Go to contents

- Publications

- Economic analysis and research

Working Papers

The aim of the Working Papers series is to disseminate research papers on economics and finances by Banco de España researchers. The Working Papers are published once they have successfully come through an anonymous evaluation process. Through their publication, the Banco de España seeks to contribute to the economic analysis and knowledge of the Spanish economy and its international context.

The opinions and analyses published in the Working Papers series are the responsibility of the authors and are not necessarily shared by the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.

How to use the calendar: use the arrow keys to navigate the calendar. Press the arrows to navigate by days of the month. Press shift and the arrows to navigate by month. Press control and the arrows to navigate by year.

The start date cannot be after the end date

1180 results found with the selected filters

- Última Página

Shortcuts to...

Economic Research Portal

Contact Publications Unit

- Telephone: (34) 91 338 5043

- Contact form

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Spanish Economic-Financial Crisis: Social and Academic Interest

Noelia araújo-vila, jose antonio fraiz-brea, arthur filipe de araújo.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2019 Aug 12; Accepted 2020 Apr 10; Issue date 2020.

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted research re-use and secondary analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the World Health Organization (WHO) declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic.

The present study analyses the interest of both experts and the general population in the economic-financial crisis that has affected Spain up until 2019. To examine the interest of the general users, Google searches were analysed through the Google Trends tool. Meanwhile, the interest of scholars was assessed through the analysis of academic papers published on Scopus, one of the most relevant peer reviewed literature database. To this end, a Scopus search was made for papers containing the fragment “Spanish financial crisis” on their tittles, abstracts, or keywords, which ensued a sample of 632 studies. Findings show that the Spanish financial crisis worries the general population as well as scholars. Peaks in searches by general internet users take place in the years preceding the crisis (2004 and 2005) as well as throughout its duration (2008, 2010, and 2012). Accordingly, the academic interest has also grown substantially up from 2008.

Keywords: Crisis, Spain, Economy, Finance, Social interest, Google Trends tool, Scopus

Introduction

The years preceding the beginning of the Spanish financial crisis—2002–2007—are characterised by a cumulative economic imbalance. Many countries had extremely negative checking account balances, while others achieved atypical surplus values, which led to a global financial crisis. Some countries had loose monetary policies, and at the same time, a great amount of savings. This led to the inflation of assets’ prices, especially real state, which came to be known as the real estate bubble (García 2005 ).

In Spain, construction was financed by international loans. The instability in the construction industry led to high rates of indebtedness, which soon affected the country’s whole economy. An excessive amount of money was being loaned to an industry that was no longer profitable. In this context, banks were increasingly uncertain about whether the debts would be liquidated. Moreover, productivity problems tend to lead to future economic issues. In the years preceding the crisis, Spain’s GDP grew more than that of the United Kingdom and the United States (EU-KLEM 2013 ). This was already a sign that something was not right, or that, at the very least, the situation was temporary and unrealistic. A significant part of this growth was caused by the construction industry, which was responsible for 25% of the country’s economic growth between 2000 and 2007. As García ( 2005 ) points out, this was caused by the increase in working hours and the intensive use of technological capital.

The so-called real estate bubble led to the beginning of a global liquidity crisis in the banking system, which was intensified by the frequent trade of complex and structured financial products. Initially, this crisis did not affect Spain, as the national banks had focused on retail banking and refrained from selling structured mortgage products (Alonso-Almeida and Bremser 2013 ). However, economic-financial problems brought about by the global recession increased the perceived risk and the real estate market’s adjustment, which eventually reached Spain as well (Álvarez 2008 ).

The present work analyses the interest demonstrated by both the general population and economic scholars (and those from related areas) in the economic-financial crisis that affected Spain up until the observed period (2019). Naturally, the health crisis currently being faced by the whole world due to the outbreak of COVID-19 is an even bigger problem, which is expected to have catastrophic consequences for many countries’ economies, including Spain. In this context, it is important to observe that the present research does not consider such phenomenon, which started after the data collection and analysis period. Regarding the methodological steps carried out as part of this investigation, first the extant literature on the Spanish financial crisis was systematically reviewed, which allowed the authors to understand the factors that led to this situation. Then, to achieve this paper’s objective, the interest of the general population was assessed through the analysis of Google searches on the subject throughout the selected timeframe (2007–2019). Meanwhile, the interest of academics was examined through the analysis of scientific papers published on the Scopus database during the same period.

Theoretical Overview: The Origins of the Spanish Crisis

Since the end of the twentieth century, Spain had been one of the fastest growing and most successful economies in Europe. Immigration, low interest rates, and a recently liberalised and modernised economy had contributed to this great economic status (Royo 2009 ). This condition, however, was interrupted in 2007, when the country started facing a severe economic recession. Although the global economic crisis significantly contributed to this deceleration, domestic imbalances have also played an important role. In this context, 2007 is arguably the year when the financial crisis reached Spain, along with many other European countries.

In the Spanish instance, the crisis was the result of a 5-year period of high liquidity in the financial market (Álvarez 2008 ). In other words, during this time, it was particularly easy to convert any financial asset into money with minimal loss. This is shown by the increase in monetary aggregates (Adrian and Shin 2008 ) noticed in this period, which led to an overcapacity of the financial system. This, in turn, led to a general state of distrust, in which neither employers nor families were willing to not take credit. The only cases in which credit was taken were those when people needed to renew their debts or cover their losses. Naturally, as capitalist economies are based on credit, such situation would necessarily have a negative impact on the country’s economy.

Along with this deterioration of economic conditions, a poor management of the situation by the Bank of Spain, the dependence on wholesale financing, and weaknesses in the regulatory framework, all contributed to this recession (Royo 2013 ). However, the key factor that led Spain to the current crisis was the channelling of the financial sector into the real estate market (Alvarez 2008; Montalvo 2014 ; Taylor 2009 ). The so-called system of perverse incentives, adopted as a temporary solution to fund construction activities, made the real estate market very attractive (Montalvo 2014 ). For the families, buying a house started to look like a very attractive proposal.

For the sake of comparison, in the United States, there is the “lease with the option of purchase” model, which became a very favourable option, even for those who could not afford the mortgage payments. Moreover, if the prices happened to increase, which was expected, all parts would benefit from capital gains (Case et al. 2012 ). On the other hand, if prices remained stable, one could simply stop paying the mortgage and lose the purchase option. In this case, the deal would effectively become a regular rent. Another incentive was the barriers of entries, through which people could also request a loan (Mayer et al. 2009 ).

In Spain, however, the scenario was quite different, as the financial product normally employed for the purpose of buying a house is the personal loan with mortgage. In such a deal, if one does not liquidate the debt, they must give back the house. Nevertheless, the general belief was that there was an incredibly low chance of decrease in prices, which encouraged many families to buy houses anyway (García-Montalvo 2006 ). There was a whole chain of factors that encouraged this model of purchase. For example, bank workers needed to sell mortgages in order to hit sales targets and gain bonuses. Therefore, they lowered the criteria for granting this type of loan (Montalvo 2014 ). Moreover, all this housing construction and urbanisation methods did not take place in an institutional void (García 2010 ). Part of the problem was exactly the lack of spatial planning. More precisely, as observed by Maldonado and Pérez ( 2008 ), specific plans for urban development either did not exist or were totally disregarded.

The described scenario led the Spanish construction industry to a great recession, which significantly affected the country’s economy (Kapelko et al. 2014 ). The difficulty in liquidating loan payments was also linked to a decrease in the demand for finished buildings (both residential and non-residential), which resulted in a large amount of unsold real state (Vergés 2011 ). In sum, as concluded by Stiglitz ( 2010 : 21) Spain allowed a massive real estate bubble to arise, and now faces an almost total collapse of this market.

As opposed to the United States, however, Spanish banks were more prepared to endure this trauma, due to the country’s banking regulations. Nevertheless, they country’s economy had much greater losses. This led to a general distrust by bank clients, which, as concluded by Carbó-Valverde et al. ( 2013 ), is an indicator of a significant negative impact of banks’ activities in the economy. Moreover, the bursting of the real estate bubble contributed directly and indirectly to almost 2.3 million job losses and a large private debt (García 2010 ), which further aggravated the situation and forced the government to save banks by financing them with foreign savings.

Therefore, Spain was one of the European countries where the late 2000′s global economic crisis had the most devastating outcomes. This happened due to internal factors that amplified the crisis’ effects, especially the country’s massive real estate bubble.

Methodology

The present study examined the interest of two distinct groups in the Spanish financial crisis: 1. the general internet user; and 2. scholars and specialists in economy and related areas. The interest of the first group was assessed with the help of Google Trends, a tool that allows researchers to examine general trends in Google searches. Google searches were selected as an indicator of the general internet users’ interest because Google is the most popular web searcher in the world (eBizMBA 2018 ). The interest of the second group was assessed through the examination of scientific papers published on Scopus’s database, which is one of the peer-reviewed literature databases with the highest number of citations and abstracts (Andalial et al. 2010 ; Bosman et al. 2006 ).

The analysis carried out through Google trends encompassed searches made with the keywords “crisis Española”, “crisis financiera española”, and “Spanish financial crisis”, made worldwide up from 2004 (year in which the tool started registering searches). This allowed the authors to verify whether the general internet user’s interest in the topic increased up from 2008, the year after the beginning of the crisis.

The analysis of articles published on Scopus was a slightly more complex, due to the nature of the database. First, a search for papers containing the fragment “Spanish Financial crisis” in their tittles, abstracts, and keywords was made. The phrase in English was adopted for the search because most studies in the database are in in this language. A total of 632 works was found, from which 49% had been published between 2016 and 2019 (see Table 1 ). Researches on the topic started being published in a considerable amount from 2009–2010, following the beginning of the crisis. Studies published in the 1990′s refer to previous financial crises, such as the one that took place between the 1970′s and the 1980′s, or even crises in previous centuries.

Studies addressing the Spanish financial crisis published in Scopus up from 2009

Bold indicates years with the highest number of articles

Scientific studies were also subjected to a content analysis, which considered their tittles, abstracts and keywords. Qualitative content analysis is a method for analyzing text data and delve into their meaning by following systematic procedures (Schreier 2012 ). The term includes a series of different techniques to analyse texts (Powers et al. 2010 ). More specifically, content analysis serves to “identify, analyse and inform patterns within the data” (Braun and Clarke 2006 p. 79). It includes the codification and classification of textual units, which makes it very useful to explore big volumes of textual information and determine tendencies, patterns within the words employed, as well as relationships between their meanings (Gbrich 2007 ). Qualitative analysis methods are not only a useful tool for generating knowledge, but also an effective vehicle for presenting and addressing meanings and findings (Holloway and Todres 2005 ; Sandelowski 2010 ). To assure these methods’ validities, researchers must clearly explain how the results were achieved (Schreier 2012 ). In the case of content analysis, the preparation phase starts with the definition of the unit of analysis (Guthrie et al. 2004 ), to which researches must consider what they want to analyse (Cavanagh 1997 ).

In the present investigation, the object of analysis was the academics’ interest in the subject of the Spanish financial crisis. In this context, the units of analysis were, as previously stated, the tittles, abstracts and keywords of scientific studies on this topic. Content analysis may serve two main functions, the heuristic and the proofing function (Bardin 2000 ). Naturally, the goal of the present study was not verifying any previously proposed hypothesis about the interest of academics in the Spanish financial crisis, but simply exploring the trends and patterns in such interest through the analysis of published researches. Therefore, within this investigation, the content analysis serves the heuristic function, as it enriches the exploratory attempt, increasing the likeliness of discovery. Moreover, within the available content analysis techniques, the one adopted in the present study was the categorical content analysis, which consists in dismembering text units, or categories, according to pre-established criteria. In this context, the chosen registry of unit was the word—rather than the theme—which facilitated the systematic analysis of a big volume of texts. Moreover, the main enumeration rule for coding, as it considers that the registry unit’s relevance increases with its frequency of appearance. A quantitative summary of the content analysis’ results is presented in Table 1 .

Web Searches

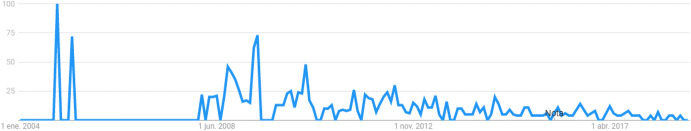

The Google Trends analysis indicated that searches for “crisis financiera española” were only made in Spain. Some related searched topics include “crisis”, “crisis financiera”, “finanzas”, “España” and “ciencia económica”, which showed a consisted increase in searches from 2008. The terms also show two punctual peaks in searches in November 2004 and March 2005, which were indeed the highest search rates within the analysed period. These peaks are followed by April 2009 and September 2008 (Fig. 1 ).

Number of searches for “crisis financiera Española” throughout time (2004–2019)

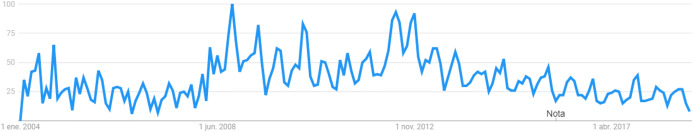

When considering searches for more generic terms, such as “crisis española”, the number of countries from which searches were made increases. Among the additional countries, the ones with the highest numbers are Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Argentina (all Spanish speaking countries) (Fig. 2 ). Related search terms include “crisis económica española”, “la crisis económica”, “crisis económica España”, “crisis política española” and “la economía española” all of which had a puntual increase in searches in 2008, and then consistently decreased, especially after 2014. For these terms, search peaks took place in September 2008, June 2012, November 2012, and May 2010 (Fig. 3 ).

Countries from which searches for “crisis Española” were made (2004–2019)

Number of searches for “crisis española” throughout time (2004–2019)

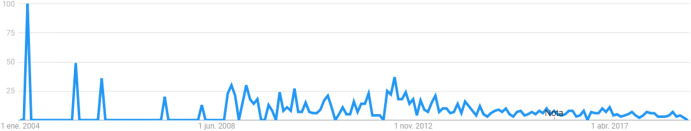

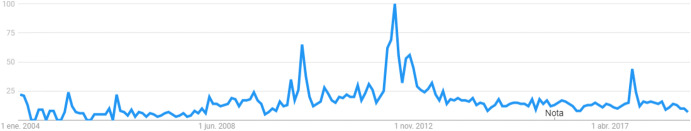

When considering the English term “Spanish financial crisis”, the peak in searches was in March 2004, followed by April 2005 and June 2012. Up from 2014, the numbers decrease significantly (Fig. 4 ). Related search terms that present a punctual increase include “Spain financial crisis” and “Spanish Economic crisis”. When considering searches for the more generic term “Spanish crisis”, the countries from which the most searches were made are Spain, Singapore, United Kingdom, Australia, Nigeria and United States (Fig. 5 ). Searches for this term had their peak in June 2012, followed by May 2010, and unlike in the previous cases, October 2017, which is particularly recent (Fig. 6 ).

Number of searches for “Spanish Financial crisis” throughout time (2004–2019)

Countries from which searches for “Spanish crisis” were made (2004–2019)

Number of searches for “Spanish crisis” throughout time (2004–2019)

Academic Research

As mentioned in the methodology chapter, the search for papers published on Scopus’s database ensued 632 studies addressing the Spanish financial crises since 1990, 96% of which have been published in the last decade. Studies on the subject come from three main areas: Social Sciences (46.2%), Economy, Econometry, and Finances (32.3%), and Business, Management, and Accounting (30.7%)—it must be observed that the same paper can be classified into more than one area. Most of the researches were published on journal papers (83.1%). The remaining documents include reviews (6.9%), book chapters (5.7%), and conference papers (2.1%). To delve deeper into the topic, it is important to know which items are more often addressed within these studies. To this end, a frequency analysis of the whole sample of keywords (n = 1,643) was carried out. Results indicate that the most frequent research topics are Spain, financial crisis, economic crisis, crisis, human, article, economic recession, and finances (Table 2 ).

Top 20 keywords used in studies addressing the Spanish financial crisis (n = 1643)

To analyse the topic even further, the works of the most proliferous authors in the field—Kapelko, M., Lara-Rubio, J., Navarro-Galera, A. and Perles-Ribes, J.F.—were analysed. Each of these authors published five studies within the last 5 years. The titles, abstracts and keywords of such studies were subjected to a content analysis (Table 3 ). Results show that although the crisis took place over a decade ago, back in 2007/2008, it still attracts significant academic interest. Moreover, this interest comes from different research areas, as the mentioned authors investigate areas as distinct as the public sector, the banking sector, the construction industry, and the tourism industry. The concepts analysed within those studies include inefficiency, financial sustainability, and all the effects of the economic and financial crisis worldwide, in the euro zone, and especially in Spain.

Academic studies from the most proliferous authors on the Spanish Financial crisis

The construction industry was one of the most affected, as it depends on economic cycles. Therefore, the situation initiated in 2007 has led to a significant drop in productivity. The country’s economic situation had a great impact on the sector. On the other hand, part of the studies analysed focus on the public sector. These studies emphasize the need for financial transparency, especially on official websites. The solvency problems, risk premiums, and bank loans brought about by the financial crisis ultimately affected local governments, which must deal with the consequent increase in levels of (public) debt. The banking sector is also one of the most affected by the economic situation. One of the biggest problems for the sector is the risk of loyalty loss and abandonment by its clients.

At last, studies analyse how this situation affects one of the star industries of the country: tourism. More specifically, they examined which types of tourist destinations (e.g., seaside, cities, etc.) have already overcome the crisis, as well as how the economic cycles have affected the tourism industry, namely its employment growth rates, since the beginning of the crisis (2007/2008). Studies also examined the opposite effect, that is, how tourism development affects the crisis, specially through the sale of vacation houses, which ultimately affects the construction industry.

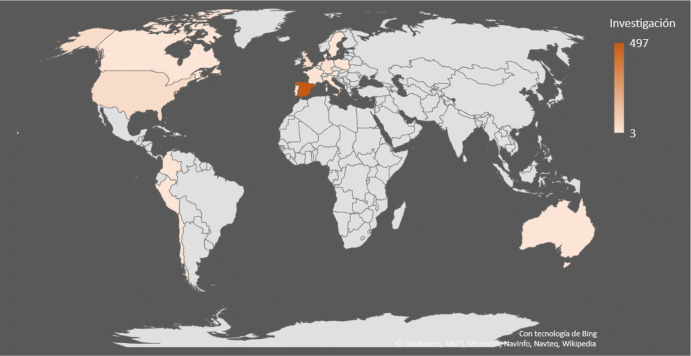

Finally, analogous to the analysis carried out with the web searches, the published papers’ origins were examined and the countries that show the greatest scientific interest in this topic were identified. As expected, the country from which the highest number of studies was published is Spain, which accounts for 78.4% of studies. With significantly lower numbers, the following countries account for most of the remaining researches: United Kingdom (5.8%), United States (5.7%), Germany (3.0%), Italy (2,2%), Netherlands (1.7%), Portugal (1.6%), France (1.4%), and Poland (1.1%). Next, with less than 1% each, comes Sweden, Australia, Canada, Chile, Peru, Austria, Belgium, Colombia, and Denmark (Fig. 7 ).

Countries that investigate the Spanish financial crisis

In the beginning of the twenty-first century, a series of economic circumstances triggered a global economic-financial crisis. These circumstances included the contrast between countries with extreme deficits in their commercial balances and those enjoying atypical surplus values. In Europe, one of the countries that suffered the most as a result of the crisis was Spain. In the years preceding the beginning of the crisis, the country experienced several favourable economic circumstances, such as a higher GDP growth than that of global leaders, i.e., the United States, which eventually proved to be an illusion. In 2007, the economic boom came to an end, following the solvency crisis in the banking system and the decrease in the demand for products and services, especially houses. In this context, the construction industry was one of the most affected, and arguably one of the main factors responsible for amplifying the crisis effects in the country (due to the real estate bubble).

To the present day, Spain has not fully recovered, and the aftermath of the crisis still worries its population. It is particularly striking that, in the years preceding the crisis, there was already an uneasiness about it. This is evidenced by web searches on the topic, which begin to increase already in 2004. In fact, the peak in searches for “crisis financiera española” took place in November 2004, which was an omen of what was about to happen. Moreover, searches related to the Spanish economic crisis, Spanish economy or simply the economic crisis have also been quite frequent, which indicates that the population is still worried and interested in this topic. Once the crisis begins, peaks in searches are once again observed, especially between 2008 and 2012.

When considering searches worldwide (for terms in English), the data shows that the interest in the topic starts decreasing in 2014. Therefore, the peaks in interest from the general internet users take place in two specific moments: years before 2007, when some people already inferred that a crisis was about to come, and the first years of crisis. It must be observed, as well, that although the topic is particularly related to one country, Spain (which is evidenced by the fact that the majority of searches were made from this country), the analysis of searches in English shows that internet users from other countries are also interested in the situation. Those include several European countries, such as United Kingdom (in second place, immediately after Spain), Germany, Italy, Portugal, and France; but also countries from other continents, such as the United States (in third place), and with a significantly lower volume in searches, Australia, Canada, Chile, Peru, and Colombia.

Regarding the academic world, the subject starts attracting a great deal of interest up from 2009/2010, when the crisis had already begun. The peak in number of published papers takes place in 2017 (114 works). However, the biggest growth is noticed between 2011 and 2013, when the number of studies practically doubled. In sum, academic studies show a continuous growth from 2011 to 2017. The most frequently addressed topics amongst the 632 analysed studies are the economic or financial crisis, the economic recession, unemployment, and the banking system. Many studies share some of the same keywords, from which “Spain” is by far the most frequent.

The content analysis carried out on the works from the most proliferous authors within the topic indicates that construction is amongst the most addressed industries or sectors in researches related to the crisis. This is in line with previous literature on the subject, as addressed on the theoretical overview, the construction industry played a relevant role in amplifying the crisis’ effects in Spain and was also one of the most affected economic activities. Other particularly affected area was the public sector, which was also one of the leading figures of the situation, due to the lack of a proactive attitude and preventive measures, and to its actions during the actual crisis. Other authors focus on tourism, a key industry to the Spanish economy, and one that was also affected by the crisis.

Finally, similarly to the general internet user’s interest, academic interest in this subject does not come exclusively from Spain, but also from other European countries, such as Germany, Italy, France, and Portugal. Moreover, studies also come from countries outside Europe, such as the United States, Peru, and Chile. This data indicates that there is a coincidence regarding the countries that show high levels of social preoccupation on the subject, demonstrated by the web searches, and those that show particularly high academic interest.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Adrian, T., & Shin, H. S. (2008). Liquidity and financial cycles. BIS Working Papers, no. 256, july.

- Alcaraz-Quiles FJ, Navarro-Galera A, Ortiz-Rodriguez D. Transparency about sustainability in regional governments: The case of Spain. Convergencia-Revista de ciencias sociales. 2017;73:113–140. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alonso-Almeida M, Bremser K. Strategic responses of the Spanish hospitality sector to the financial crisis. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2013;32:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.05.004. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Álvarez JA. La banca española ante la actual crisis financiera. Estabilidad financiera. 2008;15:23–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Andalial RC, LabradaII RR, Castells MM. Scopus: la mayor base de datos de literatura científica arbitrada al alcance de los países subdesarrollados. Revista Cubana de Información en Ciencias de la Salud (ACIMED) 2010;21(3):270–282. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bardin L. Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bosman, J., Mourik, I. V., Rasch, M., Sieverts, E., & Verhoeff, H. (2006). Scopus reviewed and compared: The coverage and functionality of the citation database Scopus, including comparisons with Web of Science and Google Scholar.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carbó-Valverde, S., Maqui Lopez, E., & Rodríguez-Fernández, F. (2013). Trust in banks: Evidence from the Spanish financial crisis.

- Case, K. E., Shiller, R. J., & Thompson, A. (2012). What have they been thinking? Home buyer behavior in hot and cold markets (No. w18400). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Cavanagh S. Content analysis: Concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Researcher. 1997;4(3):5–16. doi: 10.7748/nr.4.3.5.s2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- eBizMBA. (2018). EBizMBA Rank . https://www.ebizmba.com/articles/search-engines .

- EU-KLEM. (2013). https://www.euklems.net/ .

- García MÁ. Challenges of the construction sector in the global economy and the knowledge society. International Journal of Strategic Property Management. 2005;9(2):65–77. doi: 10.3846/1648715X.2005.9637528. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- García M. The breakdown of the Spanish urban growth model: Social and territorial effects of the global crisis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2010;34(4):967–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.01015.x. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- García-Montalvo J. Deconstruyendo la burbuja: expectativas de revalorización y precio de la vivienda en España. Papeles de economía española. 2006;109:44–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gbrich C. Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. 1. London: Sage Publications; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guthrie J, Petty R, Yongvanich K, Ricceri F. Using content analysis as a research method to inquire into intellectual capital reporting. Journal of intellectual capital. 2004;5(2):282–293. doi: 10.1108/14691930410533704. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holloway, I., & Todres, L. (2005). The status of method. In Qualitative Research in Health Care (pp. 90–102). Open University Press, Maidenhead.

- Kapelko M. Measuring inefficiency for specific inputs using data envelopment analysis: Evidence from construction industry in Spain and Portugal. Central European Journal of Operations Research. 2018;26(1):43–66. doi: 10.1007/s10100-017-0473-z. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kapelko M, Abbott M. Productivity growth and business cycles: Case study of the Spanish construction industry. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management. 2016;143(5):05016026. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001238. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kapelko M, Lansink AO, Stefanou SE. Assessing dynamic inefficiency of the Spanish construction sector pre-and post-financial crisis. European Journal of Operational Research. 2014;237(1):349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2014.01.047. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kapelko M, Oude Lansink A. Technical efficiency and its determinants in the Spanish construction sector pre-and post-financial crisis. International Journal of Strategic Property Management. 2015;19(1):96–109. doi: 10.3846/1648715X.2014.973924. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kapelko M, Oude Lansink A, Stefanou SE. The impact of the 2008 financial crisis on dynamic productivity growth of the Spanish food manufacturing industry. An impulse response analysis. Agricultural Economics. 2017;48(5):561–571. doi: 10.1111/agec.12357. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lara-Rubio, J., Martínez-Fiestas, M., & Cortés-Romero, A. M. (2015). Drop-out risk measurement of E-banking customers. In Banking, finance, and accounting: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (pp. 330–349). IGI Global.

- Lara-Rubio J, Rayo-Cantón S, Navarro-Galera A, Buendia-Carrillo D. Analysing credit risk in large local governments: An empirical study in Spain. Local Government Studies. 2017;43(2):194–217. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2016.1261700. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maldonado JL, Pérez MD. Transformaciones económicas y segregación social en Madrid. Ciudad y territorio. Estudios territoriales. 2008;158:703. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mayer C, Pence K, Sherlund SM. The rise in mortgage defaults. Journal of Economic perspectives. 2009;23(1):27–50. doi: 10.1257/jep.23.1.27. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Montalvo JG. Crisis financiera, reacción regulatoria y el futuro de la banca en España. Estudios de economía aplicada. 2014;32(2):2–32. [ Google Scholar ]

- Navarro-Galera A, Buendía-Carrillo D, Lara-Rubio J, Rayo-Cantón S. Do political factors affect the risk of local government default? Recent evidence from Spain. Lex Localis. 2017;15(1):43. doi: 10.4335/15.1.43-66(2017). [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Navarro-Galera A, Lara-Rubio J, Buendía-Carrillo D, Rayo-Cantón S. What can increase the default risk in local governments? International Review of Administrative Sciences. 2017;83(2):397–419. doi: 10.1177/0020852315586308. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perles-Ribes JF, Ramón-Rodríguez AB, Moreno-Izquierdo L, Sevilla-Jiménez M. Economic crises and market performance—A machine learning approach. Tourism Economics. 2017;23(3):692–696. doi: 10.5367/te.2015.0536. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perles-Ribes JF, Ramón-Rodríguez AB, Rubia-Serrano A, Moreno-Izquierdo L. Economic crisis and tourism competitiveness in Spain: Permanent effects or transitory shocks? Current Issues in Tourism. 2016;19(12):1210–1234. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2013.849666. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perles-Ribes JF, Ramón-Rodríguez AB, Rubia A, Moreno-Izquierdo L. Is the tourism-led growth hypothesis valid after the global economic and financial crisis? The case of Spain 1957–2014. Tourism Management. 2017;61:96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.003. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perles-Ribes JF, Ramón-Rodríguez AB, Sevilla-Jiménez M, Moreno-Izquierdo L. Unemployment effects of economic crises on hotel and residential tourism destinations: The case of Spain. Tourism Management. 2016;54:356–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.12.002. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perles-Ribes JF, Ramón-Rodríguez A, Vera-Rebollo JF, Ivars-Baidal J. The end of growth in residential tourism destinations: steady state or sustainable development? The case of Calpe. Current Issues in Tourism. 2018;21(12):1355–1385. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2016.1276522. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Powers BA, Knapp T, Knapp TR. Dictionary of nursing theory and research. Berlin: Springer; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Royo S. After the fiesta: The Spanish economy meets the global financial crisis. South European Society and Politics. 2009;14(1):19–34. doi: 10.1080/13608740902995828. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Royo S. How did the Spanish Financial System survive the first stage of the global crisis? Governance. 2013;26(4):631–656. doi: 10.1111/gove.12000. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in nursing & health. 2010;33(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schreier M. Qualitative content analysis in practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stiglitz JE. Freefall: America, free markets, and the sinking of the world economy. New York: WW Norton & Company; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Taylor, J. B. (2009). The financial crisis and the policy responses: An empirical analysis of what went wrong (No. w14631). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Vergés R. The information asymmetry in the Spanish real estate sector. Crisis and stocks. Observatorio inmobiliario y de la construcción. 2011;48:52–59. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (901.3 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Enable JavaScript in your browser to view this website correctly.

Close panel

- Publications

- Reading lists

- Add to "Read later"

- Eliminar de "Leer más tarde"

- Add to "My library"

- Eliminar de "Mi biblioteca"

- Share on Facebook

- Share on X (Twitter)

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on WhatsApp

- Share on Telegram

Spain | DANA: Real-time monitoring of the economic impact

See social media to share

- X (Twitter)

Close social media to share

See tools to share

Close tools to share

Published on Friday, November 29, 2024

Big Data techniques used

Spending in the province of Valencia rebounded during the week of November 19 to 25. The growth differential with the rest of Spain became positive in most indicators, although the most affected municipalities still show significant falls.

- Key points:

- In-person spending in the province of Valencia was reactivated three weeks after DANA. It increased 3.1% year-on-year, above what was observed in the previous week (0.3%). The difference in variation with the rest of Spain was positive for the first time since the flood (1.6 pp).

- Strong dynamism was observed especially in purchases with Spanish cards, which grew by 3.8% year-on-year in the week ending November 25. Timid signs of improvement are also beginning to be observed in spending with foreign cards, whose negative gap with respect to the rest of the country narrowed to -17 pp.

- The improvement in spending was widespread by sector. Almost all of them closed the growth differential with respect to the rest of Spain. The rebound was particularly intense in some activities related to tourism (travel, accommodation, transportation and leisure), as well as automotive, books and press and fashion.

- The recovery intensifies and begins to be more evident, especially in the weekly variation. Among the most affected municipalities, the pace of recovery is beginning to accelerate in some of them, while the most affected continue to stagnate.

Documents to download

Presentation (pdf).

- BBVA Research BBVA Research

Geographies

- Geography Tags

- Valencian Community

- Macroeconomic Analysis

- Regional Analysis Spain

- Consumption

- Climate Sustainability

- Climate change

- Climate risks

- Cards expenditures

- Data Analytics

- Sectoral and Digital Economy Analysis & Industrial Organization

- Regional & Urban Economics

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

Was this information useful?

- I found it useful

- I did not find it useful

New comment

Be the first to add a comment.

You may also be interested in

Post your comment.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Economic Research Portal is directed towards the community of economic and financial researchers worldwide, to provide quick access to publications, statistics, and other information of interest relating to the research output of the Banco de España.

The Quarterly report and macroeconomic projections for the Spanish economy series analyses recent developments in the economy, in the international and euro area context, and updates the Banco de España’s projections for the Spanish economy for the current year and the following two years.

The aim of the Working Papers series is to disseminate research papers on economics and finances by Banco de España researchers. The Working Papers are published once they have successfully come through an anonymous evaluation process.

Spain has improved particularly in gender equality, quality of education, and climate action. However, it still needs to catch up with the EU average on several SDGs, particularly on no poverty, decent work and economic growth, and reduced inequalities. Moreover, Spain is falling back from the target on

The snapshot offers a concise summary of Spain's economic trends and prospects, drawing from the OECD Economic Survey, Economic Outlook, and Economic Policy Reform: Going for Growth reports, delivering in-depth analyses of economic trends, suggested policy recommendations, alongside an overview of structural policy developments.

The present work analyses the interest demonstrated by both the general population and economic scholars (and those from related areas) in the economic-financial crisis that affected Spain up until the observed period (2019).

OECD’s periodic surveys of the Spanish economy. Each edition surveys the major challenges faced by the country, evaluates the short-term outlook, and makes specific policy recommendations. Special chapters take a more detailed look at specific challenges.

This Observatory assesses the factors explaining the behavior of the Spanish economy between the first quarter of 2020 and the last quarter of 2021, and estimates the structural shocks behind the growth of GDP per working-age person (WAP), the GDP deflator and real wages.

The difference in variation with the rest of Spain was positive for the first time since the flood (1.6 pp). Strong dynamism was observed especially in purchases with Spanish cards, which grew by 3.8% year-on-year in the week ending November 25.

We examine the impacts of fiscal policy on economic activity in Spain. • We assess short- and long-run symmetric and asymmetric effects of fiscal policy. • We offer estimates both for aggregated and disaggregated public expenditures and net revenues. •