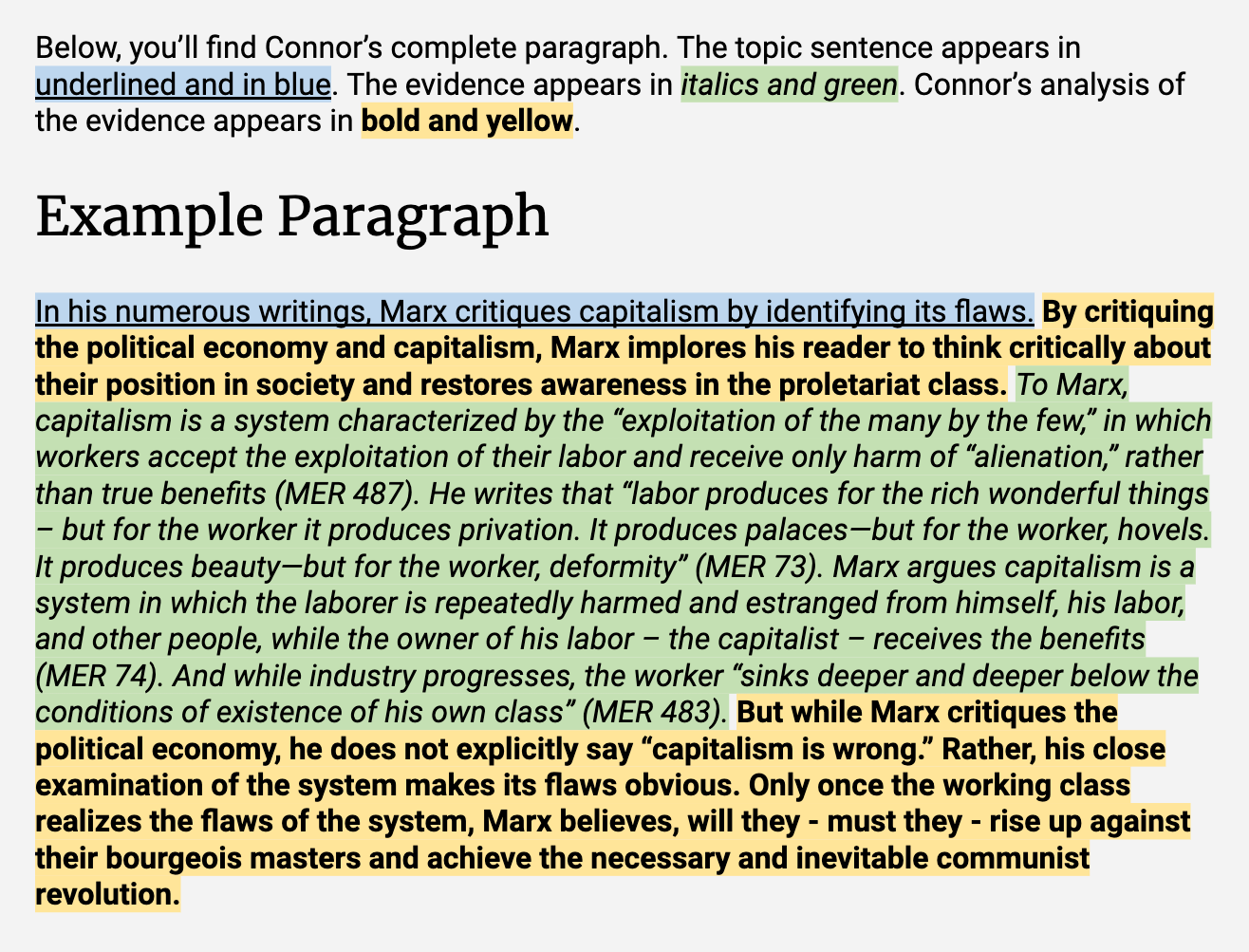

TOPIC SENTENCE/ In his numerous writings, Marx critiques capitalism by identifying its flaws. ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ By critiquing the political economy and capitalism, Marx implores his reader to think critically about their position in society and restores awareness in the proletariat class. EVIDENCE/ To Marx, capitalism is a system characterized by the “exploitation of the many by the few,” in which workers accept the exploitation of their labor and receive only harm of “alienation,” rather than true benefits ( MER 487). He writes that “labour produces for the rich wonderful things – but for the worker it produces privation. It produces palaces—but for the worker, hovels. It produces beauty—but for the worker, deformity” (MER 73). Marx argues capitalism is a system in which the laborer is repeatedly harmed and estranged from himself, his labor, and other people, while the owner of his labor – the capitalist – receives the benefits ( MER 74). And while industry progresses, the worker “sinks deeper and deeper below the conditions of existence of his own class” ( MER 483). ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ But while Marx critiques the political economy, he does not explicitly say “capitalism is wrong.” Rather, his close examination of the system makes its flaws obvious. Only once the working class realizes the flaws of the system, Marx believes, will they - must they - rise up against their bourgeois masters and achieve the necessary and inevitable communist revolution.

Not every paragraph will be structured exactly like this one, of course. But as you draft your own paragraphs, look for all three of these elements: topic sentence, evidence, and analysis.

- picture_as_pdf Anatomy Of a Body Paragraph

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Forums Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- English Grammar

- Writing Paragraphs

How to Structure Paragraphs in an Essay

Last Updated: February 28, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Danielle Blinka, MA, MPA . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 189,202 times.

Writing an essay can be challenging, especially if you're not sure how to structure your paragraphs. If you’re struggling to organize your essay, you’re in luck! Putting your paragraphs in order may become easier after you understand their purpose. Additionally, knowing what to include in your introduction, body, and conclusion paragraphs will help you more easily get your writing assignment finished.

Standard 5-Paragraph Essay Structure

A typical short essay has 5 paragraphs. Begin with a 1-paragraph introduction that gives an overview of the subject and introduces a specific topic or problem. Include at least 3 body paragraphs that support or explain your main point with evidence. End with a concluding paragraph that briefly summarizes your essay.

Essay Template and Sample Essay

Putting Your Paragraphs in Order

- A basic introduction will be about 3-4 sentences long.

- Body paragraphs will make up the bulk of your essay. At a minimum, a body paragraph needs to be 4 sentences long. However, a good body paragraph in a short essay will be at least 6-8 sentences long.

- A good conclusion for a short essay will be 3-4 sentences long.

- For example, let’s say you’re writing an essay about recycling. Your first point might be about the value of local recycling programs, while your second point might be about the importance of encouraging recycling at work or school. A good transition between these two points might be “furthermore” or “additionally.”

- If your third point is about how upcycling might be the best way to reuse old items, a good transition word might be “however” or “on the other hand.” This is because upcycling involves reusing items rather than recycling them, so it's a little bit different. You want your reader to recognize that you're talking about something that slightly contrasts with your original two points.

Structuring Your Introduction

- Provide a quote: “According to Neil LaBute, ‘We live in a disposable society.’”

- Include statistics: “The EPA reports that only 34 percent of waste created by Americans is recycled every year.”

- Give a rhetorical question: “If you could change your habits to save the planet, would you do it?”

- Here’s an example: “Recycling offers a way to reduce waste and reuse old items, but many people don’t bother recycling their old goods. Unless people change their ways, landfills will continue to grow as more generations discard their trash.”

- Here’s how a basic thesis about recycling might look: "To reduce the amount of trash in landfills, people must participate in local recycling programs, start recycling at school or work, and upcycle old items whenever they can."

- If you’re writing an argument or persuasive essay, your thesis might look like this: “Although recycling may take more effort, recycling and upcycling are both valuable ways to prevent expanding landfills.”

Crafting Good Body Paragraphs

- A good body paragraph in a short essay typically has 6-8 sentences. If you’re not sure how many sentences your paragraphs should include, talk to your instructor.

- Write a new paragraph for each of your main ideas. Packing too much information into one paragraph can make it confusing.

- If you begin your essay by writing an outline, include your topic sentence for each paragraph in your outline.

- You might write, “Local recycling programs are a valuable way to reduce waste, but only if people use them.”

- Your evidence might come from books, journal articles, websites, or other authoritative sources .

- The word evidence might make you think of data or experts. However, some essays will include only your ideas, depending on the assignment. In this case, you might be allowed to take evidence from your observations and experiences, but only if your assignment specifically allows this type of evidence.

- You could write, “According to Mayor Anderson’s office, only 23 percent of local households participate in the city’s recycling program.”

- In some cases, you may offer more than one piece of evidence in the same paragraph. Make sure you provide a 1 to 2 sentence explanation for each piece of evidence.

- For instance, “Residents who are using the recycling program aren’t contributing as much trash to local landfills, so they’re helping keep the community clean. On the other hand, most households don’t recycle, so the program isn’t as effective as it could be.”

- For instance, you could write, “Clearly, local recycling programs can make a big difference, but they aren’t the only way to reduce waste.”

Arranging Your Conclusion

- You could write, “By participating in local recycling programs, recycling at work, and upcycling old items, people can reduce their environmental footprint.”

- As an example, “Statistics show that few people are participating in available recycling programs, but they are an effective way to reduce waste. By recycling and upcycling, people can reduce their trash consumption by as much as 70%.”

- Give your readers a call to action. For example, “To save the planet, everyone needs to recycle."

- Offer a solution to the problem you presented. For instance, "With more education about recycling, more people will participate in their local programs."

- Point to the next question that needs to be answered. You might write, "To get more people to recycle, researchers need to determine the reasons why they don't."

- Provide a valuable insight about your topic. As an example, "If everyone recycled, landfills might become a thing of the past."

Community Q&A

- Ask a friend to read your essay and provide you with feedback. Ask if they understand your points and if any ideas need more development. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Writing gets easier with practice, so don’t give up! Everyone was a beginner at some point, and it’s normal to struggle with writing. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If you copy someone else’s writing or ideas, it’s called plagiarism. Don’t ever plagiarize, as this is a serious offense. Not only will you get in trouble if you plagiarize, you probably won’t receive credit for the assignment. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/introductions/

- ↑ https://www.student.unsw.edu.au/writing-your-essay

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/conclusions/

- ↑ https://www.plainlanguage.gov/guidelines/organize/use-transition-words/

- ↑ https://www.esu.edu/writing-studio/guides/hook.cfm

- ↑ https://wts.indiana.edu/writing-guides/how-to-write-a-thesis-statement.html

- ↑ https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/writing-paragraphs/structure

- ↑ https://lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/undergraduates/writing-guides/how-do-i-write-an-intro--conclusion----body-paragraph.html

- ↑ https://www.umgc.edu/current-students/learning-resources/writing-center/writing-resources/parts-of-an-essay/essay-conclusions

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jun 20, 2017

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

11 Rules for Essay Paragraph Structure (with Examples)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

How do you structure a paragraph in an essay?

If you’re like the majority of my students, you might be getting your basic essay paragraph structure wrong and getting lower grades than you could!

In this article, I outline the 11 key steps to writing a perfect paragraph. But, this isn’t your normal ‘how to write an essay’ article. Rather, I’ll try to give you some insight into exactly what teachers look out for when they’re grading essays and figuring out what grade to give them.

You can navigate each issue below, or scroll down to read them all:

1. Paragraphs must be at least four sentences long 2. But, at most seven sentences long 3. Your paragraph must be Left-Aligned 4. You need a topic sentence 5 . Next, you need an explanation sentence 6. You need to include an example 7. You need to include citations 8. All paragraphs need to be relevant to the marking criteria 9. Only include one key idea per paragraph 10. Keep sentences short 11. Keep quotes short

Paragraph structure is one of the most important elements of getting essay writing right .

As I cover in my Ultimate Guide to Writing an Essay Plan , paragraphs are the heart and soul of your essay.

However, I find most of my students have either:

- forgotten how to write paragraphs properly,

- gotten lazy, or

- never learned it in the first place!

Paragraphs in essay writing are different from paragraphs in other written genres .

In fact, the paragraphs that you are reading now would not help your grades in an essay.

That’s because I’m writing in journalistic style, where paragraph conventions are vastly different.

For those of you coming from journalism or creative writing, you might find you need to re-learn paragraph writing if you want to write well-structured essay paragraphs to get top grades.

Below are eleven reasons your paragraphs are losing marks, and what to do about it!

Essay Paragraph Structure Rules

1. your paragraphs must be at least 4 sentences long.

In journalism and blog writing, a one-sentence paragraph is great. It’s short, to-the-point, and helps guide your reader. For essay paragraph structure, one-sentence paragraphs suck.

A one-sentence essay paragraph sends an instant signal to your teacher that you don’t have much to say on an issue.

A short paragraph signifies that you know something – but not much about it. A one-sentence paragraph lacks detail, depth and insight.

Many students come to me and ask, “what does ‘add depth’ mean?” It’s one of the most common pieces of feedback you’ll see written on the margins of your essay.

Personally, I think ‘add depth’ is bad feedback because it’s a short and vague comment. But, here’s what it means: You’ve not explained your point enough!

If you’re writing one-, two- or three-sentence essay paragraphs, you’re costing yourself marks.

Always aim for at least four sentences per paragraph in your essays.

This doesn’t mean that you should add ‘fluff’ or ‘padding’ sentences.

Make sure you don’t:

a) repeat what you said in different words, or b) write something just because you need another sentence in there.

But, you need to do some research and find something insightful to add to that two-sentence paragraph if you want to ace your essay.

Check out Points 5 and 6 for some advice on what to add to that short paragraph to add ‘depth’ to your paragraph and start moving to the top of the class.

- How to Make an Essay Longer

- How to Make an Essay Shorter

2. Your Paragraphs must not be more than 7 Sentences Long

Okay, so I just told you to aim for at least four sentences per paragraph. So, what’s the longest your paragraph should be?

Seven sentences. That’s a maximum.

So, here’s the rule:

Between four and seven sentences is the sweet spot that you need to aim for in every single paragraph.

Here’s why your paragraphs shouldn’t be longer than seven sentences:

1. It shows you can organize your thoughts. You need to show your teacher that you’ve broken up your key ideas into manageable segments of text (see point 10)

2. It makes your work easier to read. You need your writing to be easily readable to make it easy for your teacher to give you good grades. Make your essay easy to read and you’ll get higher marks every time.

One of the most important ways you can make your work easier to read is by writing paragraphs that are less than six sentences long.

3. It prevents teacher frustration. Teachers are just like you. When they see a big block of text their eyes glaze over. They get frustrated, lost, their mind wanders … and you lose marks.

To prevent teacher frustration, you need to ensure there’s plenty of white space in your essay. It’s about showing them that the piece is clearly structured into one key idea per ‘chunk’ of text.

Often, you might find that your writing contains tautologies and other turns of phrase that can be shortened for clarity.

3. Your Paragraph must be Left-Aligned

Turn off ‘Justified’ text and: Never. Turn. It. On. Again.

Justified text is where the words are stretched out to make the paragraph look like a square. It turns the writing into a block. Don’t do it. You will lose marks, I promise you! Win the psychological game with your teacher: left-align your text.

A good essay paragraph is never ‘justified’.

I’m going to repeat this, because it’s important: to prevent your essay from looking like a big block of muddy, hard-to-read text align your text to the left margin only.

You want white space on your page – and lots of it. White space helps your reader scan through your work. It also prevents it from looking like big blocks of text.

You want your reader reading vertically as much as possible: scanning, browsing, and quickly looking through for evidence you’ve engaged with the big ideas.

The justified text doesn’t help you do that. Justified text makes your writing look like a big, lumpy block of text that your reader doesn’t want to read.

What’s wrong with Center-Aligned Text?

While I’m at it, never, ever, center-align your text either. Center-aligned text is impossible to skim-read. Your teacher wants to be able to quickly scan down the left margin to get the headline information in your paragraph.

Not many people center-align text, but it’s worth repeating: never, ever center-align your essays.

Don’t annoy your reader. Left align your text.

4. Your paragraphs must have a Topic Sentence

The first sentence of an essay paragraph is called the topic sentence. This is one of the most important sentences in the correct essay paragraph structure style.

The topic sentence should convey exactly what key idea you’re going to cover in your paragraph.

Too often, students don’t let their reader know what the key idea of the paragraph is until several sentences in.

You must show what the paragraph is about in the first sentence.

You never, ever want to keep your reader in suspense. Essays are not like creative writing. Tell them straight away what the paragraph is about. In fact, if you can, do it in the first half of the first sentence .

I’ll remind you again: make it easy to grade your work. Your teacher is reading through your work trying to determine what grade to give you. They’re probably going to mark 20 assignments in one sitting. They have no interest in storytelling or creativity. They just want to know how much you know! State what the paragraph is about immediately and move on.

Suggested: Best Words to Start a Paragraph

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: Writing a Topic Sentence If your paragraph is about how climate change is endangering polar bears, say it immediately : “Climate change is endangering polar bears.” should be your first sentence in your paragraph. Take a look at first sentence of each of the four paragraphs above this one. You can see from the first sentence of each paragraph that the paragraphs discuss:

When editing your work, read each paragraph and try to distil what the one key idea is in your paragraph. Ensure that this key idea is mentioned in the first sentence .

(Note: if there’s more than one key idea in the paragraph, you may have a problem. See Point 9 below .)

The topic sentence is the most important sentence for getting your essay paragraph structure right. So, get your topic sentences right and you’re on the right track to a good essay paragraph.

5. You need an Explanation Sentence

All topic sentences need a follow-up explanation. The very first point on this page was that too often students write paragraphs that are too short. To add what is called ‘depth’ to a paragraph, you can come up with two types of follow-up sentences: explanations and examples.

Let’s take explanation sentences first.

Explanation sentences give additional detail. They often provide one of the following services:

Let’s go back to our example of a paragraph on Climate change endangering polar bears. If your topic sentence is “Climate change is endangering polar bears.”, then your follow-up explanation sentence is likely to explain how, why, where, or when. You could say:

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: Writing Explanation Sentences 1. How: “The warming atmosphere is melting the polar ice caps.” 2. Why: “The polar bears’ habitats are shrinking every single year.” 3. Where: “This is happening in the Antarctic ice caps near Greenland.” 4. When: “Scientists first noticed the ice caps were shrinking in 1978.”

You don’t have to provide all four of these options each time.

But, if you’re struggling to think of what to add to your paragraph to add depth, consider one of these four options for a good quality explanation sentence.

>>>RELATED ARTICLE: SHOULD YOU USE RHETORICAL QUESTIONS IN ESSAYS ?

6. Your need to Include an Example

Examples matter! They add detail. They also help to show that you genuinely understand the issue. They show that you don’t just understand a concept in the abstract; you also understand how things work in real life.

Example sentences have the added benefit of personalising an issue. For example, after saying “Polar bears’ habitats are shrinking”, you could note specific habitats, facts and figures, or even a specific story about a bear who was impacted.

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: Writing an ‘Example’ Sentence “For example, 770,000 square miles of Arctic Sea Ice has melted in the past four decades, leading Polar Bear populations to dwindle ( National Geographic, 2018 )

In fact, one of the most effective politicians of our times – Barrack Obama – was an expert at this technique. He would often provide examples of people who got sick because they didn’t have healthcare to sell Obamacare.

What effect did this have? It showed the real-world impact of his ideas. It humanised him, and got him elected president – twice!

Be like Obama. Provide examples. Often.

7. All Paragraphs need Citations

Provide a reference to an academic source in every single body paragraph in the essay. The only two paragraphs where you don’t need a reference is the introduction and conclusion .

Let me repeat: Paragraphs need at least one reference to a quality scholarly source .

Let me go even further:

Students who get the best marks provide two references to two different academic sources in every paragraph.

Two references in a paragraph show you’ve read widely, cross-checked your sources, and given the paragraph real thought.

It’s really important that these references link to academic sources, not random websites, blogs or YouTube videos. Check out our Seven Best types of Sources to Cite in Essays post to get advice on what sources to cite. Number 6 w ill surprise you!

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: In-Text Referencing in Paragraphs Usually, in-text referencing takes the format: (Author, YEAR), but check your school’s referencing formatting requirements carefully. The ‘Author’ section is the author’s last name only. Not their initials. Not their first name. Just their last name . My name is Chris Drew. First name Chris, last name Drew. If you were going to reference an academic article I wrote in 2019, you would reference it like this: (Drew, 2019).

Where do you place those two references?

Place the first reference at the end of the first half of the paragraph. Place the second reference at the end of the second half of the paragraph.

This spreads the references out and makes it look like all the points throughout the paragraph are backed up by your sources. The goal is to make it look like you’ve reference regularly when your teacher scans through your work.

Remember, teachers can look out for signposts that indicate you’ve followed academic conventions and mentioned the right key ideas.

Spreading your referencing through the paragraph helps to make it look like you’ve followed the academic convention of referencing sources regularly.

Here are some examples of how to reference twice in a paragraph:

- If your paragraph was six sentences long, you would place your first reference at the end of the third sentence and your second reference at the end of the sixth sentence.

- If your paragraph was five sentences long, I would recommend placing one at the end of the second sentence and one at the end of the fifth sentence.

You’ve just read one of the key secrets to winning top marks.

8. Every Paragraph must be relevant to the Marking Criteria

Every paragraph must win you marks. When you’re editing your work, check through the piece to see if every paragraph is relevant to the marking criteria.

For the British: In the British university system (I’m including Australia and New Zealand here – I’ve taught at universities in all three countries), you’ll usually have a ‘marking criteria’. It’s usually a list of between two and six key learning outcomes your teacher needs to use to come up with your score. Sometimes it’s called a:

- Marking criteria

- Marking rubric

- (Key) learning outcome

- Indicative content

Check your assignment guidance to see if this is present. If so, use this list of learning outcomes to guide what you write. If your paragraphs are irrelevant to these key points, delete the paragraph .

Paragraphs that don’t link to the marking criteria are pointless. They won’t win you marks.

For the Americans: If you don’t have a marking criteria / rubric / outcomes list, you’ll need to stick closely to the essay question or topic. This goes out to those of you in the North American system. North America (including USA and Canada here) is often less structured and the professor might just give you a topic to base your essay on.

If all you’ve got is the essay question / topic, go through each paragraph and make sure each paragraph is relevant to the topic.

For example, if your essay question / topic is on “The Effects of Climate Change on Polar Bears”,

- Don’t talk about anything that doesn’t have some connection to climate change and polar bears;

- Don’t talk about the environmental impact of oil spills in the Gulf of Carpentaria;

- Don’t talk about black bear habitats in British Columbia.

- Do talk about the effects of climate change on polar bears (and relevant related topics) in every single paragraph .

You may think ‘stay relevant’ is obvious advice, but at least 20% of all essays I mark go off on tangents and waste words.

Stay on topic in Every. Single. Paragraph. If you want to learn more about how to stay on topic, check out our essay planning guide .

9. Only have one Key Idea per Paragraph

One key idea for each paragraph. One key idea for each paragraph. One key idea for each paragraph.

Don’t forget!

Too often, a student starts a paragraph talking about one thing and ends it talking about something totally different. Don’t be that student.

To ensure you’re focussing on one key idea in your paragraph, make sure you know what that key idea is. It should be mentioned in your topic sentence (see Point 3 ). Every other sentence in the paragraph adds depth to that one key idea.

If you’ve got sentences in your paragraph that are not relevant to the key idea in the paragraph, they don’t fit. They belong in another paragraph.

Go through all your paragraphs when editing your work and check to see if you’ve veered away from your paragraph’s key idea. If so, you might have two or even three key ideas in the one paragraph.

You’re going to have to get those additional key ideas, rip them out, and give them paragraphs of their own.

If you have more than one key idea in a paragraph you will lose marks. I promise you that.

The paragraphs will be too hard to read, your reader will get bogged down reading rather than scanning, and you’ll have lost grades.

10. Keep Sentences Short

If a sentence is too long it gets confusing. When the sentence is confusing, your reader will stop reading your work. They will stop reading the paragraph and move to the next one. They’ll have given up on your paragraph.

Short, snappy sentences are best.

Shorter sentences are easier to read and they make more sense. Too often, students think they have to use big, long, academic words to get the best marks. Wrong. Aim for clarity in every sentence in the paragraph. Your teacher will thank you for it.

The students who get the best marks write clear, short sentences.

When editing your draft, go through your essay and see if you can shorten your longest five sentences.

(To learn more about how to write the best quality sentences, see our page on Seven ways to Write Amazing Sentences .)

11. Keep Quotes Short

Eighty percent of university teachers hate quotes. That’s not an official figure. It’s my guestimate based on my many interactions in faculty lounges. Twenty percent don’t mind them, but chances are your teacher is one of the eight out of ten who hate quotes.

Teachers tend to be turned off by quotes because it makes it look like you don’t know how to say something on your own words.

Now that I’ve warned you, here’s how to use quotes properly:

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: How To Use Quotes in University-Level Essay Paragraphs 1. Your quote should be less than one sentence long. 2. Your quote should be less than one sentence long. 3. You should never start a sentence with a quote. 4. You should never end a paragraph with a quote. 5 . You should never use more than five quotes per essay. 6. Your quote should never be longer than one line in a paragraph.

The minute your teacher sees that your quote takes up a large chunk of your paragraph, you’ll have lost marks.

Your teacher will circle the quote, write a snarky comment in the margin, and not even bother to give you points for the key idea in the paragraph.

Avoid quotes, but if you really want to use them, follow those five rules above.

I’ve also provided additional pages outlining Seven tips on how to use Quotes if you want to delve deeper into how, when and where to use quotes in essays. Be warned: quoting in essays is harder than you thought.

Follow the advice above and you’ll be well on your way to getting top marks at university.

Writing essay paragraphs that are well structured takes time and practice. Don’t be too hard on yourself and keep on trying!

Below is a summary of our 11 key mistakes for structuring essay paragraphs and tips on how to avoid them.

I’ve also provided an easy-to-share infographic below that you can share on your favorite social networking site. Please share it if this article has helped you out!

11 Biggest Essay Paragraph Structure Mistakes you’re probably Making

1. Your paragraphs are too short 2. Your paragraphs are too long 3. Your paragraph alignment is ‘Justified’ 4. Your paragraphs are missing a topic sentence 5 . Your paragraphs are missing an explanation sentence 6. Your paragraphs are missing an example 7. Your paragraphs are missing references 8. Your paragraphs are not relevant to the marking criteria 9. You’re trying to fit too many ideas into the one paragraph 10. Your sentences are too long 11. Your quotes are too long

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

4 thoughts on “11 Rules for Essay Paragraph Structure (with Examples)”

Hello there. I noticed that throughout this article on Essay Writing, you keep on saying that the teacher won’t have time to go through the entire essay. Don’t you think this is a bit discouraging that with all the hard work and time put into your writing, to know that the teacher will not read through the entire paper?

Hi Clarence,

Thanks so much for your comment! I love to hear from readers on their thoughts.

Yes, I agree that it’s incredibly disheartening.

But, I also think students would appreciate hearing the truth.

Behind closed doors many / most university teachers are very open about the fact they ‘only have time to skim-read papers’. They regularly bring this up during heated faculty meetings about contract negotiations! I.e. in one university I worked at, we were allocated 45 minutes per 10,000 words – that’s just over 4 minutes per 1,000 word essay, and that’d include writing the feedback, too!

If students know the truth, they can better write their essays in a way that will get across the key points even from a ‘skim-read’.

I hope to write candidly on this website – i.e. some of this info will never be written on university blogs because universities want to hide these unfortunate truths from students.

Thanks so much for stopping by!

Regards, Chris

This is wonderful and helpful, all I say is thank you very much. Because I learned a lot from this site, own by chris thank you Sir.

Thank you. This helped a lot.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The most obvious is to spend one paragraph discussing the similarities between the topics you’re covering (comparing), then one paragraph detailing their differences (contrasting), followed by a paragraph that explores whether they’re more alike or more different from each other.

The five-paragraph essay structure consists of, in order: one introductory paragraph that introduces the main topic and states a thesis, three body paragraphs to support the thesis, and one concluding paragraph to wrap up the points made in the essay.

The number of paragraphs in your essay should be determined by the number of steps you need to take to build your argument. To write strong paragraphs, try to focus each paragraph on one main point—and begin a new paragraph when you are moving to a new point or example.

The chronological approach (sometimes called the cause-and-effect approach) is probably the simplest way to structure an essay. It just means discussing events in the order in which they occurred, discussing how they are related (i.e. the cause and effect involved) as you go.

A typical short essay has 5 paragraphs. Begin with a 1-paragraph introduction that gives an overview of the subject and introduces a specific topic or problem. Include at least 3 body paragraphs that support or explain your main point with evidence. End with a concluding paragraph that briefly summarizes your essay.

What are the 5 parts of an essay? Explore how the introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion parts of an essay work together.

1. Paragraphs must be at least four sentences long. 2. But, at most seven sentences long. 3. Your paragraph must be Left-Aligned. 4. You need a topic sentence. 5 . Next, you need an explanation sentence. 6. You need to include an example. 7. You need to include citations. 8. All paragraphs need to be relevant to the marking criteria. 9.

Guide to Writing a Body Paragraph. Body paragraphs are the parts where you present your evidence and make arguments, which one may argue makes them the most important part of any essay. In this guide, you will learn how to write clear, effective, and convincing body paragraphs in an academic essay.

The number, length and order of your paragraphs will depend on what you’re writing—but each paragraph must be: Unified : all the sentences relate to one central point or idea. Coherent : the sentences are logically organized and clearly connected.

Essay introduction – Example 1 . Here is an example of an introduction to an essay that provides: . Background information. Some background information is provided to give the reader some context for the discussion. Purpose. It is clearly stated what the essay will argue – and is a direct response to the essay question. Outline.