challenging. Discussing hypothetical vignettes allowed for openness, honesty, and pragmatic answers.

Exposing participants to novel vignettes helped the researchers compare their expectations and beliefs to participant views. Participants found the vignettes plausible, which suggested the researchers had a defensible understanding of the topic.

We can compare the interpretation of the same vignette by different individuals in different roles to understand the underlying rationale for their differing perspectives. Follow-up interviews allow for the exploration of changes over time.

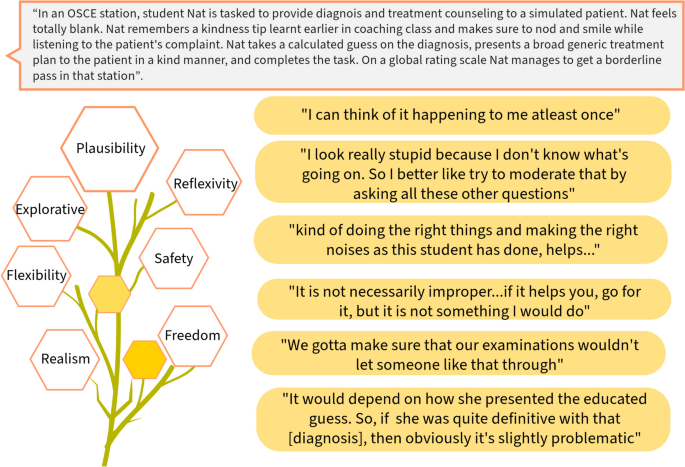

Figure 1 shows an exemplar vignette with excerpts of participant responses. Rather than ask how they would feel if an exam candidate used false empathy to conceal their lack of content knowledge, we used Nat vignette (in Fig. 1 ) as a realistic case study to facilitate discussion. The broader themes in the left side of the infographic (Fig. 1 ) speak to some of the factors identified previously, acting as a teaser facilitating the readers to think through the participant responses. For example, the snippet “I can think of it happening to me at least once” connects to plausibility and realism - the participant thinks that this is a plausible scene in their context, and it seems real to them.

Example vignette with excerpts of participant responses

Firstly, a challenge we faced pertained to participant engagement. While all participants found the example vignette (in Fig. 1 ) both plausible and relatable, the pattern of engagement varied among them. Some used it as a springboard to delve into their own real-life stories, while others found it challenging to reconcile the artificial and hypothetical nature of the vignette. The effectiveness of vignettes hinges on participant engagement. Drawing from our experience and the supporting literature, we found that vignettes must be relatable [ 3 ], plausible [ 3 ], and situated in context [ 1 ]. Participants must be oriented to the vignette method before interview and be given the vignettes at appropriate times during the interview. It is essential when using vignettes to gauge and promote engagement during the interview. Tailored questions and prompts are helpful strategies to promote such engagement. Secondly, we agree that however realistic vignettes are, they are “not real”, therefore participants’ responses to hypothetical vignettes might not perfectly align with their reactions to real-life situations, for instance, considering their underlying motivational relevance to the different contexts - research environment and real-life [ 3 ]. Researchers should remain aware of these challenges and interpret their findings with caution [ 3 ].

In conclusion, our use of vignettes was an innovative alternative to using high-stakes, confidential real-life case examples in qualitative research. Usage of vignette opens new possibilities in medical education research: they can be used within questionnaire surveys, individual and focus group interviews, or as ethnographic field notes. They offer a versatile approach to allow exploration of high-stakes, sensitive, and ethically contentious issues with participants in a safe way. Therefore, researchers can benefit significantly from applying vignettes in their own research.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Skilling K, Stylianides GJ. Using vignettes in educational research: a framework for vignette construction. Int J Res Method Educ. 2020;43(5):541–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2019.1704243 .

Article Google Scholar

American Psychological Association. Testwise. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/testwise . Updated April 19, 2018. Accessed 20 May 2024.

Jenkins N, Bloor MJ, Fischer J, Berney L, Neale J. Putting it in context: the use of vignettes in qualitative interviewing. Qual Res. 2010;10(2):175–98.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Sylvia Joshua Western, Brian McEllistrem, Jane Hislop, Alan Jaap & David Hope

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sylvia Joshua Western .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Western, S.J., McEllistrem, B., Hislop, J. et al. Vignettes: an innovative qualitative data collection tool in Medical Education research. Med.Sci.Educ. 34 , 975–977 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-024-02074-0

Download citation

Accepted : 10 May 2024

Published : 05 June 2024

Issue Date : October 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-024-02074-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Medical education

- Data collection

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 11 February 2014

Using vignettes in qualitative research to explore barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of prevention of mother-to-child transmission services in rural Tanzania: a critical analysis

- Annabelle Gourlay 1 ,

- Gerry Mshana 2 ,

- Isolde Birdthistle 1 ,

- Grace Bulugu 2 ,

- Basia Zaba 1 &

- Mark Urassa 2

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 14 , Article number: 21 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

47k Accesses

98 Citations

Metrics details

Vignettes are short stories about a hypothetical person, traditionally used within research (quantitative or qualitative) on sensitive topics in the developed world. Studies using vignettes in the developing world are emerging, but with no critical examination of their usefulness in such settings. We describe the development and application of vignettes to a qualitative investigation of barriers to uptake of prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) HIV services in rural Tanzania in 2012, and critique the successes and challenges of using the technique in this setting.

Participatory Learning and Action (PLA) group activities (3 male; 3 female groups from Kisesa, north-west Tanzania) were used to develop a vignette representing realistic experiences of an HIV-infected pregnant woman in the community. The vignette was discussed during in-depth interviews with 16 HIV-positive women, 3 partners/relatives, and 5 HIV-negative women who had given birth recently. A critical analysis was applied to assess the development, implementation and usefulness of the vignette.

The majority of in-depth interviewees understood the concept of the vignette and felt the story was realistic, although the story or questions needed repeating in some cases. In-depth interviewers generally applied the vignette as intended, though occasionally were unsure whether to steer the conversation back to the vignette character when participants segued into personal experiences. Interviewees were occasionally confused by questions and responded with what the character should do rather than would do; also confusing fieldworkers and presenting difficulties for researchers in interpretation. Use of the vignette achieved the main objectives, putting most participants at ease and generating data on barriers to PMTCT service uptake. Participants’ responses to the vignette often reflected their own experience (revealed later in the interviews).

Conclusions

Participatory group research is an effective method for developing vignettes. A vignette was incorporated into qualitative interview discussion guides and used successfully in rural Africa to draw out barriers to PMTCT service use; vignettes may also be valuable in HIV, health service use and drug adherence research in this setting. Application of this technique can prove challenging for fieldworkers, so thorough training should be provided prior to its use.

Peer Review reports

Vignettes are short stories about a hypothetical person, presented to participants during qualitative research (e.g. within an interview or group discussion) or quantitative research, to glean information about their own set of beliefs. They are usually developed by drawing from previous research or examples of situations which reflect the local context, creating a story that participants can relate to. Participants are typically asked to comment on how they think the character in the story would feel or act in the given situation, or what they would do themselves. As the focus is on a third person, vignettes can be advantageous in research on sensitive topics where the participant may not feel comfortable discussing their personal situation and may conceal the truth about their own actions or beliefs. They can also, through normalisation of the situation, encourage participants to reveal personal experiences when they feel comfortable to do so [ 1 – 4 ].

Vignettes have traditionally been used in the developed world in (predominantly quantitative) research on psychology and potentially sensitive social and health issues such as sexual health, HIV, mental health, stigmatisation, violence, and in specific vulnerable populations such as children and drug users [ 1 , 2 , 4 – 13 ]. Hughes, and Barter and Renolds reflected critically on the methodology of vignettes with reference to their own research and other studies conducted in the developed world, concluding that the technique can be a valuable research tool despite debates surrounding their use: primarily the extent to which vignette responses mirror social reality [ 1 , 4 ]. Studies from the developing world (including Africa) using vignettes have emerged more recently [ 14 – 24 ], but none have critically examined the use of vignettes in such settings. These studies have mainly focussed on similar topics to those investigated traditionally in North America and Europe, such as sexual health, mental health and stigma, but also include areas such as malaria and public health campaigns.

Very little qualitative research about HIV services in this setting, particularly prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV or drug adherence (in the push for universal testing and treatment), has used vignettes to elicit perspectives of patients (or providers) regarding service or drug use. The few examples include Varga and Brookes’ study in South Africa, based on the narrative research method of the World Health Organisation [ 25 ]: vignettes were developed during workshops with ‘key informants’ and presented during focus groups and surveys with pregnant HIV-positive adolescents to investigate barriers to participation in PMTCT services [ 24 ]. Bentley et al. also used vignettes to investigate perceptions of HIV-positive mothers regarding breastfeeding practices and nutrition in Malawi [ 26 ]. Varga and Brookes discussed methodological implications of their approach, reflecting that adolescent mothers spoke more easily about their own experiences after discussing the story of another teenager, and suggesting that in-depth interviews (IDI) exploring personal experiences can be useful in verifying and understanding responses towards the vignette. However, neither paper evaluated the specific challenges nor advantages of applying vignettes in their setting, for example the extent to which respondents understood the directions they were given, or how well fieldworkers facilitated discussions or interviews containing vignettes.

Global commitments have been made to improve uptake of PMTCT services [ 27 ] in view of the low coverage noted in many African countries [ 28 ]. An emerging body of research is exploring reasons for low access and usage of PMTCT services: barriers include sensitive issues such as stigmatisation regarding HIV status, fear of disclosure to partners or other relatives, and psychological barriers including denial [ 29 ].

The potential for reporting bias in studies on barriers to PMTCT service use in sub-Saharan Africa has been noted [ 29 ], and in our study setting, under-reporting by women of other socially sensitive outcomes (e.g. number of sexual partners) was reported [ 30 ]. We therefore expected that a number of HIV-positive women would not admit to difficulties they faced when accessing PMTCT services, or would feel uncomfortable discussing such issues during interviews. Vignettes could consequently be a valuable and under-used tool in PMTCT/HIV research and drug adherence more widely. They may also offer a contribution to the range of methods available to reduce the social desirability biases encountered with self-reporting of outcomes in HIV, sexual and reproductive health research [ 31 – 33 ]. There is some discussion over whether responses to vignettes may also be socially desirable, particularly when respondents are asked how they themselves would act in the scenario presented. However, asking first how the fictional character would behave and why is thought to reduce the pressure to answer with socially desirable outcomes [ 4 ]. In this paper we describe the development and application of a vignette to an investigation of barriers and facilitating factors to uptake of PMTCT services in rural Tanzania. Our objectives for using the method were 1) to create a comfortable environment for IDIs and encourage women to openly discuss difficulties they or acquaintances faced in using PMTCT or maternal and child health services, and 2) to generate data on barriers and facilitating factors to uptake of PMTCT services from the perspective of HIV-positive and HIV-negative mothers, fathers and relatives. We critique the successes and challenges associated with employing vignettes in this setting, in order to determine the feasibility and utility of using this technique in qualitative investigations more widely in sub-Saharan Africa.

Study purpose and context

The study fieldwork was conducted between May and June 2012 in Kisesa, a rural area in north-west Tanzania, to identify barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of PMTCT services, and ways of overcoming the issues identified. Demographic surveillance and HIV sero-surveillance has been conducted in this community since 1994 [ 34 ]. Four health facilities offer antenatal clinic (ANC) and PMTCT services in the community: a health centre in the trading centre (also including an HIV care and treatment centre), and 3 dispensaries in rural villages (providing an intermittent PMTCT service depending on availability of HIV test kits and prophylactic drugs).

Study procedures

A variety of qualitative methods were used, including participatory learning and action (PLA) group activities, and IDIs incorporating a vignette. Before commencement of the study, fieldworkers received one week of training on relevant research methods and the topic (PMTCT). Training emphasised the participatory element of the PLA activities, as fieldworkers had prior experience of and training in conducting interviews and facilitating focus group discussions, but less experience of leading participatory fieldwork. After familiarisation with the PLA protocol, fieldworkers practised the activities with volunteer participants. The protocol was revised after observing practice sessions and listening to feedback from fieldworkers, (to shorten or simplify some activities), and after conducting the first PLA activity.

Development of the vignette

The vignette was developed through PLA activities conducted with 3 groups of men and 3 groups of women from different residence areas, each group comprising 8–12 participants. Participants were selected from a sampling frame of men and women aged 15–60 who had at least 1 child. This selection was random, with the exception of a few female HIV-positive individuals (‘seeds’) who were purposively selected from the sampling frame by the principal investigator using the community HIV sero-surveillance data. Female groups included 1–5 HIV-positive ‘seeds’ (see Buzsa et al. for details of the seeded focus group method [ 35 ]). Fieldworkers were unaware of the HIV status of all individuals on the recruitment lists and those participating in the activities. Each PLA was facilitated in Kiswahili (commonly spoken national language) by an experienced fieldworker of the same sex as participants. A second fieldworker took notes on the content of discussions, details of the role-play storyline and behaviours of characters, as well as general observations of the group dynamic. The majority of sessions were attended by the principal investigator. Activities were audio-recorded following informed consent from participants.

PLA activities included brainstorming and ranking of barriers, role-playing and group discussion (Table 1 ). Before the role-plays, fieldworkers facilitated a discussion to identify the central characters that would be involved in a woman’s pregnancy and delivery. Thereafter, the participants were instructed to invent a storyline of a (fictitious) woman who discovers she is HIV-positive at ANC, thinking of the issues that a real woman in their village would face and the decisions she would make when trying to use PMTCT services. Participants then acted the play to the facilitator and observers. De-briefing sessions with fieldworkers were conducted following each PLA activity, informing an initial analysis of emerging themes which was used together with PLA notes by the project investigator to draft the vignette.

To compose the vignette storyline, unifying and contrasting elements of the role-plays were identified. Discussions following the role-plays, during which facilitators discussed how realistic the storylines were, were then analysed to confirm unifying elements, or resolve differences between the stories. Themes emerging from other activities, particularly barriers deemed most important in the ranking exercise, were also considered. The final vignette also needed to be viable given the character’s profile, for example, to represent the issues that the character would face considering their residence, marital status or family circumstances. The aim was to present a story that was familiar to most participants (touching on personal experiences, or experiences of acquaintances in their community), but that also achieved the objective of making women feel comfortable to admit to any difficulties they faced (so, for example, a more extreme case of a woman failing to access several of the services was chosen). Overly emotional circumstances or events (e.g. teenage pregnancy or death of a baby) which might derail the interview were avoided.

Once developed, the vignette and associated questions were incorporated into an interview discussion guide, along with open-ended questions about the personal experiences of the respondent during pregnancy, delivery and infant feeding. As conceived in the original study design, fieldworkers then received an additional day of training on the concept and use of the vignette, including examples of other studies employing this technique [ 24 ], and on confidentiality (particularly if participants disclosed their HIV status during the interviews). This additional training session was intended to give fieldworkers the chance to familiarise themselves with and discuss the vignette developed from the PLAs, and to ensure the associated methods were fresh in fieldworkers’ minds prior to commencing the interviews. Fieldworkers were asked to review the vignette, and comment on how well it reflected the role-plays and major themes identified from the PLAs (no amendments were suggested). They were instructed to probe for whether responses to the vignette (what participants thought the character in the story would do) reflected real life in their community. After training, fieldworkers practised the questionnaire among themselves and with volunteer participants.

Use of the vignette

Twenty-one IDIs with HIV-positive (n = 16) and HIV-negative mothers (n = 5) who had recently delivered a child (since 2009) were conducted in Kiswahili by the same fieldworkers that facilitated the PLAs. Mothers were recruited purposively for interview from the PLA activities (and had therefore not necessarily attended clinic-based services, n = 11), and from each of the 4 health facilities in Kisesa by clinic nurses (n = 10). On completion of the PLA activities, each participant was asked to come forward, separately, to receive their travel compensation (5000 Tanzanian shillings, or approximately 3 USD), and asked if they were interested in being contacted for personal interviews in the future. Facilitators only scheduled specific appointments for interview with selected HIV-positive and negative participants, based on coded lists prepared by the principal investigator using community surveillance data. Facilitators were unaware of the HIV status of participants at the time of recruitment. For the clinic-based recruitment, each nurse was asked to invite and schedule interview appointments for at least two HIV-positive women who were pregnant or had recently given birth, during private consultations with their clients at antenatal or child follow-up clinics. Researchers did not have access to any clinic data for the recruitment.

Three interviews with partners/relatives of HIV-infected mothers were also conducted: women who had disclosed their HIV status during the IDIs were asked if their male partner, or otherwise a female relative, could be contacted for interview.

The same vignette was used in all interviews, and was read out to participants. Interviews lasted between one and three hours, and were audio-recorded after obtaining consent from the participant.

Critical analysis

Critical analysis of the vignette methodology was guided by the following key questions:

Was the vignette method developed and implemented as intended? This includes how well the vignette was developed for the study context, delivered by interviewers and received by participants, in order to assess the feasibility of the approach. To answer this evaluation question, we: (a) reflected on the successes and challenges in developing the vignette; and (b) assessed IDI transcripts for any difficulties in interpretation of the vignette by the participants or fieldworkers, including confusion, misunderstandings or delays during the vignette section of the interviews, and whether participants considered the final vignette to be realistic. In analysis of the transcripts (audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim, translated into English, and the resulting data managed using NVIVO 9), codes were created to capture the way participants responded to the vignettes, and how fieldworkers dealt with their answers.

Did the vignette method achieve its intended objectives? To this end, we gauged from transcripts whether the vignette helped to: (a) make participants comfortable during the interview, e.g. to discuss their personal experiences with ANC/ PMTCT services and HIV status; and (b) generate useful findings (data) about barriers and facilitating factors to PMTCT uptake, analysed through a framework approach which included thematic analysis to develop the coding scheme for barriers to PMTCT service uptake. We considered data quantity and quality, including any difficulties in interpretation of the data during analysis.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Lake Zone ethical review board of Tanzania, the Tanzanian Medical Research Coordinating Committee, and by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine ethics committee.

Summary of the vignette developed

The final vignette described the story of a pregnant woman living in a remote rural village who discovers her HIV-positive status at ANC, faces negative reactions from her partner upon disclosure of her HIV status, is unable to return to the clinic for further PMTCT services (including anti-retroviral drugs) and gives birth at home fearing involuntary disclosure to other relatives. The story was split into 3 sections, with questions after each section about what the woman would most likely do in her situation. Details of the vignette and questions used in the in-depth interviews, excluding probes, are presented in the following section.

Details of the vignette