Ecological Perspective Theory and Practice Essay

Introduction, theoretical concepts, strengths and weaknesses, theoretical implications, illustrations of theory in social work, ecological perspective in issues of inequality and discrimination.

Ecology as a study of the interrelation of beings and their environment has taken a broader concept, influencing other disciplines from a wide variety of fields. The ecological perspective can be seen as an approach in which the focus is on the interactions and the transactions between people and their environment (Greene, 2008). This can be seen through the main elements of focus in the ecological perspective; one of the main concepts in studying the ecological traditions lies in social theories and development psychology. The core of the ecological perspective is ecology, which serves as the basis for the interpretation as well as source for the major terms employed in the concept (Bronfenbrenner,1979).

With more and more practical implementation of the ecological perspective in a variety of disciplines, there is an interest in studying the theoretical foundations of this perspective.

This essay will provide a comprehensive overview of the theoretical concepts in the ecological perspective, its strengths and weakness, and several examples on the way this perspective is integrated into practical aspects.

The ecological perspective refers to several ecological models that study a numeral factors within the environment that shape people’s behaviour. The factors of the environment might be related to both, physical and socio-cultural surroundings, which include environmental and policy variables within a wide range of influences at many levels (Sallis et al, 2006). The purpose of such models is to seek and identify the causes of a particular behaviour in the environment, according to which an intervention might be designed (McLeroy et al., 1988).

One of the ecological models as proposed by Bronfenbrenner defines the ecological perspective as the scientific study of the progressive, mutual accommodation, throughout the life course between an active , growing human being and his or her environment. This model derives its main terms from the field of ecology, in which the ecological environment is the arrangement of structures, each contained within the next (Bronfenbrenner, 1977), while the levels of influence in such environment are employed in Microsystems meco-system, macro- system and exo-systems. The microsystem levels can be described as the personal interactions within a specific setting.

The setting can be seen as the place in which the person can engage in different activities and play different roles, e.g. home, school, hospital, etc. The physical features of the place, the roles played, the time, and the activity, all represent elements of the setting. A mesosystem, on the other hand, represents the interrelations between major settings, for example, for a student, mesosystem might be represented through the interrelations between home and a school or college.

The exosystem contains the structures, in which a person does not participate, but influences the immediate setting in which the person is located. In that regard, the exosystem can be seen as the forces in social systems, such as governmental institutions and structures, example, the distribution of goods, communications, transportations, and other social networks (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). A macrosystem is mainly concerned with the patterns of the culture and subculture, examined in structural terms as well as carriers of information and ideology. The work of Bronfenbrenner can be considered as the traditional representation of the ecological perspective, upon which this perspective was further expanded and modified.

The aforementioned model was slightly modified to categorise the level of influence into two broad categories, intra- individual (person) and extra – individual (environment). The intra influences included individual attributes, beliefs, values, attitudes and behaviours, while the extra influences included such aspects “environmental topography, social and cultural contexts and policies (Spence and Lee, 2003). It can be stated that the changes that result from a particular influence are mostly categorised into two approaches, which are adaptation and coping. Adaptation can be defined as the capacity to conduct adjustments to the changes in the environmental conditions (Zastrow and Kirst-Ashman, 2007).

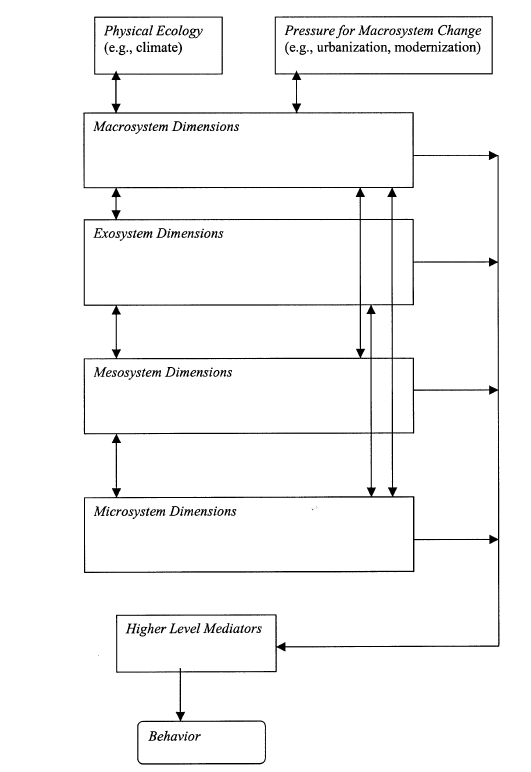

The latter is utilized in improving the individual-environment fit, which can be achieved through changes at intra-individual or extra individual levels (Spence and Lee, 2003). Coping on the other hand, refers to a form of adaptation that implies struggle, and it’s generally used to refer to the response to negative conditions. The structural model of the environment adapted from Bronfenbrenner was categorised in a hierarchical multilevel and multidimensional fashion, which describes a dynamic system that operates in space and time. The way the system was adapted can be seen in Fig 1.

It should be noted that the theoretical models of the ecological perspective reviewed in Spence and Lee(2003) outlined other classifications of the environmental influences, among which are the availability and the constraints of resources, the physical structure, the social structure, and cultural and media message. The influence of resource is a significant factor, as it will be outlined in the implications sectors, where to understand a phenomenon the assessment of the factor of resources is essential. The resources were also outlined in Berkman and Glass (2000) in which model the social networks were connected to health.

The model was adapted to the health context and thus, the micro level influence included factors that were affecting health behaviours such as the forces of social influence, levels of social engagement and participation, controlling the contact with infectious diseases, and access to material goods and resources (Berkman and Glass, 2000).

Another adaptation to the ecological model was that in which the levels of influence were expanded into a broader context to include intrapersonal factors, interpersonal processes, institutional factors, community factors, and public policy (McLeroy et al., 1988). Such model was modified specifically for analysing health promotion, where the outcome of the influence of aforementioned factors is patterned behaviour, that is the subject of the analysis in this conceptual model.

The rationale for the provided adjustment can be seen as different levels of factors will facilitate assessing the unique characteristics of different levels of interventions. It should be noted that interventions is an essential aspect in the assessment of the theoretical foundations of ecological perspective, where the theory serves as a method of conceptualising a particular model.

Within the field of environmental psychology, the ecological perspective was one of the areas of emphasis through the span of the field’s development. With a variety of ecological models, which were adapted into different fields, for example, health promotion, physical activities, developmental psychology, these models share many common characteristics, which form the ecological perspective in general. These characteristics include the focus on the dynamic interaction between the individual and his/her environment, the focus on the person and the environment as a single entity, combining concepts from many disciplines, and taking a context-specific view of behaviour (Greene, 2008).

It is noted that the ecological perspective shares common concepts from the systems theory, which is “the transdisciplinary study of the abstract organisation of phenomena, independent of their substance, type, or spatial or temporal scale of existence” (Heylighen and Joslyn, 1992). The common characteristics can be seen when assuming the complex phenomena are the people and their activities. Additionally, common notions exist between the two theories, for example, interface, which is the point of interaction between the individual and the environment, where the difference might be seen in that the emphasis in ecological perspective is on interfaces concerning individuals and small groups (Zastrow and Kirst-Ashman, 2007).

Sharing concepts with systems theories, the ecological perspective also contribute to the ecosystem perspective, a perspective which was derived from the systems theories and ecology. Being mainly applied in social work, the ecosystems perspective focus on the complexity of transactions occurring within a system, guiding the balance between the individual and the environment (Mattaini, 2008).

The strengths and the weakness of the ecological perspective can be divided between those general to the perspective and those specific for a particular ecological model.

The strengths can be outlined through the benefits of the different features of the ecological perspective. One of such features is taking account of the contexts of the environment. The reliance on such attribute as well as the variety of contexts that might be integrated in a specific model makes it easier to allows apply the ecological perspective to a variety of disciplines and fields.

The areas of social work practice, in which the knowledge about the context can be valued, include prisons, hospitals, and schools. In the example of school, the value of the ecological approach is suggested through relating the knowledge about the context to the key occupation group in such setting, e.g. teachers or other professionals (Davies, 2002). Similarly, working with children and their families, the importance of the understanding the context can be seen one of the ecological approach’s strengths that advocates the use of such approach in social work.

The context in such case is within the child’s family, the community and the culture, understanding which facilitates obtaining an insight into the child’s development (Beckett, 2006). Additionally, such strength allowed the inclusion of the ecological approach in the national Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families, in which the assessment of the children’s needs is conducted taking account of three domains, developmental needs, parents’ or caregivers capacities, and wider environmental factors (Department of Health, 2000).

Nevertheless, it should be stated that the utilisation of contexts might present challenges to researches. Such challenges are mainly statistical and are mentioned about the area of ecological psychology, although it might be assumed that the same can be witnessed in other areas as well. A representation of such statistical challenges can be seen in the usage of physical variables to address individual outcomes, rather than general outcomes (Winkel et al., 2009).

Another strong argument in favour of the ecological perspective can be seen in its broad approach toward studying the relationship between the environment and the individual. The fact that many of the levels of influence include those to which the individual is not directly attached, but still influenced by them, is one of the strengths of the ecological perspectives. Additionally, it can be stated that the limitations of the prevailing scientific approaches to study human development contributed to considering the ecological perspective, proposed by Bronfenbrenner.

The broadness strength can be rephrased as the ability to examine multiperson systems without limitation to a single setting, and taking into account both the immediate setting and the environment beyond (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). The broadness strength can be rephrased as the ability to examine of multiperson systems without limitation to a single setting, and taking into account both the immediate setting and the environment beyond

The weakness of the ecological perspective can be seen in the models adapted for social behaviour, although as stated earlier they might apply to other models as well. The weakness is mainly represented through the lack of specificity for conceptualisation of a particular problem.

The lack of such specificity combined with broadness approach highly subjected to interpretation. For example, the approach mentioned earlier in terms of generally assessing children in need, can be seen the same in terms of asylum seeking and refugee children specifically (National Children’s Bureau, 2006). Thus, it might be stated that the broadness of the approach makes it applicable to various contexts, and at the same time, the conceptualization of such applicability can be a difficult task.

In other cases, implementing the ecological approach while working with the population should make account of the ecological fallacy, which can be defined as relating the knowledge about a groups’ past behaviour to generalise them as real events(example, children brought up in deprived areas always end up as poor adults) (Adams et al,2009). Such weakness can be evident when working with such groups as confined individuals.

Thus, actual risk assessment has little success in some social work cases(Davies, 2002). For example, an experienced child protection service user may develop a strong capacity to predict situations of high risk drawing in part of what is observed in the environment which the child is found as well as the formal assessment risk framework but the outcome of this may have an adverse effect as that situation is most likely to be different from previously assessed ones(Healy,2005)

The same can be said about the identification of the interventions for specified problems (McLeroy et al., 1988). Such weakness is mainly mediated through the various adaptations of ecological models, which take the main framework and modify it to suit specific purposes. Additionally, other weaknesses can be viewed in terms of model applied for specific purposes, rather than general disadvantages.

For example, in health promotion, the limitation of the McLeroy model was said to be vague in terms of distinguishing the levels of intervention and settings (Richard et al, 1996). Additional weaknesses, which might be generalised toward all models under the ecological perspective, are concerned with the implementation in practice. Also, social work like any other discipline may find designing and implementing ecological programmes a challenge due to the complexity of the approach and the costs involved in operating it (Richard et al, 2004).

The basis for the theoretical implications of the ecological perspective can be seen through guiding and design intervention programmes, through addressing the way an interaction occurs at various levels of the specific theoretical model. Hence, following such principles within different areas and disciplines, the framework serves as an indication for which factors should be enabled, enforced and facilitated.

Taking for example the field of education, the ecological perspective might be used to provide a model for the integration of the technology in school. Such example was investigated in Zhao and Frank (2003), where the authors utilized an ecological metaphor of introducing a zebra mussel into the Great Lakes to identify the factors influencing the implementation of computer uses. Following the common elements of the reviewed framework, it can be stated that the school represent a setting within Bronfenbrenner systems, while Great Lakes is the setting within the chosen ecological metaphor.

The difference in the approach proposed in Zhao and Frank is in using an ecosystem, rather than setting, and thus, the context was narrowed to the schools, rather than societies. Paralleling computer uses within species and innovative technologies with exotic species, the authors constructed a framework for the interaction between the elements of the ecosystem. Such framework allowed narrowing down the levels of the influences, with the ultimate goal of determining the technology uses in classroom.

The test of the framework revealed that the dynamics of the school as an ecosystem affect the interactions between the new and existing species, that is computer uses and innovative technologies. Having a hypothetical ecology core, the framework based on the ecological perspective had practical implications among which is the focus on teachers as facilitators of change, the provision of training opportunities (Zhao and Frank, 2003).

With the following being related to the field of education as well as to the technology field, it can be stated that the implications of the ecological perspective are not necessarily applied through ecology metaphors and parallels to the nature. The field of sociology can be seen as of the most prominent examples of the application of ecological perspective. The purposes of applying the ecological perspective in social context might vary from identifying factors and determining cause to understanding the dynamics within a specific setting. As an example of the latter, the ecological perspective was applied in Jiang and Begun (2002) to understand the factors influencing the changes in the local physician supply in a particular area. The modelling process can be seen through the following steps:

- Applying the dynamics of growth in a population to the population of a particular specialty type of physicians, and formulating a model.

- Identifying the intrinsic properties of the selected population. In this case the dimensions identified for such purpose include the width of the physicians’ niche and capital intensity.

- Describe the environment. In this case the dimensions for description are munificence, concentration, and diversity.

- Outline the resources in the environment, e.g. the size of the patient population, the hospital supply, and the economic wealth of the environment.

- Applying the factors and the descriptions to the identified model.

- Testing the model.

The abovementioned utilization of the ecological perspective was proven applicable, and accordingly, several practical mechanisms were derived from such study. These mechanisms might be useful to identify the determinants of changes in one of the dimensions of the population or the indicated resources, such as the size, the specialty. Similarly, such model can be implemented in social work practices, as it will be illustrated in the following sections. The practitioner investigates each of the properties/characteristics of the systems participating in interaction processes. Accordingly, the individual or the population will be investigated as well as pressure factors causing the problem. Finally, an intervention is planned to deal with the factors contributing to the causality of the problem.

Another practical example of the application of the ecological perspective can be seen through investigating the changes that influence a particular part of the population. An example of the latter can be seen in a study by McHale, Dotterer, and Kim (2009), in which the methodological issues for researching the media and the development of youth were investigated in the context of the ecological perspective. The emphasis in such approach can be seen through the focus on activities, being a reflection of development, as outlined by Larson and Verma (1999), cited in McHale, Dotterer, and Kim (2009).

Another ecological influence on studying the development of youth can be seen in the multilayered contexts, “within which individuals are embedded” (McHale et al., 2009). It can be stated that the multilayered contexts are a representation of the levels of influences, whereas the youth, as a population are the subject of these influences. Thus, the environment in such perspective is not perceived as a separate entity, but rather as a collection of those levels of influences, that is contexts within the scope of the aforementioned model. The ecological model chosen for the depiction of such influences was the traditional Bronfenbrenner’ model, while the factors of influence were obtained through a review of the literature, as stated earlier.

The core of the model, which is the individual or the child in this context, is represented through a set of characteristics, such as the activity level, sociability, interests, activities, and others. Additionally, the most proximate level of influences to the child is the microsystem level, comprising of such factors as family, peer group, community neighbourhood, and schools (McHale et al., 2009). The applicability of this model can be see through outlining the context of the youth development, where the established framework narrows the areas of research to specific directions, which might imply particular methodological considerations. One of such considerations can be seen through the identification of variables, specifically in quantitative researches that investigate causal relationships.

The same can be seen about extraneous variables, which the framework might indicate. Other suggestions for the utilization of the ecological perspective in youth development researches might include highlighting the influence of specific factors, e.g. family income, or education, on youth activities, and assessing the role of the individuals themselves in their activities.

With the ecological perspective having a social context, such contexts often intersect with health approach. Among the attempts of integrating the ecological perspective into health improvement is a proposed model which is aimed at identifying the factors that will contribute to the success of tobacco control programmes (Richard et al,2004). Similarly, the factors integrated into the perspective were derived from literature, namely Scheirer’s framework which was successfully used in fields such as mental health.

The factors of the levels of influence were assigned to identify the factors of success, which were then tested as variables in a case study. The ecological perspective proved to be successful for its designated purpose, despite some limitations, and helped to identify configurations of environmental, organizational and professional characteristics that will facilitate the implementation of the programme (Richard et al, 2004).

Generally, it can be stated that the application of the ecological perspective in social work is mainly concerned with assessment and communication. Taking the example of practitioners working with families, the assessment might imply identifying factors related to the families culture, subculture and race.

One of the methods of working with family can be seen through group therapy and family therapy. Family therapy, which is grounded in the ecological perspective, is specifically emphasized, as most clients have family systems to work with. The assessment might be performed through the way through analyzing communication occurring between the family members participating in the therapy. For example, the practitioner might consider the way messages are sent and received within the family unit as well as the paths of communication. Such elements of the communication will provide an insight into the social environment in which the family functions, which can be seen as a part of the treatment.

Another model used to identify family problems is Minuchin’s model (Pardeck, 1996). Utilizing such model, practitioners will attempt to identify the factors of pressure, external for the family unit as well as coming from within. Such factors can be seen through either a pressure on a single member of the family, pressure on the entire family, pressure occurring when moving through life cycles, and idiosyncratic factors unique to the family.

The identification of the type of pressure can be implemented through the communication approach previously mentioned. The intervention can be seen in making corrections to the source of pressure, restoring the balance between the family unit and the environment. The correction can be seen through elimination the source of pressure, if possible, helping the family develop coping mechanism to deal with the pressure, inspecting the larger system in which the family functions, suggesting policies that might have a positive impact on the family’s interaction, and other. The weakness of such approach can be seen in the ecological fallacy, mentioned earlier.

On the one hand, practitioners might generalize the intervention or previous knowledge, assuming that all families experience the same pressure. At the same time, such generalization might not be applicable in present context.

Child protection is concerned with protection children from maltreatment, which according to the ecological perspective is the result of interaction between several factors and systems. Thus, the role of the practitioner can be seen in identifying the interactions that occur and the causality of maltreatment. The practitioner will gather information from the settings, in which the child interacts, including family assessment, in which the family background, history, and structure will be analyzed, the cultural differences, environmental factors in the community, such as poverty, violence, etc, and the services available to the family and the child.

Identifying the external factor, individual factors of the child should be assessed as well, in terms of growth, development, identity development, and others. Such information will be used by the practitioner to identify risks and protective factors, based on which an intervention will be planned to change the conditions and the behaviors that cause risks of maltreatment to occur. With the goal of the intervention set, the plan of the intervention will be implemented.

With discrimination and inequality being social phenomena, the ecological perspective can be used to explain them. Inequality, in that regard, occurs when a differentiation exists in hierarchical structures. Differentiation is perceived in ecological theories in static and dynamic perspectives, where in terms of statics, differentiation is the difference between groups concerning a particular variable, while in terms of dynamics, differentiation refers to processes that produce and maintain differences within and between groups. The ecological perspective helps in explaining inequality, viewing it as complex and multidimensional phenomenon (Maclean and Harrison,2006).

These factors include such distinct clusters: cultural differences, religious differences, compositional differences, and differential treatment (Micklin and Poston, 1998). In terms of discrimination, it can be viewed as a behaviour, which is recognized as a function of the person-environment interaction. Thus, the ecological perspective not only helps in understanding such behaviour and the influential factors, but also the interventions that might be designed in social justice advocacy (Greenleaf and Williams, 2009). Although the latter is mainly connected to the field of psychological counselling, it might be used in social work as well.

Nevertheless, the utilisation of the ecological perspective in explaining such aspects as inequality does not imply individualistic approaches, that is to say the ecological perspective does not operate on the micro-level, as ecologists view questions of such scale as unimportant. It should be stated that being perceived as unimportant does not necessarily mean that the ecological perspective is not applicable in such cases, where several studies found the ecological perspective to be relevant(Micklin and Poston, 1998). Social workers are aware of the importance of context in service users lives and ,understanding and responding to the individual in their environment is an essential part of social work practice(Healy,2005)

It can be concluded that the ecological perspective is a useful approach to analyse and explain various phenomena. The principle of examining the interrelations between the individual and the environment allows designing a framework that can be utilised in various fields and disciplines. The ecological perspective has a great potential, which can be used not only as an explanation and investigation of a phenomenon, but also as a useful mean for designing interventions for problems relating to social work as well as other disciplines(Payne,2005).

Adams, R., Dominelli, L. and Payne, M. (eds.), (2009) Themes, Issues and Critical Debates . Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Beckett, C., (2006) Essential theory for social work practice, London: SAGE.

Berkman, L. F. & Glass, T. (2000), Social integration, social networks, social support and health . In: Berkman, L. F. & Kawachi, I. (eds.) Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bronefenbrenner, U. (1977), Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development . American Psychologist, 32 , 513-531.

Davies, M., (2002) The Blackwell companion to social work, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers

Department Of Health, (2000) Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families. Web.

Grenne, R. R. (2008), Human behavior theory & social work practice, New Brunswick, N.J., Aldine Transaction.

Greenleaf, A. T. & Williams, J. M. (2009), Supporting Social Justice Advocacy: A Paradigm Shift towards an Ecological Perspective Journal for Social Action in Counselling and Psychology [Online], 2. Web.

Healy, K. (2005) Social Work Theories in Context: Creating frameworks for Practice. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan Heylighen, F. & Joslyn, C. (1992), What is Systems Theory? [Online]. Principia Cybernetica Web.

Jiang, H. J. & Begun, J. W. (2002) Dynamics of change in local physician supply: an ecological perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 54 , 1525-1541.

Maclean, S. And Harrison, R. (2008) SOCIAL WORK THEORY;A Straight forward Guide for Practice Assessors and Placement Supervisors .Staffordshire:Kirwin Maclean.

Mattaini, M. A. (2008) Ecosystems Theory. In: SOWERS, K. M. & DULMUS, C. N. (eds.) Comprehensive handbook of social work and social welfare. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons.

Mchale, S. M., Dotterer, A. & Kim, J.Y. (2009), An Ecological Perspective on the Media and Youth Development. American Behavioural Scientist, 52 , 1186-1203.

Mcleroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A. & Glanz, K. (1988), An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Educ Behav, 15 , 351-377.

Micklin, M. & Poston, D. L. (1998), Continuities in sociological human ecology, New York, Plenum Press.

National Children’s Bureau, (2006) The Ecological Approach to the Assessment of Asylum Seeking and Refugee Children. Web.

Pardeck, J. T., (1996) Social work practice : an ecological approach, Westport: Auburn House.

Payne, M. (2005), Modern Social Work Theory (3 rd Ed), New York: Palgrave MACMILLAN.

Richard, L., Lehoux, P., Breton, E., DENIS, J,L., Labrie, L. & Leonard, C. (2004), Implementing the ecological approach in tobacco control programs: results of a case study. Evaluation and Program Planning, 27 , 409-421.

Richard, L. P., Kishchuk, L., Prlic, N. & H. Green, L. W. (1996), Assessment of the Integration of the Ecological Approach in Health Promotion Programs. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF HEALTH PROMOTION, 10 , 318-328.

Sallis, J. F., Cervero, R. B., Ascher, W., Henderson, K. A., Kraft, M. K. & KERR, J. (2006), An Ecological Approach to Creating Active Living Communities. Annual Review of Public Health, 27 , 297–322.

Spence, J. C. & Lee, R. E.( 2003), Toward a comprehensive model of physical activity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 4 , 7-24.

Winkel, G., Saegert, S. & Evans, G. W. (2009), An ecological perspective on theory, methods, and analysis in environmental psychology: Advances and challenges. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29 , 318-328.

Zastrow, C. & KirstI-Ashman, K. K.( 2007), Understanding human behavior and the social environment, Belmont, CA, Thomson Higher Education.

Zhao, Y. & Frank, K. A. (2003), Factors Affecting Technology Uses in Schools: An Ecological Perspective. American Educational Research Journal, 40 , 807-840.

- EMS: Environmental Management Systems in Small and Medium Enterprises

- Water: The Element of Life

- Ecological Footprint Analysis

- The red sludge ecological disaster

- Global Warming From a Social Ecological Perspective

- Environmental Management: Toyota, Honda, Jaguar UK

- Waterborne Infections: Policy issues and Individual Input

- Shaq Petroleum Station Environmental Management

- Environmental Conservation: Anthropo- and Ecocentric Perspectives

- Modern Water Purification Methods for the Middle East

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 23). Ecological Perspective Theory and Practice. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ecological-perspective-theory-and-practice/

"Ecological Perspective Theory and Practice." IvyPanda , 23 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/ecological-perspective-theory-and-practice/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Ecological Perspective Theory and Practice'. 23 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Ecological Perspective Theory and Practice." December 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ecological-perspective-theory-and-practice/.

1. IvyPanda . "Ecological Perspective Theory and Practice." December 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ecological-perspective-theory-and-practice/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Ecological Perspective Theory and Practice." December 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ecological-perspective-theory-and-practice/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Ecological Perspective: Definition and Examples

Viktoriya Sus (MA)

Viktoriya Sus is an academic writer specializing mainly in economics and business from Ukraine. She holds a Master’s degree in International Business from Lviv National University and has more than 6 years of experience writing for different clients. Viktoriya is passionate about researching the latest trends in economics and business. However, she also loves to explore different topics such as psychology, philosophy, and more.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

The ecological perspective is a theoretical and practical approach to the social sciences that emphasizes the interactions between an individual and their environment.

This perspective views individuals as active agents who engage in reciprocal relationships with their physical, social, and cultural contexts.

The ecological perspective indicates that psychological factors can not be seen in isolation but must be understood concerning other factors at play within an individual’s surroundings.

For instance, a child’s development can be influenced by their immediate family or caretakers in the microsystem.

Still, it can also be affected by other macro factors like a parent’s job insecurity within the exosystem, which may affect their parenting style or ability to provide adequate resources for the child.

So, an ecological perspective acknowledges the complexity and interconnectedness of various aspects that shape human behavior and development.

Definition of Ecological Perspective

According to Lobo et al. (2018), the ecological perspective in psychology considers how multiple environmental factors influence human behavior and development.

This perspective emphasizes that individuals develop within and are influenced by complex systems of social, cultural, and physical environments.e

According to Satchell and colleagues (2021),

“…an ecological approach is about the understanding of individual’s perceived behavioral opportunities and gives important focus on what the environment might offer an individual in a place” (p. 1).

Fact File: Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

One of the most influential ecological perspectives is that of Urie Bronfenbrenner, who viewed individuals as situated within systems – microsystem, macrosystem, and ecosystem, each with different levels of influence (Crawford, 2020). For example, an individual’s immediate physical environment (microsystem) can include things like their home and school surroundings. The exosystem may include institutions like political entities or religious organizations in which people participate indirectly. And macro systems operate at cultural levels and encompass customs, norms, laws, and values.

The ecological perspective emphasizes studying individuals in a naturalistic setting using rigorous naturalistic observation methods to gain deep insight into an individual’s behavior vis-à-vis the environment (Heft, 2013).

For example, a study on the impact of poverty on child development might look at factors such as access to nutritious food or quality healthcare within a family’s immediate environment (microsystem).

Still, it also assesses the effects of larger economic policies or neighborhood conditions within the exosystem/macro system.

Overall, the ecological perspective provides a scientific understanding of how various environmental contexts interact with individual biological, cognitive, emotional, and social factors to shape human development across different lifespan stages.

Examples of Ecological Perspective

- The impact of ‘nurture’ in child development : A child’s upbringing is greatly influenced by their immediate family and caretakers (microsystem), which can include parenting style, availability of resources, and other family dynamics. Additionally, the exosystem (such as community resources and social support structures) and macrosystem (cultural values and traditions) significantly impact a child’s development (see also: nature vs nurture debate ).

- Real-life s ocial network s impact our life chances : Individuals create relationships that form complex social networks. These networks can extend beyond their microsystems to encompass mesosystems such as local communities or broader systems like groups based on shared interests.

- Workplaces affect our income and prosperity : Work environments can impact employee productivity and satisfaction in various ways, such as job demands/resources available, manager support, organization culture, etc., ultimately influencing the individual’s psychological well-being.

- The h ealthcare system affects your long-term health : The quality of healthcare services is not solely dependent on doctors but encompasses the entirety of a patient’s experience. This includes the involvement of family caregivers’ involvement and the overall operation and management of hospitals and healthcare institutions.

- Environmental stewardship affects your health : Global concern with ecology mandates us to study interactions between individuals and the natural environment that impacts them, i.e., recycling habits or transportation choices for reducing carbon footprints.

- The education system affects your job prospects : An individual’s academic success isn’t only dependent on individual intelligence or motivation but is also influenced by the surrounding educational environment. It includes school resources, curricula guidelines, or initiatives encouraging diversity and inclusion in the classroom.

- Politics & legislation affect what you can and can’t do : Political changes on a large scale, such as shifts in economic power structures or changes in international relations, can profoundly impact people’s day-to-day lives. These changes can alter various settings, from social interactions to institutional policies, and influence how individuals perceive and experience their lives over time.

- Mental health support may consider environmental factors in a support plan: Mental health professionals may integrate an ecocentric approach while working out a treatment plan for a client/patient, which considers not just individual psychopathology but also social and environmental factors that influence the person.

- Good housing and neighborhoods affect wellbeing : Built environment (housing, transportation, and amenities located nearby) can affect psychological well-being (e.g., green spaces promote activities conducive to physical exercise) and the safety of people.

Origins of Ecological Perspective in Psychology

The ecological perspective in psychology has its roots in various disciplines like biology, sociology, and anthropology . We can trace its origins to several key historical movements that emerged during the early 20th century.

One important precursor was behaviorism – an approach emphasizing observing and measuring behavior rather than unobservable mental processes such as thoughts or emotions (Holahan, 2012).

In the 1930s, psychologist James Gibson voiced criticism against traditional behaviorism, which he believed ignored the complexity of human thought processes, such as accurately perceiving objects or movement (Lobo et al., 2018).

He emphasized the importance of perception’s influence on action in determining behaviors, which led to the development of approaches based on environmental systems analysis (Lobo et al., 2018).

Kurt Lewin, another influential figure, proposed field theory, highlighting how individuals are part of a psychological environment defined by their social and cultural context (Heft, 2022).

He emphasized that cognition, both personal (internal mindset) and collective process, is heavily shaped by interactions with external environments/systems.

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory integrated these ideas by anchoring discussions within a systemic approach while developing ideas about how interactions between individuals across multiple environmental levels influence individual development.

From the viewpoint of this theory, a better understanding of transitions across different life stages requires considering individual development within a larger environmental context (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

This is because both the individual and the environment influence each other when studying mental development from birth through maturity.

These historical movements emphasized understanding how human beings interact with their environment at different levels while highlighting the significance placed on context (physical, social-cognitive-affective-cultural).

They paved the way for interdisciplinary theories such as Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory and impacted diverse areas of psychology, from lifespan development to mental health studies.

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory is a framework for understanding human development as a complex process influenced by multiple interacting environmental factors that coordinate to shape individual experiences.

The theory proposes that people must be understood in isolation and within the social and cultural contexts in which they develop (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

According to the theory, human development happens within social environments , which can be classified into several hierarchical levels such as microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem:

1. Microsystem

The microsystem refers to the closest personal environments that directly influence an individual’s experiences.

These may include family or home environments, as well as schools or peers with whom individuals interact regularly (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

Microsystem Example

The parents are the most important part of a person’s microsystem. A child’s bond with family is the first bond, and is hugely influential in developing early values and belief systems .

2. Mesosystem

Mesosystems refer to the connections between microsystems where interactions occur, such as the relationship between a child’s school and their family environment.

The quality of these interactions can be affected by how these subsystems are linked to one another, sharing mutual involvement (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

Mesosystem Example

The family and the school are perhaps the two most important microsystems that impact a child’s psycho-social development. When they interact, this is an instance of the mesosystem at work. If the family and school have a good relationship, this can greatly help a child’s development and learning.

3. Exosystem

Exosystems refer to external systems that impact individuals indirectly, such as societal norms, cultural expectations, and policies that govern institutions like government regulatory bodies or workplace regulations.

These systems can significantly impact an individual’s circumstances, even if they are not directly associated with them (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

For example, a change in government policy regarding healthcare can have a ripple effect on the healthcare services available to an individual, even if they do not work in the healthcare industry or have any direct involvement with the government.

Exosystem Example

The occupation of a child’s parent, or the changes in the parents’ occupation, are factors not directly related to the child and yet they have a major influence in shaping their selves.

4. Macrosystem

The macrosystem encompasses a society’s broad cultural and social values within a larger historical context, including religion, customs, culture, and political ideologies.

These values constantly impact policies and laws, shaping a particular culture and defining what behaviors are considered acceptable or unacceptable (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

Macrosystem Example

Different societies have different cultural norms and values that children imbibe. A child growing up in a tribal community in sub-Saharan Africa is shaped by a different macrosystem than another child growing up in an urban Scandinavian town.

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) theoretical approach accounts for how interactions at each level of the environment influence an individual’s biological, psychological, and socio-emotional development over time.

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory emphasized the interdependence of environmental systems and was sensitive to demographic and culture-specific processes influencing each level of influence.

He recognized the unique interactions among various environmental system levels that provide opportunities and challenges at different stages, leading to enhanced or maladaptive developmental outcomes (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

By understanding the complex interactions between individuals and their environments, the theory can inform interventions aimed at promoting positive development.

The Value of an Ecological Perspective

An ecological perspective is an important approach in sociology, psychology , and the social sciences as it underscores the role of environmental context in shaping individual thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

This approach highlights how both internal and external factors interact dynamically to form human development (Lobo et al., 2018).

The ecological perspective encourages using multiple research disciplines to understand humans’ complex psychological environment and behavior through a coordinated and intersectional approach.

Furthermore, the ecological perspective promotes systematic analysis, making it easier to study and understand complex systems within contexts calling for mapping out complex relationships between people and the environment (Brymer & Schweitzer, 2022).

Importantly, the ecological perspective places the person-environment relationship at its core, giving greater recognition of the importance of biological, psychosocial, and cultural factors on outcomes in people’s lives.

Therefore, the analysis takes into account the influences across various layers, emphasizing the holistic nature of an individual’s life and experiences.

Furthermore, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological perspective aims to illustrate the developmental stages over time and how various systems (such as micro, meso, exo, and macro) interact to influence them (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

It also considers the transitions, such as from adolescence to adulthood/aging, societal changes, and other crucial variables that affect life choices.

Overall, the ecological perspective enriches psychological knowledge significantly by offering a dynamic framework that considers interdependent relations between individuals and their diverse environments.

An ecological perspective is a significant psychological approach emphasizing the complex interplay between individuals and their environments.

This perspective enables researchers to understand how different environmental factors can impact an individual’s biological, psychological, and social development over time.

The significance of the ecological perspective rests on its ability to provide detailed insights into how individuals adapt to their environment as they transition through diverse developmental stages.

By considering various subsystems interacting at multiple levels – micro/ meso/ exo/ macro – valuable data that may inform public policy can be derived for addressing problems such as social inequality .

Overall, ecological perspectives continue gaining popularity among researchers worldwide due to achieving solutions-oriented approaches that facilitate the nurturement of healthy initiatives promoting improved individual outcomes.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development . New Jersey: Harvard University Press.

Brymer, E., & Schweitzer, R. D. (2022). Learning clinical skills: An ecological perspective. Advances in Health Sciences Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10115-9

Crawford, M. (2020). Ecological systems theory: Exploring the development of the theoretical framework as conceived by Bronfenbrenner. Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices , 4 (2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100170

Heft, H. (2013). An ecological approach to psychology. Review of General Psychology , 17 (2), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032928

Heft, H. (2022). Lewin’s “psychological ecology” and the boundary of the psychological domain. Philosophia Scientae , 26-3 , 189–210. https://doi.org/10.4000/philosophiascientiae.3643

Holahan, C. (2012). Environment and behavior . Springer Science & Business Media.

Lobo, L., Heras-Escribano, M., & Travieso, D. (2018). The history and philosophy of ecological psychology. Frontiers in Psychology , 9 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02228

Satchell, L. P., Kaaronen, R. O., & Latzman, R. D. (2021). An ecological approach to personality: Psychological traits as drivers and consequences of active perception. Social and Personality Psychology Compass , 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12595

- Viktoriya Sus (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Cognitive Dissonance Theory: Examples and Definition

- Viktoriya Sus (MA) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Free Enterprise Examples

- Viktoriya Sus (MA) #molongui-disabled-link 21 Sunk Costs Examples (The Fallacy Explained)

- Viktoriya Sus (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Price Floor: 15 Examples & Definition

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

It is noted that the ecological perspective shares common concepts from the systems theory, which is "the transdisciplinary study of the abstract organisation of phenomena, independent of their substance, type, or spatial or temporal scale of existence" (Heylighen and Joslyn, 1992).

Dr. Bronfenbrenner felt that "a person's development is the product of a constellation of forces-cultural, social, economic, political- and not merely psychological ones" (Fox, 2005, para 6).According to an article by Nancy Darling of Oberlin College, "Ecological Systems Theory is presented as a theory of human development in which everything is seen as interrelated and our knowledge ...

This essay will discuss the role of ecological validity in psychological research, drawing on material from the DE100 textbook 'Investigating Psychology'. It will begin by giving a description of what ecological validity is, and consider it in relation to different examples of research.

This study takes up the ecological approach for discussion and assesses its usefulness for social work practice. The ecological approach is also compared with humanism and existentialism and its various aspects are critically analysed with respect to achievement of managerialism and accountability in social work practice. Get Help With Your Essay

An ecological perspective is an important approach in sociology, psychology, and the social sciences as it underscores the role of environmental context in shaping individual thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. This approach highlights how both internal and external factors interact dynamically to form human development (Lobo et al., 2018).

The Ecological Systems theory represents a convergence of biological, psychological, and social sciences. Through the study of the ecology of human development, social scientists seek to explain ...

Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory posits that an individual's development is influenced by a series of interconnected environmental systems, ranging from the immediate surroundings (e.g., family) to broad societal structures (e.g., culture). These systems include the Microsystem, Mesosystem, Exosystem, Macrosystem, and Chronosystem, each representing different levels of environmental ...

The essay underscores the critical importance of transportation and communication technology to the shaping of the human ecological system. Human Ecology brings concision and elegance to this holistic perspective and will serve as a point of reference and orientation for anyone interested in the powers and scope of the ecological approach.

As discussed previous, Germain (1973) was a key writer within the ecological approach findings.The work of Bronfenbrenner is central to his work along with Gitterman (1995) who state, "ecological thinking is less concerned with cause and is more concerned with the exchange between A and B, and how to help modify maladaptive exchanges" An ...

Essay Example: Introduction So, human development is kinda like this big, complicated puzzle. Lots of things play a part, from who you are as a person to the bigger world around you. One smart guy, Urie Bronfenbrenner, came up with this theory called the Ecological Systems Theory. It's pretty