Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Research Funded by NIMH

Research conducted at nimh (intramural research program), priority research areas.

- Research Resources

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), is the lead federal agency for research on mental disorders, supporting research that aims to transform the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses through basic and clinical research. Learn more about NIMH-funded research areas, policies, resources, initiatives, and research conducted by NIMH.

Notify the NIMH Press Team about NIMH-funded research that has been submitted to a journal for publication, and we may be able to promote the findings.

NIMH Strategic Plan

The NIMH Strategic Plan for Research outlines the Institute's research goals and priorities over the next five years. Learn more about the Strategic Plan.

NIMH supports research at universities, medical centers, and other institutions via grants, contracts, and cooperative agreements. Learn more about NIMH research areas, policies, resources, and initiatives:

- Research Domain Criteria (RDoC)

- Policies and Procedures

- Inside NIMH - Funding and Research News

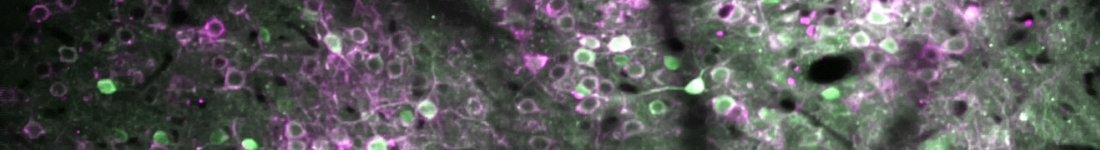

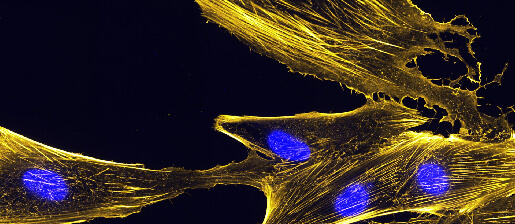

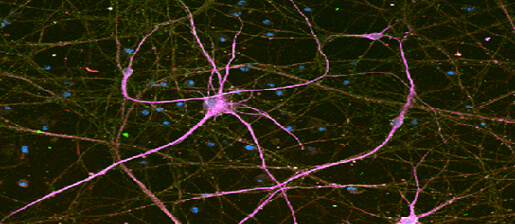

The Division of Intramural Research Programs (IRP) is the internal research division of the NIMH. Over 40 research groups conduct basic neuroscience research and clinical investigations of mental illnesses, brain function, and behavior at the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland. Learn more about research conducted at NIMH:

- Intramural Investigators

- Intramural Research Groups

- Fellowships and Training

- Office of the Scientific Director

- Collaborations and Partnerships

- Join a Study

- IRP News and Events

- NIMH Priority Research Areas

- Highlighted Research Initiatives

Resources for Researchers

- Psychosocial Research at NIMH: A Primer

- Genomics Research Guidance for Grant Applicants

NIMH Women Leading Mental Health Research

Diversity in the scientific workforce enhances excellence, creativity, and innovation. NIMH and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are committed to increasing diversity in the scientific workforce. Learn more about early-career women scientists whose NIMH-funded research is playing a role in advancing our mission of transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

- Vision, Mission and Purpose

- Focus & Scope

- Editorial Info

- Open Access Policy

- Editing Services

- Article Outreach

- Why with us

- Focused Topics

- Manuscript Guidelines

- Ethics & Disclosures

- What happens next to your Submission

- Submission Link

- Special Issues

- Latest Articles

- All Articles

Childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A meta-analysis

Marcelo Nvo-Fernández 1* , Valentina Miño-Reyes 1 , Gastón González-Cabeza 2 , Sofia Gálvez-Cienfuegos 1 , Martina Ignacia C.C 2 1 Laboratory of Methodology, Behavioural Sciences and Neuroscience, Faculty of Psychology, Universidad de Talca, Talca, Chile 2 Universidad Autónoma de Chile, Talca, Chile

Sexual abuse, especially when it occurs during childhood, is an experience that causes deep and lasting harm. Currently, its study as a risk factor for the development of trauma-related pathologies is of great relevance. In 2018, Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) was officially recognized as a distinct syndrome in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), with the aim of distinguishing it from neurotic disorders secondary to stressful situations, somatoform disorders, and those specifically associated with stress. The inclusion of CPTSD in the ICD-11 marked the culmination of two decades of research dedicated to understanding its symptoms, treatments, and risk factors. This article aims to conduct a meta-analysis that explores the relationship between sexual abuse and the development of CPTSD. Fifteen studies were selected for analysis, and the results revealed several key risk factors associated with the development of CPTSD, with the primary one being childhood sexual abuse (k = 15; OR = 3.007).

Mood Disorders and Rapid Screening: A Brief Review

Helene Vossos 1* , Ozioma Nwosu-Izevbekhai 2 1 Associate Professor of Nursing, PMHNP Program Coordinator, University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, St. Augustine, Florida, USA 2 Assistant Professor in Residence, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, USA

Objective: The purpose of this manuscript is for readers to understand the differences between bipolar and unipolar mood disorders. Readers will be able to apply evidence-based screening tools to differentiate in the diagnosis of bipolar versus unipolar depressive disorders. The goal is to increase diagnostic accuracy of mood disorders with the opportunity to provide treatment that will lead to improved patient outcomes.

Method: Review of literature discovered 13 articles that were pertinent with three major themes. One theme showed up to 62% of bipolar disorder cases were missed or undiagnosed upon the first evaluation, second theme showed 7% to 70% of individuals were misdiagnosed with adverse outcomes and third theme discovered the importance of specialty psychiatric training, education and the use of evidence-based screening tools combined with clinical judgement improved the accuracy of the correct mood disorder diagnosis.

Findings: In mood disorders, if left untreated or misdiagnosis occurs, the risk of suicide is higher (29.2%) in bipolar affective disorder, versus unipolar major depressive disorder (17.3%).

Implications for clinical practice: Recommendation for the use of evidence-based screening tools are clinical best practices for screening and diagnosing bipolar affective disorders with a statistical significance of 95%. Misdiagnosis is common up to 70% and the implications of timely rapid assessments allow for prompt interventions that has shown to halt and/or prevent mental health conditions to worsen, reducing risk of emergency situations.

Adolescents' Participation in Drug Addiction Interventions, Individual Perceptions, and Attitudes towards Recovery: A Scoping Review

Anthony Ezerioha 1 , Masoud Mohammadnezhad 2* 1 School of Allied Health and Social Care, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Social Care, Angelia Ruskin University, Cambridge, UK 2 Faculty of Health, Education and Life Sciences, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Birmingham City University, Birmingham, UK

Introduction : Adolescents recovering from substance use problems face significant psycho-social challenges. These challenges can affect their recovery progress, overall well-being, and integration into the society. Due to paucity studies, this study aimed to identify the perceptions and attitude towards recovery among adolescents participating in drug addiction interventions.

Methods : This systematic review study applied a complete search of relevant databases, including Scopus, Embase, Cinahl, and PubMed/Medline using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The search was limited to articles published in English language, between 2013 and 2023, and focused on adolescents drug addiction. Twelve articles were critically appraised using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) for qualitative studies and Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tools. The results were synthesised using a thematic analysis.

Results: The findings identify that adolescents in addiction recovery face several challenges, including stigmatisation, social isolation, self-doubt, and difficulties accessing and maintaining treatment. The findings also point out that supportive relationships, culturally sensitive treatment approaches and interventions to combat self-stigma can play a critical role in promoting resilience and recovery for adolescents in recovery.

Conclusion : The comprehensive review brings us up to speed on the challenging experiences young people recovering from addiction in different addiction intervention go through, it underscores the importance of supportive relationships and encourages strengthening of interventions that mitigate against stigmatization.

Tele-Psychiatry to Address Severe Persistent Mental Illness in Rural Communities: An Economic and Break-Even Analysis

Sarah C. Haynes 1,2* , James P. Marcin 1,2 , Peter Yellowlees 3 , Stephanie Yang 1 , Jeffrey S. Hoch 4,5 1 Department of Pediatrics, University of California Davis, Sacramento, California, USA 2 Center for Health and Technology, University of California Davis, Sacramento, California, USA 3 Department of Psychiatry, University of California Davis, Sacramento, California, USA 4 Department of Public Health Sciences, University of California Davis, Sacramento, California, USA 5 Center for Healthcare Policy and Research, University of California Davis, Sacramento, California, USA

Background: People living in rural communities experience significant barriers accessing mental health care, including a shortage of psychiatrists and other behavioral health specialists. Telemedicine has the ability to improve access for these populations by allowing psychiatrists in urban settings to treat rural patients over video. However, start-up costs may hinder implementation of new tele-psychiatry programs.

Materials and Methods: We created a model to estimate the point at which tele-psychiatry would financially break even based on estimates of improved access to outpatient care for people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. We demonstrate how our model can be used with an example of a tele-psychiatry program serving five rural Indian Health Services clinics in California.

Results: When reimbursement for psychiatric services provided over telemedicine is relatively low compared to reimbursement for hospitalization visits, changes in the ratio of hospitalizations to telemedicine visits have very little impact on required hospitalization improvement.

Conclusions: Tele-psychiatry programs are likely to break even within the first three years when providing psychiatry services to a rural community with a scarcity of mental health services. Our findings are important because they indicate that the cost of improving access to tele-psychiatry services is likely low compared to the potential cost savings associated with reduced hospitalizations for people with severe persistent mental illness.

Barriers and Solutions to Comprehensive Care for Mental Health Patients in Hospital Emergency Departments

Elizabeth Levin 1* , Husam Aburub 2 1 Department of Psychology, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada 2 Health Sciences North, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada

Hospital emergency departments in Ontario, have become a common place for patients with mental health problems to seek treatment. Studies report healthcare providers have limited knowledge and competency to provide optimal care for patients with mental health problems. As a result, these patients are at risk of poor hospital experiences and treatment outcomes. In addition, emergency staff report considering patients with mental health problems lower priority to other patients. This paper reviews the existing literature and examines the challenges surrounding patients with mental health problems seeking treatment in emergency rooms and how it leads to sub-optimal care. Strategies are then shared to overcome these challenges by changing emergency department experiences for mental health patients seeking treatment.

Effects of Interpersonal Psychotherapy on Postpartum Depression among Females at Tertiary Care Hospital Lahore

Sehrish Arshad 1* , Muhammad Afzal 2 , Hajra Sarwar 3 1 Doctors Hospital College of Nursing and Allied Health Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan 2 Director Academics Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Lahore, Pakistan 3 University of Lahore, Pakistan

Introduction: Postpartum depression (PPD) is a major public health issue among females after giving birth to the baby, characterized by low mood, feeling of guilt and suicide. When left untreated, it has the potential for a profound negative impact on mothers, children and families. The efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) in addressing depression has been well-documented. However, the impact of IPT on PPD remains inadequately substantiated, particularly within the context of Pakistan, where data pertaining to its effectiveness remains limited.

Objective: The aim of study was to assess the level of depression in postpartum females and evaluate the effects of IPT on PPD among females at tertiary care hospital Lahore.

Methods: A Randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted at the Services Hospital Lahore from September 2021 to the same month in 2023. Subjects (n=110) were screened using the hamilton depression rating scale (HDRS) and divided equally in intervention group and control group to get eight sessions of individual based IPT versus routine care. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 21, intergroup comparison was done by Mann Whitney U test for intra group comparison Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was used, with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and 5% level of significance. Significance of result showed with p value <0.05.

Results: Prevalence of PPD among female was observed 82%. Upon receiving IPT, females exhibited a statistically significant reduction (p<0.001) in scores indicative of mild depression, from 48 (87.3%) to 5(9.1%), as well as for moderate depression, from 7(12.7%) to 1(1.8%). Furthermore, following the IPT sessions, marked improvements were noted within the intervention group across various domains including depressed mood p<0.001, CI (0.000, 0.027), feelings of guilt p<0.001, CI (0.000, 0.027), early night insomnia p<0.008, CI (0.000, 0.043), impaired work and activities p<0.05, CI (0.072, 0.200), and insight p<0.001, CI (0.000, 0.027). Conversely, the control group did not exhibit any significant alterations in these parameters.

Conclusion: The results indicate a concerning prevalence rate of PPD among the study sample with many cases remaining undiagnosed and untreated. More positively, the study demonstrates the potential of IPT as an effective method to mitigate mild to moderate PPD. This research suggests the incorporation of IPT into therapeutic models could result in timely, potentially preventive interventions and lessen the occurrence of severe complications.

Sex Differences in the Relationship Between Nucleus Accumbens Volume and Youth Tobacco or Marijuana Use Following Stressful Life Events

Shervin Assari 1,2,3 *, Payam Sheikhattari 4,5,6 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2 Department of Family Medicine, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 3 Department of Urban Public Health, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 4 Center for Urban Health Disparities Research and Innovation, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD, USA 5 The Prevention Sciences Research Center, School of Community Health and Policy, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD, USA 6 Department of Public and Allied Health Sciences, School of Community Health and Policy, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD, USA

Background: Exposure to stressful life events (SLEs) can upset balance and affect the healthy brain development of children and youths. These events may influence substance use by altering brain reward systems, especially the nucleus accumbens (NAc), which plays a key role in motivated behaviors and reward processing. The interaction between sensitization to SLEs, depression, and substance use might vary between male and female youths, potentially due to differences in how each sex responds to SLEs.

Aims: This study aims to examine the effect of sex on the relationship between SLEs, Nucleus Accumbens activity, and substance use in a nationwide sample of young individuals.

Methods: We utilized data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study (ABCD), a longitudinal study of pre-adolescents aged 9–10 years, comprising 11,795 participants tracked over 36 months. Structured interviews measuring SLEs were conducted using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS). Initial linear regression analyses explored if SLEs could predict volumes of the right and left NAc. Subsequently, Cox regression models were used to investigate how SLEs and NAc volume might predict the initiation of tobacco and marijuana use, with the analysis stratified by sex to address potential sex differences.

Results: Our findings reveal that SLEs significantly predicted marijuana use in males but not in females, and tobacco use was influenced by SLEs in both sexes. A higher number of SLEs was linked with decreased left NAc volume in males, a trend not seen in females. The right NAc volume did not predict substance use in either sex. However, volumes of both the right and left NAc were significant predictors of future tobacco use, with varying relationships across sexes. In females, an inverse relationship was observed between both NAc volumes and the risk of tobacco use. In contrast, a positive correlation existed between the left NAc volume and tobacco and marijuana use in males, with no such relationship for females.

Conclusion: This study underscores that the associations between SLEs, NAc volume, and subsequent substance use are influenced by a nuanced interplay of sex, brain hemisphere, and substance type.

What is Common Becomes Normal; Black-White Variation in the Effects of Adversities on Subsequent Initiation of Tobacco and Marijuana During Transitioning into Adolescence

Shervin Assari 1,2* , Babak Najand 3 , Payam Sheikhattari 4,5,6 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2 Department of Urban Public Health, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 3 Marginalization-related Diminished Returns Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA 4 Center for Urban Health Disparities Research and Innovation, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD, USA 5 The Prevention Sciences Research Center, School of Community Health and Policy, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD, USA 6 Department of Behavioral Health Science, School of Community Health and Policy, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD, USA

Background: While adversities across domains of finance, race, family, and life may operate as risk factors for initiation of substance use in adolescents, the influence of these factors may vary across racial groups of youth. Unfortunately, the existing knowledge is minimal about racial differences in the types of adversities that may increase the risk of subsequent substance use initiation during the transition into adolescence.

Aim: To compare racial groups for the effects of adversities across domains of finance, race, family, and life on subsequent substance use initiation among pre-adolescents transitioning into adolescence.

Methods: In this longitudinal study, we analyzed data from 6003 non-Latino White and 1562 non-Latino African American 9-10-year-old children transitioning into adolescence. Data came from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. Participants were followed for up to thirty-six months as they transitioned to adolescence. The independent variables were adversities related to the domains of finance, race, family, and life. The primary outcomes were time to first tobacco or marijuana use. Age, puberty, and gender were confounders. Cox regression models were used for data analysis.

Results: For White youth, tobacco use was under influence of having two parents in the household (HR = .611; 95% CI = .419-.891), parental education (HR = .900; 95% CI = .833-.972), household income (HR = .899; 95% CI = .817-.990), racial stress (HR = 1.569; 95% CI = 1.206-2.039), and life stress (HR =1.098 ; 95% CI = 1.024-1.178) and marijuana use was under influence of neighborhood income (HR = .576; 95% CI = .332-.999) and financial stress (HR =4.273; 95% CI = 1.280-17.422). No adverse condition predicted tobacco or marijuana use of African American youth.

Conclusion: The effects of adversities on substance use depend on race. While various types of adversities tend to increase subsequent initiation of tobacco and marijuana, such factors may be less influential for African American adolescents, who experience more of such adversities. What is common may become normal.

Diagnosing Human Trafficking Victims: A Mini-Review and Perspective

Sheldon X. Zhang 1 , Rumi Kato Price 2* 1 School of Criminology and Criminal Justice Studies, University of Massachusetts at Lowell, Lowell, Massachusetts, USA 2 Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, USA

The global campaign against human trafficking, also known as trafficking in persons, has gained much momentum in the past two decades. Although psychiatric and physical illness sequela of human trafficking are well documented, the research community continues to struggle over such foundational questions as what specific activities or experiences count as trafficking-in-persons victimization and how best to obtain representable and generalizable data on experiences of people who are trafficked. We provide a brief review of major efforts to define trafficking in persons to establish prevalence estimates to date. We argue for consensus on key clinical and public health indicators, resembling the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) approach to enable common and systematic knowledge building and comparability across studies.

Immigration, Educational Attainment, and Subjective Health in the United States

Rifath Ara Alam Barsha 1 , Babak Najand 2 , Hossein Zare 3,4 , Shervin Assari 5,6,7* 1 School of Community Health & Policy, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD, USA 2 Marginalization Related Diminished returns, Los Angeles, CA, USA 3 Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA 4 University of Maryland Global Campus, Health Services Management, Adelphi, Maryland, USA 5 Department of Family Medicine, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 6 Department of Internal Medicine, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 7 Department of Urban Public Health, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Objectives: Although educational attainment is a major social determinant of health, according to Marginalization-related Diminished Returns (MDRs), the effect of education tends to be weaker for marginalized groups compared to the privileged groups. While we know more about marginalization due to race and ethnicity, limited information is available on MDRs of educational attainment among US immigrant individuals.

Aims: This study compared immigrant and non-immigrant US adults aged 18 and over for the effects of educational attainment on subjective health (self-rated health; SRH).

Methods: Data came from General Social Survey (GSS) that recruited a nationally representative sample of US adults from 1972 to 2022. Overall, GSS has enrolled 45,043 individuals who were either immigrant (4,247; 9.4%) and non-immigrant (40,796; 90.6%). The independent variable was educational attainment, the dependent variable was SRH (measured with a single item), confounders were age, gender, race, employment and marital status, and moderator was immigration (nativity) status.

Results: Higher educational attainment was associated with higher odds of good SRH (odds ratio OR = 2.08 for 12 years of education, OR = 2.81 for 13-15 years of education, OR = 4.38 for college graduation, and OR = 4.83 for graduate studies). However, we found significant statistical interaction between immigration status and college graduation on SRH, which was indicative of smaller association between college graduation and SRH for immigrant than non-immigrant US adults.

Conclusions: In line with MDRs, the association between educational attainment and SRH was weaker for immigrant than non-immigrant. It is essential to implement two sets of policies to achieve health inequalities among immigrant populations: policies that increase educational attainment of immigrants and those that increase the health returns of educational attainment for immigrants.

Commentary: Black Mothers in Racially Segregated Neighborhoods Embodying Structural Violence: PTSD and Depressive Symptoms on the South Side of Chicago

Loren Henderson 1* , Ruby Mendenhall 2 , Meggan J Lee 3 1 The School of Public Policy, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD, USA 2 Department of Sociology, Department of African American Studies, Carle Illinois College of Medicine, IL, USA 3 Carle Illinois College of Medicine, Urbana, IL, USA

Exposure to Adverse Life Events among Children Transitioning into Adolescence: Intersections of Socioeconomic Position and Race

Shervin Assari 1,2,3* , Babak Najand 4 , Alexandra Donovan 1 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2 Department of Family Medicine, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 3 Department of Urban Public Health, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 4 Marginalization related Diminished Returns Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Background: Racism is shown to diminish the protective effects of family socioeconomic position (SEP) resources for racial minorities compared to the majority groups, a pattern called minorities’ diminished returns. Our existing knowledge is minimal about diminished returns of family SEP indicators on reducing exposure to adverse life events among children transitioning into adolescence. Aim: To compare diverse racial groups for the effects of family income and family structure on exposure to adverse life events of pre-adolescents transitioning to adolescence.

Methods: In this longitudinal study, we analyzed data from 22,538 observations belonging to racially diverse groups of American 9–10-year-old children (n = 11,878) who were followed while transitioning to adolescence. The independent variables were family income and family structure. The primary outcome was the number of stressful life events with impact on adolescents, measured by the Life History semi-structured interview. Mixed-effects regression models were used for data analysis to adjust for data nested to individuals, families, and centers.

Results: Family income and married family structure had an overall inverse association with children’s exposure to adverse life events during transition to adolescence. However, race showed significant interactions with family income and family structure on exposure to adverse life events. The protective effects of family income and married family structure were weaker for African American than White adolescents. The protective effect of family income was also weaker for mixed/other race than White adolescents.

Conclusion: While family SEP is protective against children’s exposure to adverse life events, this effect is weaker for African American and mixed/other race compared to White youth.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Depression Associated with Developmental Prosopagnosia: A Case Report

Kaishi Imatani 1 , Takeshi Inoue 2* , Yuji Oto 1 , Tasuku Kitajima 2 , Ryoko Otani 2 , Satoshi F Nakashima 3 , So Kanazawa 4 , Masami K. Yamaguchi 5 , Ryoichi Sakuta 2 , Tomoyo Matsubara 1 1 Department of Pediatrics, Dokkyo Medical University Saitama Medical Center, Koshigaya, Saitama, Japan 2 Child Development and Psychosomatic Medicine Center, Dokkyo Medical University Saitama Medical Center, Koshigaya, Saitama, Japan 3 Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Human Environments, Okazaki, Aichi, Japan 4 Department of Psychology, Japan Women’s University, Kawasaki, Kanagawa, Japan 5 Department of Psychology, Chuo University, Hachioji, Tokyo, Japan

Developmental prosopagnosia is a disorder of facial recognition that begins during early childhood in the absence of acquired central nervous system disease. We report the case of a 15-year-old female with developmental prosopagnosia as measured by the 20-item Prosopagnosia Index and Cambridge Face Memory Test who ultimately developed generalized anxiety disorder and depression despite relatively normal social and psychological function during early childhood. In elementary school, the case patient adapted by learning alternative ways to identify others, such as by clothing and hairstyle, but this became more difficult in junior high school due to the requirement for school uniforms and regulations on hairstyle. This difficulty in turn led to interpersonal problems that ultimately resulted in symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder and depression, such as headache and sleep dysfunction. People with developmental prosopagnosia are generally prone to having depressed and anxious feelings. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of anxiety disorder or depression related to developmental prosopagnosia. This comorbidity may be relatively common, especially in ethnically homogeneous countries with strict school regulations on personal appearance such as Japan.

Remote Warfare with Intimate Consequences: Psychological Stress in Service Member and Veteran Remotely-Piloted Aircraft (RPA) Personnel

Seth Davin Norrholm 1,2* , Jessica L. Maples-Keller 3 , Barbara O. Rothbaum 3 , Chad C. Tossell 2 1 Neuroscience Center for Anxiety, Stress, and Trauma, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan, USA 2 Department of Behavioral Sciences and Leadership, United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado, USA 3 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

The use of remote piloted aircraft (RPAs) has been a part of military operations for decades and this type of service can present its own unique constellation of combat experiences and psychological consequences. The RPA crewmember experience has typically involved surveillance, targeting, striking, and after-battle assessments of individuals of interest to a host country or agency from a distance that can span several thousand miles. These operators are engaged in physically remote activities that carry a significant degree of intimacy due to the live, high-resolution, high-fidelity images and sounds that are available to the combatants in real-time. The potential psychological consequences of this type of military occupational specialty can include the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as moral injury, mental exhaustion or burnout, and disturbed sleep. The following narrative review examines the current state of RPA warfare from a psychological trauma perspective with an emphasis on the evolution of the inherent technology, the operator force, the psychological experiences and consequences of this type of service, and potential preventative interventions for servicemembers. A key objective of this narrative review is to integrate the available peer-reviewed empirical data, experiential military perspectives and analyses, clinician observations from this unique population, and exemplar reports from those with lived experience on an RPA crew regarding psychological consequences of this military occupational specialty.

Social Anxiety in University Students: Towards an Intentional Life-Skills Based Prevention Model

Hannah Ali * , Steve Joordens Department of Psychology, University of Toronto Scarborough, Toronto, ON, Canada

Research suggests that staying connected with people is very beneficial to our physical and mental well-being. Moreover, a lack of social connection is associated with poor mental and physical health, and lower overall well-being. For individuals with social anxiety, it is particularly difficult to cultivate social connections. Due to the prolonged period of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, research suggests that social anxiety in university students has increased. This study employed a convergent parallel mixed method design and administered a self-reported questionnaire which included quantitative and qualitative questions. The questionnaire was administered to 301 undergraduate students to determine if feelings of social anxiety in students changed during and after the pandemic. This study also analyzed social anxiety levels across racial and ethnocultural demographics and assessed the cultural stigmas and barriers that may prevent students from accessing mental health services. Results from the quantitative analyses showed a significant difference in social anxiety scores before and after the pandemic. However, in our sample, feelings of social anxiety post-pandemic did not differ across race, or income which were our main variables of interest. In addition, there was a positive correlation between social anxiety scores and household income and fear of negative evaluation. The qualitative results showed that important barriers to accessing mental health services include fear of parents learning they are in therapy, cost of mental health services, language barriers, and concern that a therapist would not have cultural sensitivity. This study highlights the need for increased interventions to reduce social anxiety among students, and proposes a preventative approach we refer to as “Life-Skills Training” to address social anxiety.

Mental health clinical exams’ evident adherence to industry standards for testing

Benjamin E. Caldwell California State University Northridge, CA, USA

The developers of clinical exams for US mental health licensure have faced significant recent criticism and calls for their exams to be paused or discontinued. 1,2 Critics cite concerns over exams lacking evidence of validity, while they demonstrate strong evidence of racial and ethnic bias. Developers, in turn, argue that their exams are developed using accepted methods that conform with industry standards, specifically, the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing . 3

This manuscript challenges that assertion. Based on external research as well as developers’ own statements and publications, clinical exams for US mental health care licensure appear to deviate in important ways from both the letter and the spirit of the Standards . Clinical exams should be paused unless and until they are shown to be fair, equitable, valid, and more fully consistent with industry norms.

Adolescent Woes? Approval Motivation, Test Anxiety, and the Role of Perceived Self-Control

Swati Y Bhave * , Jill N Mota, Latika Bhalla, Shailaja Mane, Anuradha Sovani, Surekha Joshi Association of Adolescents and Child Care in India (AACCI), India

The Association of Adolescents and Child Care in India (AACCI) conducts multicentric studies on youth behavior in India. Using openly accessible psychometric tools, the present study discusses the demographic-wise interrelationships between the Children’s Perceived Self-Control (PSC), Martin-Larsen Approval Motivation (AM), and Friedben’s Test Anxiety Scales (FTAS) administered to 712 students (Group-1: 10-14 yrs.; Group-II: 15-18 yrs.) from two Delhi-based schools. The survey-questionnaire included four demographic variables: age, gender, sibling status, and body mass index. Although mainstream literature has uniformly contented in favour of the benefits of PSC, one-way ANOVAs in the present study revealed that high PSC was associated with significantly high AM (F[2,709] =3.033, p =0.049), suggesting that people with high PSC may diligently weigh short- and long-term consequences, choosing behaviors that best align with their interests and enduringly valued goals. Further, this relationship was statistically significant for participants in the no siblings (p =0.005) and underweight groups (p =0.031). Participants with high PSC had the lowest FTAS scores; however, this relationship was not statistically significant. Lastly, AM and FTAS were negatively correlated (r =-0.216, p<0.01), especially for females, Group-II, and participants with siblings (r =-0.278, -0.292, and -0.244, respectively), clarifying distinct differences between AM and FTAS’ subscales. The implications of findings were shared with the school management to conduct customized interventions using the WHO’s Life Skills Education framework. The findings highlight the need for time-series interventional analysis to ascertain the direct and cumulative effects of intervention on the interrelationships between PSC, AM, and FTAS.

Increasing Diversity and Inclusion in Research on Virtual Reality Relaxation: Commentary on ‘Virtual Reality Relaxation for People with Mental Health Conditions: A Systematic Review’

Simon Riches 1,2,3* , Deanna Fallah 3,4 , Ina Kaleva 5 1 Department of Psychology, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College London, London, United Kingdom 2 Social, Genetic & Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College London, London, United Kingdom 3 South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom 4 School of Psychology, University of Surrey, Surrey, United Kingdom 5 Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College London, London, United Kingdom

The Effectiveness of Mentalization-Based Treatment on Mindfulness and Perceived Social Support in Adolescents

Sarah Bagherzadeh Jalilvand * , Sedigheh Ahmadi Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran

Adolescence is a critical period marked by significant changes in social relationships and emotional development. In light of the importance of promoting mental health in this age group, this study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of a mentalization-based treatment intervention on mindfulness and perceived social support among female adolescents aged 12-15 years in Tehran.

A pretest-posttest control group design was employed, with participants randomly assigned to either the intervention group, which received the mentalization-based treatment, or the control group, serving as a comparison for evaluating the intervention's effectiveness. The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Questionnaire (MSPSS) were used to measure mindfulness and perceived social support, respectively.

The mentalization-based treatment intervention focused on enhancing the participants' ability to understand and interpret their own and others' mental states, fostering empathy, and improving interpersonal relationships.

Data analysis was performed using Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) to assess the impact of the mentalization-based treatment on mindfulness and perceived social support in female adolescents. The results indicated a significant improvement in both mindfulness and perceived social support after the intervention (P < 0.01).

In conclusion, the findings suggest that mentalization-based treatment holds promise as an effective approach to enhance mental health outcomes, particularly in promoting mindfulness and perceived social support in female adolescents. Future attention should be given to the implementation of this intervention to support the well-being of adolescents during this critical developmental stage.

Race, Socioeconomic Status, Health Locus of Control, and Body Mass Index

Shervin Assari 1,2,3,4 *, Babak Najand 5 1 Department of Urban Public Health, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2 Department of Family Medicine, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 3 School of Nursing, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 4 Department of Internal Medicine, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA 5 Marginalization-Related-Diminished Returns (MDRs) Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Background: This cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the complex interplay between socioeconomic status (SES), internal and external health locus of control, and body mass index (BMI) in a national sample of US adults. Given the unique challenges faced by Black individuals, it was hypothesized that the relationships between SES, internal and external health locus of control, and BMI would be weaker for Blacks compared to Whites.

Methods: For this cross-sectional study, baseline data from the MIDUS Refresher sample, consisting of US adults, were analyzed. SES indicators such as income and education were examined as predictors of internal and external health locus of control. The analyses were conducted overall without and with race interactions. We also ran models within different racial groups.

Results: Overall, 3198 participants entered our analysis who were White or Black. From this number, 2925 (91.5%) were White and 273(8.5%) were Black. In the pooled sample, high education and income were linked to higher internal and lower external health locus of control and lower BMI. The study revealed that the relationships between high SES indicators (income and education), internal health locus of control, and BMI were weaker for Black than White individuals. The study revealed that the relationships between high SES indicators (income and education) and external health locus of control was stronger for Black than White individuals.

Conclusion: This study provides evidence for the complex interrelationships between SES, health locus of control, and BMI, while highlighting the role of race as a moderating factor. The findings suggest that the effects of SES on internal health locus of control is influenced by race, with weaker relationships observed among Black individuals compared to Whites.

The Association Between Depression, Anxiety and COVID-19 Symptoms

Marilyn M. Bartholmae 1,2* , Joshua, M. Sill 3 , Matvey V. Karpov 1 , Sunita Dodani 1,4 1 EVMS-Sentara Healthcare Analytics and Delivery Science Institute, Norfolk, VA, USA 2 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA, USA 3 Division of Pulmonology, Department of Internal Medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA, USA 4 Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA, USA

Background: The variation of COVID-19 illness is not fully understood. There is a need for further identification of predictors for COVID-19-related health outcomes, which may improve the delivery of healthcare. The primary objective was to identify whether anxiety/depression symptoms are associated with the number of COVID-19 symptoms. The second objective was to examine differences in anxiety and depression symptoms between individuals with or without COVID-19 symptoms.

Methods: 782 Virginians ages 18 to 87 years, enrolled from March to May 2021 and were followed-up for six months. Vibrent Health online platform was used to collect data. PHQ-9, GAD-7, and CDC's COVID-19 tracing form, were used to assess depression, anxiety, and COVID-19 symptoms, respectively. An MMRM test was used to examine whether anxiety and depression symptoms were associated with the number of COVID-19 symptoms. Age, race, sex, medical diagnoses, and COVID-19 related economic/social hardships were included as covariates. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to assess differences in anxiety/depression at all study time points. We conducted analyses using SAS 9.4, p- values < .05 were considered significant.

Results: Depression/anxiety symptoms, COVID-19 related economic/social hardships, and medical diagnoses, were significantly associated with the number of COVID-19 symptoms ( p <.05), whereas age, sex, and race were not ( p >.05). Overall, PHQ9 and GAD7 scores were consistently and significantly higher for individuals with COVID-19 symptoms than those without COVID-19 symptoms ( p <.05).

Conclusions: The severity of depression and anxiety symptoms is linked to symptoms of COVID-19 over time. Physical and mental health integrated healthcare approaches may be necessary. Further investigation into causative mechanisms is needed.

Does Mental Health impact the outcomes of Total Ankle Arthroplasty? A Systematic Review

Margaret A. Sinkler 1* , Amir H. Karimi 2 , Mohamed E. El-Abtah 2 , John E. Feighan 1 , Ethan R. Harlow 1 , Heather A. Vallier 2 1 University Hospitals, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA 2 Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA

Studies have demonstrated that depression, anxiety, negative mood, and pain catastrophizing influence outcomes following total hip, knee, and shoulder arthroplasty thus providing evidence-based counseling on expected postoperative outcomes. The purpose of this review is to establish the prevalence of mental health conditions, impact of mental health conditions on patient-reported outcome measures, and the impact on length of stay and discharge disposition in patients undergoing total ankle arthroplasty (TAA). An online search utilizing the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed, Google Scholar, and CINAHL databases was performed to identify relevant articles published between 2010 and 2022. Seven studies were included in the systematic review. Depression was the most common mental health comorbidity with a pooled prevalence of 12.9%. Mental health comorbidities were associated with inferior patient reported outcomes measures. Additionally, depression was a pre-operative predictive factor in poor outcomes when utilizing the PROMIS score. The presence of a mental health comorbidity demonstrated an increased risk of nonhome discharge, length of stay, complication rate, infection, and narcotic use. Psychiatric comorbidities, particularly depression, were predictors of negative postoperative outcomes. This review reinforces the significant impact of mental health disorders and psychiatric comorbidities on clinical outcomes following TAA.

Level of Evidence: Level III

The Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of the Western Populace: A Model for the Examination of the Virus’s Global Impacts on Mental Health

Watson Kemper 1 , Katie Ben-Judah 2 , Akamu J. Ewunkem 3 , Uchenna B. Iloghalu 2* 1 Department of Biology, North Carolina A & T State University, Greensboro, NC, USA 2 Department of Biology, Guilford College, Greensboro, NC, USA 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Winston-Salem State University, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

COVID-19 has had lasting impacts on the physical and mental health of the global community. These impacts are multifaceted and spring from a range of physiological, psychological, economic origins. This review sought to demonstrate evidence of the damaging consequences that COVID-19 and its related effects have had on mental health. The findings showed significant increases in numbers of individuals seeking mental health care, experiencing negative mental health symptoms, and opting for medication management of mental health symptoms. In this review, we explore logistical aspects of both present and prospective zoonotic disease spillover events, as this information is key to mitigating future pandemic events. Furthermore, we summarize current knowledge of the impact of COVID-19 on mental health of the populations of Western countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy. Moreover, we discuss the influence of racial disparities in delivery of healthcare in the United States and their effects on the quality of, access to, and awareness of mental health care. Our awareness of these issues has the potential to inform further research, aid, and funding to the populations where it is most needed. Finally, we make recommendations for the direction of further research based on the findings of this article.

Racial disparities in opioid use disorder and its treatment: A review and commentary on the literature

Sean Lynch 1,2 , Faris Katkhuda 2,3 , Lidia Klepacz 2,4 , Eldene Towey 2,4 , Stephen J. Ferrando 2,4* 1 Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Mount Sinai Beth Israel, NY, USA 2 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, New York Medical College, School of Medicine, NY, USA 3 Department of Psychiatry, Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts, USA 4 Department of Psychiatry, Westchester Medical Center Health Network, Behavioral Health Center, NY, USA

Despite public interventions, the rate of opioid use disorder (OUD) continues to rise. In this focused review of the existing literature, the authors describe how increases in OUD, as well as opioid-related deaths, have occurred disproportionately among people of color. Black patients in particular are dying of overdose at an increased rate, however are less likely to receive any treatment for OUD. Additionally, Black patients are less likely to receive buprenorphine than White patients, but more likely to receive methadone. Potential causes of these disparities are discussed, as well as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the successes of several pilot programs.

Longitudinal trajectories of region-level suicide mortality in Tokyo, Japan, 2011 to 2021

Asuka Suzuki 1 , Kazue Yamaoka 1 *, Mariko Inoue 1 , Toshiro Tango 2,1 1 Teikyo University Graduate School of Public Health, Tokyo, Japan 2 Center for Medical Statistics, Tokyo, Japan

Background: Suicide mortality in Japan has declined over a period of more than 10 years, however, differences in longitudinal trajectories at a regional level are not well characterized. Objective was to clarify the longitudinal suicide mortality trajectories at the regional level in Tokyo from 2011 to 2021 by considering spatial smoothing, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods : This longitudinal cross-sectional analysis used fifty-four regions in Tokyo, Japan. Suicide mortality trends used data from the Cabinet Office of the Japanese government from 2011 to 2021. Regional social and environmental characteristics were used as 10 covariates. Empirical Bayes estimates for the standardized mortality ratio were obtained. A conditional autoregressive (CAR) model was applied to capture the spatial correlation for a crude and adjusted with 10 covariates using OpenBUGS. Spatial clusters were also identified by FlexScan, SaTScan, and Tango’s test.

Results: Longitudinal trajectories for both males and females were similar to a decreasing trend in all Japan until 2019. In 2020, the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the age-specific suicide deaths were the highest among those in their 20s. However, those were the highest among males in their 50s in 2021. The results of the CAR models adjusted for 10 covariates detected several regions as having higher suicide rates, but those regions were somewhat varied.

Conclusion: During the COVID-19 pandemic, both sexes in their 20s and males in their 50s showed a tendency toward an increase in suicides. The detected regions by spatial epidemiology varied with sex.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Mental Health Prevention and Promotion—A Narrative Review

Vijender singh, akash kumar, snehil gupta.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Samrat Singh Bhandari, Sikkim Manipal University, India

Reviewed by: Seshadri Sekhar Chatterjee, West Bengal University of Health Sciences, India; Arabinda Brahma, Girindra Sekhar Clinic Kolkata, India; Olusegun Baiyewu, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

*Correspondence: Snehil Gupta [email protected]

This article was submitted to Public Mental Health, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry

Received 2022 Mar 16; Accepted 2022 Jun 8; Collection date 2022.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Extant literature has established the effectiveness of various mental health promotion and prevention strategies, including novel interventions. However, comprehensive literature encompassing all these aspects and challenges and opportunities in implementing such interventions in different settings is still lacking. Therefore, in the current review, we aimed to synthesize existing literature on various mental health promotion and prevention interventions and their effectiveness. Additionally, we intend to highlight various novel approaches to mental health care and their implications across different resource settings and provide future directions. The review highlights the (1) concept of preventive psychiatry, including various mental health promotions and prevention approaches, (2) current level of evidence of various mental health preventive interventions, including the novel interventions, and (3) challenges and opportunities in implementing concepts of preventive psychiatry and related interventions across the settings. Although preventive psychiatry is a well-known concept, it is a poorly utilized public health strategy to address the population's mental health needs. It has wide-ranging implications for the wellbeing of society and individuals, including those suffering from chronic medical problems. The researchers and policymakers are increasingly realizing the potential of preventive psychiatry; however, its implementation is poor in low-resource settings. Utilizing novel interventions, such as mobile-and-internet-based interventions and blended and stepped-care models of care can address the vast mental health need of the population. Additionally, it provides mental health services in a less-stigmatizing and easily accessible, and flexible manner. Furthermore, employing decision support systems/algorithms for patient management and personalized care and utilizing the digital platform for the non-specialists' training in mental health care are valuable additions to the existing mental health support system. However, more research concerning this is required worldwide, especially in the low-and-middle-income countries.

Keywords: mental health, promotion, prevention, protection, intervention, review, preventive psychiatry, novel interventions

Introduction

Mental disorder has been recognized as a significant public health concern and one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, particularly with the loss of productive years of the sufferer's life ( 1 ). The Global Burden of Disease report (2019) highlights an increase, from around 80 million to over 125 million, in the worldwide number of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) attributable to mental disorders. With this surge, mental disorders have moved into the top 10 significant causes of DALYs worldwide over the last three decades ( 2 ). Furthermore, this data does not include substance use disorders (SUDs), which, if included, would increase the estimated burden manifolds. Moreover, if the caregiver-related burden is accounted for, this figure would be much higher. Individual, social, cultural, political, and economic issues are critical mental wellbeing determinants. An increasing burden of mental diseases can, in turn, contribute to deterioration in physical health and poorer social and economic growth of a country ( 3 ). Mental health expenditure is roughly 3–4% of their Gross Domestic Products (GDPs) in developed regions of the world; however, the figure is abysmally low in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) ( 4 ). Untreated mental health and behavioral problems in childhood and adolescents, in particular, have profound long-term social and economic adverse consequences, including increased contact with the criminal justice system, lower employment rate and lesser wages among those employed, and interpersonal difficulties ( 5 – 8 ).

Need for Mental Health (MH) Prevention

Longitudinal studies suggest that individuals with a lower level of positive wellbeing are more likely to acquire mental illness ( 9 ). Conversely, factors that promote positive wellbeing and resilience among individuals are critical in preventing mental illnesses and better outcomes among those with mental illness ( 10 , 11 ). For example, in patients with depressive disorders, higher premorbid resilience is associated with earlier responses ( 12 ). On the contrary, patients with bipolar affective- and recurrent depressive disorders who have a lower premorbid quality of life are at higher risk of relapses ( 13 ).

Recently there has been an increased emphasis on the need to promote wellbeing and positive mental health in preventing the development of mental disorders, for poor mental health has significant social and economic implications ( 14 – 16 ). Research also suggests that mental health promotion and preventative measures are cost-effective in preventing or reducing mental illness-related morbidity, both at the society and individual level ( 17 ).

Although the World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing and not merely an absence of disease or infirmity,” there has been little effort at the global level or stagnation in implementing effective mental health services ( 18 ). Moreover, when it comes to the research on mental health (vis-a-viz physical health), promotive and preventive mental health aspects have received less attention vis-a-viz physical health. Instead, greater emphasis has been given to the illness aspect, such as research on psychopathology, mental disorders, and treatment ( 19 , 20 ). Often, physicians and psychiatrists are unfamiliar with various concepts, approaches, and interventions directed toward mental health promotion and prevention ( 11 , 21 ).

Prevention and promotion of mental health are essential, notably in reducing the growing magnitude of mental illnesses. However, while health promotion and disease prevention are universally regarded concepts in public health, their strategic application for mental health promotion and prevention are often elusive. Furthermore, given the evidence of substantial links between psychological and physical health, the non-incorporation of preventive mental health services is deplorable and has serious ramifications. Therefore, policymakers and health practitioners must be sensitized about linkages between mental- and physical health to effectively implement various mental health promotive and preventive interventions, including in individuals with chronic physical illnesses ( 18 ).

The magnitude of the mental health problems can be gauged by the fact that about 10–20% of young individuals worldwide experience depression ( 22 ). As described above, poor mental health during childhood is associated with adverse health (e.g., substance use and abuse), social (e.g., delinquency), academic (e.g., school failure), and economic (high risk of poverty) adverse outcomes in adulthood ( 23 ). Childhood and adolescence are critical periods for setting the ground for physical growth and mental wellbeing ( 22 ). Therefore, interventions promoting positive psychology empower youth with the life skills and opportunities to reach their full potential and cope with life's challenges. Comprehensive mental health interventions involving families, schools, and communities have resulted in positive physical and psychological health outcomes. However, the data is limited to high-income countries (HICs) ( 24 – 28 ).

In contrast, in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) that bear the greatest brunt of mental health problems, including massive, coupled with a high treatment gap, such interventions remained neglected in public health ( 29 , 30 ). This issue warrants prompt attention, particularly when global development strategies such as Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) realize the importance of mental health ( 31 ). Furthermore, studies have consistently reported that people with socioeconomic disadvantages are at a higher risk of mental illness and associated adverse outcomes; partly, it is attributed to the inequitable distribution of mental health services ( 32 – 35 ).

Scope of Mental Health Promotion and Prevention in the Current Situation

Literature provides considerable evidence on the effectiveness of various preventive mental health interventions targeting risk and protective factors for various mental illnesses ( 18 , 36 – 42 ). There is also modest evidence of the effectiveness of programs focusing on early identification and intervention for severe mental diseases (e.g., schizophrenia and psychotic illness, and bipolar affective disorders) as well as common mental disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression, stress-related disorders) ( 43 – 46 ). These preventive measures have also been evaluated for their cost-effectiveness with promising findings. In addition, novel interventions such as digital-based interventions and novel therapies (e.g., adventure therapy, community pharmacy program, and Home-based Nurse family partnership program) to address the mental health problems have yielded positive results. Likewise, data is emerging from LMICs, showing at least moderate evidence of mental health promotion intervention effectiveness. However, most of the available literature and intervention is restricted mainly to the HICs ( 47 ). Therefore, their replicability in LMICs needs to be established and, also, there is a need to develop locally suited interventions.

Fortunately, there has been considerable progress in preventive psychiatry over recent decades, including research on it. In the light of these advances, there is an accelerated interest among researchers, clinicians, governments, and policymakers to harness the potentialities of the preventive strategies to improve the availability, accessibility, and utility of such services for the community.

The Concept of Preventive Psychiatry

Origins of preventive psychiatry.

The history of preventive psychiatry can be traced back to the early 1900's with the foundation of the national mental health association (erstwhile mental health association), the committee on mental hygiene in New York, and the mental health hygiene movement ( 48 ). The latter emphasized the need for physicians to develop empathy and recognize and treat mental illness early, leading to greater awareness about mental health prevention ( 49 ). Despite that, preventive psychiatry remained an alien concept for many, including mental health professionals, particularly when the etiology of most psychiatric disorders was either unknown or poorly understood. However, recent advances in our understanding of the phenomena underlying psychiatric disorders and availability of the neuroimaging and electrophysiological techniques concerning mental illness and its prognosis has again brought the preventive psychiatry in the forefront ( 1 ).

Levels of Prevention

The literal meaning of “prevention” is “the act of preventing something from happening” ( 50 ); the entity being prevented can range from the risk factors of the development of the illness, the onset of illness, or the recurrence of the illness or associated disability. The concept of prevention emerged primarily from infectious diseases; measures like mass vaccination and sanitation promotion have helped prevent the development of the diseases and subsequent fatalities. The original preventive model proposed by the Commission on Chronic Illness in 1957 included primary, secondary, and tertiary preventions ( 48 ).

The Concept of Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Prevention

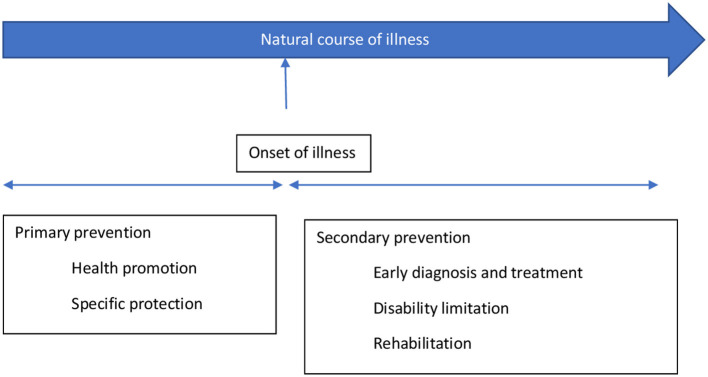

The stages of prevention target distinct aspects of the illness's natural course; the primary prevention acts at the stage of pre-pathogenesis, that is, when the disease is yet to occur, whereas the secondary and tertiary prevention target the phase after the onset of the disease ( 51 ). Primary prevention includes health promotion and specific protection, while secondary and tertairy preventions include early diagnosis and treatment and measures to decrease disability and rehabilitation, respectively ( 51 ) ( Figure 1 ).

The concept of primary and secondary prevention [adopted from prevention: Primary, Secondary, Tertiary by Bauman et al. ( 51 )].

The primary prevention targets those individuals vulnerable to developing mental disorders and their consequences because of their bio-psycho-social attributes. Therefore, it can be viewed as an intervention to prevent an illness, thereby preventing mental health morbidity and potential social and economic adversities. The preventive strategies under it usually target the general population or individuals at risk. Secondary and tertiary prevention targets those who have already developed the illness, aiming to reduce impairment and morbidity as soon as possible. However, these measures usually occur in a person who has already developed an illness, therefore facing related suffering, hence may not always be successful in curing or managing the illness. Thus, secondary and tertiary prevention measures target the already exposed or diagnosed individuals.

The Concept of Universal, Selective, and Indicated Prevention

The classification of health prevention based on primary/secondary/tertiary prevention is limited in being highly centered on the etiology of the illness; it does not consider the interaction between underlying etiology and risk factors of an illness. Gordon proposed another model of prevention that focuses on the degree of risk an individual is at, and accordingly, the intensity of intervention is determined. He has classified it into universal, selective, and indicated prevention. A universal preventive strategy targets the whole population irrespective of individual risk (e.g., maintaining healthy, psychoactive substance-free lifestyles); selective prevention is targeted to those at a higher risk than the general population (socio-economically disadvantaged population, e.g., migrants, a victim of a disaster, destitute, etc.). The indicated prevention aims at those who have established risk factors and are at a high risk of getting the disease (e.g., family history of psychiatric illness, history of substance use, certain personality types, etc.). Nevertheless, on the other hand, these two classifications (the primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention; and universal, selective, and indicated prevention) have been intended for and are more appropriate for physical illnesses with a clear etiology or risk factors ( 48 ).

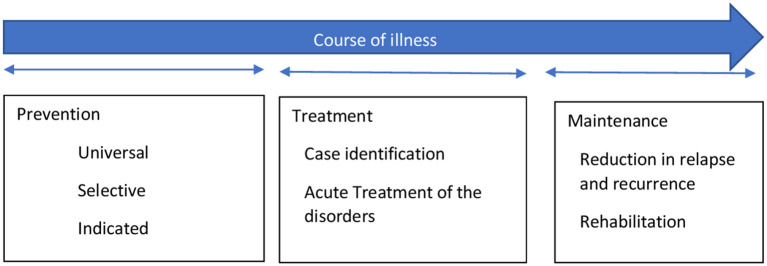

In 1994, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders proposed a new paradigm that classified primary preventive measures for mental illnesses into three categories. These are indicated, selected, and universal preventive interventions (refer Figure 2 ). According to this paradigm, primary prevention was limited to interventions done before the onset of the mental illness ( 48 ). In contrast, secondary and tertiary prevention encompasses treatment and maintenance measures ( Figure 2 ).

The interventions for mental illness as classified by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders [adopted from Mrazek and Haggerty ( 48 )].

Although the boundaries between prevention and treatment are often more overlapping than being exclusive, the new paradigm can be used to avoid confusion stemming from the common belief that prevention can take place at all parts of mental health management ( 48 ). The onset of mental illnesses can be prevented by risk reduction interventions, which can involve reducing risk factors in an individual and strengthening protective elements in them. It aims to target modifiable factors, both risk, and protective factors, associated with the development of the illness through various general and specific interventions. These interventions can work across the lifespan. The benefits are not restricted to reduction or delay in the onset of illness but also in terms of severity or duration of illness ( 48 ).On the spectrum of mental health interventions, universal preventive interventions are directed at the whole population without identifiable risk factors. The interventions are beneficial for the general population or sub-groups. Prenatal care and childhood vaccination are examples of preventative measures that have benefited both physical and mental health. Selective preventive mental health interventions are directed at people or a subgroup with a significantly higher risk of developing mental disorders than the general population. Risk groups are those who, because of their vulnerabilities, are at higher risk of developing mental illnesses, e.g., infants with low-birth-weight (LBW), vulnerable children with learning difficulties or victims of maltreatment, elderlies, etc. Specific interventions are home visits and new-born day care facilities for LBW infants, preschool programs for all children living in resource-deprived areas, support groups for vulnerable elderlies, etc. Indicated preventive interventions focus on high-risk individuals who have developed minor but observable signs or symptoms of mental disorder or genetic risk factors for mental illness. However, they have not fulfilled the criteria of a diagnosable mental disorder. For instance, the parent-child interaction training program is an indicated prevention strategy that offers support to children whose parents have recognized them as having behavioral difficulties.

The overall objective of mental health promotion and prevention is to reduce the incidence of new cases, additionally delaying the emergence of mental illness. However, promotion and prevention in mental health complement each other rather than being mutually exclusive. Moreover, combining these two within the overall public health framework reduces stigma, increases cost-effectiveness, and provides multiple positive outcomes ( 18 ).

How Prevention in Psychiatry Differs From Other Medical Disorders

Compared to physical illnesses, diagnosing a mental illness is more challenging, particularly when there is still a lack of objective assessment methods, including diagnostic tools and biomarkers. Therefore, the diagnosis of mental disorders is heavily influenced by the assessors' theoretical perspectives and subjectivity. Moreover, mental illnesses can still be considered despite an individual not fulfilling the proper diagnostic criteria led down in classificatory systems, but there is detectable dysfunction. Furthermore, the precise timing of disorder initiation or transition from subclinical to clinical condition is often uncertain and inconclusive ( 48 ). Therefore, prevention strategies are well-delineated and clear in the case of physical disorders while it's still less prevalent in mental health parlance.

Terms, Definitions, and Concepts

The terms mental health, health promotion, and prevention have been differently defined and interpreted. It is further complicated by overlapping boundaries of the concept of promotion and prevention. Some commonly used terms in mental health prevention have been tabulated ( Table 1 ) ( 18 ).

Commonly used terms in mental health prevention.

Mental Health Promotion and Protection

The term “mental health promotion” also has definitional challenges as it signifies different things to different individuals. For some, it means the treatment of mental illness; for others, it means preventing the occurrence of mental illness; while for others, it means increasing the ability to manage frustration, stress, and difficulties by strengthening one's resilience and coping abilities ( 54 ). It involves promoting the value of mental health and improving the coping capacities of individuals rather than amelioration of symptoms and deficits.

Mental health promotion is a broad concept that encompasses the entire population, and it advocates for a strengths-based approach and tries to address the broader determinants of mental health. The objective is to eliminate health inequalities via empowerment, collaboration, and participation. There is mounting evidence that mental health promotion interventions improve mental health, lower the risk of developing mental disorders ( 48 , 55 , 56 ) and have socioeconomic benefits ( 24 ). In addition, it strives to increase an individual's capacity for psychosocial wellbeing and adversity adaptation ( 11 ).

However, the concepts of mental health promotion, protection, and prevention are intrinsically linked and intertwined. Furthermore, most mental diseases result from complex interaction risk and protective factors instead of a definite etiology. Facilitating the development and timely attainment of developmental milestones across an individual's lifespan is critical for positive mental health ( 57 ). Although mental health promotion and prevention are essential aspects of public health with wide-ranging benefits, their feasibility and implementation are marred by financial and resource constraints. The lack of cost-effectiveness studies, particularly from the LMICs, further restricts its full realization ( 47 , 58 , 59 ).

Despite the significance of the topic and a considerable amount of literature on it, a comprehensive review is still lacking that would cover the concept of mental health promotion and prevention and simultaneously discusses various interventions, including the novel techniques delivered across the lifespan, in different settings, and level of prevention. Therefore, this review aims to analyze the existing literature on various mental health promotion and prevention-based interventions and their effectiveness. Furthermore, its attempts to highlight the implications of such intervention in low-resource settings and provides future directions. Such literature would add to the existing literature on mental health promotion and prevention research and provide key insights into the effectiveness of such interventions and their feasibility and replicability in various settings.

Methodology

For the current review, key terms like “mental health promotion,” OR “protection,” OR “prevention,” OR “mitigation” were used to search relevant literature on Google Scholar, PubMed, and Cochrane library databases, considering a time period between 2000 to 2019 ( Supplementary Material 1 ). However, we have restricted our search till 2019 for non-original articles (reviews, commentaries, viewpoints, etc.), assuming that it would also cover most of the original articles published until then. Additionally, we included original papers from the last 5 years (2016–2021) so that they do not get missed out if not covered under any published review. The time restriction of 2019 for non-original articles was applied to exclude papers published during the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic as the latter was a significant event, bringing about substantial change and hence, it warranted a different approach to cater to the MH needs of the population, including MH prevention measures. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the flooding of novel interventions for mental health prevention and promotion, specifically targeting the pandemic and its consequences, which, if included, could have biased the findings of the current review on various MH promotion and prevention interventions.

A time frame of about 20 years was taken to see the effectiveness of various MH promotion and protection interventions as it would take substantial time to be appreciated in real-world situations. Therefore, the current paper has put greater reliance on the review articles published during the last two decades, assuming that it would cover most of the original articles published until then.

The above search yielded 320 records: 225 articles from Google scholar, 59 articles from PubMed, and 36 articles from the Cochrane database flow-diagram of records screening. All the records were title/abstract screened by all the authors to establish the suitability of those records for the current review; a bibliographic- and gray literature search was also performed. In case of any doubts or differences in opinion, it was resolved by mutual discussion. Only those articles directly related to mental health promotion, primary prevention, and related interventions were included in the current review. In contrast, records that discussed any specific conditions/disorders (post-traumatic stress disorders, suicide, depression, etc.), specific intervention (e.g., specific suicide prevention intervention) that too for a particular population (e.g., disaster victims) lack generalizability in terms of mental health promotion or prevention, those not available in the English language, and whose full text was unavailable were excluded. The findings of the review were described narratively.

Interventions for Mental Health Promotion and Prevention and Their Evidence

Various interventions have been designed for mental health promotion and prevention. They are delivered and evaluated across the regions (high-income countries to low-resource settings, including disaster-affiliated regions of the world), settings (community-based, school-based, family-based, or individualized); utilized different psychological constructs and therapies (cognitive behavioral therapy, behavioral interventions, coping skills training, interpersonal therapies, general health education, etc.); and delivered by different professionals/facilitators (school-teachers, mental health professionals or paraprofessionals, peers, etc.). The details of the studies, interventions used, and outcomes have been provided in Supplementary Table 1 . Below we provide the synthesized findings of the available research.