- Open access

- Published: 26 August 2024

Jordanian nursing students’ experience of harassment in clinical care settings

- Arwa Masadeh 1 ,

- Rula Al-Rimawi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7486-0957 2 ,

- Aziza Salem ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9402-9282 3 &

- Rami Masa’deh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2762-7375 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 587 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

47 Accesses

Metrics details

Introduction

Nursing students experienced various types of bullying and abuse in their practice areas. This study aims to assess the incidence, nature, and types of bullying and harassment experienced by Jordanian nursing students in clinical areas.

Methodology

A cross-sectional, descriptive design was used, utilizing a self-report questionnaire. A convenient sampling technique was used to approach nursing students who are in their 3rd or 4th year in governmental and private universities.

Of 162 (70%) students who reported harassment, more than 80% of them were females and single. Almost 40% of them reported that males were the gender of the perpetrator. Almost 26.5% of them reported that patient’s relatives or friends were the sources of harassment. Psychological/verbal harassment was the most reported type of harassment (79%). Findings showed that there was a statistically significant difference in psychological/verbal harassment based on gender and type of the university. Also, there were significant negative correlations between psychological/verbal harassment, professional achievement, and personal life.

Harassment in the clinical area is affecting the professional and personal lives of students, who lack the knowledge of policy to report this harassment.

Key messages

1. Most of the students who reported harassment were females and single.

2. Psychological/verbal harassment was the most reported type of harassment.

3. Psychological/verbal harassment affected the students’ professional and personal achievements.

Peer Review reports

The healthcare sector is one of the most subjected sectors to violence among all sectors. Between 8 and 38% of healthcare providers exposed to workplace violence (WPV) in their career [ 1 ]. Nationally, the chief of the Jordan Medical Association declared that about 10 attacks on healthcare workers are recorded every month [ 2 ]. Among all healthcare workers, nurses and physicians are the most vulnerable personnel to WPV [ 3 , 4 ], as nurses have more contact with patients and their families or relatives.

Not only nurses are susceptible to WPV, but nursing students also are subjected to various types of violence, bullying, and harassment in their practice areas [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. The prevalence of bullying among nursing students varies based on many factors. There were significant variations in the prevalence of bullying among nursing students, ranging from 9 to 96%, according to an integrative literature review that included 30 articles and examined the issue in addition to other factors [ 10 ]. In Australia, a study reported that half of 888 nursing students experienced bullying in the last year [ 6 ]. Similarly, an Omani study found that 53.4% of 118 nursing students experienced at least one incident of bullying during their practice period [ 5 ].

Nursing students experienced various types of bullying and abuse in their practice areas including verbal, emotional, physical, sexual, and racial abuse [ 5 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. The most common form of abuse nursing students experienced was verbal abuse [ 6 , 8 , 12 ]. Students are mostly bullied by other nursing or medical students, nurses, physicians, other healthcare teams, school faculty, or their instructor [ 15 ], patients or their families [ 6 , 8 , 11 , 12 ], other hospital workers [ 6 ].

All forms of bullying and harassment have negative consequences on students, personally, physically, and emotionally; they might feel anxiety [ 12 , 16 , 17 , 18 ], sickness, low self-esteem [ 12 , 17 , 18 ], anger [ 12 , 17 , 19 ], fear, depression [ 12 , 15 , 19 ]. Additionally, bullying and harassment have an impact on students’ performance; they may cause them to be hesitant to visit clinical areas, doubt the quality of care they provide because it undermines their confidence, or reconsider their careers as nurses [ 5 , 6 , 12 , 15 , 19 ].

With all the negative consequences of bullying, most nursing students don’t report the incidents of bullying they have experienced [ 6 , 11 , 13 , 20 ]. Many students consider it to be part of the nursing profession [ 6 , 11 ], i.e. the “normalization” of bullying and violence [ 13 ]. Other students hated to be seen as victims [ 6 ], and others think that even if they reported the harassment, no action would be taken [ 6 , 20 ].

There is little known about nursing students’ experience, consequences, and reporting of bullying and harassment. Based on the literature review, there are many Jordanian studies on violence against nurses, but there is no published study investigating nursing students’ experience of bullying and harassment in Jordan, [ 21 ]. This study aims to assess the incidence, nature, and types of bullying and harassment experienced by Jordanian nursing students in clinical areas.

Materials and methods

Utilizing a self-report questionnaire, a cross-sectional, descriptive design was used, as very little is known about bullying and harassment of nursing students in Jordan.

The study was conducted at Nursing Faculties in five governmental and five private universities. Governmental universities are located in the north, middle, and south of Jordan. Four of them have the largest number of nursing students among all governmental and private universities. Three private universities are located in the Capital and two are in the north of Jordan. There are very few private universities outside the Capital. Approached private universities have the largest number of nursing students among all private universities.

Non probability, convenient sampling technique was used. We approached nursing students who met the inclusion criteria: who were in their 3rd or 4th year of study and willing to participate. The sample size was determined based on Cohen power primer [ 22 ]. Using a conventional power of 0.8, medium effect size of 0.25, level of significance of 0.05, and Pearson Correlation, the minimum sample size would be 134. Using G-power 3.1.9.2, and using the power of 0.8, medium effect size (0.25), and level of significance of 0.05 and Pearson r, the minimum total sample size would be 138 [ 23 ].

The questionnaire in the current study was adapted from Hewett [ 24 ]. The questionnaire consists of six parts, including (a) demographic (including Age, Gender, Marital Status, and Wearing Hijab for females) and educational data (including Year of Study, Type of Program, and University type), (b) verbal (12 items), physical (8 items), and sexual harassment (6 items) in clinical areas, (c) data about the perpetrator (12 items) and the settings (3 items) where the harassment occurred, (d) impact of harassment on personal life (8 items) and professional achievement (5 items), (e) reporting of harassment in clinical areas (one question about if the student reported the harassment or not and 6 items about the reason behind not-reporting the incident), and (f) management of violence in clinical areas (one open-ended question). The tool consists of 67 items; each item rated the occurrence of harassment or the impact of harassment on a four-point Likert scale (0 ―Never to 3 – Often: more than 5 times). Items about reporting the harassment were yes or no questions. The internal consistency of the questionnaire revealed Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88. Originally, the tool was developed in English. It was translated in compliance with WHO translation guidelines [ 25 ]. Community health and mental health nursing professionals evaluated the questionnaire after it had been translated and before the pilot study was carried out to ensure the study instruments’ content validity. The research process - from distributing questionnaires to receiving data - was tested, and no problems were found.

Data collection

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Applied Science Private University’ committees, the principal investigator approached the deans of Nursing Faculties and explained the study’s purpose and procedure. Then, a poster about the study with a barcode of the online questionnaire was displayed in the hall of all nursing faculties. The participant read the cover letter before filling out the questionnaire, which explained the purpose of the study, the role of the participants, their right to withdraw from the study, and all their information would be anonymous and confidential.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approvals from the Applied Science Private University as well as from all other participating universities were obtained before commencing the research. Besides, this research was conducted under the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 25). The study sample and their responses were described using descriptive statistics. Differences in participants’ scores based on their characteristics were assessed by running a series of t-tests. Further, Pearson coefficient was used to detect relationships between the participants’ characteristics and harassment scores.

In this study, 268 nursing students were approached, 244 consented and 230 of them fully completed and returned the questionnaires; those were involved in the final analysis. All nursing students involved in this study have attended at least one clinical placement course and were either in their third or fourth year of study. Data was divided into two groups (i.e. group one: students who reported facing harassment; and group two: students who did not report any type of harassment).

Description of the participants

Table 1 shows the characteristics of nursing students based on the occurrence of harassment. Concerning the total participated nursing students (the two groups), approximately, 70% ( N = 162) of them reported that they faced harassment. Female students formed almost 80% of the overall sample. Most of the students were single with a mean age of 22.37 ± 3.156. Participated students were enrolled in the university either in the regular program or bridging program with almost half of the students from governmental universities and half of them from private universities.

Regarding the group of students who reported harassment (i.e. group one), more than 80% ( N = 182) of them were females and single. Almost 40% ( N = 65) of them reported that males were the gender of the perpetrator. Nursing students were asked about the source of harassment and almost 20% ( N = 33) of them showed that doctors were the sources of harassment, 17.9% ( N = 29) reported that patients were the source of harassment, 37.7% ( N = 61) were patients relatives or friends and 19.8% ( N = 32) administrative staff were the source of harassment. Almost two-thirds 66% ( N = 107) of those who stated they were harassed didn’t know about the policy of reporting harassment. Psychological/verbal harassment was the most reported type of harassment, representing approximately 79% ( N = 142) of those reported harassment.

The difference in harassment based on the characteristics of the participants

Several independent sample t-tests were conducted to examine the difference in psychological/verbal harassment; physical harassment, and sexual harassment based on the gender of the student, marital status, type of the university, type of the program, and previous work experience. These statistical tests were only conducted for students who reported the occurrence of harassment (group one). Findings showed that there were no statistical differences in physical and sexual harassment based on all previous variables.

About psychological/verbal harassment, Table 2 shows that there was a statistically significant difference in psychological/verbal harassment based on gender and type of the university. Female students reported significantly higher levels of psychological/verbal harassment (M = 22.14, SD = 7.29) than male students (M = 19.31, SD = 4.74); t (60.976) = -2.61, p-value 0.011. Eta squared was 0.04 indicating that the magnitude of the difference was small. Moreover, students from private universities reported significantly higher levels of psychological/verbal harassment (M = 22.60, SD = 7.06) than those from governmental universities (M = 20.42, SD = 6.73); t (155.086) = -2.008, p-value 0.046. Eta squared was 0.024 indicating that the magnitude of the difference was small. There were no statistical differences in psychological/verbal harassment based on marital status, type of the program, and previous work experience.

The correlation between psychological/verbal harassment, professional achievement, personal life, and age of nursing students

Pearson r product-moment correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationship between psychological/verbal harassment, professional achievement, personal life, and age of nursing students. Table 3 shows that there were statistically significant moderate negative correlations between psychological/verbal harassment, professional achievement, and personal life ( r =-0.437, p-value < 0.001; r =-0.566, p-value < 0.001, respectively). An increase in psychological/verbal harassment was significantly associated with a decrease in the professional achievement and personal life of the students. The R-squared between psychological/verbal harassment, and professional achievement is 0.19 indicating that almost 19% of the change in the variance of professional achievement is explained by psychological/verbal harassment. Again, the R-squared between psychological/verbal harassment and personal life is 0.32 indicating that almost 32% of the change in the variance of personal life is explained by psychological/verbal harassment. However, findings showed that there was no significant correlation between age and psychological/verbal harassment.

Nursing students spend around 20 h weekly in the clinical area after the first year. They are on the first line of encounter not only with patients and their relatives, but also with nurses, physicians, and other health team members. The study reveals that 70% ( n = 162) of students in the sample were subjected to one or more types of harassment, which is considered a little bit lower than what was reported by Abd El Rahman and Mabrouk [ 17 ] who conducted their research in Egypt found that (88%) of the sample faced bullying during their clinical rotation. On the other hand, this result is higher than the Omani study which found that 53.4% of students experienced harassment at least once throughout their clinical rotation [ 5 ]. Also, it was higher than what was reported by Birks and colleagues; who compared Australian and British students and found that (50.1%) and (35.5%) respectively, were bullied among students in their sample [ 26 ]. Additionally, it was higher than a New Zealand study which revealed that 40% of students experienced harassment in clinical areas [ 16 ]. A higher percentage of bullying among nursing students could be attributed to underestimating student’s knowledge, skills, and experiences.

The study revealed that most of the bullied students (80%) were females. This is not strange as the majority of the sample were female too. These results are comparable with an Omani study [ 27 ]. However, a study found that Australian females were subjected to harassment more than male students, while this was not the case for British students [ 26 ]. Over the world, the nursing profession is considered a female profession; this could be the case because females are more compassionate and capable to care of people in health and sickness.

The study revealed that 40% of the reported gender of perpetrators were males. This was inconsistent with what was found by Palaz, who found that the majority of perpetrators were females (92.4%) [ 28 ]. Whereas, the perpetrators in the current study were 26.5% patient’s relatives or friends, 20% doctors, 18% patients, and 13.9% administrative staff. Omani study found that patients (42.3%) and their relatives (33.9%) were the major perpetrators, followed by other healthcare teams (31.4%), doctors (28%), and registered nurses (26%) [ 5 ]. Whereas, the key perpetrators of verbal abuse in Hong Kong were patients (66.8%), followed by hospital staff (29.7%), university supervisors (13.4%), and patients’ relatives (13.2%) [ 29 ]. The students have to contact with different individuals with varying educational backgrounds, cultural backgrounds, ethical perspectives, and value systems. However, many students have low self-esteem and limited communication skills, especially in clinical settings, as they are considered new and stressful areas [ 5 ].

Despite the large number of harassed nursing students, two-thirds of them don’t know about reporting harassment policy (66%). This was very close to a study conducted in Oman that found victims of harassment were unaware of any regulations against harassment in in college (60.2%) or clinical areas (65.2%) [ 11 ]. On the other hand, 36% of students in the current study reported that they didn’t report any incident as nothing would be done. Budden and colleagues reported that many participants knew about such policies, whether in the university (65.5%) or clinical settings (69%). Despite students’ knowledge of policies, these were not clear, they feared being mistreated, thought that nothing would be done if reported, didn’t know how and where to report, thought that the incidence was not significant to report [ 6 ], and the most frightening idea is that harassment is considered a normal part of the job [ 6 , 11 , 26 ].

The current study revealed that most students 79% reported subjecting to psychological/verbal harassment. This result supports the previous studies conducted worldwide; such as 60% in Turkey [ 28 ], 73.3% in Iran [ 30 ], and 55% in Saudi Arabia [ 31 ]. Although a smaller percentage was reported for verbal harassment in Hong Kong (30.6%), it was higher than that for physical abuse (16.5%) [ 29 ]. Nursing students weren’t subject to physical harassment, they were subjected to psychological/verbal harassment or sexual harassment as gestures without reaching the point of physical harassment. Also, the perpetrator is subjected more to legal liability for this type of harassment.

Sexual harassment was reported only in 2.5% of nursing students in the current study, this result was less than what was reported by Tollstern and colleagues, who found that 9.6% of respondents training at a local hospital in Tanzania reported subjecting to sexual harassment [ 32 ]. Also, the results of a Chinese meta-analysis revealed that the incidence of sexual harassment among female nursing students was 7.2% [ 33 ]. On the other hand, a shocking high result of sexual harassment was reported in Korea, where it was found that 50.8% of the participants faced sexual harassment. The sexual harassment was reported as gender-linked harassment; as 98% of perpetrators were male [ 34 ]. Closing one’s way, touching one’s body on purpose, and attempting to have sex, all these fluctuating behaviors in reported sexual harassment might be related to cultural, religious, and behavioral differences between countries [ 32 ]. Furthermore, an integrative review revealed that sexual harassment among nursing students is exacerbated by near body contact care role of nursing, the perceptions of societies toward nursing as a women’s profession, the sexualization of nurses, and the imbalances in the workplace [ 35 ]. In our society, we are governed by customs and traditions emanating from our Islamic religion. Therefore, compared to other studies, the frequency of sexual harassment in the current study is considered very low.

Although our finding revealed no statistical differences in sexual harassment based on all variables in the study including gender, this could be connected to the low incidence of sexual harassment in the current study. However, the systematic review and other studies worldwide revealed that female nurses are facing a high prevalence of sexual harassment [ 35 , 36 , 37 ].

On the contrary to what was reported by Budden and colleagues and Cheung and colleagues, our results revealed a statistically significant difference in psychological/verbal harassment based on the gender and type of the university [ 6 , 29 ]. This could be related to the fact that the sample consisted primarily of female students. Students at private universities reported much higher levels of verbal and psychological harassment than those at governmental universities. These governmental universities are located in areas considered conservative compared to those where private universities are located.

The current study found significant moderate negative correlations between psychological/verbal harassment, professional achievement, and personal life. Professional achievement and personal life tend to decrease as verbal harassment increases. These results are not surprising and are supported by what was found in a Chinese study, which reported a significant increase in sick leave taken after verbal abuse that lasted to ten days. Furthermore, the researchers revealed the presence of a significant negative effect of verbal harassment on personal feelings, clinical performances, and the extent to which they were disturbed by verbal harassment [ 29 ]. In the same context, Amoo and colleagues revealed that bullying caused a loss of confidence and the occurrence of stress and anxiety among nursing students [ 7 ].

Implications

The current study showed that most of the students who were subjected to harassment didn’t know that there was a policy that addressed this problem. Nursing faculty, health organizational administration, and nursing instructors are responsible for implementing strategies that will end the sequence of all types of harassment and promote a healthy work environment through; improving students’ communication skills, empowering them, establishing and planning goal-directed training programs related to harassment and harassment prevention in clinical area for nursing students before starting their training. Also, it is very important to teach students that harassment should never be tolerated, no matter how it manifests or where it comes from.

The nursing curriculum must be updated to add new topics such as communication skills, and how to deal with perpetrators of different types of harassment. Moreover, the clinical area must have clear policies regarding reporting harassment which should be declared to students. Furthermore, studies are needed regarding the psychological effects of harassment, and how to deal with the psychological effects, to help student manage their fears and negative feelings related to harassment. The literature indicated that many nurses quit or change careers as a result of harassment, so it’s critical to focus on adapting to a zero-harassment environment [ 38 , 39 ].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include recruiting samples from all geographical areas in Jordan; north, middle, and south, and from governmental and private universities. Despite the strengths of this study, its results should be considering its limitations. There were not enough male students in the sample; further study may adequately recruit male students. Another limitation is not including nationality in the questionnaire, so generalization to all Arabic or other students might be limited. Therefore, it is recommended to replicate this study among various Arabic populations.

This study indicates that harassment is a significant issue among Jordanian nursing students. Nursing students face different types of harassment all over the journey of clinical training. Results showed a high prevalence of psychological/ verbal abuse that affected the professional and personal lives of students. Despite the high incidence of harassment among nursing students, most students have not reported the harassment officially as they lack the knowledge of how to report this harassment or are not aware of the presence of policies regarding harassment, highlighting the importance of providing education to increase their awareness about such policies. The study highlights the role of universities in developing training programs and policies, if none, to prevent harassment in clinical areas and manage the effect of harassment among students. This will contribute in creating a safe, healthy, and supportive educational environment for nursing students.

Data availability

Data cannot be shared openly but are available on request from authors.

WHO. Preventing violence against health workers: World Health Organization. 2022. https://www.who.int/activities/preventing-violence-against-health-workers .

Why Physicians. and Nurses are Attacked? Jordan News. 2022.

Bernardes MLG, Karino ME, Martins JT, Okubo CVC, Galdino MJQ, Moreira AAO. Workplace violence among nursing professionals. Revista Brasileira De Med do Trabalho. 2020;18(3):250.

Article Google Scholar

Liu J, Gan Y, Jiang H, Li L, Dwyer R, Lu K, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(12):927–37.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Qutishat MG, Kannekanti S. Bullying and harassment perceived by undergraduate nursing students in clinical settings, and its implication to academic strategies and interventions. J Health Sci Nurs. 2019;4(9):56–62.

Google Scholar

Budden LM, Birks M, Cant R, Bagley T, Park T. Australian nursing students’ experience of bullying and/or harassment during clinical placement. Collegian. 2017;24(2):125–33.

Amoo SA, Menlah A, Garti I, Appiah EO. Bullying in the clinical setting: lived experiences of nursing students in the Central Region of Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0257620.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Samadzadeh S, Aghamohammadi M. Violence against nursing students in the workplace: an Iranian experience. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2018;15(1).

Jafarian-Amiri SR, Zabihi A, Qalehsari MQ. The challenges of supporting nursing students in clinical education. J Educ Health Promotion. 2020;9:216.

Fernández-Gutiérrez L, Mosteiro‐Díaz MP. Bullying in nursing students: a integrative literature review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(4):821–33.

Qutishat MG. Underreporting bullying and harassment perceived by undergraduate nursing students: a descriptive correlation study. Int J Mental Health Psychiatry. 2019;5(1).

Özcan NK, Bilgin H, Tülek Z, BOYACIOĞLU NE. Nursing Students’ Experiences of Violence: A Questionnaire Survey. J Psychiatric Nursing/Psikiyatri Hemsireleri Dernegi. 2014;5(1).

Hallett N, Wagstaff C, Barlow T. Nursing students’ experiences of violence and aggression: a mixed-methods study. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;105:105024.

Ehsani M, Farzi S, Farzi F, Babaei S, Heidari Z, Mohammadi F. Nursing students and faculty perception of academic incivility: a descriptive qualitative study. J Educ Health Promotion. 2023;12(1):44.

Baraz S, Memarian R, Vanaki Z. Learning challenges of nursing students in clinical environments: a qualitative study in Iran. J Educ Health Promotion. 2015;4(1):52.

Minton C, Birks M, Cant R, Budden LM. New Zealand nursing students’ experience of bullying/harassment while on clinical placement: a cross-sectional survey. Collegian. 2018;25(6):583–9.

Abd El Rahman RM. Perception of student nurses’ bullying behaviors and coping strategies used in clinical settings. 2014.

Birks M, Budden LM, Biedermann N, Park T, Chapman Y. A ‘rite of passage?’: bullying experiences of nursing students in Australia. Collegian. 2018;25(1):45–50.

Hashim N, Aziz HAM, Amran MAA, Azmi ZN. Bullying among nursing students in UiTM Puncak Alam during Clinical Placement. Environment-Behaviour Proc J. 2020;5(15):49–55.

Albakoor FA, El-Gueneidy MM, El-Fouly OM. Relationship between coping strategies, bullying behaviors and nursing students’ self esteem. Alexandria Sci Nurs J. 2020;22(1):47–58.

Jordanian Database for Nursing Research Jordan: School of Nursing, The University of Jordan. 2017. http://jdnr.ju.edu.jo/home.aspx .

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Faul F. G*Power. 3.1.9.2 ed. Germany2014. p. Statistical Power Analysis Program.

Hewett D. Workplace violence targeting student nurses in the clinical areas: Stellenbosch. University of Stellenbosch; 2010.

WHO. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Birks M, Cant RP, Budden LM, Russell-Westhead M, Özçetin YSÜ, Tee S. Uncovering degrees of workplace bullying: a comparison of baccalaureate nursing students’ experiences during clinical placement in Australia and the UK. Nurse Educ Pract. 2017;25:14–21.

Qutishat MEGM. Bullying and harassment perceived by undergraduate nursing students in clinical settings and its implication to academic strategies and interventions. J Health Sci Nurs. 2019;9(4).

Palaz S. Turkish nursing students’ perceptions and experiences of bullying behavior in nursing education. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2013;3(1):23.

Cheung K, Ching SS, Cheng SHN, Ho SSM. Prevalence and impact of clinical violence towards nursing students in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 2019;9(5):e027385.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Samadzadeh S, Aghamohammadi M. Violence against nursing students in the workplace: an Iranian experience. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2018;15(1):20160058.

Shdaifat EA, AlAmer MM, Jamama AA. Verbal abuse and psychological disorders among nursing student interns in KSA. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2020;15(1):66–74.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tollstern Landin T, Melin T, Mark Kimaka V, Hallberg D, Kidayi P, Machange R, et al. Sexual harassment in clinical Practice—A cross-sectional study among nurses and nursing students in Sub-saharan Africa. SAGE Open Nurs. 2020;6:2377960820963764.

Zeng LN, Zong QQ, Zhang JW, Lu L, An FR, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of sexual harassment of nurses and nursing students in China: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15(4):749–56.

Kim TI, Kwon YJ, Kim MJ. Experience and perception of sexual harassment during the clinical practice and self-esteem among nursing students. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2017;23(1):21–32.

Smith E, Gullick J, Perez D, Einboden R. A peek behind the curtain: an integrative review of sexual harassment of nursing students on clinical placement. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(5–6):666–87.

Kahsay WG, Negarandeh R, Dehghan Nayeri N, Hasanpour M. Sexual harassment against female nurses: a systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2020;19(1):58.

Maghraby RA, Elgibaly O, El-Gazzar AF. Workplace sexual harassment among nurses of a university hospital in Egypt. Sex Reproductive Healthcare: Official J Swed Association Midwives. 2020;25:100519.

Yeh T-F, Chang Y-C, Feng W-H, sclerosis, Yang M. C-C. Effect of Workplace Violence on Turnover Intention: The Mediating Roles of Job Control, Psychological Demands, and Social Support. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 2020;57:0046958020969313.

Hollowell A. Violence affects nursing recruitment, retention, NNU report finds. USA: National Nurses United; 2024.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Applied Science Private University for supporting this study. Also, the authors thank the participants and the deans of the nursing faculties.

Not Applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Nursing, Applied Science Private University, Amman, 11937, Jordan

Arwa Masadeh & Rami Masa’deh

Nursing College, Al-Balqa Applied University, Salt, Jordan

Rula Al-Rimawi

Nursing Department, University of Tabuk, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia

Aziza Salem

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Concepts: A.M. & R.M Design: A.M. & R.M Definition of intellectual content: A.M. & R.M Literature search: A.M. & R.R. Data acquisition: A.M. & R.M Data analysis: A.M. & R.M Statistical analysis: R.M. Manuscript preparation: A.M. & A.S Manuscript editing: A.M. & A.S Manuscript review: A.M. & A.S & R.F.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rami Masa’deh .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

IRB approval was obtained from the IRB committee in Applied Science Private University (2021-2022-5-1). The principal investigator posted a poster about the study with a barcode of the online questionnaire in the hall of all nursing faculties. The participant read the cover letter before filling out the questionnaire, which explained the purpose of the study, the role of the participants, their right to withdraw from the study, and all their information would be anonymous and confidential. Filling out the questionnaire was considered as a consent form. So, informed consent was obtained implicitly from all subjects.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable (as explained before).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Masadeh, A., Al-Rimawi, R., Salem, A. et al. Jordanian nursing students’ experience of harassment in clinical care settings. BMC Nurs 23 , 587 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02146-x

Download citation

Received : 24 May 2024

Accepted : 02 July 2024

Published : 26 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02146-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Psychological harassment

- Physical harassment

- Sexual harassment

- Personal Life

- Professional Achievement

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 31 March 2023

Education program promoting report of elder abuse by nursing students: a pilot study

- Dahye Park 1 &

- Jeongmin Ha 2

BMC Geriatrics volume 23 , Article number: 204 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1851 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Elder abuse is an important public health concern that requires urgent attention. One main barrier to active responses to elder abuse in clinical settings is a low level of relevant knowledge among nurses. This study aims to develop an educational program to promote an intent to report elder abuse among nursing students and assess its effectiveness, with a focus on the rights of older adults.

A mixed method design was used with the Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate model. Twenty-five nursing students from Chungbuk Province participated in the study. Attitude toward older adults and knowledge of, awareness of, attitude towards, and intent to report elder abuse were assessed quantitatively and analyzed using paired t-test. The feasibility of the program and feedback were collected qualitatively through group interviews and analyzed using content analysis.

After the education program, attitude toward older adults (Cohen’s d = 1.08), knowledge of (Cohen’s d = 2.15), awareness of (Cohen’s d = 1.56), attitude towards (Cohen’s d = 1.85), and intent to report elder abuse (Cohen’s d = 2.78) increased, confirming the positive effects of this program. Overall, all participants were satisfied with the contents and method of the program.

Conclusions

The method of program delivery should be improved and tailored strategies to boost program engagement among nursing students should be explored to implement and disseminate the program.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Elder abuse is an important public health concern with serious social, economic, and health consequences [ 1 ]. In Korea, a 2011 survey of 10,674 older adults aged 65 years and above showed that 12.6%—about one out of every eight older adults—suffered abuse [ 2 ]. Moreover, although recent surveys on elder abuse are unavailable, considering the rise in the incidence of elder abuse during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in the United States [ 3 ], the incidence of elder abuse in Korea may have also increased.

In clinical practice, nurses are likely to witness or predict elder abuse as their work involves a careful observation of patients’ daily lives, which provides them with an opportunity to detect, treat, and prevent elder abuse [ 4 ]. However, nurses do not actively intervene or connect older adults suffering from abuse to relevant intervention programs, despite having opportunities [ 5 ]. This is because of severe barriers to active reporting of elder abuse (e.g., invisibility and caregiver risk factors are common) [ 6 ]. Indeed, the number of reports of elder abuse by mandated reporters in 2021 was only 860 out of 7,634—a decline of 8.4% from the 939 reported cases of elder abuse by mandated reporters in 2020 [ 7 ].

In most autonomous districts in Korea, visiting nurses provide care to older adults belonging to vulnerable groups in the community [ 8 ]. Visiting nurses can determine whether the environment is safe to prevent elder abuse, which is easily concealed in the community, and have the opportunity to detect elder abuse early [ 9 ]. However, Korean nurses’ awareness of elder abuse was lower than that of other occupational groups such as nursing care workers and paramedics [ 9 ]. As Korean nurses’ awareness of elder abuse was low, there is a great possibility that on witnessing elder abuse while on duty they may not recognize it or cope with it effectively [ 9 ].

Nurses’ understanding of elder abuse is an important factor for active responses to elder abuse in a clinical setting. However, nursing students in Korea display poor knowledge on elder abuse [ 10 ]. A previous study that investigated Korean nursing students’ elder abuse-related educational needs exploring the difference between the levels of importance and performance using the IPA analysis found that the highest priority knowledge set that must be urgently improved included topics of adults’ physical and emotional changes, sexual abuse, legal punishment for elder abuse, roles of mandated reporters, roles of older adult protection agencies and shelters for elder abuse victims, encouragement of reporting and hotline, and process following abuse reporting [ 4 ]. Furthermore, topics comprising the second priority group of knowledge set that must be gradually improved consisted of human rights for older adults, roles of mandated reporters for protecting older adults’ rights, roles for prevention, verbal abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, and abandonment [ 4 ].

Data showing that professional knowledge about elder abuse is a potent antecedent to reporting elder abuse [ 5 ] highlights the need for a systematic educational program for nursing students in Korea, including expert knowledge about elder abuse, reporting of abuse, and legal and ethical grounds. However, studies that have developed and implemented elder abuse-related educational programs for nursing students in Korea are limited. This study aims to develop an educational program for promoting the intent to report elder abuse among nursing students and assess its effectiveness using the Reach, Efficacy of program under optimal conditions (i.e., intervention study), Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) framework, an approach frequently mentioned in implementation and dissemination research [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. We sought to assess the first two out of five elements of the framework: (1) to promote intent to report elder abuse incidents and to investigate the effects of the education program on attitude toward older adults, knowledge of, awareness of, attitude towards, and intent to report elder abuse; (2) to collect feedback from users through group interviews and analyze the feedback using content analysis to improve the feasibility of the program.

Study design

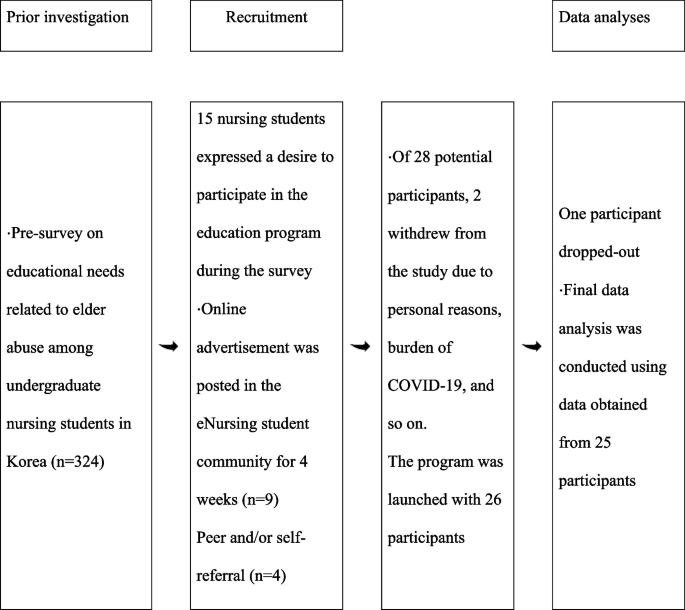

This pilot study aims to develop an education program for promoting intent to report elder abuse incidents among nursing students and to examine the feasibility of the program nationwide. After developing the program, we used a mixed method design to collect baseline data to pivot the program for effective adoption in practice (Fig. 1 ). We used one group pretest–posttest design in this pilot study to develop and assess the educational program, aiming to improve intent to report elder abuse among nursing students.

The process of participant recruitment

Study participants

Nursing students were set as the study population and the only eligibility criterion was the ability to participate in four sessions of education provided on an offline platform over two months. There were no other criteria, including age and gender. There are no established standards for sample determination for pilot studies. Thus, we determined our sample size with reference to the previous findings that suggested the optimal sample size to be 10–30 participants with the same characteristics as the targeted study population [ 11 , 14 ]. In consideration of four sessions of education over a period of two months, we recruited 28 nursing students for this pilot study.

Figure 1 shows the participant recruitment process. First, in the preliminary study on the educational needs for elder abuse among nursing students, we advertised the elder abuse-related education program and asked students who were interested to leave their phone numbers. Of 324 survey respondents, 15 showed interest in the program and left their phone numbers.

Next, we posted an advertisement on an online bulletin board for nursing students for four weeks from September 3, 2020, to October 3, 2020, and nine nursing students showed interest in participating in the study. Four students were additionally recruited through peer and self-referral. However, 2 of 28 nursing students who showed interest in the study withdrew their decision to participate in the study during the informed consent process either for personal reasons or due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at S University (IRB No S**-2020–08-011). The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, voluntary participation, freedom to withdraw from the study, guarantee of anonymity, and use of collected data for only research purposes, and written consent was obtained after confirming that the participants have accurately understood the purpose, procedure, and method of the study using the talk-back method.

Study procedure

Development of education program.

The education program used as the intervention in this study was developed based on the Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate model, a widely used generic model for instructional design [ 15 ]. This model comprises five steps: analysis, designing, development, implementation, evaluation as shown in Table 1 .

Implementation of the education program

A 240-min offline education program developed by the researchers for nursing students was provided over four Saturday sessions. The details of the program are shown in Table 2 . This program’s design differed from existing programs as it not only comprised frontal teaching, but also more participative methods, such as brain writing. Brain writing, a teaching and learning method known to effectively collect ideas and solve problems, was applied. The contents included in this program were: understanding of older adults’ rights and abuse, definition and types of elder abuse, current status and laws pertinent to elder abuse, professional older adult protective agencies, and tips for reporting elder abuse.

Instruments

Before beginning offline education, we administered a survey to examine participants’ attitudes toward older adults, knowledge of, awareness of, attitude towards, and intent to report elder abuse. The same survey was administered immediately after the program was completed. Furthermore, group interviews were conducted using semi-structured questions after education to obtain feedback about the program and improve its feasibility.

Attitude toward older adults

Attitude toward older adults was measured using the Semantic Differential Scaling developed by Sanders et al. [ 16 ] and adapted by Im [ 17 ]. This instrument comprises 20 pairs of contradictory adjectives, and each adjective pair is rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = very negative, 7 = very positive). In a previous study, seven items (#1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 15, 18) were reverse coded to maintain consistency in scoring. The average score of 20 items was used; a higher score indicated a positive attitude toward older adults, with a score of 3.5–4.5 indicating a neutral attitude [ 16 ]. The reliability (Cronbach's α) of the scale was 0.90 at the time of development, 0.82 in the study by Im [ 17 ], 0.80 at the baseline, and 0.82 at the post-test in this study.

Knowledge about elder abuse reporting

Knowledge about elder abuse reporting was measured using a 12-item questionnaire. The first author developed this questionnaire based on previous studies and the Welfare of the Senior Citizens Act, which includes the regulations for punishment for elder abuse (Article 55–2, 3, 4; Article 57), duty and procedure of elder abuse reporting (Article 39–6), and older adult protective agencies (Article 39–5). The questionnaire comprised two items for definition (concept and type), five items for law (mandated reporter and organizations), and five items for system (reporting organization and process). Participants were asked to check “I don’t know” or “I am well aware of it,” which were scored as 0 and 1, respectively. The total possible score for knowledge about elder abuse reporting ranged from 0–12, and a higher score indicated a greater level of knowledge. The Cronbach’s α was 0.77 at the baseline and 0.82 at the post-test in this study.

Awareness of elder abuse

Awareness of elder abuse offences was measured using 12 scenarios developed by Moon and Williams [ 18 ] and translated and adapted in Korea by Yoo and Kim [ 19 ]. The 12 scenarios are divided into five domains: physical abuse, emotional abuse, financial abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect. Specifically, there were three physical abuse scenarios (scenarios 1, 3, 4), four emotional abuse scenarios (scenarios 2, 5, 6, 10), two financial abuse scenarios (scenarios 8, 11), two neglect scenarios (scenarios 7, 9), and one sexual abuse scenario (scenario 12). Each scenario was rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 “This is not an abuse” to 5 “This is a very serious abuse.” The mean overall score and scores by domain were used. The total score ranged from 12–60, and a higher score indicated greater awareness of elder abuse. The reliability (Cronbach’s α) score was 0.77 in the study by Yoo and Kim [ 19 ], 0.66 at the baseline, and 0.72 at the post-test in this study.

Attitude toward elder abuse

Attitude toward elder abuse was measured using the tool developed for older adults by Cho [ 20 ]. This 25-item tool comprises fourteen items for attitude, four items for subjective norms, and seven items for perceived behavioral control. Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale (1 “strongly disagree,” 2 “disagree,” 3 “agree,” 4 “strongly agree”), with a higher score indicating more positive attitude toward intervening in the situation. Some examples of the items for attitude include “If I report an elder abuse incident, the organization that receives the report will take necessary actions,” and “Intervening in elder abuse will be helpful for the older adult involved.” There were four items for subjective norms, but two items pertinent to coworkers and head nurse were deleted because our participants were students. The scores rated on a four-point scale were summed. Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.77 for attitude, 0.74 for subjective norms, and 0.73 for perceived behavioral control in a previous study, and 0.72 for the baseline and 0.84 for the post-test in this study.

Intent to report

Intent to report was assessed by having the participants answer yes (1) or no (0) to the question asking whether they will report each of the 12 hypothetical scenarios presented earlier. The total score was calculated by summing the score for 12 scenarios [ 18 ]. Cronbach’s α was 0.64 at the baseline and 0.68 at the post-test in this study.

Group interview to obtain feedback for elder abuse education program

At the end of the program, a group interview was conducted using semi-structured questions to collect feedback on the 4-week program. The three semi-structured questions used were: “What motivated you to participate in the program?”; “What were some of the positive experiences and difficulties you faced while participating in the program?”; “What should the researchers consider when revising the education program for nursing students?”.

Data collection and analysis

The data were collected between September 3, 2020, and April 31, 2021. Of the 28 nursing students who showed interest to participate in the study, 26 were enrolled in the study, and 25 out of the 26 completed the program. Quantitative data collected from one student who withdrew in the middle of the program was excluded from the analysis, so data from 25 participants were included in the final quantitative analysis. Quantitative analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 software, and the reliability of the instruments, frequency, and descriptive statistics were analyzed. The differences in the scores before and after education were compared using paired t-test. The effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d due to the small sample size. The normality of the data was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and normal distributions of attitude toward older adults, knowledge of, awareness of, attitude towards, and intent to report elder abuse were checked.

The interview was conducted by the first author, who had experience in qualitative research. The researcher used a list of semi-structured questions and audio-recorded the interviews. Further, an assistant researcher observed participants’ reactions and took field notes as necessary. The interviews were transcribed, and the first author and another author independently performed content analysis to extract themes by category, theme clusters, and categorization.

Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics

Table 3 shows the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. The majority of participants were women (88.0%), and the mean age was 21.8 years, ranging from 20–28 years. Only 10 participants had prior education about elder abuse or exposure to an elder abuse awareness campaign before enrolling in the study. Regarding intervening in an elder abuse case, 12 participants stated that they would only report the incident before the education, while 4 stated that they would do so after the program. Moreover, before the education, 2 participants indicated that they would report the incident and intervene with only the older adult, while after the program, 10 stated that they would do the same.

Effects of the education program on intent to report elder abuse among nursing students

After the program, nursing students’ attitude toward older adults (Cohen’s d = 1.08), knowledge (Cohen’s d = 2.15), awareness (Cohen’s d = 1.56), attitude (Cohen’s d = 1.85), and intent to report elder abuse (Cohen’s d = 2.78) increased, confirming the positive effects of the program.

Table 4 shows the results before and after the education.

Attitude toward older adults significantly increased from 80.88 ± 11.39 at the baseline to 92.4 ± 9.84 after education (t = -6.38, p = 0.028, Cohen’s d = 1.08). Knowledge about elder abuse significantly increased from 4.76 ± 1.79 at the baseline to 8.84 ± 1.99 after education (t = -12.13, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.15). Awareness of elder abuse significantly increased from 45.16 ± 5.38 at the baseline to 52.32 ± 3.57 after education (t = -8.75, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.56). By domain, the scores for physical abuse (t = -5.25, p < 0.001), emotional abuse (t = -7.21, p < 0.001), financial abuse (t = -2.37, p = 0.026), and neglect (t = -4.13, p < 0.001) statistically significantly increased.

Attitude toward elder abuse significantly increased from 56.16 ± 3.90 at the baseline to 63.12 ± 3.61 after education (t = -7.41, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.85). By domain, the scores for attitude (t = -5.23, p < 0.001), subjective norms (t = -4.55, p < 0.001), and perceived behavioral control (t = -3.27, p = 0.003) statistically significantly increased.

Intent to report elder abuse significantly increased from 32.08 ± 1.73 at the baseline to 39.76 ± 3.50 after education (t = -9.21, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.08).

Participants’ feedback on education program for promoting nursing students’ intent to report elder abuse

Reason for participating in the program.

The reasons for participating in the program included self-improvement ( n = 2), increased perceived need for education after the informed consent process ( n = 1), exploring topics for course assignment ( n = 1), perceived need for education during practicum ( n = 5), perceived need for education while providing care for families of older adults ( n = 1), and had an interest in the topic ( n = 1). The participants were satisfied with the education program overall.

Benefits and challenges of the program

Learning about care for older adults.

Students mentioned learning about different types of elder abuse and laws pertaining to elder abuse as a benefit of participating in the program. Furthermore, they also stated that they can utilize what they have learned to provide more meaningful care for older adults.

Developing competencies as a nursing student (formal Para).

Most students stated that they liked the fact that the education program was free and that they participated to learn instead of just passing an exam. Unlike other education programs, they were allowed to relieve their skepticism about nursing by interacting with their fellow students proudly about nursing and engaging in introspection, based on which they were able to better recognize the value of nursing.

Feedback for improving the feasibility of the program

Need to emphasize that the program is about reporting elder abuse.

Many nursing students who saw the advertisement poster misunderstood the program as a geriatric nursing program when they were recruited. Thus, the students advised that we emphasize the program as an educational program for nursing students whose prospective mandates reporting elder abuse.

Development of an e-learning program

With in-person activities restricted during the COVID-19 pandemic, students suggested developing strategies that allow more nursing students to access the program. For example, they recommended converting the offline program to an e-learning program for promoting intent to report elder abuse.

This pilot study aimed to develop an educational program to promote intent to report elder abuse among nursing students and assess its effectiveness. Additionally, we aimed to collect feedback from participants to improve the feasibility of the program. After administering the developed education program about elder abuse, students showed improved attitudes toward older adults, knowledge of, awareness of, attitude towards, and intent to report elder abuse, confirming the positive effects of the program.

These results support the findings of a previous study that investigated awareness, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and attitude toward elder abuse among nursing students in Korea, where students who took a relevant course demonstrated a higher level of awareness, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [ 10 ]. Therefore, continuously providing a systematic education program on elder abuse reporting to nursing students, especially during a time witnessing various instances of elder abuse due to the burgeoning older adult population [ 21 ] and Korean nurses’ awareness of elder abuse being low compared to other occupational groups in Korea [ 9 ], will not only bolster nursing students’ competencies for responding to elder abuse incidents but will also contribute to addressing the crucial societal issue. However, it is necessary to update how the program is promoted and modify the current program, particularly in light of comments that various platforms of operation should be explored to facilitate the implementation and dissemination of the program. Therefore, we will discuss three factors that should be improved.

First, the title of the program should be chosen such that the contents of the program are clearly conveyed when advertising the program. The objective of the education program developed in this study was to educate nursing students about their duty to report elder abuse. However, some participants misunderstood the program as an educational program for geriatric nursing during the recruitment process. Further, none of the participants in the program demonstrated an interest in elder abuse reporting or an increased desire to improve their ability to report the same. Therefore, the title of the program should reflect nursing students’ opinions. Students’ opinions can be collected by asking them to choose from a list of a few titles. Further, considering that a contest enhances the credibility of a company and boosts individuals’ willingness to be involved in the said company [ 22 ], launching a naming contest for the program could attract students’ attention, deepen their understanding of the program, and increase the participation rate.

Second, the instructors need to use questions that trigger thinking to give students adequate opportunities to think about the topic (reporting elder abuse) on their own and discuss it among them. The students reported that they experienced a positive emotional process where they felt more value in nursing as they contemplated about a topic with fellow students and engaged in introspection and reflection. Nurses in geriatric hospitals in Korea experience ethical conflicts as “being distressed,” namely moral distress, which refers to being unable to do the right thing despite being aware of it [ 23 ]. One main cause of nurses’ distress is a working environment that does not fulfill ethical obligations [ 23 ]. In East Asian contexts, elder abuse is pervasively perceived as a personal family issue. Family matters and issues are kept within the family, as sharing them with outsiders can expose the family to public embarrassment and lead to loss of face. Besides, other reasons why older adults remain silent include a culture‐specific misunderstanding of elder abuse, shame, self‐blame, and the belief of inescapable ill fate [ 24 ].

Therefore, mandated reporters in Korea choose not to execute mandatory reporting because they feel that by modifying the conditions that cause abuse, family members can participate in providing care for older adults at home. They believe that providing care at home, improving the relationship between older adults and their families, and intermediation provides a better cultural option for older adults [ 25 ]. Additionally, older Korean adults, as victims, expressed reluctance to seek help or attention despite abuse experiences due to a culture of family honor and filial piety, an obligation to uphold norms, such as endurance and self-effacement, and belief in fatalism (acceptance of fate) [ 24 ]. To address this problem, education programs using verified teaching methods, such as the nudge strategy, and exemplary cases that arouse moral emotions advancing from the conventional moral education focused on character and virtue towards a cognitive approach should be actively developed [ 26 ].

Third, a non-face-to-face education program should be developed. We could not expect students’ active participation amid restrictions on in-person activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The students also suggested that a non-face-to-face education program should be developed. In a recent study, nurses and social workers who participated in virtual-reality-based elder abuse and neglect educational intervention acquired knowledge about identifying elder abuse and neglect and demonstrated 99% accuracy in their decisions for mandatory reporting. Further, the knowledge and skills they acquired in the intervention brought positive changes in their actual work performance [ 27 ]. These results suggest that a non-face-to-face education program can adequately alter knowledge and teaching skills that may have a positive impact in a clinical setting. Therefore, developing a non-face-to-face version of our program would provide effective education for a larger population of nursing students.

This pilot study aims to develop an educational program to promote the intent to report elder abuse among nursing students and assess its effectiveness. Despite the strength—developing and examining the effectiveness of an education program about elder abuse reporting based on nursing students’ educational needs—this study has a few limitations. First, some participants misunderstood this program as an education program for geriatric nursing instead of elder abuse. This misunderstanding could have contributed to the lower scores found on the pre-test. Thus, the educational goal should be clarified and promoted in the process of participant recruitment to confirm this program’s effectiveness in the follow-up study. Second, all participants were students at a single school. Additionally, students volunteered to participate in this offline program while all other courses were administered online, which indicates that only students with high educational needs may have been recruited. Thus, our findings cannot be generalized. Studies including nursing students from various regions and diverse demographic backgrounds are needed. In summary, future research should focus on planning preventive measures for elder abuse, developing suitable training programs, and supporting the older adult population. The method of program delivery should be improved and tailored strategies to boost program engagement among nursing students should be explored to implement and disseminate the program.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Yon Y, Ramiro-Gonzalez M, Mikton CR, Huber M, Sethi D. The prevalence of elder abuse in institutional settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(1):58–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky093 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lee YJ, Kim Y, Park JI. Prevalence and factors associated with elder abuse in community-dwelling elderly in Korea: Mediation effects of social support. Psychiatry Investig. 2021;18(11):1044. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2021.0156 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Han SD, Mosqueda L. Elder abuse in the COVID-19 era. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(7):1386–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16496 .

Ha J, Park D. Educational needs related to elder abuse among undergraduate nursing students in Korea: an importance-performance analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;104:104975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104975 .

MohdMydin FH, Othman S. Elder abuse and neglect intervention in the clinical setting: perceptions and barriers faced by primary care physicians in Malaysia. J Interpers Violence. 2020;35(23–24):6041–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517726411 .

Article Google Scholar

Miller CA. Nursing for wellness in older adults. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009; 162.

Ministry of Health and Welfare. Elder Abuse in Korea. 2019. https://www.korea.kr/archive/expDocView.do?docId=40008

Ministry of Health and Welfare. Guideline of integrated health promotion in communities. 2021. http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=0320&CONT_SEQ=364090 . Accessed 20 Mar 2023.

Park JH, Cho CM. Community nurses’ perceptions of elder abuse based on an ecological system model: a descriptive study. J Korean Gerontol Nurs. 2022;24(4):412–23. https://doi.org/10.17079/jkgn.2022.24.4.412 .

Lee YJ, Kim YS. A study on the influence of nursing students’ perception, subjective norms and perceived behavior control on attitudes toward elder abuse. J Korea Acad-Industr Cooperat Soc. 2018;19(5):410–7. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2018.19.5.410 .

Estabrook B, Zapka J, Lemon SC. Evaluating the implementation of a hospital work-site obesity prevention intervention: applying the RE-AIM framework. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(2):190–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839910385897 .

Wozniak L, Rees S, Soprovich A, Al Sayah F, Johnson ST, Majumdar SR, Johnson JA. Applying the RE-AIM framework to the Alberta’s caring for diabetes project: a protocol for a comprehensive evaluation of primary care quality improvement interventions. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5):e002099. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002099 .

Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Procto EK. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. 2nd ed. England: Oxford University Press in England, Inc; 2012.

Hil R. What sample size is “enough” in internet survey research? Interpersonal Computing and Technology. An Electronic Journal for the 21st Century. 1998;6(3–4):1–12.

Dick W, Carey L, Carey JO. The systematic design of instruction, 7th ed. United States: Allyn & Bacon in the United States. 2011.

Sanders GF, Montgomery JE, Pittman JF, Balkwell C. Youth’s attitudes toward the elderly. J Appl Gerontol. 1984;3(1):59–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/073346488400300107 .

Im YS. Knowledge and attitude toward the elderly of a general hospital nurses [Unpublished Master’s thesis, Chosun University]. 2002.

Google Scholar

Moon A, Williams O. Perceptions of elder abuse and help-seeking patterns among African-American, Caucasian American, and Korean-American elderly women. Gerontol. 1993;33(3):386–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/33.3.386 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Yoo SH, Kim CS. A study of old persons' subjective perceptions on elder abuse. In: Korean Institute of Gerontology: a study of the current state and a countermeasure on elder abuse. Korea: Korean Institute of Gerontology in Korea; 2004. p. 9–39.

Cho YK. Influencing factors on nurses’ intention of intervening in elder abuse [Master Thesis, Yonsei university]. 2014.

Kong J, Jeon H. Functional decline and emotional elder abuse: a population-based study of older Korean adults. J Fam Violence. 2018;33:17–26.

Kim YH. The study of the contest exhibition on corporate image and behavior intention. J Korea Content Assoc. 2017;17(12):590–9.

Kim M, Oh Y, Kong B. Ethical conflicts experienced by nurses in geriatric hospitals in South Korea: “if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4442.

Lee Y-S, Moon A, Gomez C. Elder mistreatment, culture, and help-seeking: a cross-cultural comparison of older Chinese and Korean immigrants. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2014;26:244–69.

Doe SS, Han HK, McCaslin R. Cultural and ethical issues in Korea’s recent elder abuse reporting system. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2009;21:170–85.

Engelen B, Thomas A, Archer A, Van de Ven N. Exemplars and nudges: Combining two strategies for moral education. J Moral Educ. 2018;47(3):346–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2017.1396966 .

Pickering CE, Ridenour K, Salaysay Z, Reyes-Gastelum D, Pierce SJ. EATI Island–a virtual-reality-based elder abuse and neglect educational intervention. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2018;39(4):445–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2016.1203310 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to sincerely thank the participants of this study.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A8046754). The funding source had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Nursing, Semyung University, 65 Semyung-Ro, Jechoen-Si, Chungbuk, Republic of Korea

Department of Nursing, Dong-A University, 3 Dongdaeshin-Dong Seogu, Busan, 602–714, Republic of Korea

Jeongmin Ha

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Ha contributed to the conception and design of the study, and discussion. Park contributed to the conception and design of the study, theoretical introduction and discussion, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. Ha and Park were a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jeongmin Ha .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Semyung University (IRB No SMU-2020–08-011). The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, voluntary participation, freedom to withdraw from the study, guarantee of anonymity, and use of collected data for only research purposes, and written informed consent was obtained after confirming that the participants have accurately understood the purpose, procedure, and method of the study using the talk-back method. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (e.g., Helsinki declaration).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Park, D., Ha, J. Education program promoting report of elder abuse by nursing students: a pilot study. BMC Geriatr 23 , 204 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03931-0

Download citation

Received : 15 December 2022

Accepted : 25 March 2023

Published : 31 March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03931-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- ADDIE model

- Elder abuse

- Education program

- Nursing students

BMC Geriatrics

ISSN: 1471-2318

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Protecting Our Seniors From Abuse & Neglect

Recent Elder Abuse in Nursing Homes: Case Studies

Elder abuse is far more common than many people would like to believe. What’s worse, recent reports confirm that nursing home abuse skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Help keep your loved ones safe by reading these recent case studies on elder abuse in nursing homes. Accepting that elder abuse is a real problem is the first step in preventing it.

Examples of Elder Abuse in Nursing Homes: A Nationwide Problem

Nursing home abuse happens when trust is violated through an act — or a failure to act — that harms an older person. It can include emotional, financial, physical, or sexual abuse as well as nursing home neglect.

Tragically, a 2020 report from the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that roughly 1 in 6 adults 60 years old and over were the victims of elder abuse in nursing homes and other community settings.

Even worse, the WHO warns that this already alarming figure is likely to be too low since only 1 in 24 cases of elder abuse is ever reported.

Recent case studies on elder abuse in nursing homes show that this is, unfortunately, a nationwide problem.

The most common forms of nursing home abuse are:

- Emotional abuse : when an older person is yelled at, threatened, or belittled

- Nursing home neglect : substandard care of a nursing home resident

- Physical abuse : any form of violence that leaves an older person significantly injured, including cases of wrongful death

- Sexual abuse : any sexual contact with an elder who cannot give their consent

Thankfully, help is available if you or a loved one suffered nursing home abuse or neglect. Get a free case review to see if you can access legal compensation right now.

Get a free legal case review if you or a loved one has suffered abuse or neglect.

Examples of Case Studies on Elder & Nursing Home Abuse

1. suspected nursing home abuse in massachusetts.

After hundreds of 911 calls were made about suspected nursing home abuse, a criminal investigation is underway against an assisted living facility in Watertown, Massachusetts.

Several of the heartbreaking reports include:

- After responding to a call about a faulty ventilator, firefighters found that none of the electrical outlets in a resident’s room were working

- An injured nursing home resident was on the floor asking for help, but when firefighters asked the staff member in charge about it, she just laughed

- Firefighters found staff performing CPR on a man who had already been dead for hours

Further, in a case of suspected physical abuse at the same nursing home, the daughter of a dementia patient found her mother’s face severely battered.

“It was horrific. She had a huge gash on her forehead and a lump the size of a golf ball, her whole face was bruised.” – Daughter of Massachusetts nursing home resident

These examples reveal a widespread pattern of abuse and neglect by staff, which will hopefully be corrected. No nursing home resident should ever have to endure these hardships.

2. Nursing Home Sexual Abuse in Minneapolis

A male caregiver at a Minneapolis care facility was sentenced to eight years in prison for the rape of a nursing home resident with Alzheimer’s disease.

“My final memories of my mother’s life now include watching her bang uncontrollably on her private parts for days after the rape, with tears rolling down her eyes, apparently trying to tell me what had been done to her, but unable to speak.” – Daughter of sexual abuse victim

A follow-up investigation by CNN revealed that the rapist had assaulted multiple other residents, including those who suffered from mental or physical handicaps, before he was finally caught.

3. Nursing Home Neglect in Iowa

A nursing home resident in Iowa died after extreme neglect related to dehydration . The emergency room doctor believes she died from a stroke after not receiving any type of fluid for at least four to five days. The nursing home was fined $77,463.

Examples of Elder Abuse in Nursing Homes During the Pandemic

While nursing home abuse and neglect were already a very serious issue, the ongoing coronavirus pandemic made things even worse.

According to Human Rights Watch, neglect and isolation may be responsible for causing severe damage to countless nursing homes residents during the COVID-19 crisis.

Recent nursing home abuse case studies revealed:

- A resident in her 80s who was healthy and pre-pandemic died shortly after visitation stopped due to suspected malnutrition

- In less than a year, a dementia patient living in a nursing home went from 106 pounds to 82 pounds before being discharged and dying several days later

- A dementia patient in her 70s lost 20 pounds during the pandemic and developed painful bedsores on her buttocks and toes

Why Does Elder Abuse Happen in Nursing Homes?