- Earth and Environment

- Literature and the Arts

- Philosophy and Religion

- Plants and Animals

- Science and Technology

- Social Sciences and the Law

- Sports and Everyday Life

- Additional References

- Social sciences

- News wires white papers and books

The Education Reform Movement

4: the education reform movement.

The public school system is a significant part of the American landscape, an institution that many people take for granted. It's difficult to imagine a time in history when education was a privilege, not a right, a time when only the children of the wealthy received an education. But in the United States as recently as the mid-1800s, the idea of free, publicly funded education for all children was considered extremely radical. Due to the efforts of nineteenth-century reformers such as Horace Mann (1796–1859), the public school system became a reality. Although the American public school system is far from perfect, and undergoes nearly continuous reform, it remains one of the great democratic institutions of the nation. It holds the promise of equal educational opportunity for all children.

The colonial era

During the early years of the American colonial era, the opportunity for education depended primarily on a family's income level and place of residence. Colonial governments did not require any sort of education, and schools existed only in communities where the residents or the local church established them. Some communities valued education more highly than others, offering even poor children the opportunity for some learning.

A thorough education, however, was the privilege of upper-class children, primarily boys, who were sent to private schools in preparation for a university education. Children in private schools were likely to focus on studying the Bible, Latin, English, and Greek. Although some schools only allowed boys to attend, others allowed girls as well. In some communities, boys attended school during the winter, leaving them free to work on family farms during the summer; girls attended school during the summer, allowing them to focus on indoor chores during the winter months.

In many communities, young children whose families could afford to pay modest sums attended "dame schools," which were run by women in their homes. The students in dame schools memorized Bible passages and learned basic reading, writing, and math skills. In areas that were sparsely populated, including much of the South , families that could afford to educate their children hired tutors to come to their homes. Some sent their children to one-room schoolhouses, where students of all ages learned together. On occasion, privileged children were sent away from home to live at boarding schools and receive a broad education.

Religious groups were instrumental in creating schools in the American colonies. For some children, Sunday school was the only type of education they received. Religion was a prominent subject in the teaching program of nearly every school. Puritan (English Protestant) leaders in colonial America advocated literacy so that all children could read the Bible and keep the devil at bay. Education was highly valued by the Quakers, a Protestant sect that promoted equality and tolerance. The Dutch Reformed Church , along with the Dutch West India Company , opened schools in Dutch communities such as New Amsterdam , which was later renamed New York . Even among the very poor, many children learned to read, tutored by their parents at home, so that they could study the Bible.

WORDS TO KNOW

Educational opportunities for African American and Native American children were extremely limited. Most schools did not allow white children to be taught together with American Indian and black children. In some communities, however, Quakers and other groups established schools open to all children, or schools specifically for nonwhite pupils. Many educators who sought to teach Native American and African American children did so because they wanted to convert them to Christianity.

In 1642 Massachusetts passed the first law requiring schooling for every child. The law dictated that every town establish a school. The type of school depended on the town's population and would be funded by the families in that community. In many towns, the citizens believed it was not the government's place to make such laws, and they opted to pay a fine rather than establish a school. The residents of the town of Dedham, Massachusetts, however, took their duty seriously. They set up a school in 1645 that was available for free to all children, making it one of the first public schools in the nation. The following year, in 1646, lawmakers in Virginia voted to set aside public money to establish schools. Such schools, however, were only available to white children.

Young students in the colonial years had minimal school supplies. They were often given hornbooks, which were paddle-shaped pieces of wood with a piece of paper attached. Printed on the paper was usually the alphabet and a religious verse, such as the Lord's Prayer. The paper was covered by a plastic-like transparent sheet made from an animal's horn. Students also learned with the aid of primers, or introductory reading books.

From the late 1600s through the 1700s, many colonial schoolchildren used The New England Primer in addition to the Bible. The primer contained lessons on spelling, reading, and religious verses. Students learned primarily by rote, memorizing the verses in their primer and reciting them back for the teacher. The teacher maintained strict discipline in the classroom, using physical punishments, like a rap on the wrist with a ruler, to keep students in line.

A new nation

As the borders of America expanded throughout the 1700s, the needs of its citizens also grew. More and more people felt that a child's education should go beyond religious instruction, reading, and writing. They thought school should include science, mathematics, and other practical subjects. Some citizens went so far as to suggest that Bible study and secular, or non-religious, education should be completely separate. They believed that churches' roles in education should be limited to Sunday school .

During the 1700s, a number of important universities and colleges were founded, including Yale, Princeton, and Columbia. American scholar and statesman Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) was instrumental in forming the University of Pennsylvania , which became the first American university that was established without a church affiliation and for the express purpose of secular higher education.

Many colonial communities also began to resist British influence on their schools, wishing to forge a unique American identity. Renowned man of letters Noah Webster (1758–1843) played a significant role in that arena, publishing a textbook in 1783 known as The Blue-back Speller . This book, widely used and hugely influential for more than a century, helped establish American English as distinct from British English. The Speller outlined different spellings and pronunciations for English words. For example, it suggested that "theatre" should be spelled "theater" and "plough" should be spelled "plow." Many years later, Webster published his American Dictionary of the English Language . A groundbreaking work, it served as the model for American dictionaries for many generations.

In the aftermath of the American Revolution (1775–83), leaders of the newly established United States promoted the idea of broad education for the nation's citizens, or at least for the white males. During this era, education for African Americans was regarded as unnecessary and, where slaves were concerned, dangerous. Most slave owners believed an education would only make slaves more inclined to rebel or escape. Thus, teaching slaves to read and write was outlawed in many southern states. Many felt the same way about educating girls, though some disagreed, noting that teaching girls was critical in building a strong democracy. Most girls would grow up to be mothers, and mothers were regarded as a great moral and intellectual influence on their children. If mothers were educated and enlightened, they would likely raise educated and democratically inclined children. This would help to strengthen the principles of the new republic.

Using the same argument, America's founding fathers, particularly President Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826; served 1801–09), contended that publicly funded education was a critical part of building and sustaining a democracy. Jefferson pointed out that it was a government's obligation, and in the government's best interest, to produce future generations of educated, enlightened potential leaders and voters. If the people could not read and write, then they could not vote. As a result, the democracy would collapse. Jefferson also explained that a public school system in which local communities maintained control was an excellent way for citizens to practice self-rule.

In 1778 Jefferson proposed to the Virginia Assembly a program offering three years of public school to all children (with the exception of black children). The outstanding male students would then have the opportunity to continue their schooling, eventually earning scholarships to universities. Citizens strongly resisted the idea of publicly funded education, objecting to the increased government involvement and the higher taxes necessary to pay for public schooling. Jefferson's proposal was rejected by the assembly. Jefferson submitted his proposal two more times during the next few decades and each time it failed to pass. Although his efforts did lead to the creation of the University of Virginia and laid the groundwork for future public school systems, Jefferson died several years before public education became a reality.

Growing pains in the early 1800s

The transition to independent nationhood and a new century did not immediately result in changes to the existing methods of educating children. Sophisticated schooling continued to be available only to children of the wealthy at private academies. In some communities, churches sponsored schools, paying part of students' tuition. Charity schools were funded by private donations, offering inexpensive or free education to lower-income families. Conditions in schools other than private academies were usually poor. Class sizes were very large and included students of all ages. Schools struggled to heat the building in winter and to keep the facilities clean. As in earlier generations, Sunday school was the only source of learning for many children. For others, education came in the form of an apprenticeship, a period of learning a particular trade, such as carpentry, from a master of that trade.

During the early decades of the 1800s, dramatic change was brewing in the United States due to the Industrial Revolution , which had started in England in the mid-1700s and had begun trickling into the United States by the late 1700s. The Industrial Revolution was characterized by numerous inventions and innovations that transformed American society from a loosely connected group of agrarian, or farming, states to an economically powerful nation based in urban manufacturing. Abundant factory jobs drew people to cities in the American Northeast, many from nearby family farms and others from European countries. As the cities grew, so did social ills such as poverty, crime, overcrowding, and disease. Searching for solutions to these problems, more and more citizens began calling for a public school system.

Among the most determined supporters of public schools were those most likely to benefit from them: members of the working class. In the absence of free education, the working classes saw a future where they were unable to improve their lives, stuck in low-income jobs and tenement housing while the wealthy few became richer and more powerful. As stated by Leonard Everett Fisher in his The Schools , "The result would be a virtual economic slavery that would undermine the course of political freedom envisioned by the Founding Fathers and in the end destroy the very meaning of a free America." For this reason, publicly funded education became one of the major issues of the early labor unions. Workers understood that a just society requires all children to be educated, not just those of the wealthy. As quoted on the Digital History Web site, a union organization known as the Philadelphia Workingmen's Committee declared in an 1830 document: "The original element of a despotism [a government possessing absolute power] is a monopoly of talent, which consigns [relegates] the multitude to comparative ignorance, and secures the balance of knowledge on the side of the rich and the rulers."

Working people understood that even free schools might not be accessible to the poorest working families, who needed their children's wages in order to survive. As a solution, some proposed manual labor schools that would combine wage-earning with study, allowing even children from desperately poor families to be educated. For families with children too young to work, a free school system would relieve them of the need to pay someone to care for their children while the parents worked.

Workers, and other citizens as well, argued that public education was an essential tool for competing in an increasingly industrialized world. A sophisticated and broad-based school system would produce a more highly skilled workforce. Better schooling would also lead to more inventions and innovations, critical to the continued growth of American manufacturing.

In addition to those in the working class, a number of middle-class citizens also supported the notion of public education. Some advocated universal schooling, or free education for all children, out of a moral obligation to improve others' lives. Many considered it a necessity for imposing control on a rapidly changing nation. With the explosive population growth in cities, ever-increasing numbers of young people spent their days wandering the streets, looking for ways to fill their time. Public schools would get children off the streets, instilling obedience and discipline. In addition, schools were seen as a valuable tool for deali0ng with the numerous immigrants moving to

Massachusetts: Educational Pioneer

Massachusetts played a critical role in early American history and in many respects led the way in the development of a public school system.

During the early colonial era, Massachusetts was the center of cultural and intellectual activity in the New World. The city of Boston was home to the nation's first secondary school , a private academy known as Boston Latin, which was established by Puritans in 1635. The following year, Harvard College was founded, the first institute of higher education in the colonies. The first class consisted of nine students. In its earliest years, Harvard's mission was to educate graduates of Boston Latin for the ministry. In 1639 the Mather School was founded in Dorchester, becoming the first free American school. In 1642 Massachusetts passed the first law in the colonies mandating that all children be educated. The government gave no indication of how such a task would be accomplished. It only indicated that it was the duty of each town to establish some type of school to be paid for by the families in that community.

Just as it had been during the colonial era, Massachusetts was an education pioneer of the nineteenth century. In 1821 the city of Boston opened the English Classical School (later known as the English School), the nation's first public high school. Unlike the public schools of the modern era, the English School charged tuition. What made it different from the private academies of that era was that some of its funding came from the government. A few years later, in 1827, Massachusetts passed a law stating that all towns with five hundred or more families had to establish at least two high schools, one for girls and one for boys. In 1837 Mary Lyon (1797–1849) founded Mount Holyoke Seminary, which was not actually a seminary but in fact the first non-religious institute of higher learning created just for women. Forty years later, Helen Magill White (1853–1944), having studied at Boston University, became the first woman in American history to earn a Ph.D.

Much of Massachusetts' prominence as a leader in school reform is due to Horace Mann , the champion of the common, or public, school in the mid-1800s. Mann was a Massachusetts state legislator before becoming the secretary of the state's first board of education in 1837. As part of his campaign to establish quality education for all children, Mann played a key role in the founding of the nation's first teacher training institute, which opened in Lexington in 1839. More than a decade later, in 1852, thanks to Mann's tireless lobbying, Massachusetts became the first state to require every child to get an education. In 1855, the state again became a leader for the nation as the first state to admit all students to public schools, regardless of religion, race, or ethnicity.

American cities. Enrollment in public school would help immigrants assimilate, or blend into American culture, by teaching them American values and practices.

Some Americans, particularly business owners and other elite members of the upper classes, strongly opposed the idea of a public school system. One reason for this opposition was fear that they would bear an undue burden in the tax-based funding of schools. In addition, they worried that educating the working classes would, in the future, deprive owners of their needed workers. They felt that once all citizens had the opportunity of education, few would choose to perform manual labor. If large numbers from the working classes could rise to the middle class, the social structure on which the wealthy elites had built their fortunes would collapse. Many religious leaders also objected to the establishment of a public school system. They were concerned that such schools would not teach religious doctrine and would reduce the importance of religion in citizens' lives.

Horace Mann and the common-school era

Beginning in the late 1830s, Massachusetts reformer Horace Mann led the charge for the nation's first statewide public-school system. As a member of the Massachusetts state legislature, Mann fought for the separation of church and state . He also worked to make many changes to his state's criminal justice system. He fought for the separation of the mentally ill from general prison populations, abolished the practice of public hangings, and established more appropriate punishments for petty crimes, many of which had formerly been punished by hanging. Mann also addressed the issue of public education, embarking on a lifelong quest to establish free, mandatory schooling for American children. He convinced the Massachusetts legislature to establish a board of education for the purpose of building a statewide school system, the nation's first. In 1837 Mann became the first secretary of Massachusetts' newly formed board of education.

As the head of the board of education, Mann traveled throughout Massachusetts, inspecting schools and persuading the citizens to support public education. Over the course of six years, Mann inspected hundreds of schools. However, his findings troubled him. Many of the schools were in terrible condition, with inadequate lighting and heating, structural problems, and minimal textbooks and other supplies for the students. During his travels, Mann held town meetings to discuss the terrible state of the existing schools and to propose the establishment of a statewide network of free public schools, which he referred to as common schools.

Mann's vision for common schools involved high-quality education with professionally trained teachers. School would be mandatory and free for all children, funded completely by tax dollars. The state board of education would impose standards that all schools in the state would follow, including the use of standardized textbooks. Mann went so far as to outline details of school life such as the use of bells and blackboards, the practice of dividing children by age and ability, and the tradition of midmorning recess for younger students.

Mann encountered strong opposition wherever he went. People resented the idea of the government getting involved in local matters, and they objected intensely to paying higher taxes. Particularly offensive was the notion that even the people who did not have children would have to pay taxes to educate the children of others. Factory owners also protested the loss of child workers, the cheapest segment of their workforce. Parents worried about meeting expenses without their older children's income. Mann ultimately persuaded people that quality education was necessary not only for the welfare of the children but for the survival of democracy in the United States.

Having won the support of the people, Mann went on to victory in the legislature, which dedicated a large sum of money to building a statewide school system. By the early 1850s, the Massachusetts legislature passed a law requiring all children to attend school and also mandated that the school year be at least six months long, the first such laws in the nation. A significant part of Mann's proposal involved teacher training. He obtained funding from the Massachusetts legislature to create the country's first teacher training college, built in Lexington in 1839. Mann's influence extended far beyond Massachusetts. His reports on school reform were widely read in the United States and in other nations as well. He traveled throughout the Northeast to lobby for common schools in those states. His efforts led directly to statewide school systems throughout the region, and his tireless efforts laid the groundwork for the entire nation's public school systems.

Discrimination in common schools

Although common schools were to provide a quality education to all children, the reality was that many children were excluded. In the northeastern United States, the number of European immigrants continued to grow. Many from Ireland were Catholic, and they encountered resentment and discrimination from the largely Protestant populations of American cities. Such discrimination was readily apparent in schools and became a particular source of tension in the New York City schools. Education reformers spoke of common schools as nonsectarian, or not favoring one religion or denomination over another. But in practice, New York public schools used the Protestant version of the Bible and Protestant hymn books. In addition, many textbooks contained anti-Irish and anti-Catholic references. In School: The Story of American Public Education, historian Carl Kaestle recalled one such offensive reference. It read: "The Irish immigration has emptied out the common sewers of Ireland into our waters." Many teachers encouraged anti-Catholic stereotypes, suggesting that Catholicism was in opposition to democratic values.

In response to such teachings, many Catholic parents in New York prevented their children from attending public schools. Catholic religious and community leaders voiced objections to paying taxes for schools where their children faced discrimination. They demanded that the government designate tax dollars for the construction of Catholic schools. Opponents feared that this demand would soon be echoed by Jewish leaders and by other Christian denominations, resulting in a greatly diminished school fund.

Thus began a debate in New York City about government funding of religious schools that has continued throughout the nation into the twenty-first century. Rather than award each religion its own share of public funding, New York officials made an effort to eliminate anti-Catholic bias in public schools. As a result, more Catholics did enroll in public schools. At the same time, however, the Catholic Church began establishing an extensive system of parochial schools, which are privately funded religious schools. An 1841 New York law officially prohibited all religious teaching in public schools, but the law was widely ignored in classrooms.

In addition to discrimination against Irish immigrants, many non-English-speaking immigrants were treated unfairly or excluded from public schools. Girls also faced discrimination. Many people considered it unnecessary to educate girls. The children most routinely and systematically denied educational opportunities, however, were African Americans . In the South , most black children were slaves, and very few were allowed to learn basic skills like reading and writing. Attending school was not an option. In the free states, black children were either prevented from attending public schools or, in cities like Boston and New York, were sent to all-black schools that were highly inferior to the white schools.

Some black citizens felt that their best option was to improve the quality of black schools. However, most believed that segregation (the separation of the races) was wrong, and that they had to fight for their children to be allowed to enroll in the all-white public schools. In the mid-1840s, one African American parent began a fight with the Boston school district. He wanted his daughter to be able to attend an all-white school near their home rather than travel a great distance to an all-black school. Benjamin Roberts sued the City of Boston and lost, then pleaded his case to the Massachusetts legislature. In 1855 Massachusetts became the first state in the nation to pass a law prohibiting segregation in schools.

Reconstruction and westward expansion

Problems faced by the growing network of public schools soon faded into the background as the nation split in two over the issues of slavery and states' rights. Tensions between the North and South escalated throughout the mid-1800s, culminating in the American Civil War (1861–65). After the war, the federal government began a program known as Reconstruction, designed to rebuild the South and unify the war-torn nation. With the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865, slavery was abolished throughout the United States. Constitutional amendments and civil rights acts followed which further expanded the legal rights of African Americans. They were granted citizenship, equal protection under the law, and the right to vote, among other rights.

For a brief period, until the Reconstruction Era (1865–77) ended, African Americans were able to exercise some rights in American society. Finally being able to receive an education was among their most treasured goals. For most southern blacks, the post- Civil War period was their first opportunity to attend any kind of school. The Freedman's Bureau, an agency designed to help former slaves find jobs and homes after emancipation, or freedom from slavery, built numerous schools for African American children during Reconstruction. Once Reconstruction had ended, and the federal government no longer had any control in the South, most southern states dramatically cut their education budgets, with black schools hit the hardest. For the next several generations, southern schools were the poorest in the nation, with black schools being deprived the most.

Elsewhere in the nation, public schools experienced tremendous growth in the last decades of the 1800s. While many citizens continued to oppose the practice of taxing all citizens' property to pay for some citizens' children to go to school, more and more cities successfully established public school systems. For many newly established states in the West, education was seen as a critical way to build communities and attract settlers. Government officials saw public schools as an effective way to tame the Wild West , teaching pioneer children proper American values and behavior.

A series of books known as the McGuffey readers played a significant role in that campaign. Used by millions of schoolchildren during the 1800s, the McGuffey readers served as standardized textbooks teaching children how to read, write, and spell. Those textbooks intended for older students also contained instruction in history, science, and philosophy. Equally important to parents and teachers, the McGuffey readers, named for their authors, William Holmes McGuffey (1800–1873) and his brother Alexander (1816–1896), taught religious, patriotic, and moral values. The McGuffey readers, through their teachings about the importance of hard work and the divine blessings of the United States, are credited with spreading the American value system to the entire nation.

To meet the rapidly growing demand, schools in the western states were established quickly, in whatever space was available. Numerous women, trained as teachers in the Northeast, made the long journey west to teach pioneer children. Thanks to the efforts of women's rights advocate Catharine Beecher (1800–1878), teaching had become a respected and popular profession for women. As such, many women felt it was their duty to travel far from home to bring enlightenment to the frontier. The conditions of most of the pioneer schools were shocking to the newly arrived teachers, with some schools little more

Catharine Beecher

Catharine Beecher, a member of a prominent family in nineteenth-century New England , devoted her life to expanding women's rights. She particularly promoted the right of girls to receive a broad education and the right of women to deliver that education as teachers. Beecher's outlook was not radical. She advocated an education for women so that they could excel in their traditional role as wives and mothers, not so they could break free of the barriers that society placed on them. She believed women would be excellent teachers because of their nurturing skills and their ability to serve as moral guides.

Beecher was born in New York in 1800, the eldest of nine children born to Lyman and Roxana Beecher. Lyman Beecher was a well-known and influential minister. Catharine's sister Harriet, writing as Harriet Beecher Stowe , later became famous as the author of Uncle Tom 's Cabin , a novel depicting the horrors and humiliation of slavery. The Beecher family moved to Litchfield, Connecticut, in 1809. Catharine Beecher entered a private school for girls, learning about manners and morals as well as painting and music. At the age of sixteen, Beecher had to leave the school when her mother died. She spent the next few years helping to care for her siblings and run the family home.

At the age of eighteen Beecher took a job as a teacher at a private girls' school in New London, Connecticut. In 1824 she opened her own school in Hartford called the Hartford Female Seminary. She rapidly gained a reputation for providing young women with a quality education, a rare experience in that era. Her students studied the usual female topics of morals and religion, but Beecher also featured courses in algebra, chemistry, physics, history, Latin, and other subjects. When her father moved to Cincinnati in 1832, Beecher went with him, opening another school there, the Western Female Institute.

Around that time Beecher had begun a quest to educate women for the teaching profession. She believed it was an appropriate job for respectable women. She also felt women could play an important role in the nation's growth by educating children in the expanding western territories. At her Western Female Institute, Beecher trained women to become teachers, hoping to inspire the founding of numerous teacher training schools.

Beecher's mission to civilize the Wild West and protect the nation from ignorance began to gain widespread support. Her Central Committee for Promoting National Education trained hundreds of women as teachers and sent them west to educate pioneer children. Beecher became a well-known figure, and her fame increased dramatically with the 1841 publication of her book A Treatise on Domestic Economy for the Use of Young Ladies at Home and at School . In this work, Beecher gave practical advice on running a household while also praising the importance of so-called women's work. Her book was extremely popular and only served to increase her influence on American society. Many historians credit Beecher with opening the profession of teaching to women. During her lifetime she brought about a shift in the nation's perceptions, making teaching a respectable option for women.

than shacks hastily built on the prairie. Western society was rougher and less civilized than that of the Northeast, and many of the adults were barely able to read and write. The emergence of women teachers during that era, in the West and elsewhere, changed the tone in American classrooms. As historian Kathryn Kish Sklar stated in School , women teachers "created a new ethic in schools … in which the teacher cared for the students."

Reforms of the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era, which roughly covers the first three decades of the 1900s, was a period of widespread social activism. The United States had been growing at a rapid rate, both in terms of population increases due to massive numbers of immigrants and in terms of industrial expansion. Reformers, also known as progressives, tackled numerous aspects of society, hoping to improve living and working conditions for all Americans. Some addressed women's rights, others fought against government corruption. Still others sought to improve working conditions in plants and factories. Many progressives devoted their time to helping the poor, while others dedicated themselves to outlawing alcohol. A significant number of reformers addressed the educational system. They used varying approaches and applied different methods, but all sought alternatives to traditional schooling.

One of the goals of reformers was to make sure every child could go to school. A significant number of children in the early twentieth century went to the factory to work each day rather than going to school. Progressives sought to end the practice of child labor and make attendance at school mandatory. Reformers also placed high importance on dealing with the massive influx of immigrants. In the forty years between 1890 and 1930, more than twenty million immigrants from dozens of different countries came to the United States. Most were poor and many could not speak English. The public school system faced a tremendous challenge in trying to educate such a diverse population. In spite of such challenges, the goal for the American school system was a lofty one. Schools were seen as the most effective way to help immigrant children assimilate, learning not just the English language but the American way of life.

During the 1870s, American educator Francis W. Parker (1837–1902), having spent three years in Europe studying educational theory, introduced a radical new method of teaching to the school system in Quincy, Illinois. Most classrooms at that time were run in a strict, authoritarian fashion, with students learning all subjects by memorizing passages of books and reciting them back. Parker brought an alternative approach that led directly to the progressive education movement of the early 1900s and permanently altered the state of American education. Basing his theories on those he learned in Europe, Parker introduced a style of teaching that relied less on discipline and more on creativity, free expression, and learning through experience.

Known as the Quincy Movement, these methods promoted child-centered education, theorizing that children would learn better if lessons incorporated their experience and interests. Parker's approach met with immediate success. The students thrived and Parker was asked to take the Quincy Movement to the public schools of Boston. Parker also played a significant role in training teachers in his methods. He opened a teacher training school in Chicago that, in 1901, became the School of Education at the University of Chicago .

While Parker laid the foundation for progressive education , renowned educator John Dewey (1859–1952) expanded on Parker's theories and spread them throughout the country. Dewey established the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago in 1896 as a way to implement his theories, many of which echoed those of Parker. Dewey emphasized the notion of school as a means to teach children to be good democratic citizens. He noted that lessons should be tailored to best meet the needs and appeal to the curiosity and interests of each individual. Promoting a hands-on, interactive approach over conventional teaching methods, Dewey believed that going to school should involve far more than sitting at a desk and reciting memorized lessons.

In addition to teaching children the educational basics, Dewey advocated physical exercise and field trips outside the classroom. Many people misinterpreted Dewey's program, believing that he was suggesting a lax, undisciplined environment. But while Dewey rejected the strict control and physical punishments of earlier generations of teachers, he did not support the idea of an uncontrolled classroom. Rather, he believed teachers should closely supervise students, giving them guidance and encouragement.

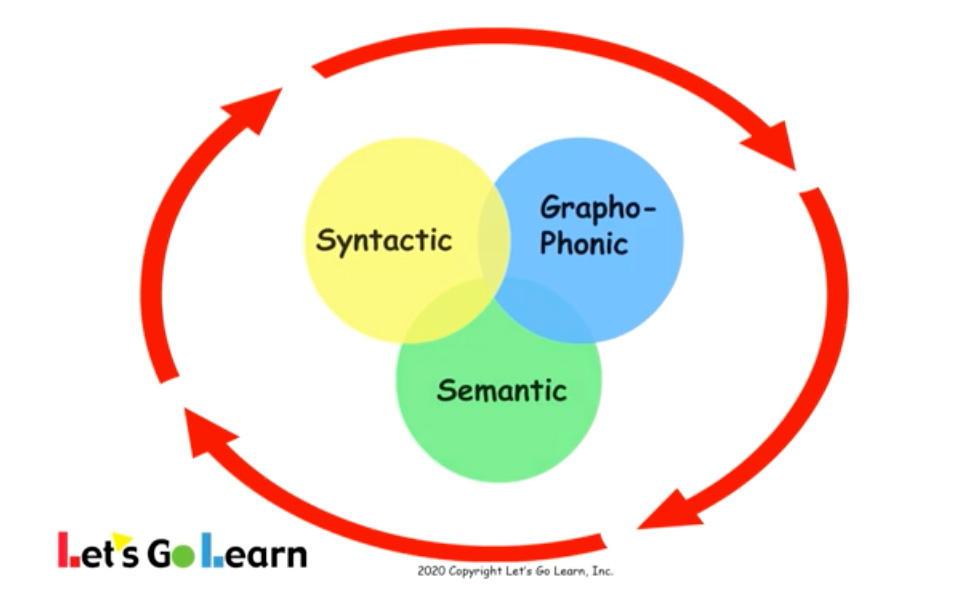

Another facet of Progressive Era education reforms had less to do with child-centered teaching and more to do with school administration. This group of reformers sought to make school systems more efficient. They centralized school administration and brought in experts to run schools. A new generation of administrators had been trained to take a scientific approach to managing schools. A commonly held belief among such administrators was that children should be evaluated early on and placed on an educational path appropriate to their intellectual abilities. Those children who performed well in school early on were placed on a scholarly track, headed for high school and college. Those who performed poorly in academics were given what was called vocational education . Such students were placed on an industrial track, taking courses that would teach them a trade or vocation.

To help them determine which track each student should take, administrators turned to a new type of analysis known as "intelligence quotient (IQ)" tests. These tests were developed during World War I (1914–18) to determine which soldiers qualified as officers. After the war, psychologists specializing in education convinced school administrators that the IQ tests would effectively determine the path each child should take in school. Rather than measuring what the children had learned, experts claimed IQ tests measured a child's natural intelligence. These tests were promoted as the most accurate, efficient, scientific way to determine children's needs and set their course for the future.

Critics warned against relying on IQ tests. They suggested that such tests were slanted in favor of children who had received more opportunities in life. For example, a child whose parents spoke English, were well educated, and had been actively involved in their children's education would score far better than a child whose parents did not speak English and had to work long hours at their jobs. For such reasons, children from low-income minority families generally scored lower on IQ tests. A low IQ score could restrict a child's opportunities for the rest of his or her life. Many educators believed that such tests were another way for society to discriminate against ethnic and racial minorities.

Protests about intelligence testing, however, were largely ignored. Soon, the tests became a regular part of the American education system. IQ tests served as the model for another widely administered exam: the Scholastic Aptitude Test, or SAT. Later known as the Scholastic Assessment Test, the SAT was developed in the 1940s as a screening device for college admissions. The test is still in widespread use today.

Mid-century changes

During the middle of the twentieth century, American schools underwent dramatic changes, many of which stemmed from new laws offering unprecedented educational opportunities. One of the most significant of such laws was the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the GI Bill of Rights or, simply, the GI Bill . "GI," which means "government issue," is a term commonly used to refer to any member of the American armed forces. The GI Bill offered all military personnel who had served during World War II (1939–45) federal funds to pay for college tuition, books, and even some living expenses during college.

Numerous veterans took advantage of the GI Bill. Many came from poor families and would not have been able to receive a higher education otherwise. The nation saw these veterans succeed in college, graduate, and secure high-paying jobs. At that point, the notion of college as something reserved for the elite members of society changed. More and more people began to see a college education not only as an attainable goal, but as the necessary path to career success. The GI Bill was eventually expanded to cover all members of the military, whether or not they had served during wartime.

After World War II , the United States became deeply involved in the Cold War (1945–91) with the Soviet Union . It was a conflict marked not by physical battles but by intense political tension and a fierce nuclear arms race. Fear of nuclear warfare and domination by the Communist Soviet Union guided American culture and policy during this era. The education system did not escape this influence. Many people began to feel that U.S. schools needed to improve their academic program in order to compete with Soviet-educated children.

In addition, some educators and citizens had come to believe that progressive education had gone too far, and that American schools had strayed from an emphasis on core subjects. Such critics felt that students needed to spend more time studying math and science and developing critical thinking skills and less time on art, home economics , and hygiene. A 1958 law designated $100 million of federal funds to be spent to improve schools, with a focus on developing more advanced math and science classes to better prepare students for global competition.

Over the course of a few decades, high school attendance had increased dramatically. By mid-century, vast numbers of American students were graduating from high school. According to the Digest of Education Statistics, 2004 , only 6.4 percent of seventeen-year-olds in the 1899–1900 school year had graduated from high school. That number jumped to 59 percent by 1949–1950. The number would rise even higher, reaching 77.1 percent in 1968–1969.

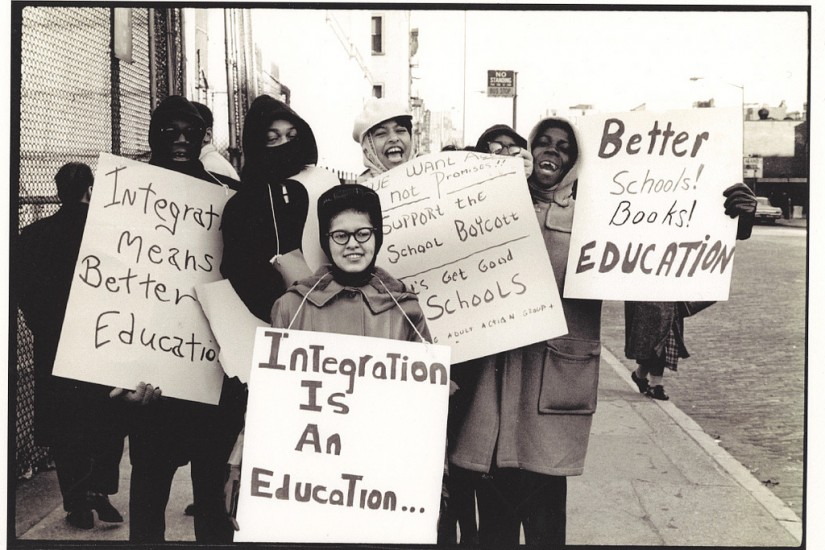

But while many American children enjoyed expanded educational opportunities, others were being held back by systematic, institutional racism. In the southern states, segregation laws prevented African American children from attending school with white children. Black students were forced to attend all-black schools, most of which were far inferior to white schools in terms of the conditions of the facilities, the available supplies, and the courses offered. With the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas in 1954, school segregation was declared illegal. Although the Brown decision marked a giant step forward, the battle for truly equal opportunity continued for many decades and had yet to be won at the start of the twenty-first century.

Much of the progress made toward the goal of educational opportunity during the 1960s and beyond was the result of laws passed during the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson (1908–1973; served 1963–69). Becoming president following the assassination of John F. Kennedy (1917–1963; served 1961–63), Johnson brought about the passage of a wide-ranging civil rights law initiated by Kennedy. Called the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , it allowed for legal fights to be waged against schools that failed to integrate. It also denied federal funds to any institution that practiced racial discrimination. This law forced reluctant school administrators to end discriminatory practices and to offer educational opportunity to all Americans.

Johnson also began a far-reaching program to aid the poor, known as the War on Poverty . He worked to gain passage of several economic bills that had a major impact on education. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 created several programs to bring educational opportunities to the disadvantaged. One of the best known and most successful of these programs was Head Start , a federally funded program to offer poor children the advantage of a preschool education . Studies showed that underprivileged children who did not attend preschool before kindergarten lagged behind their more advantaged classmates. Such students did not catch up even with tutoring and other assistance. Experts believed that early intellectual stimulation—such as being read to, playing games, singing songs, and taking field trips—was a critical factor in a child's development. The Head Start program was hugely successful from the beginning and continues to enroll millions of children.

Two 1965 laws further aided the disadvantaged in the quest for an education. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act set aside federal funds for school districts in poverty-stricken areas. The Higher Education Act created a program that offered grants and low-interest loans to help low-income students pay for college tuition. The law also took several steps to improve the quality of teaching, including establishing the National Teacher Corps to train educators working in low-income districts. The Higher Education Act made it possible for millions of low-income young people to attend college. It also benefited colleges by increasing enrollment. In addition, any school that accepted students who had received federal grants or loans was forced to comply with federal anti-discrimination laws. Eager for a larger student body, many colleges accepted federal loan recipients and ended admission policies that discriminated against racial and ethnic minorities and women.

Expanding students' rights

The gains made for African Americans during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s inspired other minority groups to organize and protest unfair treatment in areas like the workplace and the schools. Hispanic American students, particularly newcomers to the country who spoke primarily Spanish, experienced widespread discrimination. In many schools, Hispanic students were forbidden to speak Spanish. Even in communities where the vast majority of students were Hispanic, the curriculum offered no information about Hispanic culture and history. Many teachers in such schools sent clear messages to the Hispanic students that little was expected of them academically and that they should give up any hope of going to college.

During the late 1960s, Hispanic American students began to rebel, fed up with being discriminated against by white teachers and white school boards. In numerous schools, the Hispanic students presented a list of demands, including the hiring of some Hispanic teachers, the addition of courses and textbooks that included Hispanic history, and an overall improvement in the selection of courses and the treatment of Hispanic students. In many districts, Hispanic students went on strike, refusing to go to school and conducting protest marches. Such activism helped reshape a number of school districts, opening up opportunities for Hispanic students.

One of the more controversial changes from that period arose from the Bilingual Education Act, part of President Johnson's War on Poverty . Bilingual education meant that some schools would offer courses taught in a language other than English, gradually teaching enough English so that students could take all their classes in that language. The program has been controversial since its beginning, with some critics suggesting that it hurts non-English-speaking students by allowing them to spend years in American public schools without learning English. Advocates of the program say it is invaluable for new immigrants to be able to learn in their native language. They contend that it helps them academically and it shows respect for their culture and ethnicity.

From the beginning of the nation's history, girls had been discriminated against in schools. As late as the 1970s, institutional discrimination against girls was extremely common and extended from elementary school through the university level and beyond. Textbooks for young children routinely showed starkly different images of boys and girls, as pointed out by Leslie Wolfe in School: "Boys were strong, boys were masters, boys were active. Girls were sweet, girls were passive, girls watched, girls helped." In the older grades, girls were discouraged from pursuing advanced classes in math or science and from participating in sports. Girls' athletics programs at junior high and high schools were minimal or nonexistent. Colleges and professional schools, such as law or medical school, could legally reject applicants based on gender. According to School , in 1970 less than 1 percent of medical and law degrees were awarded to women, and only 1 percent of high school athletes were girls.

In 1972 the U.S. Congress passed a law that made such discrimination illegal. In that year, a series of amendments to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 included one known as Title IX. With the passage of Title IX, schools at all levels that received funding from the federal government were forbidden from excluding or otherwise discriminating against any student based on his or her sex. Athletic programs at all schools, including colleges and universities , must provide equal opportunities to female athletes and equal access to sports facilities. Colleges and professional schools receiving federal funding cannot bar students because of gender, a policy that protects men as well as women. Textbooks that used gender stereotypes or showed gender bias had to be removed from classrooms.

It has taken numerous lawsuits and many years to achieve enforcement of Title IX, and the battle continues today. But such efforts have yielded dramatic changes in educational opportunities for girls. According to the Title IX Web site, the number of girls participating in high school athletics jumped from just under 300,000 in 1971 to 1972 to nearly three million in 2000 to 2001. The gains in college athletics have been more modest but are still significant. By the end of the twentieth century the number of women earning undergraduate degrees had risen to become roughly equal to that of men. Women still lagged behind men in earning professional degrees, though far more women received such degrees at the century's end than they had thirty years earlier.

Disabled students

Students with disabilities also derived enormous benefit from civil rights legislation in the 1970s. A 1975 law known as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which has since been renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), ordered schools to provide opportunities to mentally and physically disabled students. Prior to the passage of that law, most disabled students either received no education or were sent to residential facilities, many of which were in poor condition. The 1975 law gave disabled children the right to attend public schools and receive special education, a process known as "main-streaming." The government began providing schools with funding to pay for this program, which included transportation to and from school and structural changes to make schools accessible to those with physical disabilities.

The practice of mainstreaming has been controversial. Critics object to the inclusion of severely disabled students, citing high costs and the inability of teachers to give sufficient attention to nondisabled students. Overall, however, the 1975 law formed the basis for significant improvements in the treatment of the disabled in the United States.

A late-century wave of reform

When the U.S. economy took a downward turn during the 1970s, many government officials and business leaders blamed the nation's schools. They believed that standards were too low and that too many students graduated from high school ill-equipped to contribute to the nation's economic growth. In 1983 a panel of experts convened by the U.S. Department of Education delivered a report called "A Nation at Risk." The report, with its strongly worded condemnation of the American public school system, came as a shock to many people. It stated that the educational system was in the midst of a crisis and that the welfare of the nation would be in jeopardy if dramatic reforms were not implemented.

According to the report: "It is important, of course, to recognize that the average citizen today is better educated and more knowledgeable than the average citizen of a generation ago—more literate, and exposed to more mathematics, literature, and science. The positive impact of this fact on the well-being of our country and the lives of our people cannot be overstated. Nevertheless, the average graduate of our schools and colleges today is not as well-educated as the average graduate of 25 or 35 years ago, when a much smaller proportion of our population completed high school and college. The negative impact of this fact likewise cannot be overstated." The report writers added that "education should be at the top of the Nation's agenda."

Many educational experts, while acknowledging that public schools needed some reform, claimed that "A Nation at Risk" grossly overstated the problem. Such experts noted that, rather than experiencing a sharp decline, American schools had been steadily improving. Nonetheless, the report caught the attention of the American public and had the vigorous support of President Ronald Reagan (1911–2004; served 1981–89). A wave of new school reforms began.

Reformers suggested such changes as lengthening the school day and the school year, raising the standards that students had to meet in order to graduate, assigning more homework, and improving and increasing standardized tests. Ten years after these reforms had been implemented, educators found that academic achievement had improved only minimally. Some said the reforms were ineffective, while others suggested that the reforms were working but other factors combined to bring down the overall level of achievement. Such factors included a rise in the number of poor students during that same ten-year period and the underfunding and overcrowding of schools in poor, usually urban, districts.

School choice

During the 1980s, a new approach to fixing the problems of inner-city schools took shape. Many reformers believed that the principles behind a free-market economy could be applied to public school systems: consumers would have the ability to choose the school their children attended, and schools would have to compete with each other to win new students. Supporters of this practice, known as school choice, asserted that poorly performing schools would suffer a drop in enrollment, forcing them to either improve or shut down.

School choice, implemented in many school districts across the nation, has sparked heated debate. Supporters believe that competition is healthy for schools and will ultimately benefit all students. Critics state that school choice can be exercised primarily by white, middle-class families. Disadvantaged families are less able to take advantage of school choice. Therefore the poorest students stay at underperforming schools that have been abandoned by more privileged students. Drops in enrollment mean decreases in government funding. Thus, with a loss of funding, inner-city schools cannot afford to make the necessary improvements.

Some school-choice programs have resulted in noticeable improvements in educational quality. An experiment begun in East Harlem in 1974 resulted in numerous smaller, alternative high schools that achieved significant academic success. The more traditional schools in the district began to improve in order to compete, and the standards of the entire district were lifted. One reason for the success in East Harlem, however, was extra federal funding designed to encourage innovation. Where such funding was unavailable, school choice programs proved less successful. For example, in Minnesota, the first state to offer statewide school choice, the program resulted in little or no improvement in the quality of education and the performance of the students.

The most controversial aspect of school choice has been the movement to offer vouchers for use at private schools. The government gives a fixed dollar amount to a public school for each student attending that school in a given academic year. Many parents have argued that they should be able to use that money to pay for private-school tuition. In 1990, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, became the first city to offer school vouchers . Those who wished to participate in the program received funds that could be applied to the tuition of a nonreligious private school. Opponents expressed concern that a voucher program would drain much-needed funds from public schools, but advocates argued that such a program would, like other school choice programs, force public schools to improve in order to remain competitive. Another criticism of voucher programs concerns the difficulty in determining the quality of education received at private schools, which are not subject to the same oversight as public schools.

In some areas of the country, voucher proponents have pushed to include private religious schools in voucher programs. This proposal has aroused vigorous opposition, with critics asserting that it amounts to the government and taxpayers financially supporting religious institutions, which is a violation of the U.S. Constitution's requirement to keep church and state separate. In spite of strong opposition, some school districts, notably in Cleveland, Ohio, and in Milwaukee, have gone forward with voucher programs for all types of private schools.

Charter schools

Another controversial school reform that arose during the 1990s was the establishment of a new type of public school known as the charter school. Charter schools are free and open to all students. They receive per-pupil government funding comparable to a conventional public school. However, charter schools are run not by school boards but by groups of parents or teachers, by organizations, or, in some cases, by private companies. Any group that secures the approval of local or state school officials can open a charter school. That school must then demonstrate within a certain period of time that it has met its goals for academic achievement.

Often, charter schools focus on a particular program or a specific group of students. For example, some charter schools focus on the performing arts, science, or mathematics. Others serve at-risk students who have not functioned well in regular public schools. The first charter school was opened in Minnesota in 1991. In 1997 the U.S. Congress allocated $80 million for the construction of new charter schools. Within seven years, there were more than 3,000 charter schools throughout the nation.

The hope of charter-school supporters, as with other types of school-choice programs, is that offering more options to students will foster healthy competition and improve all public schools, charter and otherwise. Critics raise concerns about the level of quality at some charter schools, which are not subject to the same rigorous oversight as traditional public schools. In addition, as with aspects of school choice, many people fear that charter schools will drain much-needed funds from regular public schools, which still serve the vast majority of American students.

Corporations and schools

Beginning in the early 1990s, some troubled school districts have turned to outside help, hiring private companies to manage public schools. Most school districts are operated by school boards, which are composed of elected officials. In a few cases, corporations have taken over administrative duties, accepting as their fee the exact amount the school or district would receive from the government. Such companies assert that they can reduce expenses and streamline procedures so effectively that they can improve academic performance and upgrade school facilities while still making a profit. In 1992 the first of these companies, the Minnesota-based Education Alternatives Inc., or EAI, began operating an elementary school in Dade County, Florida. Soon after, EAI took over the administration of twelve public schools in Baltimore, Maryland, and then the entire district of Hartford, Connecticut.

EAI claimed that it saved money by eliminating waste and requiring contractors, from building maintenance companies to computer manufacturers, to compete for business. EAI also stated that it raised test scores and overall academic performance, though such claims were disputed by local school boards. Critics of EAI pointed out that the company had made cuts in special education and art and music programs. In School , Irene Dandridge, former president of the Baltimore Teachers Union, pointed out the basic problem with trying to run public schools for a profit: "There is just not enough money in public school education, particularly in urban centers, to have a profit and a good education, too." The school boards in Dade County, Baltimore, and Hartford all decided to terminate their relationship with EAI.

Aside from experiments with school management companies, many districts have initiated relationships with corporations as a way to boost school funding. As increasing emphasis is placed on standardized test scores, many schools have hired for-profit companies to assist in test preparation by tutoring students. A significant number of schools have accepted equipment from corporations in exchange for distributing certain materials to students. For example, a number of schools beginning in the early 1990s received free televisions, satellite dishes, and other media equipment from a company called Whittle Communications. In exchange, the schools had to broadcast twelve minutes per day of Channel One, a program consisting of ten minutes of news and two minutes of commercials. Numerous parents and educators objected to tax-supported public schools exposing students daily to commercials, many of which advertised products like gum, candy, and unhealthy snacks. Others suggested that such arrangements with corporations allow financially burdened school districts to acquire needed equipment that they otherwise could not afford.

Standardized testing

A fundamental part of the education reforms implemented in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries was a renewed emphasis on standardized testing as a way of measuring academic achievement. With standardized testing, all students in a given state, or, in some cases, the entire country, are given the exact same test, administered according to strict guidelines. Students had been taking standardized tests for many years, but such exams assumed a position of increasing importance during the 1990s.

In 2002 the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act, promoted and signed into law by President George W. Bush (1946–; served 2001–), took standardized testing to a new level. Among other provisions, NCLB mandated that each state had to immediately develop grade-appropriate standards for math and reading, with science standards to be developed soon after. To measure the extent to which students meet expectations in reading, math, and science, standardized tests developed by each state must be given to students every year from third grade through eighth grade. The results of the tests are made public, allowing parents to judge the effectiveness of each school in meeting its goals. Schools that fail, over a period of years, to make progress toward the state standards, are in jeopardy of losing funding from the federal government.

From its inception, NCLB has been a controversial law. Supporters describe it as sweeping legislation that finally makes schools responsible for helping every student reach academic goals. They also assert that NCLB gives states and local school districts more freedom to determine how federal funding is spent and gives parents more choices about where to send their children. A growing opposition movement, however, criticizes the increased focus on standardized tests. Proponents assert that such exams are not an accurate reflection of students' academic and intellectual development.

For the affected students, critics note, preparation for the annual standardized tests consumes a significant part of each school year. This means that teachers spend a great deal of time readying students for taking a test rather than exploring the most innovative, effective ways to help each individual learn. Many reformers have also expressed concern that standardized tests reflect a social and cultural bias toward white, middle-class students. In addition, the fact that each state can devise its own standards has raised the question of whether some states might deliberately make standardized tests easier to avoid the risk of losing funding.

Educational experts often disagree on the best methods of reforming the nation's school system, though most do agree that the system is in need of reform. For all of its flaws, however, the American public school system performs an extraordinary function. At the start of the twenty-first century, nearly 90 percent of the nation's children attended public schools. One hundred years earlier, that figure was closer to 50 percent, and most children only stayed in school for an average of five years. And yet, at that time, the public school system was viewed as one of the nation's greatest treasures, offering every child the chance to achieve the American dream.

The present-day American public school system may have disappointed millions of underprivileged and at-risk children. However, it still holds the potential for being an instrument of universal equality and excellence.

For More Information

Fisher, Leonard Everett. The Schools . New York: Holiday House, 1983.

Mondale, Sarah, and Sarah B. Patton, eds. School: The Story of American Public Education . Boston: Beacon Press, 2001.

Unger, Harlow G. Encyclopedia of American Education , 3 vols. New York: Facts on File, 1996.

"Guided Readings: The Struggle for Public Schools." Digital History . http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/subtitles.cfm?TitleID=23 (accessed on May 23, 2006).

"A Nation at Risk" (April 1983). U.S. Department of Education . http://www.ed.gov/pubs/NatAtRisk/risk.html (accessed on May 23, 2006).

National Center for Education Statistics. "High School Graduates Compared with Population 17 Years of Age, by Sex and Control of School: Selected Years, 1869–70 and 2004–05." Digest of Education Statistics, 2004 . http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d04/tables/dt04_102.asp (accessed on May 23, 2006).

"Overview of No Child Left Behind." Pennsylvania Department of Education . http://www.pde.state.pa.us/nclb/cwp/view.asp?a=3&Q=77815&nclbNav=%7C5483%7C (accessed on May 23, 2006).

Title IX . http://www.titleix.info/index.jsp (accessed on May 23, 2006).

Cite this article Pick a style below, and copy the text for your bibliography.

" The Education Reform Movement . " American Social Reform Movements Reference Library . . Encyclopedia.com. 18 Dec. 2024 < https://www.encyclopedia.com > .

"The Education Reform Movement ." American Social Reform Movements Reference Library . . Encyclopedia.com. (December 18, 2024). https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/education-reform-movement

"The Education Reform Movement ." American Social Reform Movements Reference Library . . Retrieved December 18, 2024 from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/education-reform-movement

Citation styles

Encyclopedia.com gives you the ability to cite reference entries and articles according to common styles from the Modern Language Association (MLA), The Chicago Manual of Style, and the American Psychological Association (APA).

Within the “Cite this article” tool, pick a style to see how all available information looks when formatted according to that style. Then, copy and paste the text into your bibliography or works cited list.

Because each style has its own formatting nuances that evolve over time and not all information is available for every reference entry or article, Encyclopedia.com cannot guarantee each citation it generates. Therefore, it’s best to use Encyclopedia.com citations as a starting point before checking the style against your school or publication’s requirements and the most-recent information available at these sites:

Modern Language Association

http://www.mla.org/style

The Chicago Manual of Style

http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html

American Psychological Association

http://apastyle.apa.org/

- Most online reference entries and articles do not have page numbers. Therefore, that information is unavailable for most Encyclopedia.com content. However, the date of retrieval is often important. Refer to each style’s convention regarding the best way to format page numbers and retrieval dates.

- In addition to the MLA, Chicago, and APA styles, your school, university, publication, or institution may have its own requirements for citations. Therefore, be sure to refer to those guidelines when editing your bibliography or works cited list.

More From encyclopedia.com

About this article, you might also like, nearby terms.

The Education Reform Movement: Transforming the Future

- July 7, 2023

Share This Article

Table of Contents

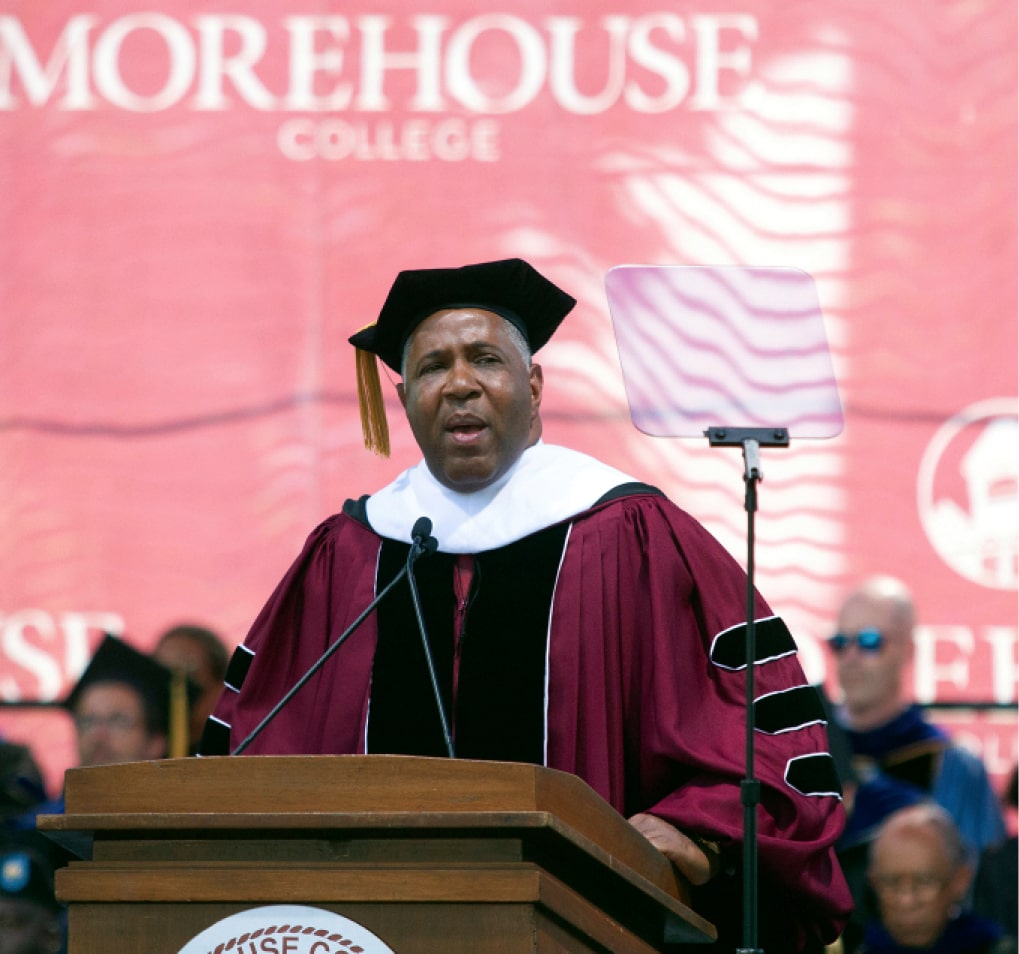

What is education reform, history of the education reform movement, the state of education reform in the u.s., why is education reform important, robert f. smith’s passion for education reform.

Key Takeaways:

- Education reform is an ongoing process to improve education by changing how the school or school system works.

- The education reform movement in the U.S. took off during the 1800s.

- Education reform is important because it helps ensure that education standards continually evolve for the better.

Education reform in the U.S. refers to efforts to improve the education system. States across the U.S. continually refine their requirements for education to ensure academic success. This approach to education is the result of the long-standing education reform movement that is alive and well today.

Below, we dig deep into what educational reform is and the history of the education reform movement. We will also discuss the current state of education reform in the U.S. and why education reform is essential.

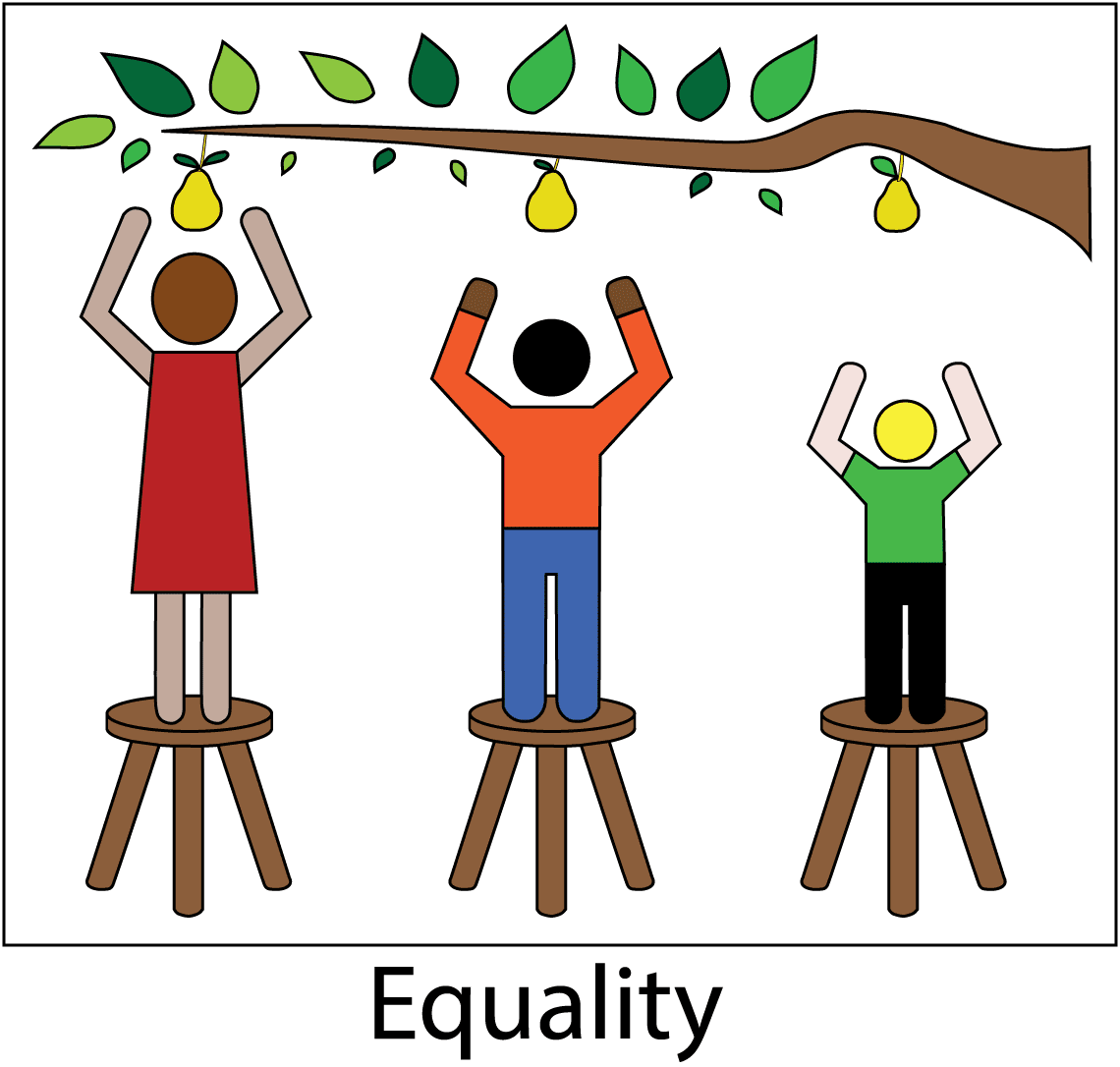

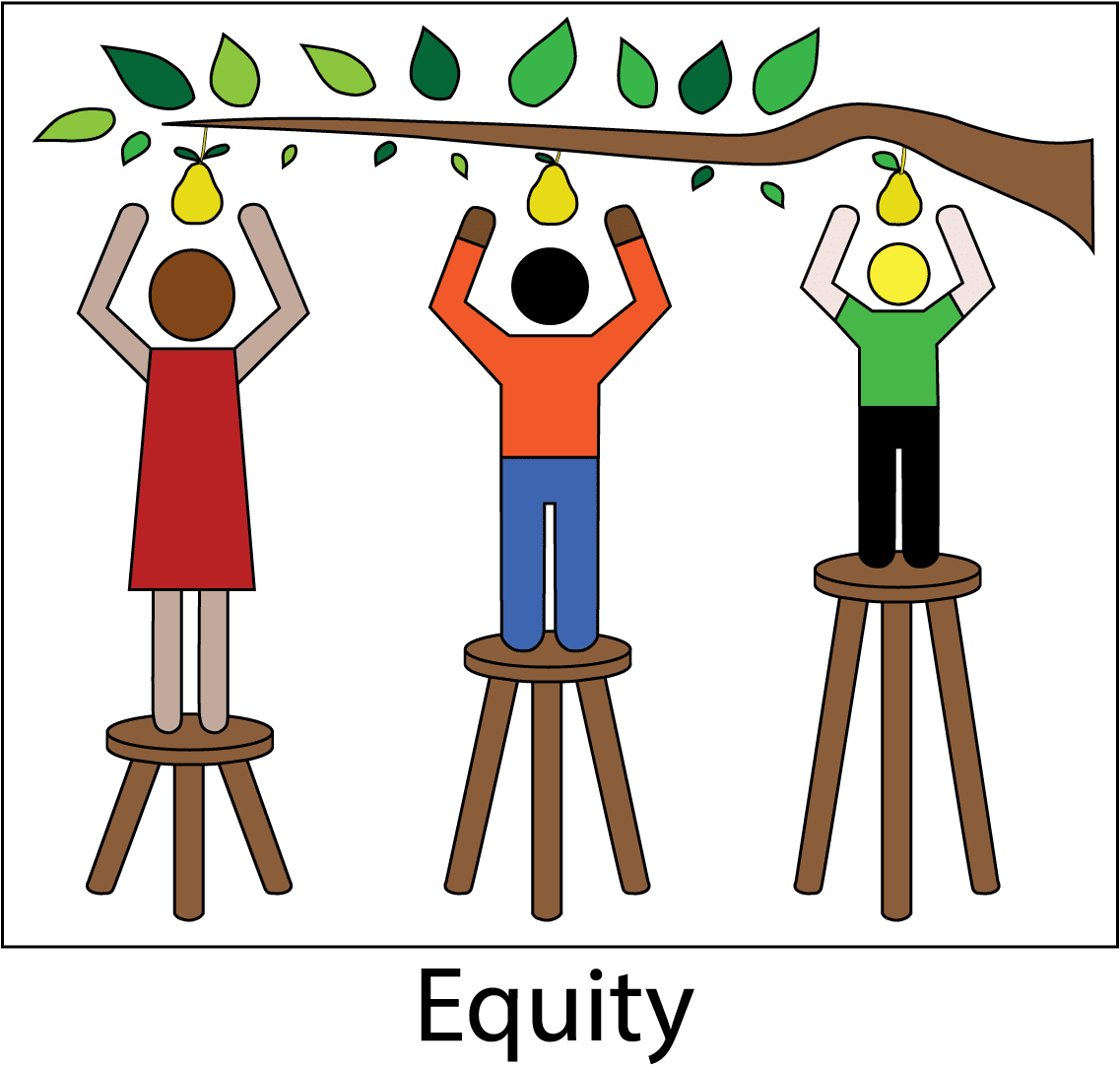

Education reform is an ongoing process to improve education by changing how the school or school system works. These changes, which typically happen through collaboration with various stakeholders, can include teaching methodologies or administrative practices. The goal of education reform is to create a quality education system that accommodates the needs of all students and meets the demands of an ever-changing society. More recently, education reformers have called for specific improvements, such as more funding, better teacher training, desegregation and smaller class sizes.

One notable example of education reform is former U.S. President George W. Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” program . The program, which was a new iteration of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, was introduced to make the U.S. education system more competitive. More specifically, the program aimed to make sure that schools work to boost the academic success of all students, especially those in special education and students from underrepresented communities. States were not mandated to implement these new requirements but risked losing federal funding if they did not.

Another example is former U.S. President Barack Obama’s “ Race to the Top ” initiative. The program continued to place an emphasis on testing but also offered incentives to states that were willing to implement changes in schools.

Education has been an integral aspect of the U.S.’s history. In the 17th century, prior to U.S. independence, New England Puritans insisted that each town create a school paid for by middle- and upper-class families. By the 18th century, Thomas Jefferson started promoting the idea that a democratic society needs educated residents. Some of the earliest education reformers used these ideas to create the foundation for the modern public education system. States in the north established some of the first tax-supported, tuition-free public schools.

The modern history of the education reform movement in the U.S. can be traced back to the 1800s, when increased demand for a skilled workforce sparked a need for basic education. With time, the progressive education movement evolved to focus more on a child-centered approach. This new approach emphasized the need for diversity and the development of critical, socially engaged intelligence. During the Civil Rights Movement, education reform evolved further to bring attention to the need for equal education. One of the most pivotal aspects of the movement was Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , a landmark Supreme Court case. In May 1954, the Supreme Court justices unanimously ruled that “separate-but-equal” (racial segregation) was unconstitutional.

In the last few decades, education reform placed more emphasis on the importance of standardized education. Since the education reform movement’s inception, it has shifted and split into different groups to accommodate society’s changing demands and challenges.

Get Industry leading insights from Robert F. Smith directly in your LinkedIn feed.

In recent years, education reform has been at the center of many debates. Opponents of recent reform measures say that initiatives spearheaded by leaders like former Presidents Bush and Obama did not lead to any marked improvement in educational outcomes. In particular, critics argue that things like the Common Core State Standards narrowed student curriculums. They maintain that these standards diminished art, music and social studies programs in schools nationwide.

Since 2016, education reform has focused on school choice and decreasing funding for public education. Currently, the education reform movement is centered around heated debates regarding content censorship in education in certain states and achievement gaps in education.

Education reform in the U.S. is important because a healthy education system is crucial to progress. Education helps society thrive and improves social mobility, economic growth and overall metrics of equity . Education reform also helps ensure that the education system adapts to the evolving needs of a rapidly changing society and economy. It is also critical because it helps to address and resolve important issues such as education inequities.

Philanthropist and entrepreneur Robert F. Smith , the son of two education professionals, learned the value of education at an early age. Throughout his career, Smith has become a steward for equity and education. For example, in 2021, Smith and software company PowerSchool each donated $1.25 million to complete teacher supply requests through DonorsChoose.

The donation helped to fulfill teacher requests at primarily Black schools in six Southern U.S. communities. At the time, education reform movements called for improving teachers’ ability to provide a quality education through supplies. Smith answered that call through a small and impactful way to improve the education system.

Follow Smith on LinkedIn to learn more about this and other topics.

Aspire to be someone who inspires?

Learn how to become a better leader from philanthropist Smith.

Follow Robert F. Smith on social media for the latest on his work as a business and philanthropic leader.

Priority Initiatives

Privacy Policy

Across our Communities

Mbe entrepreneurship & supplier diversity.

1. Provide technical expertise: offer subject matter and technical expertise to catalyze and support community initiatives

E.g., tax/accounting experts to help MBEs file taxes

E.g., business experts to help MBEs better access capital and craft business plans to scale their teams and operations

Access to Capital (CDFI/MDI)

2. Fund modernization & capacity-building and provide in-kind subject matter experts – $30M: help 4-5 CDFIs/MDIs over 5 years modernize their core systems, hire and train staff, expand marketing and standup SWAT team of experts to conduct needs diagnostic, implement tech solution & provide technical assistance

Systems and technology modernization – $10M-15M: Add/upgrade core banking systems, hardware and productivity tools, train frontline workforce on new systems & technology and hire engineering specialists to support customization and news systems rollout – over 5 years

Talent and workforce – $10M: hire and train additional frontline lending staff and invest in recruiting, training, compensation & benefits and retention to increase in-house expertise and loan capacity – over 5 years

Other capacity-building and outreach – $8M: hire additional staff to increase custom borrower and technical assistance (e.g., credit building, MBE financing options, etc.) and increase community outreach to drive regional awareness and new pipeline projects – over 5 years

Education/HBCU & Workforce Development

3. Offer more paid internships: signup onto InternX and offer 25+ additional paid internships per year to HBCU/Black students

Digital Access

4. Issue digital access equality bonds: issue equality progress bonds and invest proceeds into SCI’s digital access initiatives

5. Fund HBCU campus-wide internet – up to $50M in donations or in-kind: Partner with the Student Freedom Initiative to deliver campus-wide high-speed internet at ~10 HBCUs across SCI regions

6. Be an advocate for SCI priorities: engage federal and state agencies to drive policy and funding improvements to better support SCI’s near-term priorities

E.g., Engage the Small Business Administration and Minority Business Development Agency to increase technical assistance programs and annual spend to better support Minority Business Enterprises (MBEs) with capital and scaling needs